![Femme d’un peintre [Helene Abelen], vers 1926 © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur - August Sander Archiv, Cologne; ADAGP, Paris, 2015.](../../../wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Sander003.jpg)

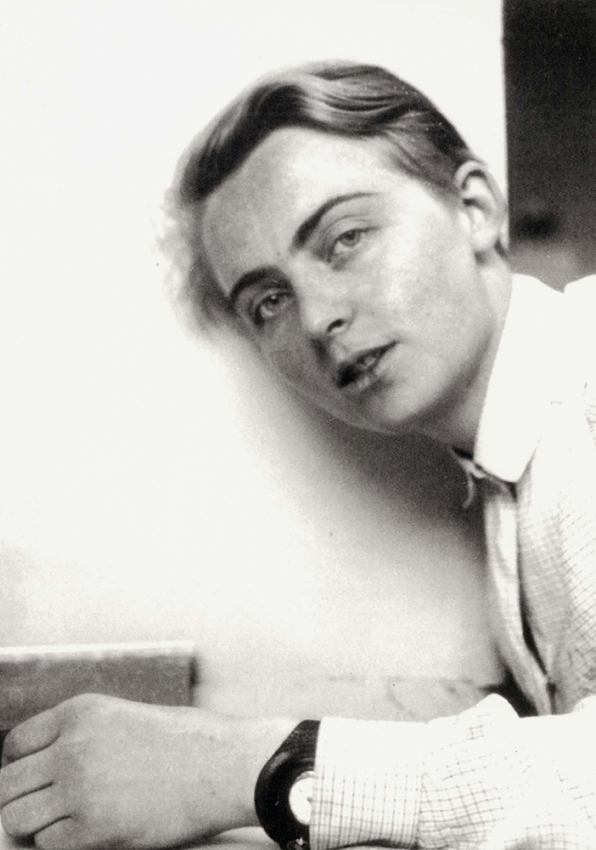

August Sander, Painter’s Wife [Helene Abelen], circa 1926 © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; ADAGP, Paris, 2015.

Two of the many compelling photographs of the so-called “New Woman” of the interwar period were not made by a woman photographer – although this is the subject of my essay – but by the great visual encyclopedist of (German) modernity, August Sander. One doesn’t know the identity of the woman described as “Secretary at Western German Radio in Cologne” (1931), but Helene Abelen was the young wife of the Cologne painter Peter Abelen who commissioned the portrait (1926). Together, the two portraits are almost stereotypical incarnations of the Nouvelle Femme or Neue Frau, or, as she was also known, the “Modern Woman”. A partly mythic, partly sociological, partly demographic figure that emerged as early as the 1880s, she was a locus of anxieties and fantasies, a target for advertisers and the entertainment industry, a chip in national political debates, a perceived threat to working men’s interests, the scourge of pro-natalists, the symbol of immorality and sexual license, and inseparable from what Rita Felski has characterized as “the contradictory and conflictual impulses shaping the logic – or rather logics—of modern development” 1.

But as Katharina von Ankum observes, the German version of the New Woman was as fleeting at it was ambiguous and generational: “Despite limited reality, the icon of the New Woman that emerged from the war years as the embodiment of the sexually liberated, economically independent self-reliant female was perceived as a threat to social stability and an impediment to Germany’s political and economic reconstruction. The discursive obsession with female identity was prompted by the sexualization of the public sphere resulting from the entry of large numbers of women into the modern workplace, the perception of a “birth-strike” among middle-class women and the decisively masculine appearance of the New Woman that repressed the physical markers of femininity.” 2

If Sander’s women seem immediately recognizable as symbols of this new feminine identity, as with all photographs, we need to be cautious about taking appearance for reality. Thus, the androgynous “look” of Helene Abelen might suggest one kind of identity, but another portrait by Sander of Abelen and her daughter, Josepha, suggests quite another. The very short hair, cigarette, embroidered silk dress and unflinching expression of the secretary give little clue to what might well have been her material circumstances.

As Attina Grossman memorably described her, “The New Woman was not only the intellectual with a Marlene Dietrich-style suit and short mannish haircut, or the young white-collar worker in a flapper outfit. She was also the young married factory worker who cooked only one warm meal a day, cut her hair short into a practical Bubikopf, and tried with all available means to keep her family small.” 3 And as Grossman further demonstrated with respect to German women, sexual politics, including contraception, abortion, non-monogamous, same sex or bi-sexual relationships – all were complexly braided in the collective imaginaire no less than in the lives and experiences of real woman. This was equally the case in France, where Victor Margueritte’s sensational and bestselling novel of 1922 did much to create the mythologies of his eponymous “Garçonne”, or in England, as well as well as France, where many considered the struggles for the suffrage, feminism and lesbianism to be part of a shared continuum 4. “The civilization has no more sexes”, lamented Pierre Drieu La Rochelle in 1922 5. Needless to say, the myth and the realities of the new woman need to be clearly separated, nation by nation, class by class, and there exists a vast literature on the subject that does precisely that 6.

It is a cliché in photography history to note that the remarkable generation of German and Eastern European women photographers active in the interwar period are collective exemplars of the New Woman. In this regard, the increasing interest in the lives and work of women photographers, evident perhaps in the overlap of Krull’s monographic exhibition at the Jeu de Paume and the Musée d’Orsay’s “Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?” provide an occasion to reflect on a range of more general issues. As Helen Trompeteler observes apropos of Lucia Moholy, “The story of Moholy and her contemporaries including Marianne Brandt, Marianne Breslauer and Florence Henri is one of modern photography, but also one of the ‘New Woman’, as reflected in the many explorations of female identity in photography from this period, especially through self-portraiture.” 7 One could easily add another twenty or thirty names, although until recently, most of them were absent from standard photographic histories 8. In this regard, the increasing interest in the lives and work of women photographers, evident perhaps in the overlap of Krull’s monographic exhibition at the Jeu de Paume (2 June – 27 September 2015) and the Musée d’Orsay’s Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? (13 October 2015 – 24 January 2016) provides an occasion to reflect on a range of more general issues. Moreover, the Jeu de Paume’s important series of monographic exhibitions featuring women photographers active in both the pre- and interwar years has done much to recover the lives and work of women who, as much as their male contemporaries, contributed to and even expanded the visual culture of modernism. 9

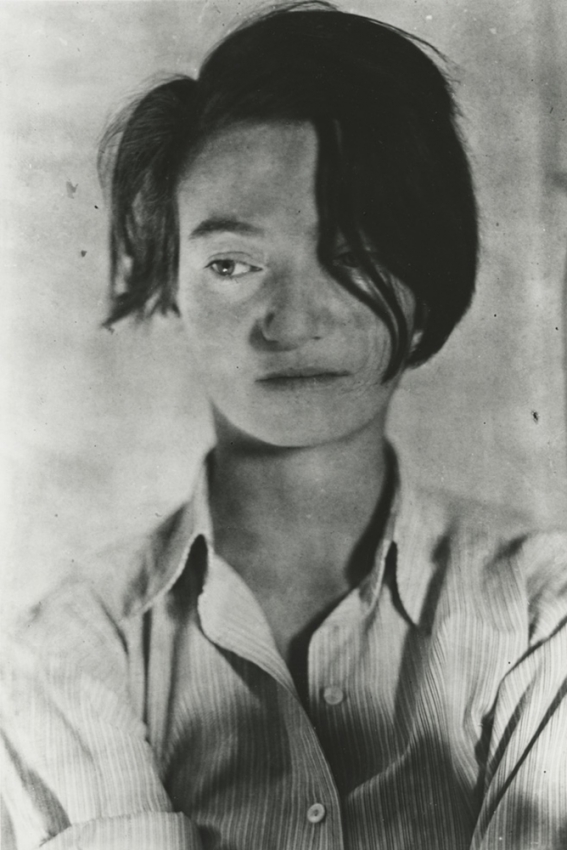

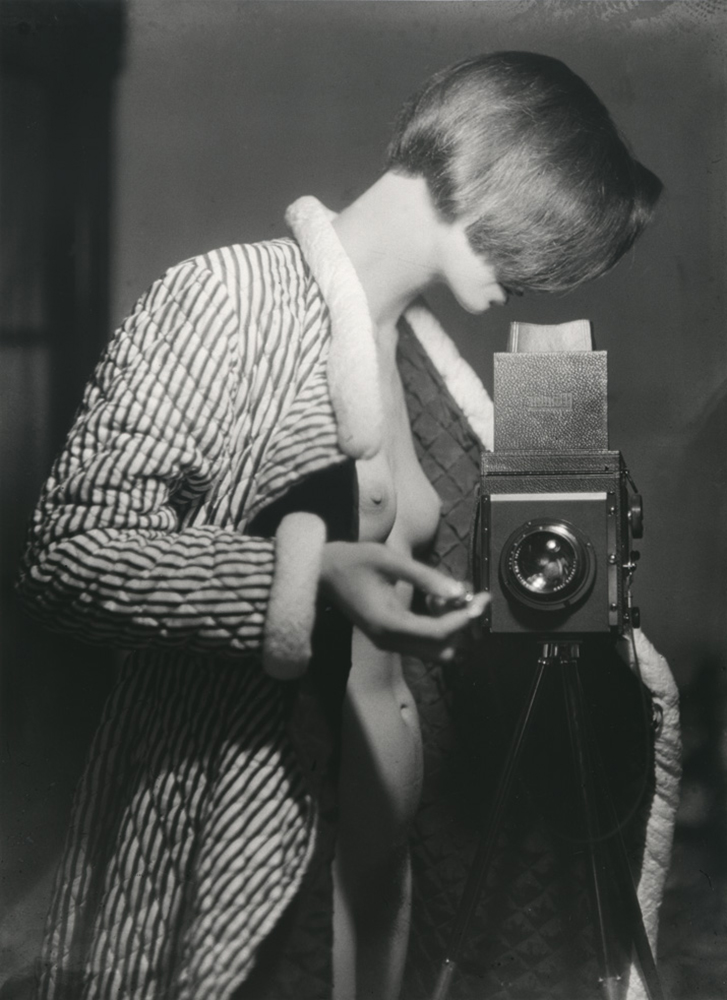

Marianne Breslauer, Die Fotografin [La Photographe], 1933 © Marianne Breslauer / Fotostiftung Schweiz

It should be noted, however, that the period in which women photographers such as Krull and Henri established their careers and reputations is an exceptional one in photographic history, one that might well be called the second “invention” of photography. Characterized by an expanded field of applications, new or improved technologies of reproduction, lighter cameras, faster films, various avant-garde formations, and an explosive growth of all mass media, including advertising, working photographers were no longer necessarily dependent on studio portraiture to earn a living 10. Many of the most well-known women photographers of the period produced work for advertising, fashion, and the picture press, which itself included mass-market and more avant-gardist publications. This makes it exceptionally difficult to take any given corpus of photographic production as an “œuvre” inasmuch as no one could have earned a living outside of commercial or editorial sources 11. And since even artists like Moholy-Nagy saw no contradiction in producing advertisements for clients, “new vision” photography, its styles and syntax came to be considered merely as a signifier for “the modern.” As indeed, was the “new woman” herself. Moreover, as the medium was increasingly conscripted by artists associated with a diverse array of artistic formations and agendas (e.g., constructivism, surrealism, the Bauhaus) it became further legitimized as a medium for creative expression. Influential exhibitions such as the 1928 “Neue Wege der Photographie” in Jena, the Stuttgart “Film und Foto”, in 1929, “Das Lichtbild” in Munich in 1930, “Fotographie der Gegenwart” in Essen in 1929 and its Dusseldorf successor in 1936, were accompanied by publications such as Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei, Fotographie, Film (1924), Werner’s Graeff’s Es Kommt der neue Fotograph (1929), and Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschishold’s 1930 Auge/Oeil (Photo/Photo Eye) 12 in 1930. Altogether, these further disseminated the techno-utopianism and innovative stylistic approaches of modernist photography, as well as the picture press and advertising. And because this period coincided with the near centennial of photography’s invention (1939), there appeared numerous critical, philosophical and historical accounts of the medium and its socio-cultural and indeed political ramifications. 13

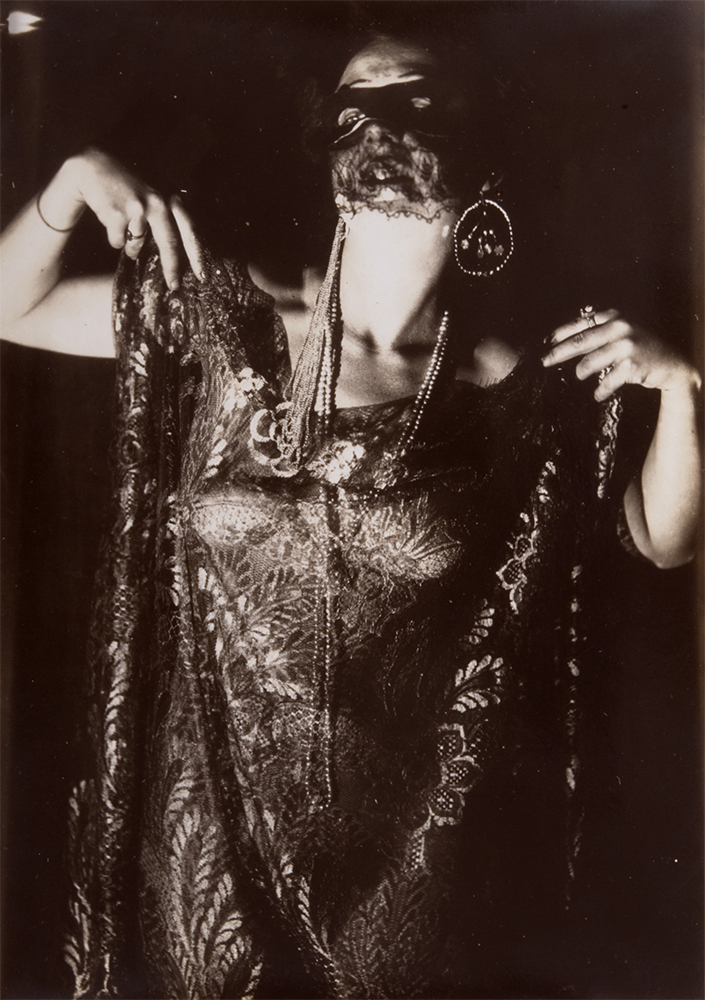

Germaine Krull — Advertisement design for Paul Poiret, 1926. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Georges Meguerditchian

For women photographers, however, increased opportunities were the fruit of forty years of [uneven] progress in legal, educational, vocational, professional and not least, economic emancipation. These varied greatly from country to country; uneven development is graphically illustrated by enfranchisement itself. Women gained the vote in Finland in 1906; in the Weimar Republic in 1919, in the U.S. in 1922, and France, in 1944 (although they could vote only in the 1946 elections). Such reforms that did occur, beginning in the fin-de-siècle, increased women’s presence in the labor force, but it was the war itself, initially with its large-scale mobilization and its eventual slaughter of millions, that necessitated women’s labor, even in formerly masculine occupations. In Germany and a few other Eastern and Nordic countries, women had access to a few photography schools even in the prewar period. (Krull, for example, had attended the Lehr-und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, a professional school in Munich that had admitted women as early as 1906). As Ute Eskildsen noted, aside from those who served apprenticeships in photographic studios or attended photography schools (Munich, Leipzig, Berlin), women photographers had either a crafts-based training, were self-taught, or became interested in photography while studying art 14.

But it was the war itself that altered woman’s real, material and imaginary status and volatilized the collision of national traumas, a crisis of patriarchal authority, and the loss of a generation of young men. Thus, the first and most obvious point to make is that the interwar period in Europe favored (rather than simply permitted or tolerated) the emergence of women photographers and other professionally active women until the rise of fascism and the advent of the Second World War reversed their fortunes, making many of them refugees or immigrants and basically ending the reciprocally energizing forces of modernism, new media, and new women.

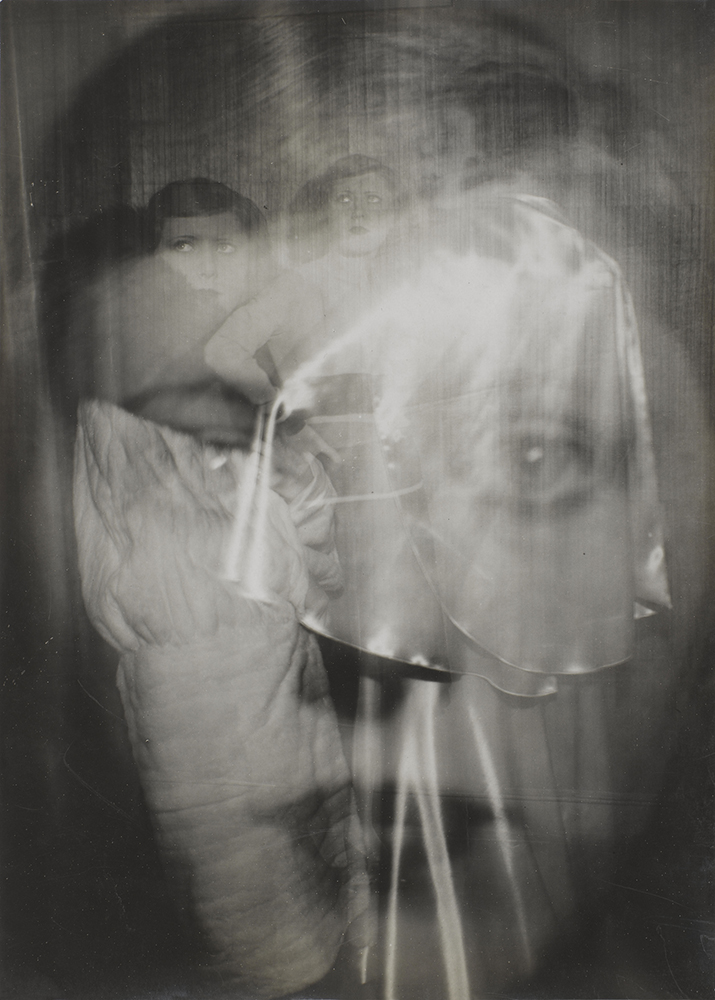

Gertrud Arndt, Autoportrait dans l’atelier, Bauhaus Dessau, c.1926 © Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin / ADAGP, Paris 2015

2. Parallel Lives: Lesser Lives, Partial Lives and Mythic Lives

The question why women photographers? rather than photographers tout court is a complex one. In terms of scholarship and exhibitions, there are, of course, many reasons to recover those who were obscured or forgotten and whose work merits attention. And the not altogether unrelated factor of a thriving market in vintage photographs is also a motor of research. Nevertheless, a persistent issue underlying this query is whether the cultural production of women should be considered with respect to sexual or gendered difference (these are not the same) 15. Particularly in the period where the nature and terms of the new woman provoked such heated debate, socio-cultural anxieties, and collective fantasies, it is worth reflecting on how women themselves represented their modernity.

However, as a marked term, “women photographers,” like “women artists” can be a Procrustean bed, especially if it assumes an a priori notion of difference or posits the existence of a separate frauenkultur. Where and how might we identify the manifestations of gender and/or sexual difference in the work of women photographers? On the evidence, these are not particularly evident except in certain genres such as self-portraiture, or more generally, in forms of self-representation. But that is not to say that the fact of their sex is beside the point. For example, a secondary, but related issue is to do with the neglect of those women partnered with prominent male figures – Lucia Moholy with Moholy-Nagy, Lee Miller with Man Ray, Irene Bayer with Herbert Bayer, Dora Maar with Pablo Picasso – all of whose works were eclipsed when not obscured by the fame of their companions. But the redundancy of categories such as “male artists in Surrealism” or “male artists of the Bauhaus” makes clear why it is important to insist on the determinations of gender and thereby to recover the women who actively participated in the creation of modern – and modernist – photography. 16

The three women whom I can only touch on in light of these questions – Germaine Krull, Florence Henri and Gisele Freund – had parallel lives in many if not all ways and were close contemporaries 17. All had established reputations by the late 1920s or mid- 1930s; all were expatriates. All were multilingual; all had paper marriages to secure their residency status in France; all had unconventional sexual lives, all had (for various periods) their own photographic studios, few of which prospered for any length of time. For much of their lives, they were single women with limited immediate or extended families, and all were childless. Thus, like many single women, then and now, they got by with the help of their friends. And with respect to Freund and Krull’s friendships with Andre Malraux, among others, these relations may have saved their lives. All, however, were represented by important photo agencies and had their pictures reproduced internationally; all knew one another in Paris (Freund took some photography lessons from Henri) and all moved in intersecting social, literary and artistic circles (e.g., Robert and Sonia Delaunay, among others). All had either romantic or friendly relations with major male figures in artistic, literary and political circles including Lucien Vogel, the director of Vu 18. Freund worked primarily in portraiture and in the recently minted category of photo reporter; Krull produced for numerous markets; Henri produced portraits, nudes, advertising images and her personal artistic work.

As for their differences, these were of class, [nominal] religion, formation and geography. Krull was born in Poznan Poland, shortly to become Germany. Her mother was well to do, but her father \ had various business failures and abandoned the family. Freund was the highly educated daughter of a prosperous secular Jewish family from Berlin and her father was an important art collector. (Her parents and brother fled Germany for London in 1938). Freund received her doctorate at the Sorbonne in 1936, for what became a classic study of 19th-century French photography, wrote numerous books, produced various reportages, and had many connections with the German and French intelligentsia. Krull was a naturalized Dutch citizen, thanks to her marriage with Ivens, but she too had to flee Vichy France because of her youthful political enthusiasms. Henri, like Freund, also from a wealthy family, was born in New York to a French father and Silesian mother, trained as a pianist in Rome, Paris and Berlin, and was naturalized as Swiss thanks to a paper marriage. The Occupation turned Krull and Freund into refugees, Krull in Brazzaville, Freund in Buenos Aires and then Mexico City., Henri withdrew to the French countryside in 1940 where she remained until her death. Of the three, only Freund had a life-long career as a photographer. Henri worked in the medium for only in a 12-year period after which she returned to painting. After Krull became the proprietor of a hotel in Bangkok in X, she no longer worked as a professional photographer.

Germaine Krull, “Métal”, Paris, A. Calavas, 1928, portfolio, cover and heliogravure plates, 30×23,5cm. Collection Bouqueret-Rémy.

Yet closer examination of their lives and works suggest why manifestations of sexual and gender difference with regard women photographers of this period requires contradictory answers: no, yes, and maybe. No, because in most cases, and especially with work produced for the printed page, for advertising, for editorial, fashion or other mass media, there is little to self-evidently declare it as the production of women. Especially in photojournalistic and reportorial contexts, it is not distinguishable from that of their male cohort. As for Krull’s more innovative production from the mid- to late twenties or early 30’s, even Michel Frizot’s admiring catalogue essay acknowledges the relatively brief period during which her work was particularly innovative In this respect, the characteristic syntax of new vision photography – extreme close-ups, unconventional cropping and viewpoints, photograms, photomontage, and other experimental approaches, the Russian-derived formalist notion of ostranenie (making strange the familiar), bird’s eye or worm’s eye points of view, self-referential or other self-reflexive devices (cf., mirrors, reflections, shadows), as well as the celebration of all emblems of modern industry and technology – these were widespread and were, so to speak, unisex. One should note too the pervasive influence of the cinema, with respect both to photographic forms (e.g., close-ups, the representation of the metropolis, the mechanisms of montage, and so forth.). Krull’s relationship with Ivens, and her exposure to the films of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Guttmann was part of her visual repertoire as it was for many others.

There is, on the surface, apparently no gender specificity here, other than external knowledge of the maker’s identity, which has, however, its own discursive ramifications, positive or negative. Thus Krull’s book Métal (1928), which did so much to establish her professional and critical reputation (fragmented views of industrial structures, suspension bridges in Rotterdam and Marseille, the Eiffel Tower, etc.), earned her the moniker the “Valkyrie of Iron” 19 Whereas (needless to say) the male photographers who produced similar pictures, were not referred to as the Wotans of industrial modernity. Which is only to say that on the “yes,” side, one way in which gender (not sexual difference) operates is to mark the woman artist or photographer who traffics in what is implicitly understood to be “masculine” iconography as by definition an exception to her sex, like Brunhilde.

Marta Astfalck-Vietz, Experimental Dance, Berlin, 1931 © Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur, Berlin

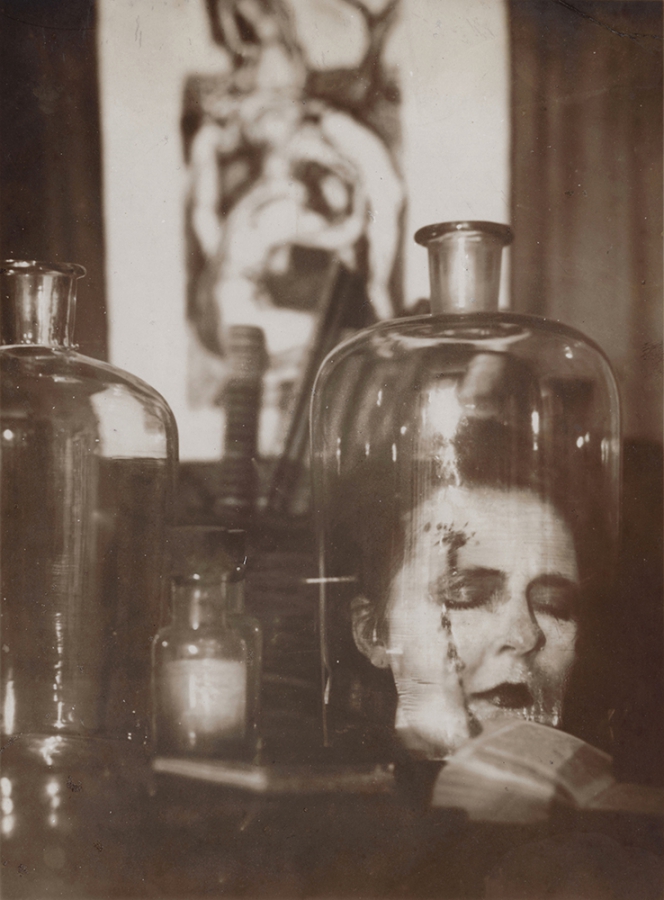

Yes too, but in very specific cases. Some of these are generic (e.g., certain approaches to self-portraiture, exemplified in Krull’s self portrait of 1935 and Henri’s self-portraits using mirrors and windows, as well as the work of other women in the period) 20. Other bodies of work where gender and difference are overtly at stake are singular, hermetic and idiosyncratic (e.g., the photographic work of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore) and thus must be considered on their own terms 21. But in the works of women photographers of the period there are instances of photographic self-representation that make unmistakable allusion to gendered identities. Among these are individual pictures or sequences that address the theme of femininity as masquerade such the 43 photographs of Gertrud Arndt “staging” herself under the series title Maskenselbstportrats. Using lace, veils, scarves, feathers, flowers and other regalia – many of them familiar accoutrements in the lexicon of fetishism, all of which invoke a certain “excess:” “[Arndt] shows herself as a femme fatale, a good little girl, as a woman of the world, as an Asian woman, as a childish brat, as a respectable creature, and as a widow 22.” Marta Astfalck-Vietz ‘s 1927 series of performative self-portraits should be also considered in this context. Similarly, Marianne Brandt’s self-portraits, and especially her photomontages, no less than Hannah Hoch’s and Grete Stern’s [postwar] photomontages, make explicit reference to the mythologies of the new woman, or to the entrapment or control of women. Another recurring trope in many women’s portraits and self-portraits is the emphasis on the force and power of the subject’s gaze, sometimes achieved through cropping and framing, and often minimizing signifiers of femininity or erotic allure. Or, where the image is abstracted, refracted, or otherwise “made strange,” often the setting of the studio affirms the artistic or professional setting within which the image has been orchestrated. This is equally the case in those self-portraits including the presence of the camera itself, sometimes obscuring the face as in Krull’s 1928 self-portrait, or partially so, as in Ilse Bing’s 1931 self-portrait. Herbert Molderings has justly noted that similar compositions in which the photographer’s face is masked by the camera are to be found among the works of many Neue Sachlichkeit, Bauhaus, and Nouvelle Vision photographers 23. But this fails to acknowledge the entirely different significance produced by a woman’s identification with an apparatus associated with empowered, indeed phallic vision. In other words, staging the overlap of the “camera eye” and subjective “I” does not have the same meaning when deployed by men or women. In all these respects, self-portraiture by women photographers, as a form of self-representation, is possibly the domain within which issues of difference are not only more readily identifiable, but where the very attempt to articulate that difference fostered [photographic] modes of expression that are a muted (that is, largely obscured or otherwise “unheard”) parallel to more familiar forms of modernist and avant-garde visual production.

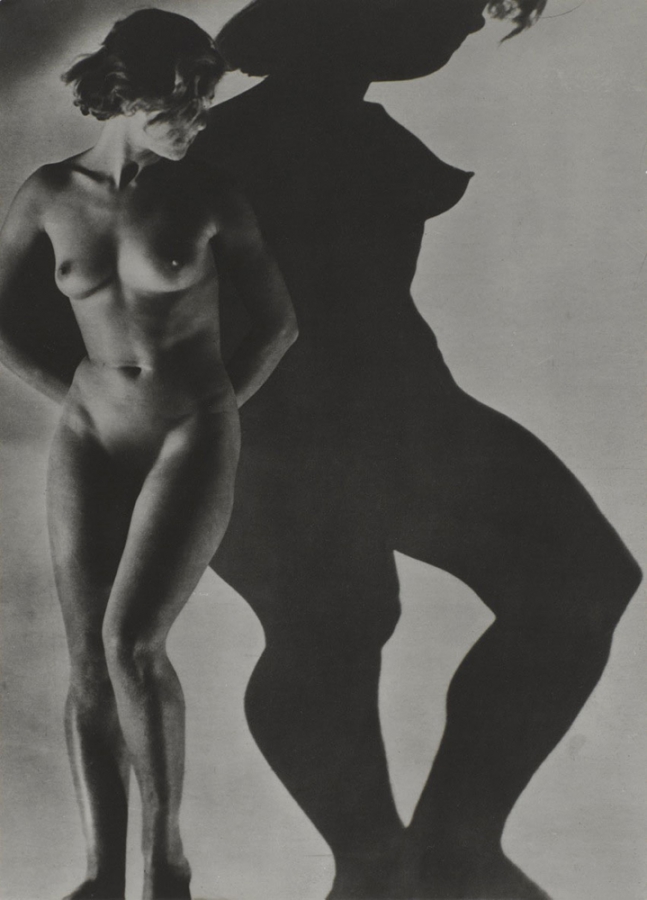

Another issue that bears on the question of difference is to do with the photographic genre of the nude, which is, in most pictorialist and modernist photography by default, a female body. 24 Krull and Henri, like many of their contemporaries (Ergy Landau, Andre Roger, Dora Maar, and others) produced numerous female nudes for which there existed, as always, an inexhaustible market spanning elite and mass culture. Man Ray, Emmanuel Sougez, and Brassai were adepts of the genre. But considering the photographs that Henri and Krull and other women contemporaries made of female nudes, some destined for erotic magazines, for art publications, or assembled into portfolios, there is some justification in speculating as to whether these might be said to express a woman’s desire. Or, minimally, to prompt some reflection on what is at stake in the reversal of conventional subject/object relations of male photographer and female model. In this particular context, and with respect to the articulation of difference, we have recourse to the equivocal “maybe.” Krull had made the female nude one of her earliest genres as early as 1919 when she opened her first short-lived studio with X.. Krull’s biographer Kim Sichel notes that certain of these nudes were sold to and reproduced in erotic publications, and she also produced nudes using her sister Bertha, a dancer, as a model as well as professional models, such as Assia. 25) Ergy Landau, briefly married to Andre Kertesz, also produced nudes, some of which too were intended for the erotic magazine trade. But it is Krull’s series, euphemistically titled Les deux amies, a series of 11 photographs made in 1924 (Frizot thinks there were originally 12 as would be logical for a publication) depicting two women undressing and making love that warrants some discussion. 26 Although Sichel characterizes this sequence as “playful,” and not necessarily indicative of identification or identity, this is not at all self-evident. Which immediately prompts the question of whether women photographers could simply occupy the conventional masculine viewing (and objectifying) position, or as professionals, skillfully mimic it,(dutifully repeating the conventions of this genre, artistic or erotic). Femininity has itself been theorized, at least since Joan Riviere (1921) and continuing though Judith Butler, as performative, although it doesn’t seem to be the case that either Freund or Krull’s self-presentations were in any way glamorous or alluring. But one may ask what is going on in those photographs by Henri, and Krull where the fetishism that underwrites all representations of the female body appears to be quite knowingly accentuated. Does the use of conch shells, black gloves, leather belts, lilies, as well as other props constitute an acknowledgment and reiteration (conscious or not) of this fetishism, or might it be considered an instance of female fetishism?

Such questions – and they are, of course, questions –assume that with respect to the photographic act, it is at least thinkable to posit the existence of women’s desire. But a desire that is not confined by labels such as “lesbian, ” an identity that none of these women affirmed. To be sure, until recently, the bisexual or lesbian identities of women artists and photographers were not officially acknowledged, for obvious reasons. 27 But as in Weimar Germany, interwar Paris had various lesbian and gay subcultures, while the sexuality of women photographers seems mostly to exist in the domain of the non-dit. 28) Although Krull wrote in her ostensibly candid memoir that she had had one important affair with a woman, neither Freund nor Henri ever made any [published] reference to their own sexual preferences. Nevertheless, Freund’s liaison with Adrienne Monnier and her friendships with gay women such as Janet Flanner were not at the time secrets. And reading between the lines, it seems likely that one of Henri’s lovers was Margaret Schall, although this is described in the literature as a devoted friendship. But looking at Krull’s sequence of the “lesbian” amies, or Florence Henri’s 1934 series of two models, one sporting a leather belt and nothing else, it seems legitimate to pose their identifications or projections as an open question which I leave precisely as a “maybe”. 29

Reflecting on the remarkable numbers of women photographers as well as their significant achievements in interwar Germany and France, what if any general observations can be hazarded? Sociologically speaking, among this group, it is striking how many of them, notably those from Germanophone and other eastern countries, were Jewish, although from entirely secular, middle-class or well-to-do backgrounds. Thus, it seems that however many women (and men) photographers were architects of the new vision photography — whether produced for artistic, commercial mass media circuits— these had their wellsprings in the east and from there were propagated, adapted, dispersed and popularized.

Clearly, few of these women were French-born, probably the consequence of French laws that relegated women to the position of minors. 30 Certainly the far greater constraints on French women’s economic and professional freedoms were significant limitations. 31 A bourgeois, Catholic French woman, contemporary to Krull or Henri was unlikely to be encouraged by her family to attend a technical school or apprentice herself to a photographer. But among the group to which Krull, Henri, and Freund are affiliated, none of them – and this seems be the case with most of the new women photographers of the period –appear to have had any relationship to the feminist movements in Weimar Germany, the Netherlands, or France. 32 Although the multiple feminist organizations and formations suffered serious setbacks in France after the Armistice (less so in Weimar, but even so, these all lost traction through the 1920s), it is as though these women, living their relatively free and unconventional lives, defined themselves so individualistically as to have no need (or interest) in collective struggles for women’s emancipation. 33 Moreover, it also appears that while most of the women photographers active in Germany and France were antifascist, few of them, with important exceptions, were activists; few were involved in the Popular Front, and few were activist supporters of the Republic in civil war in Spain, But, it must also be noted ,few had French nationality. 34

For Krull, Freud and their cohort, their collective circumstances as exiles and expatriates (and with the advent of the Second World War, as refugees), inevitably shaped their lives after 1939. But the no less important determinations of their sex, their sexual identities and identifications in their professional as well as personal lives should not be discounted. These are themselves marked by paradox, contradiction, ambiguity within which regimes of representation are shaped by capitalism and patriarchy and heterosexual presumption. In any event, it is less important to argue now for their individual importance or stature as artists – still an honorific category as opposed to photographers – than to acknowledge their significance as shapers of modernist visual culture. And although harder to empiricially document, like invisible ink, the markers of difference, such as they are, can only be read in and with a certain light.

Abigail Solomon Godeau, 2015

References

![August Sander, “Mère et fille” [Helene Abelen avec sa fille Josepha], vers 1926 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur - August Sander Archiv, Cologne; ADAGP, Paris, 2015.](../../../wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ASA3-14-6307.jpg)