Diana C. du Pont’s text is excerpted from her essay for the 1990 catalogue Florence Henri: Artist-Photographer of the Avant-Garde, published by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

To the extent possible, the photographic reproductions presented here match those in the original publication. However, due to copyright limitations, there have been some minor additions and deletions. Translated and reprinted by permission of the author and

the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. All rights reserved.

If in Henri’s hands the mirror was the ideal instrument for manipulating space and form to create pictorial ambiguity, it also provided the perfect tool for the analysis of self. Her own image is a recurrent theme in Henri’s photographic oeuvre and the mirror figures in almost every self-portrait she made.

Before the advent of photography, the mirror was an essential tool for artists in creating self-portraiture. The earliest account of an artist’s use of the device is Pliny’s report of laia of Kyzikos, a painter in Rome during the time of Marcus Varro (116-27 BCE), who painted a portrait of herself using this method. 1 Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Sofonisba Anguissola (1527-1625), and Rembrandt (1606-1669), whose examples of self-portraiture represent the earliest ongoing expressions of the genre in the history of Western art, also used the mirror to capture their own images. 2 But the link between mirrors and self-portraiture extends beyond the merely practical. Throughout the history of art, the mirror has also served as a symbolic motif within the picture frame, representing a broad range of ideas extending from philosophy, prudence, clarity, and knowledge to vanity, narcissism, transience, and death. 3 In Henri’s self-portraits, the mirror is a metaphor for self-knowledge.

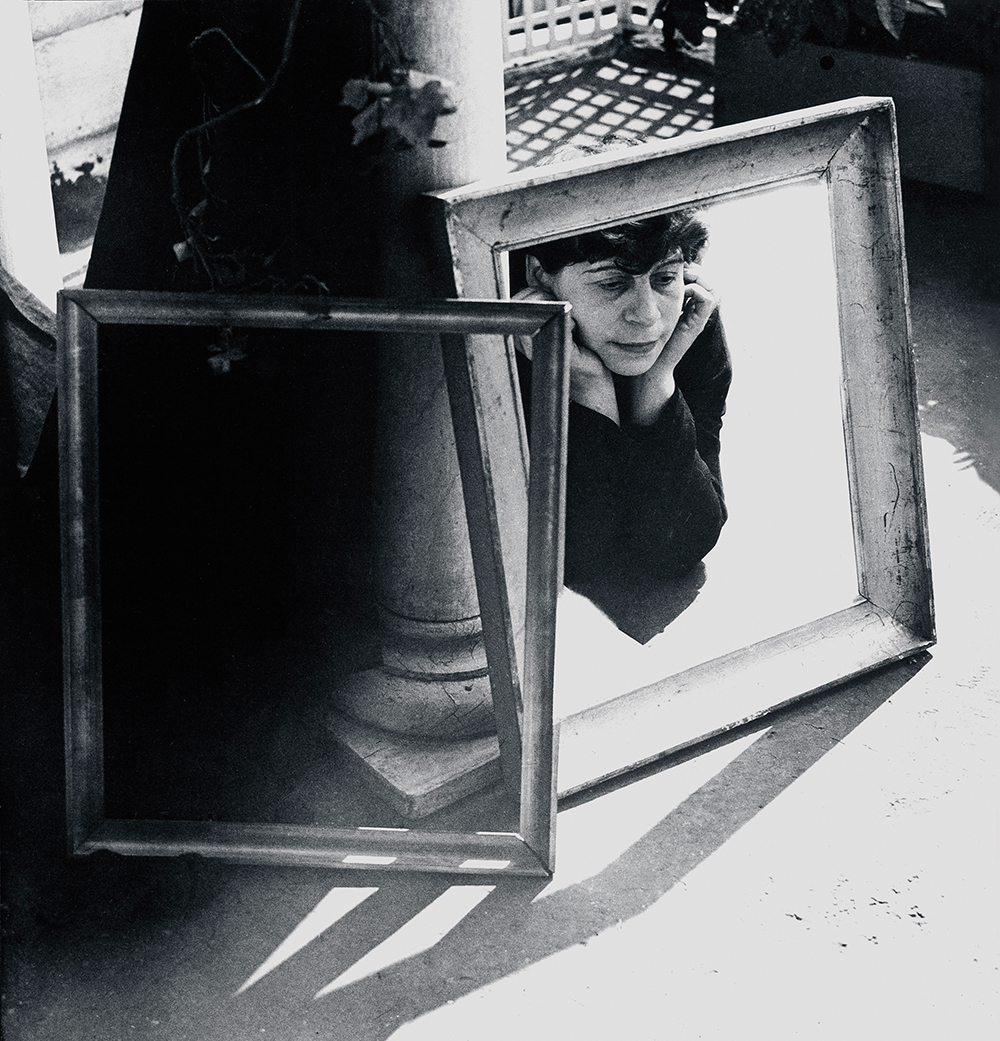

Florence Henri, Self-portrait, 1938. Gelatin silver print dated 1970’s, 24,8 x 23,1 cm.

Private collection, courtesy Florence Henri Archive, Genoa. Florence Henri © Galleria

Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa

Self-portraiture as a serious artistic pursuit emerged during the Renaissance as part of the artists’ steadily increasing belief in their self-worth as they moved up from the artisan and mercantile classes to the intellectual and aristocratic realm. The genre’s subsequent history charts artists’ preoccupation with themselves and with changing conceptions about their role in society, but these definitions have not always been the same for male and female practitioners. The phrase “separate but unequal” aptly suggests the gendered organization of artistic practice that was dominant through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. 4

Henri, born in 1893, entered a world in which the Romantic concept of the artist as « Bohemian genius » still lingered, a notion largely identified with masculinity. 5 This view of an artist as untamed but sublimely inspired, and essentially male, paralleled the development of a mainstream bourgeois class that believed that a woman’s place was in the home. Femininity signified the bearing and rearing of children and the moral duty to protect and civilize society through fulfilling maternal responsibilities. Expected to dedicate themselves to domesticity, women of the nineteenth century who dared to live otherwise endured a societal bias that led to a profound collision between woman as professional and woman as mother. The particulars of Henri’s life do not conform to the conventional bourgeois mores that reinforced these notions of womanhood well into the twentieth century. Her lack of a traditional home life, her cosmopolitan upbringing, her marriage of convenience, and her liberal attitudes toward sexuality challenge the domestic ideal. Henri chose to live her life as an artist, and in building her identity, she turned to both the self-portrait and the mirror.

The mirror and its relationship to personal identity is discussed by Simone de Beauvoir in her book The Second Sex (1949), widely acknowledged as a milestone in the history of feminism. Beauvoir, echoing Jacques Lacan, sees the child’s first affirmation of its personhood the moment it recognizes its reflection in the mirror; eventually, she observes, the ego becomes so fully identified with the reflected image that the self is encountered only in a projected form. 6 While Beauvoir speaks here of the human condition in general and its connection to the mirror — to this “sheet of light” 7 that affirms the dual nature of the self as observer and observed — her subject is woman, and she “holds up the image of the mirror as the key to the feminine condition.” 8 For Beauvoir, the mirror plays a crucial role in a young girl’s transition from childhood to adolescence through metamorphosis into a sexual being. “The adolescent puts away her dolls,” she writes. “But all her life the woman is to find the magic of her mirror a tremendous help in her effort to project herself and then attain self-identification.” 9

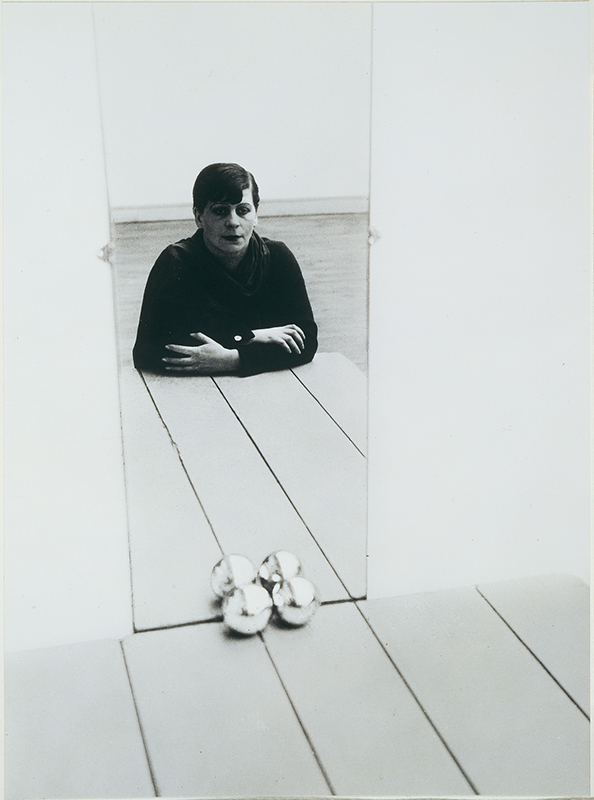

Florence Henri, Self-portrait, 1928. Gelatin silver print, 39,3 x 25,5 cm.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek Florence Henri © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa

Through her self-portraits Henri came closer to the personal and instinctual side of her nature. Divided into two groups separated by a decade, her self-portraiture dates from the late twenties and the late thirties. The earlier group, made in Paris in 1928 during her first year as a practicing photographer, includes her most notable self-portrait, her image with a mirror and two balls. 10 Situated in the same studio and at the same table as the unidentified young man in her earlier mirror portraits, Henri confronts the viewer by means of her image reflected in the mirror that frames her. The internal framing achieved by the vertical mirror is the pivotal aspect of the self-portrait, for with the two chrome balls at its base it forms an abstracted penile shape. 11 Henri sees herself in the image of masculine power, but instead of being consumed by it, she accepts it as her due. She assumes dominion for herself and engages in a dialogue with this symbol of masculinity by suggesting a double reading of the balls as both female breasts and male genitalia. Here, as in other self-portraits of the same period, she does not resort to the conventions of self-portraiture in which the artist presents the tools of the trade 12. Instead, she embeds her creative persona in her constructed, self-conscious compositions. There is an intensity of expression and a mood of self-possessed contemplation in all these early self-portraits. Confronting her image in the mirror, Henri addresses herself, and her singular presence forges a personal and artistic identity that is pensive, but also tough, determined, and independent.

Florence Henri, Self-portrait, 1938, Gelatin silver print, 22,7 x 28,7 cm © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa

The self-portraits of the late thirties continue the meditative, even melancholy, mood that characterizes the earlier self-portraits. These later images give equal attention to the human figure within a structured environment, but there are differences, especially in Henri’s personal fashion. The short haircut with its severe lines that defined her look of the twenties is gone. Instead, she now wears long hair, pinned up and softened with curly bangs. By far the most significant difference is the new dialogue between interior and exterior space. In the self-portrait of 1938 in which she is seated at a table strewn with packages of cigarettes, she has collapsed the inside and the outside, creating a complex composition abundant with spatial conundrums. The patio and table merge, joined by the artist’s bold handling by which she cleverly abuts her image at the table with another view of the same table taken from a different vantage point. The visual and intellectual energy of the piece derives from this manipulation of contrast, through its fusion of two distinct spaces and times and through its effective play of light and shadow. The natural light that floods through the windows serves as a strategic device that breaks down the barriers between interior and exterior and is matched by Henri’s gaze, which is directed outward. Here she looks through a window rather than at a mirror, which would have reflected her image back inward. 13

In another self-portrait of 1938, Henri moves herself outside. On her apartment patio, she constructed a still life composition consisting of a garden-size Roman column on the capital of which she placed drapery and sprigs of ivy and at the base arranged empty picture frames. It is in one of these frames that Henri herself appears. Comparison of this image with a variant demonstrates how Henri masked the space around her to transform the empty frame into a mirror, once again revealing her fascination with reflected images and their special ability to juxtapose reality and illusion. Among the late self-portraits, this image in particular speaks specifically about Henri the artist. Conceptual at its root, it is a premeditated exercise in which Henri uses symbols of art to express the life of her mind: the classical column signifies the ancient tradition with which she associates herself, while the picture frames at its base represent the creative act of making art.

Florence Henri, Self-Portrait, 1938. Gelatin silver print, 36,3 x 28,1 cm © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa.

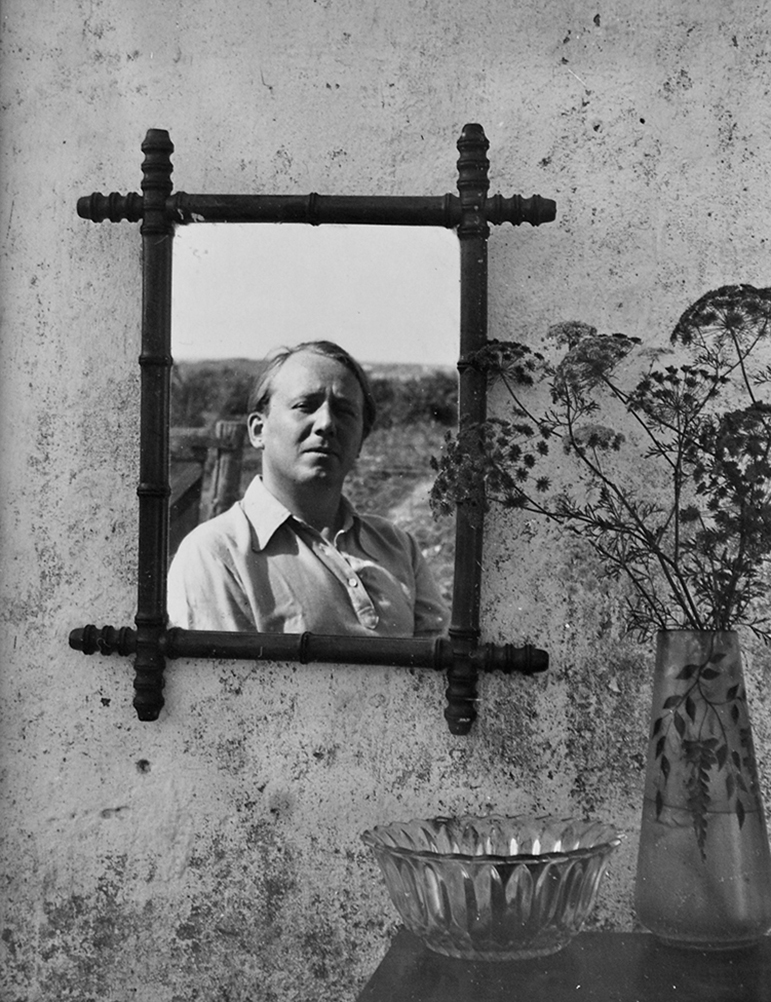

Florence Henri, Portrait of Pierre Minet, 1938. Gelatin silver print, 49,5 x 39,5 cm

© Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa.

Henri’s efforts to bridge art and the intellect with nature are perhaps most clearly evident in her late self-portrait made in Brittany. This image and its companion piece, her portrait of the French poet and novelist Pierre Minet, display Henri’s visual and intellectual game-playing at its best. For these works, too, she created a still life, in this case consisting of a bowl, a vase of flowers, and a mirror on a wall. If in the self-portrait made on her Parisian patio, Henri transformed the picture frame into a mirror, here she achieves the reverse: the mirror reads now as a framed photograph. Bewitching as this conversion is, it only partially explains the magic of these images. Additionally mesmerizing is that both Henri and Minet are seen in full sunlight against the open fields of Brittany. Once again Henri confounds the relationship between the interior space of still life and the exterior space of landscape. There is an intent here to identify with nature and, indeed, Henri appears as a woman of the country. The urban style that marked her self-portrait with cigarettes is replaced here with a basic cotton shirt and what appears to be a simple hairdo covered with a bandanna.

Henri’s self-portraits of the late thirties are distinguished by their new sensitivity to nature, while continuing to thrive on the intellectual challenge that marks those of the twenties. As opposed to the self-absorbed mood and the confined, even claustrophobic, space of the early self-portraits, these later works open themselves up to the world. By the same token, the artist herself begins to look outward, to find a balance between art and nature.

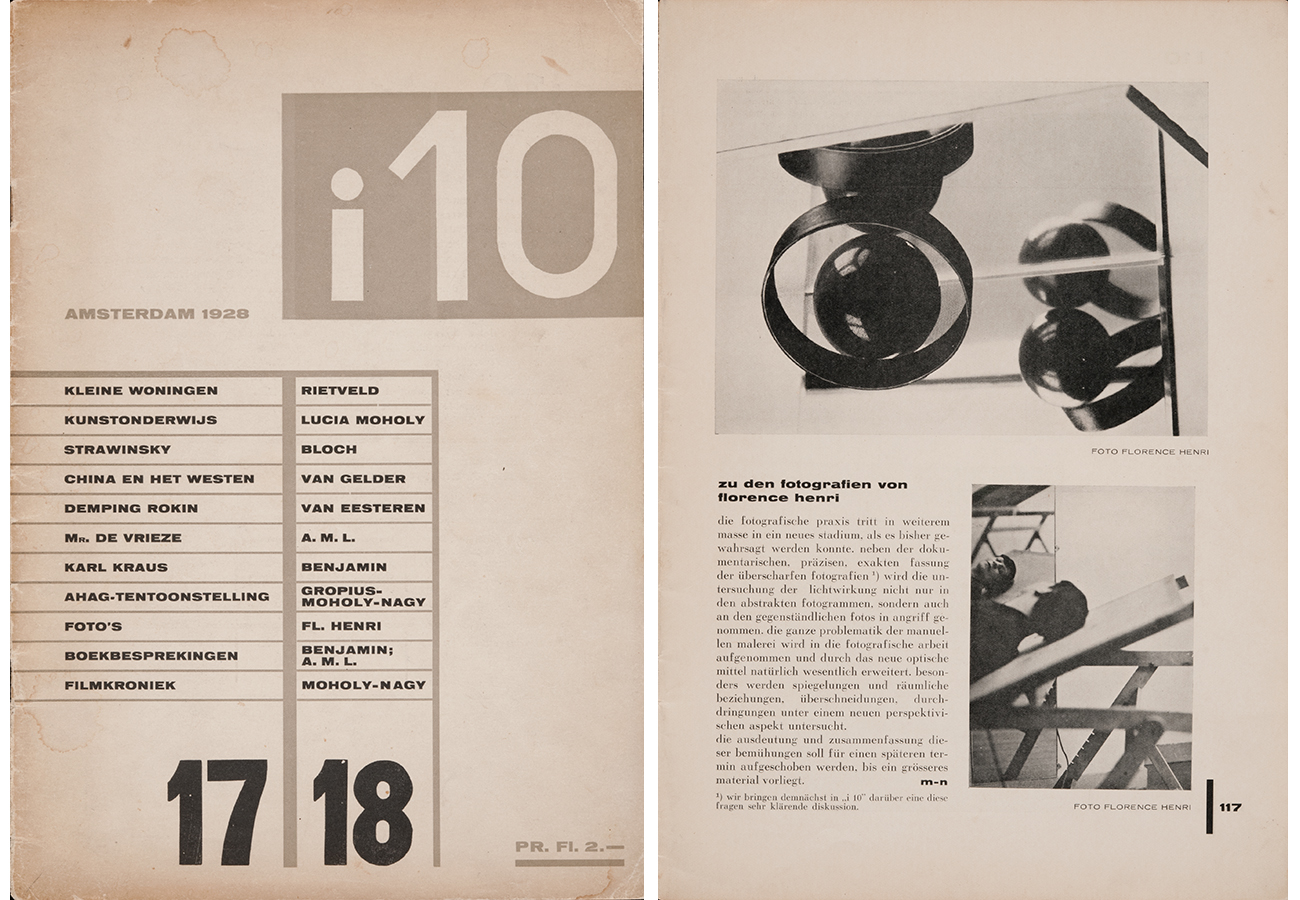

i10 n° 17/18, Amsterdam, 20 décembre 1928, László Moholy-Nagy, « Zu den Fotografien von Florence Henri », © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa.

Henri’s personal explorations invite a consideration of how they were accepted by her immediate circle for, in principle, they were at odds with the ideals of the Parisian world with which she was closely associated. The emphasis on the objective and collective over the subjective and the individual actually denied a place for self-portraiture. Seuphor chose one of Henri’s mirror and object compositions rather than one of her self-portraits for reproduction in Cercle et Carré. Moholy-Nagy reproduced one of her self-portraits in i10 but did not acknowledge the work as such. To him the figure was anonymous and secondary to his fascination with the way in which it was integrated into a structured space and how Henri used mirrors as a means of offering new perceptual experiences.

Henri’s images of herself actually share a kindred spirit with the Surrealists, particularly the women artists associated with that movement. Surrealism called for a probing examination of the psychological and sexual dimensions of human experience, and while male Surrealist artists pursued this quest by projecting their desires through “mythologizing the woman as muse,” 14 women artists in the Surrealist circle, including Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Dora Maar, or those adopted by it, such as Frida Kahlo, looked inward to find self-truth. They instinctively fostered an intimacy with the deepest part of themselves, and consistently relied on the validity of their individual experience as the source of their art. 15

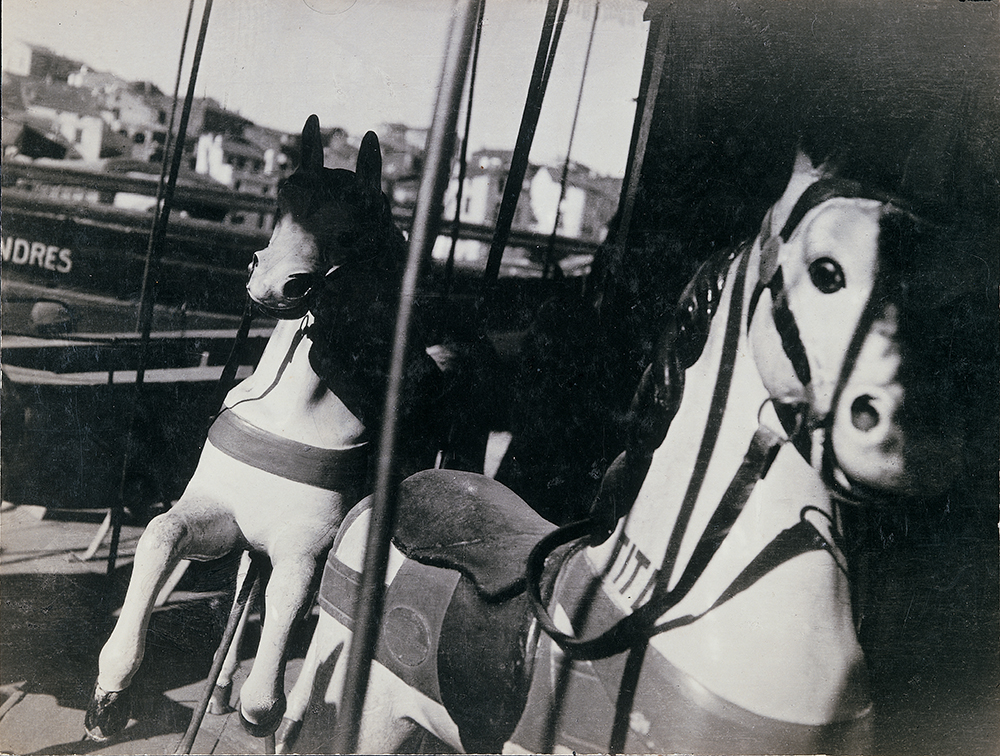

Florence Henri, Carousel (Two horse carousels in shadow), 1928. Gelatin silver print, 22,0

x 28,8 cm. © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa.

If Henri was not a Surrealist and did not even associate with the Surrealist circle, if in fact her circle consisted of those very artists who waged an organized campaign against Surrealism, how then account for the dreamlike and self-absorbed qualities that frequently characterize her work? Although connected to the anti-Surrealists by friendship and aesthetic philosophy, Henri herself was not an extreme isolationist. She exhibited alongside avowed Surrealists in numerous photography exhibitions, 16 and published her photographs in illustrated magazines that had an interest in Surrealism, such as Variétés, 17 and in such annual publications as Photographie, 18 which were interested in celebrating the new photography in its various forms. In fact, Henri explored themes dear to the Surrealists. Beside her intense self-examination and the use of the mirror to reinforce that personal search, there is a fondness for the phenomenon of reflection and experimentation with enigmatic shadows and artifacts of popular culture, such as the archetypal carousel horse and the store mannequin. 19

![Florence Henri Mannequin de tailleur [Tailor’s mannequin], 1930-1931 gelatin silver print, vintage 17,1 x 22,8 cm Private collection, courtesy Florence Henri Archive, Genoa Florence Henri ©Galleria Martini & Ronchetti](../../../wp-content/uploads/2014/02/FlorenceHenri_05__MannequinDeTailleur-2.jpg)

Florence Henri, Mannequin de tailleur [Tailor’s mannequin], 1930-1931.

Gelatin silver print, vintage, 17,1 x 22,8 cm. Private collection, courtesy Florence Henri

Archive, Genoa. Florence Henri © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa

Yet, no matter to what degree Henri’s work paralleled that of the Surrealists, it was always marked by the rhetoric of Cubism and Constructivism. One sees this unique synthesis in the self-portraits, in particular, and perhaps this approach was the result of Henri’s striving to find her own expression in languages she herself did not develop. Cubism and Constructivism were largely the products of the male mind, and having learned them through Léger and the Académie Moderne, Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus, and Mondrian, Seuphor, and the Cercle et Carré group, she sought ways to personalize them. The mirror offered one solution, her own image another. While Henri’s intense focus on herself does indeed strike a chord with Surrealist manifestations, her self-portraits are not psychosexual investigations into the depths of her unconscious mind. Rather they are attempts to define herself as a modern woman and artist.

Diana C. du Pont, 1990

Links

Exhibition at Jeu de Paume, Paris “Florence Henri: Mirror of the avant-garde, 1927-1940”

The Selection of Jeu de Paume’s bookstore

Notes

References