By Herbert Molderings & Barbara Mülhens-Molderings

Until two decades ago, modernism in photography was considered to be the achievement of male photographers alone. Although the names of female photographers crop up here and there in classic works on the history of photography, the leading roles in the revolutionization of form and function in the photography of the 1920s were ascribed exclusively to men. Even Michel Frizot’s “The New History of Photography” of 1994, a work which counters the stereotyped notions of photography’s historical development with a multitude of new perspectives, has remained true to this tradition. During the last decade, however, a great many exhibitions and publications have drawn attention to the significance of the part played by women in the development of the new style of modernist photography.

The social changes during the First World War gave fresh impetus to the women’s liberation movement. Whilst the majority of men were conscripted and many lost their lives – or at least their health – in the war, the survivors returning home without any sense of purpose or orientation, women had had to take their place in both public and private life and had done so with enormous initiative and inventiveness. The self-confidence which women had gained through these changes no longer fitted in with the social constraints of the Belle Époque or the Wilhelminian Monarchy, for these changes had been far too radical. The values of the 19th century had lost all their validity. Thus it was that a whole generation of men, who first had to come to terms with their experiences of the war and regain their place in civilian life, were confronted by the phenomenon of the “New Woman” in all walks of life, whether as shop assistants or clerks, artists, photographers or actresses, physicians or writers.

The “New Woman” – also known as a “flapper” or “garçonne”1 – soon epitomized the 1920s and, with her bobbed hairstyle, straight shift dress and long cigarette holder, was to be found everywhere in Europe. In Germany, where the Weimar Constitution of 1919 had for the first time guaranteed women’s suffrage and the right to study at a university, the “New Woman” was the “epitome of Weimar modernity”, a symbol “of our Republic’s modern progressiveness, its urbanity, its enthusiasm for technical advancement, its objectivity and its democratic image.”2 Otto Dix immortalized her in his famous portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, painted in 1926 (Coll. Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou).

Their enthusiasm for these values and the opportunity of expressing themselves artistically or journalistically led many educated young women to work as professional photographers. It was both through the development of lightweight, hand-held cameras (Ermanox, Rollei, Leica), which now relieved professional photographers, especially press photographers, of their heavy equipment, and through the enormous growth in illustrated magazines, many of which were aimed at a female readership, and the resultant sudden increase in the demand for photographers, that a completely new profession had now opened itself up to women in the field of commercial and industrial photography. Finally, during the 1930s and 1940s, women conquered the last male bastion of professional photography, that of war reportage. Gerda Taro, Germaine Krull, Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White were the most famous among them.

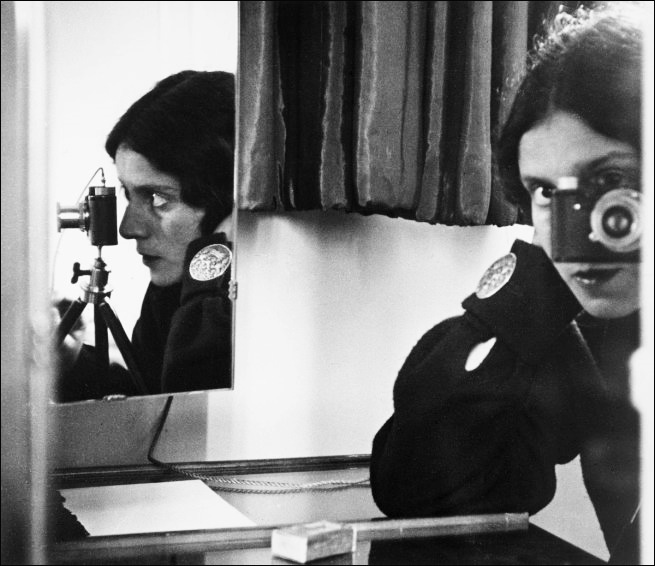

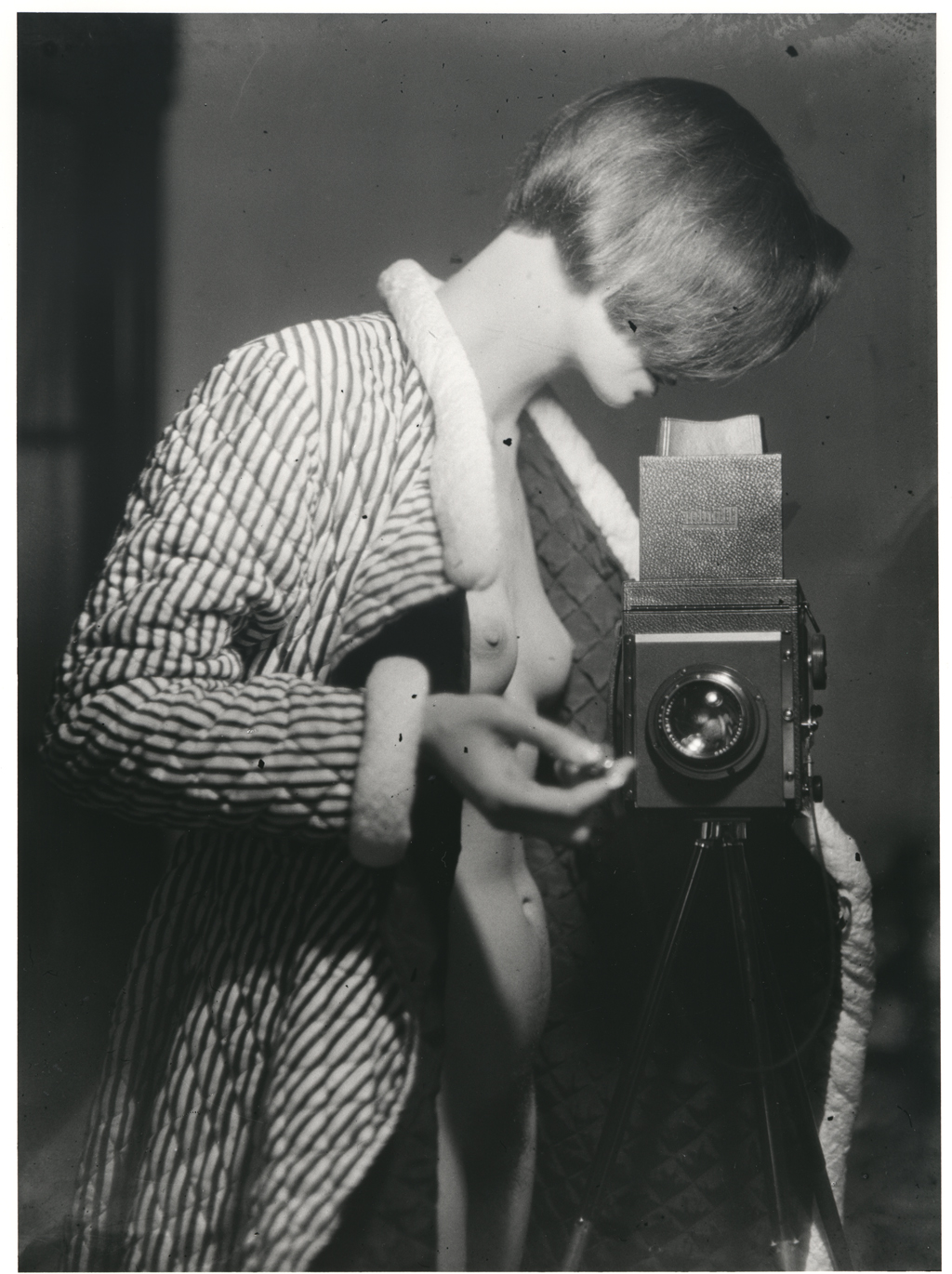

Germaine Krull, « Selbstporträt mit Ikarette », 1925, Sammlung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Zülpich © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen. Courtesy : Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde / Pinakothek der Moderne München, 2011

The woman’s break with her oppressive pre-war image, her new liberties and her new vocational prospects, the shape and scope of which were still extremely unclear, found expression in the multitude of self-portraits taken by female photographers of the 1920s in an attempt at defining and asserting their new identity.

Germaine Krull was the very prototype of the “New Woman”: a young entrepreneuse – she had set up her own portrait studio in Berlin in 1923/24 (together with Gretel and Kurt Hübschmann)3 – with bobbed haircut, cigarette and bisexual inclinations, she almost ideally conformed to the typical image of the “New Woman” as portrayed week be week – whether admiringly or otherwise – in the art periodicals, women’s magazines and illustrated weeklies of the Weimar Republic.

In 1925, Germaine Krull photographed herself in a mirror with a hand-held camera which half-covered her face. The camera is focused on the foreground of the image, such that the lens and the two hands holding the camera are sharp, while the face behind the camera is blurred. This self-portrait has given rise to many a feminist or professionally critical interpretation, ranging from the female domestication “of the masculinity of technical apparatus”4 through to the analogy of the camera with a weapon used by the photographer to “reduce the person opposite her […] to an impotent object”.5 However, if we attempt to interpret the photograph not so much in a figurative sense as in a concrete, phenomenal sense, we arrive at a completely opposite conclusion. By selecting the depth of field in such a way that only the camera and the hands are sharp, Germaine Krull has isolated her act of photographing from her subjectivity and individuality as the photographer. It is the technical apparatus, the camera, which is the focal point of the image and behind which the photographer’s face is blurred beyond recognition. We may assume that this physiognomical retreat behind the camera is less a typical feminine gesture of shyness and reticence than the characteristically ideological approach of a modernist photographer. There is one critical point in Krull’s portrait of herself as a photographer which gives us good reason to make this assumption, namely the fusion of the photographer’s eye with the “oculus artificialis” of the camera. The notion that the camera lens could not only replace the human eye as a means of capturing the world visually but also improve upon its ability to penetrate reality to its invisible depths was paradigmatic of the new, basically positivist photographic aesthetic of the 1920s. It is an aesthetic defined by the Bauhaus theorist László Moholy-Nagy in his manifesto “Painting Photography Film” in 1925 and visualized by countless collages, posters and book covers of the 1920s and 1930s depicting the camera lens as a substitute for the human eye. Germaine Krull’s self-portrait wholly identifies with this new photographic aesthetic, too. Indeed, her influential work “Métal”6, a photographic eulogy of modern technology published in 1928, is its embodiment.

It is in the context of this Constructivist aesthetic that one might easily be tempted to interpret the fusion of face and camera as a typically male approach to technology. After all, we are familiar not least with Andreas Feininger’s famous portrait of the “Photojournalist” of 1955, in which not only one eye but both eyes of the photographer have been replaced by optical lenses, making his face look like that of an android. However, a comparison of this photograph with the self-portrait of the Swiss photographer Fred Boissonas, taken around the turn of the century, makes us cautious about making such gender-specific interpretations.

Fred Boissonnas, « Selbstporträt mit Kamera » , 1900, Archiv Borel-Boissonnas © Fred Boissonnas. Archives Borel-Boissonnas

In this self-portrait of the photographer holding a twin-lens stereoscopic camera, the eye of the camera and the human eye are not yet congruent. Both of them, the mechanical eye and the still visible human eye, are on a level with one another. The photographer holds the camera trustingly against his cheek, looking at them searchingly and with a certain tenseness. Does he already suspect that this robot-like head with its two glass eyes will soon gain supremacy over human vision? The relationship between the photographer and his camera, expressed here in the juxtaposition of the human and the optical eye, reflects the reserved, critical attitude of the Pictorialists towards the photographic lens at the turn of the century. – Imogen Cunningham, a professional photographer since 1906, had photographed herself in a similar pose with a large-format camera in 1933.

Imogen Cunningham, « Self-Portrait with Korona View » , 1933 © The Imogen Cunningham Trust / www.imogencunningham.com

Because the camera did not reproduce the world as people perceived it through their senses but as an unfeeling lens perceived it, the Pictorialists considered the photographic image to be an impersonal and hence false and distorted image of reality. They therefore sought to reduce its “merciless sharpness”7 with the aid of soft-focus lenses and complicated transfer printing processes, thereby suppressing all that was inessential and emphasizing those characteristic features which conformed to the subjective, reminiscent and emotional way in which the human eye perceived reality. Truth as the eye saw it and truth as the camera saw it did not become identical until the inception of modernism in the 1920s, when the human eye and the optical eye were finally thought to be congruent.

Nevertheless, Krull’s “Self-portrait with Ikarette” is in no way identical with Andreas Feininger’s “Photojournalist”. What differentiates it from the latter is the silent dialogue between the camera and the hand holding the cigarette in the centre of the photograph. If we covered up the hand, the photograph would be just an ordinary portrait of a female photographer – or of a male photographer for that matter, for the blurred face behind the camera and the short haircut could quite easily belong to a man, too. The elegant hand, however, with the ring on its small finger and the lighted cigarette poised between the index and middle finger, is definitely the hand of a woman. The way the hand gently caresses the camera with its ringed finger in order to steady it for the photograph robs the act of photographing of that aggressive aspect which derives, for example, from the likeness of the dark camera lens to the muzzle of a gun or from the metaphor of “shooting a picture”, thus lending this self-portrait an unequivocally feminine connotation. By leaving her own face out of focus and focussing on just the hand and the camera, Krull has transformed her self-portrait from the conventional genre of occupational portraiture to an emblematic representation of the photographic act. As such, this self-portrait is unique in the history of 20th century photography. If the technicized aesthetic of the “New Photography” of the 1920s is indeed to be viewed as the product of the male imagination – as far as we can see, female photographers had no part to play in its theoretical definition –, then Krull comments upon, and perhaps also corrects, this view through the decidedly and unmistakably feminine way she “handles” her camera. Whether and to what extent this attitude is reflected in her general work as a photographer is another question, and one which cannot be answered within the context of this essay.

Whereas the mirror in which Germaine Krull photographed herself is invisible in the photograph, the self-portraits of other female photographers, such as Ilse Bing, Florence Henri and Lotte Jacobi, show the mirrors explicitly. Indeed, the deliberate incorporation of the mirror is typical of women photographers’ self-portraits of the 1920s. Many of their male counterparts also photographed themselves in mirrors, but these photographs were mostly snapshot-like photographs of themselves at their work, reflected in the distorting convex surfaces of car headlamps (Renger-Patzsch, Umbo, among others) or in distorting mirrors (Kertész), and were rather optical curiosities than works of self-discovery or introspection.8

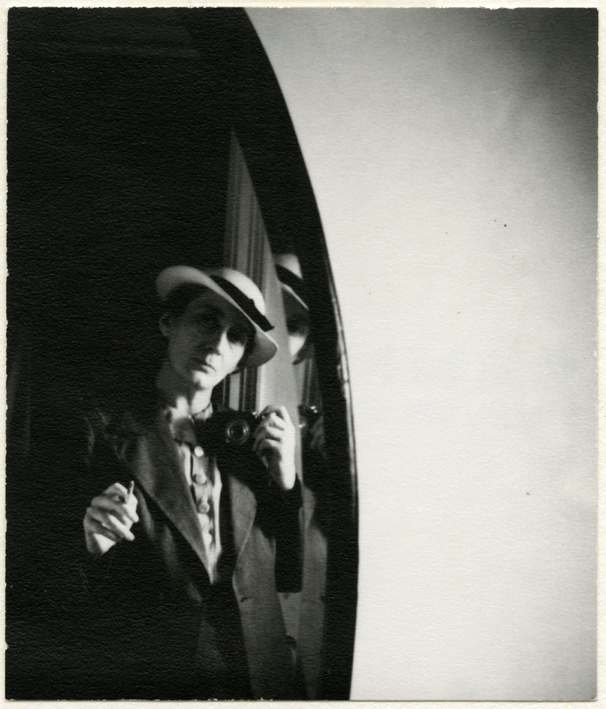

Ilse Bing, who decided to take up the profession of photographer in 1929, portrayed herself in 1931 in the traditional style of an occupational portrait. As a former student of art history, Ilse Bing was undoubtedly familiar both with the famous “mirror paintings” of van Eyck, Parmiganino and Velazquéz and with the genre of the “self-portrait of the artist in his studio”. In this self-portrait, the tripod and camera have replaced the painter’s palette and easel. The photographer has mounted her Leica on a table tripod and is looking across the top of the camera into the mirror so as not to lose sight of herself behind the viewfinder, obviously not wishing to view this self-portrait with camera through the camera itself. Unlike Germaine Krull – and, later, Andreas Feininger – Bing rejected the absolute identification of the eye and/or entire person of the photographer with the camera lens. Her somewhat aloof attitude towards the Constructivist ideal of the artist-engineer was altogether in keeping with her work as a photojournalist which was on the whole more akin to Kertész than to Moholy-Nagy and conveyed rather a romantically poetical than a Constructivist view of the world.

By integrating into her full-face mirror image a second image in profile, Ilse Bing creates a complex interplay of lines and angles of vision.9 Not only does she herself appear both as the subject and as the object of the work – as the viewer and the viewed – in two different perspectives, but she also guides the viewer’s gaze in a peculiarly circular manner, making the viewer the mirror, as it were, of her own self.10 Ever since Cubism, polyperspectivity has been part and parcel of the repertoire of modernism. In merging the full-face and profile images of herself, Ilse Bing indeed demonstrates the height of photographic modernism. The production of multiple portraits with the aid of mirrors had been the favourite pastime of amateur photographers since the turn of the century, the technique having been exhaustively described in many manuals on leisure11 and recreational12 photography. As an example of the use of this mirror technique in art, Marcel Duchamp’s quintuple self-portrait of 1917 has achieved a certain degree of fame. Bing’s “Self-portrait with Leica”, however, is more than just a “jeu de miroirs”, for the second, profile image also reveals another side to this woman photographer’s personality. The paradigmatic change in the modern photographic aesthetic of the 1920s, a change characterized by the rejection of the traditional principles of painting (Pictorialism) in favour of the scientific ideal of extended perception (Constructivism), was no isolated photo-historical phenomenon. It was bound up with a general utopian ideology which saw its revolutionary strength for the creation of a new human society not in any political struggle but rather in technology. It was not until this ideology finally exercised its influence that the photographic lens gained primacy over the human eye. “The hoped-for change in the world will […] come: not through politics – but through technology; not through a revolutionary, but through an inventor,” announced Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, a cultural philosopher and visionary, in his book “Practical Idealism. Aristocracy-Technology-Pacifism” in 1925.13 The same view was expressed by Moholy-Nagy in “Painting Photography Film” in the same year: “The engineer has the machine in his hands,” he writes, “satisfying immediate needs. But basically much more: he is the initiator of the new stratum of society, the paver of the way for the future”.14 It was against this background that for many a theorist the photographer was the very embodiment of the Constructivist ideal of the artist-engineer.

Ilse Bing’s self-portrait shows the photographer at once fascinated by her rôle as an artist-engineer and reticent about it. The photograph does in fact contain two self-portraits. Whilst the image within the image portrays her in the pose of a land surveyor standing behind her measuring apparatus, her pose in the foreground is that of the photographer glancing over the top of her camera. This slightly aloof posture prevents the eye from becoming totally identifiable with the camera lens. One might of course explain this by saying that it is a typical feminine attitude towards technology, but this would be too generalizing an explanation, for during the 1920s there were men photographers who embraced a similar approach to technology and there were women photographers who were prepared to identify themselves with it without reserve. Whilst in Germaine Krull’s “Self-portrait with Ikarette” the camera takes the place of the photographer’s eyes, the Berlin photographer and Bauhaus student Umbo holds his Leica so far away from his eyes in his famous self-portrait on the beach taken around 1930 that only its shadow is cast on them. Otto Umbehr, alias Umbo, the portrait photographer and “mirror” of Berlin’s most famous “garçonne” of 1927/28, the actress and writer Ruth Landshoff, was convinced both of the bisexuality of the artistic temperament15 and of the fact that the “camera lies. Its lens is not objective”16. Evidently there were “masculine female photographers” as well as “feminine male photographers” in the 1920s, too.

Lotte Jacobi, « Autoportrait » , 1937, Fotografische Sammlung im Museum Folkwang, Essen © The Lotte Jacobi Collection

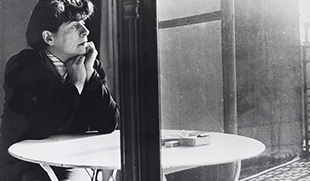

Compared with Ilse Bing’s artistically staged self-portrait, the photograph which the great portrait photographer Lotte Jacobi took of herself in New York in 1937 is almost like a snapshot. An elegant, self-aware young woman, holding her Leica at shoulder height, looks at herself searchingly in an oval dressing mirror. She is wearing a jaunty hat, as if she is just about to go out and is giving her appearance a final once-over prior to facing the public gaze. The momentariness of her pose and the cropped mirror lend the photograph an ephemeral quality. Jacobi’s self-portrait with her bobbed “flapper” hairstyle and the cigarette in her hand is reminiscent of her most famous photograph of the “New Woman”, namely her portrait of the actress Lotte Lenya of 1928, except that this photograph of herself has an additional, self-interrogating aspect. Indeed, this aspect has a twofold presence in the photograph. As though echoing the large reflection in the mirror, the photographer appears as a second, barely perceptible reflection in the bevelled edge of the mirror. She seems to be stepping back and viewing herself from behind. Is she perhaps still not quite sure about her appearance?

The dialectic of private inside world and public outside world also characterizes the self-portrait which the former Bauhaus student, journalist and photographer Ré Soupault made of herself in Tunis around the mid-1930s. What at first glance seems to be the shopwindow reflection of a woman reading a bulletin of the “Dépêche tunisienne”17 is in fact a complex montage produced with the aid of three negatives. A whole series of variants of this portrait – which have survived in the photographer’s estate18 – show Ré Soupault in various poses and garments, with and without cigarette, in her apartment in Tunis. Here Ré Soupault poses before the camera in her private inside world and projects her ideal image of herself – with bobbed hairstyle, culottes and cigarette, the trappings of the emancipated woman – to the public outside world by using a second negative in order to print in a page of the “Dépêche tunisienne”, conveying the impression that she is looking up at it and reading it. The open door on the left-hand side of the photograph, added by means of a third negative, serves as the link between the private inside world and the public outside world. To our knowledge, neither Jacobi’s nor Soupault’s self-portrait was published at the time of its taking and evidently served purely the private purpose of self-interrogation and self-assurance concerning the photographer’s own public image.

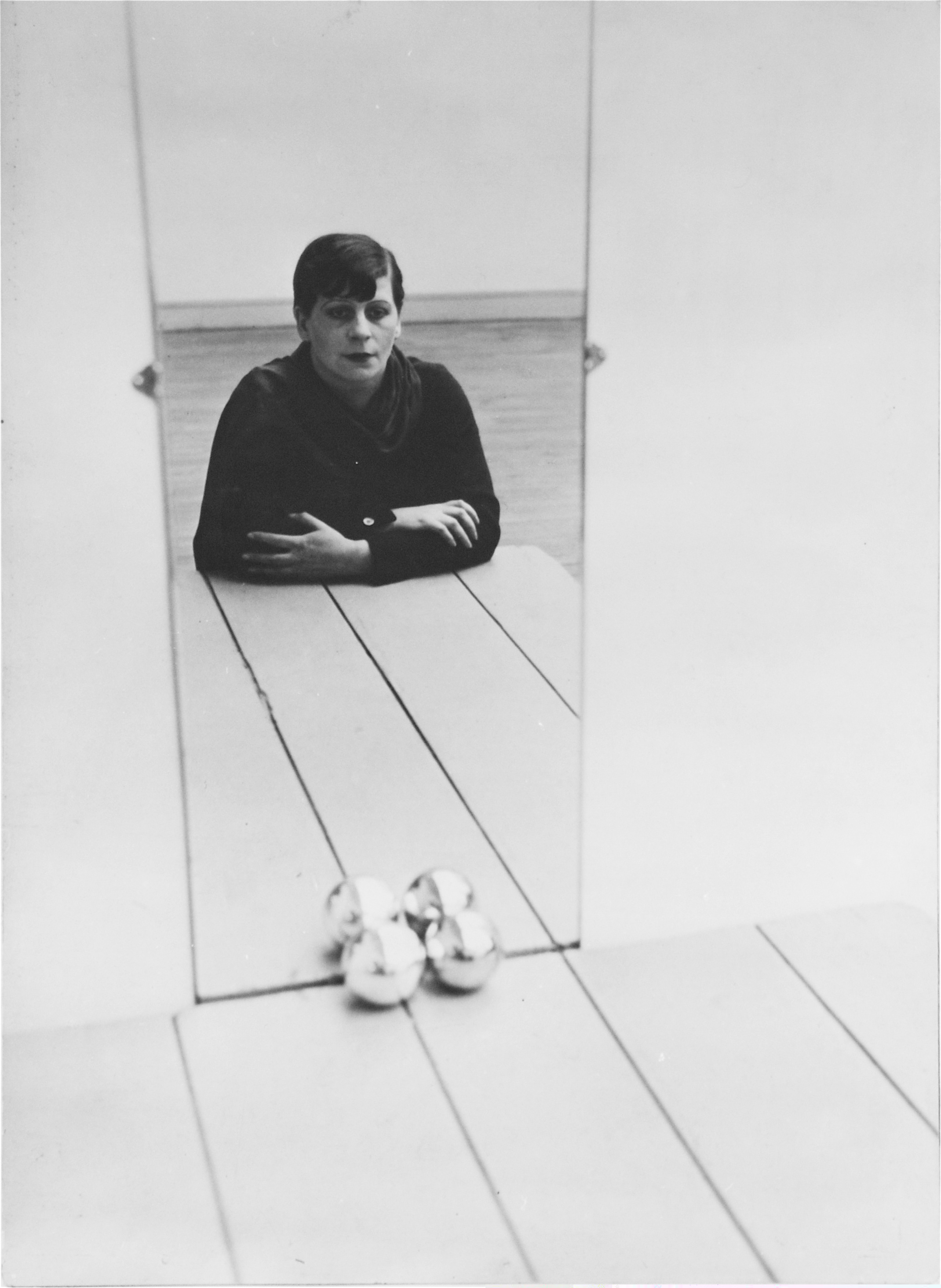

Florence Henri, « Selbstporträt » , 1928, Neuabzug 1974, Archiv Florence Henri, Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genua © Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa, Italy

The paintress and photographer Florence Henri adopted a completely different approach. In her famous self-portrait with mirror and two pétanque balls, taken in 1928, she has photographed herself neither in her private environment nor in her studio nor in a public place, but, rather, in a kind of artificial space, an imagined space which, by reason of its elementary geometrical structure, we recognize as the aesthetic space of abstract Constructivism. It is the aesthetic cosmos of the “Académie Moderne” and the “Bauhaus”, two institutions at which Florence Henri had studied from 1925 until 1927. Whether Henri considered it necessary to use the two mirror-polished silver pétanque balls as symbols of her masculine identity in this male-dominated art world or simply used them as a means of fixing the mirror in place can no longer be factually ascertained. However, Henri’s bisexuality and the fact that she loved having her photograph taken at exhibition previews in trousers and a waiter’s waistcoat with a cigarillo in her hand, even at a very old age, do indeed point to the likelihood that she deliberately integrated these symbols of masculinity in her portrait of herself as an artist. At the time of its taking, Florence Henri was very unsure of her professional identity. She was a trained paintress who was about to change her profession. Thus she portrayed herself neither as a paintress nor as a photographer, but as an artist, as a proud and emancipated woman, her calm and serene bust-like pose awakening associations with the typical depictions of male heroes in classical Renaissance portraiture.

Unlike the self-portraits of Ré Soupault and Lotte Jacobi, Florence Henri’s self-portrait was intended for publication. What was so appealing about the photographer’s profession for the women and, in particular, paintresses of the 1920s was the chance of making their mark in public life. In a most revealing letter written at the beginning of 1928, Henri informs her friend Lou Scheper in Berlin that she is about to give up painting in favour of photography: “I am so fed up with all this vague painting into nothingness, and I have so many ideas for photos. […] I should so much like to have a profession which produces results that also awaken the interest of others”.19 And her work in photography did indeed attract attention very quickly. Her self-portrait with mirror and pétanque balls, taking up a whole page in the most famous anthology of “New Photography”, namely Foto-Auge, a photography book published in three languages by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold in 1929, was henceforth a source of inspiration for all women photographers.

Florence Henri had discovered the mirror and photography at the same time. Indeed, for her the mirror was part and parcel of the photographic challenge she was now taking up. Almost all of her photographs from 1928, her first year as a photographer, are compositions in or with mirrors. The mirror was, as it were, both form and content. Its material flatness on the one hand and its suggestion of unfathomable depth on the other made the mirror and the mirrored image the ideal optical elements for use in photography as a means of evoking the typical complexity and multi-facettedness of post-Cubism, the style of painting in which Florence Henri had been trained. In many of Henri’s photographic compositions, mirrored images and directly photographed or collaged images are interchangeable, the former being easily confusable with the latter and vice versa – as in Henri’s self-portrait of 1938.

Ergy Landau, « Autoportrait » , 1932, Collection APH, Courtesy C. Bouqueret, Paris © Ergy Landau / Rapho

From 1930 onwards, Florence Henri stood out as a specialist in objective, modern women’s portraiture. She did not shy away from nude depictions either, a purely male domain for the past thousands of years. From 1933 until 1939, she regularly supplied the erotic magazines “Paris Magazine”20 and “Paris Sex Appeal”21 with photographs of female nudes. This activity was one which Henri shared with Ergy Landau22, a Hungarian photographer working in Paris since 1923 and one of two women photographers who, in 1933, had succeeded in being accepted into the midst of the male photographers at the “Premier Salon international du nu photographique” in Paris.23 It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in 1932 Landau had already portrayed herself as a nude photographer. The photograph is obviously a very carefully prepared mise en scène, photographed by an assistant and following in the “painter and model” tradition. What is particularly striking about this photograph is that the photographer not only quite literally puts herself on the same level as the female model but also turns her face away from the camera. Unlike her male counterparts in this traditionally male genre of photography, the nude model in this photograph is not a passive object that subjects itself to the active, determining male gaze but rather a partner who not only enters into a visual dialogue with the photographer but also takes an active and determining part in the mise en scène. At the very moment the photograph is taken, the viewer’s gaze is made to perform a peculiar turn of direction, for just as the photographer is focussing her camera on the naked body of the model in front of her, the latter appears blurred in the photograph, while the dressed body of the photographer is absolutely sharp. Was it the photographer’s wish to remain anonymous when photographing another person in the nude – Florence Henri, for example, always spoke of her nude photographs in “Paris Sex Appeal” with a certain embarrassment, but somewhat coquettishly all the same – or was it her intention to liberate the scene from all sexual connotations and merely document it as a working situation which obliged her to turn her back on the camera?

Marianne Breslauer, « Die Fotografin » , 1933, Fotostiftung Schweiz, Marianne Breslauer Archiv © Marianne Breslauer Archiv/Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Quite different, to say the least, was Marianne Breslauer, a trained photographer like Ergy Landau and Germaine Krull. In a self-portrait taken in 1933, undoubtedly the most erotic self-portrait of a woman photographer of the 1920s and 1930s, this Berlin photographer poses, with her cable release in her hand, as a young woman obviously skilful at the game of concealing and revealing. She has deliberately opened her fashionable, fur-trimmed housecoat in order to view her beautiful naked body on the ground-glass screen of the camera. As she is standing to one side of the mirror, her face is hidden by her hair, heightening still further the subtle eroticism of this photograph. Her gaze into the viewfinder of the camera, as though refusing to look herself and, by the same token, the imagined viewer in the eye as she performs her exhibitionist act, seems modest and outdated compared with the erotic self-portraits of women photographers today.24 At once narcissistic and voyeuristic, this self-portrait is less an occupational portrait of the kind intended for publication – we know of no publication of this photograph prior to 197925 – than a private study of a young woman photographer using her professional skills to explore, and take delight in, the eroticism of her appearance.

Although the shadow has a significant part to play in the mythical origins of drawing and painting – according to Pliny, it was the Greek potter Butades who created the first portrait bust after his daughter had traced the shadow of her lover’s face on the wall (“Naturalis historia”)26 -, it did not figure at all in the photography of the 19th century. It was not until the inception of photographic modernism, which evolved from the awareness of its autonomy, that photography discovered the shadow as the very essence of the photographic image – hence the enormous number of shadow photographs during the 1920s and 1930s. With the development of the technique of cameraless photography, the white, “negative” silhouette became an autonomous form of artistic expression (“Rayographs” by Man Ray and “photograms” by László Moholy-Nagy). The photographic print itself may be compared to a shadow, for it unites the dialectic of presence and absence. Indeed, is it not the photograph, this modern expression of permanence resulting from an exposure of but a fleeting moment, which has something just as ephemeral about it as a shadow? With just a few exceptions, all the photographers of modernism, men and women alike, have photographed themselves as shadows. One of the first was Alfred Stieglitz, who captured his and a friend’s shadow on the surface of a stretch of water in 1916. Lucia Moholy, Ilse Bing27 and Imogen Cunningham likewise photographed themselves as projected shadows. In one of Gisèle Freund’s earliest self-portraits, taken in 1929, her face blends with the shadow of a friend28; Lucia Moholy merged her face with that of her husband László Moholy-Nagy to form one single silhouette in a photogram made in 1926.29

Imogen Cunningham, « Self-Portrait, Grass Valley 2 » , 1946 © 1946, 2011 The Imogen Cunningham Trust / www.imogencunningham.com

Shadow portraits cannot be interpreted purely in terms of their media-reflexivity as works of modernism, for they have an iconological significance, too. From time immemorial, the shadow has been a symbol of death – in the kingdom of the dead, for example, human beings live on as shadows. And where are we confronted by our own fragility and transience more impressively than in the permanent awareness of our own shadow? “The peculiar and deeply moving aspect of shadow pictures lies purely in the emotional […]. In its purest form it mirrors the dematerialized world of daydreams, the fine line between appearance and reality; it is, in its true sense, romantic”.30

The 1920s are the decade of masquerade in the history of modern art. Was it the coming of the cinema, that “Hades of the Living”, in which the protagonists forever assume new identities and “the shadows already become immortal while still alive”31, or was it first and foremost the psychological consequences of the profound social changes following the First World War which made masks, disguises and rôle-playing the favourite means of self-stylization and self-discovery among artists and writers of both sexes? For the psychoanalyst Joan Rivière, masquerade was one of the essential features of womanliness, which – she wrote in 1929 – “could be assumed and worn as a mask”, both to hide the possession of masculinity and to avert the reprisals expected if she was found to possess it. […] The reader may now ask how I define womanliness or where I draw the line between genuine womanliness and the ‘masquerade’. My suggestion is not, however, that there is any such difference; whether radical or superficial, they are the same thing”.32 Gender rôle-playing, hitherto reserved in the 19th century for the very close circles of male-attired lesbians, became a fashion phenomenon with the arrival of the “garçonne” in the 1920s.33 The poetess Else Lasker-Schüler, who would frequently masquerade as the Prince of Thebes in the literary cafés of Berlin, was written about as follows: “Disguise was an aid to becoming a person. It symbolizes the ego in the process of either developing or disintegrating. […] Disguise is both the secret and the prediction of a person who seeks himself or herself in the game of (mis)taken identities; one who is versatile in the art of transformation, who can condense into many different persons again and again, but never into a tangible personality”.34 Thus photography was the ideal means of objectifying these transformations and of viewing one’s other self from a distance.

In 1930, Gertrud Arndt, a Bauhaus-taught weaver and textile designer, took forty-three portraits of herself in only a few days. Adopting a style which was in direct contrast with the functional Bauhaus aesthetic – indeed, it was a “welcome break” from it35 –, Arndt slipped into the rôles of different eras and cultural circles and captured these mises en scène with her camera. They were private photographs, photographs intended purely as a means of coming to terms with her own self, not for publication.

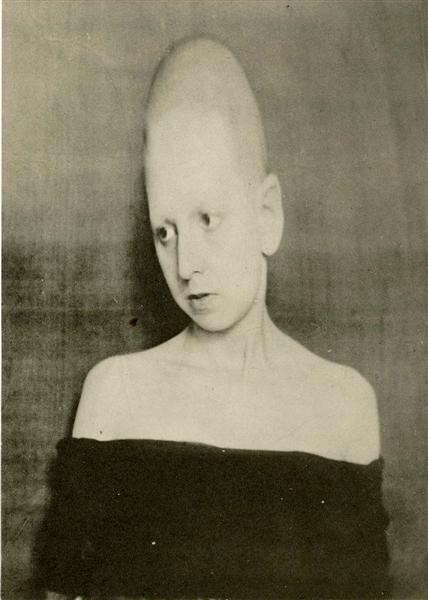

Likewise private and personal were the photographic self-estrangements which the authoress Claude Cahun staged with the help of her life-long companion Suzanne Malherbe between the years of 1917 and approximately 1939. Claude Cahun did not see herself as a photographer – only two of her meanwhile famous self-portraits were published at the time – but rather as a writer and intellectual. As a woman and lesbian in a patriarchal world of art and literature and as a Jewess and radical socialist in a capitalist and anti-Semitic society, Claude Cahun contradicted the official notion of womanhood in so many different ways that her work essentially became a form of literary, theatrical and photographic introspection, a means of constantly reassuring herself of her identity. Immediately she began to experiment with her appearance in her self-portraits, she changed her name. Adopting the name of a great uncle, the young girl Lucy Schwob had now become the genderless Claude Cahun. Her self-portraits with shaven head, taken in 1928, were distressingly radical (she herself called them her “monstrosities”), exaggerating, for example, her Jewish physiognomy or anamorphously deforming her head so as to appear cretinous. This last-mentioned photograph was published with the title “Frontière humaine” in the avant-garde magazine “Bifur” in 193036.

Claude Cahun, « Frontière humaine », publiée dans la revue « Bifur » , n°5, avril 1930

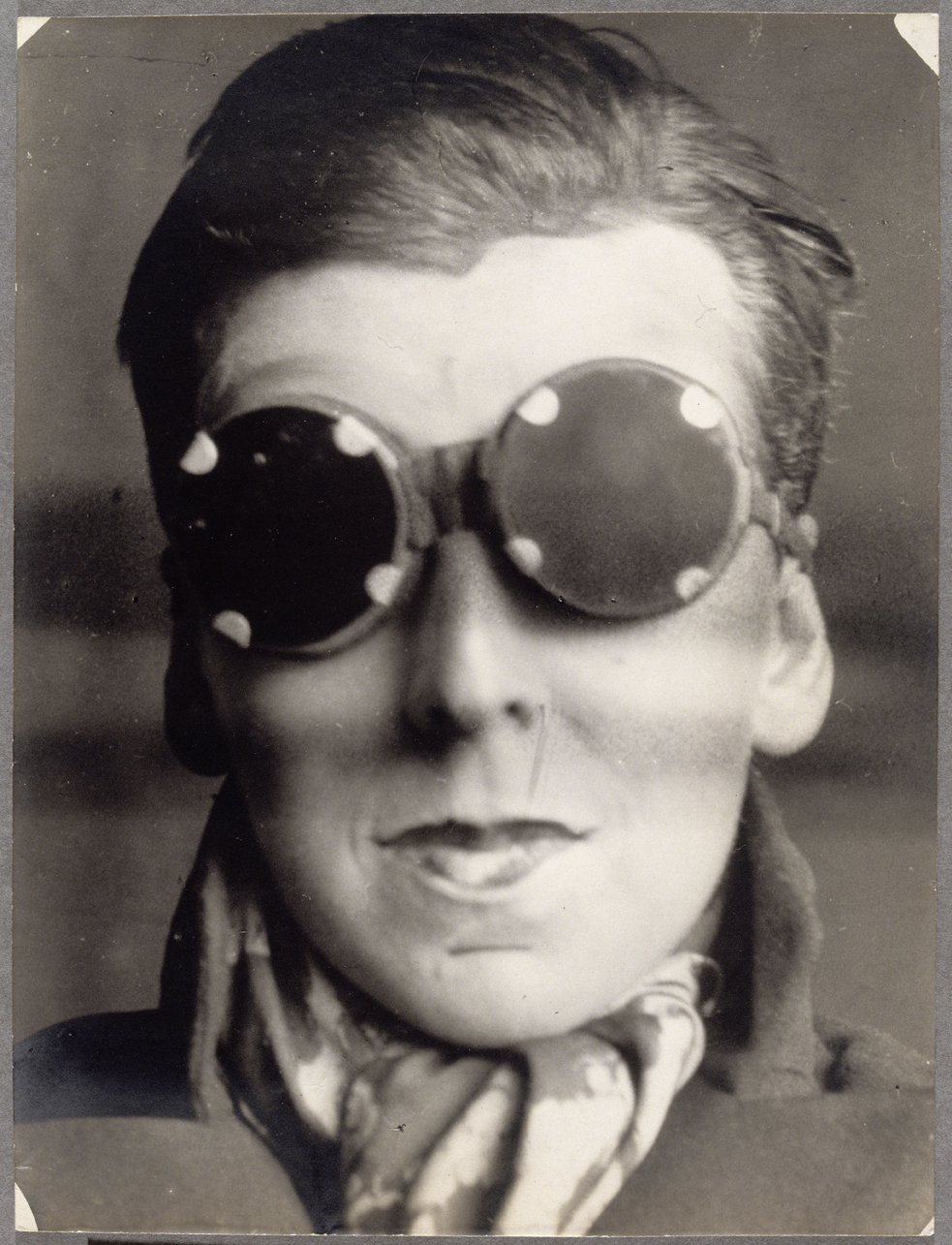

No other woman photographer of the 1920s ever transcended the boundaries of her own identity as actionistically as Claude Cahun. Deeply rooted in the literary aesthetic of the fin de siècle, Cahun lived the life of a female dandy in the literary and lesbian milieu of Paris. Convinced of the theatricality of life – “The happiest moments of your whole life? Dreaming. Imagining being different. Playing my favourite rôle.”37; in 1936 she joined a theatrical group – making her own body the stage for her transgender masquerades. It is in her self-portraits, staged with the help of her life-long companion Suzanne Malherbe, that Claude Cahun confronts us – entirely in the sense of Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” – as a seductive young sailor, as a harlequin in front of the mirror, as Faust’s Gretchen, as an attractive lesbian with face mask, as a garçonne with motorcycle goggles, as Buddha, as a pucker-lipped weightlifter in a woman’s costume with painted-on nipples or as an actress wearing a cloak covered with masks. Claude Cahun clearly endeavoured to realize that same “poetical evidence” which she had always sought as a poetess in her real life, too, and, with the aid of her photographs, to prove to her few like-minded friends “that there is no dualism between imagination and reality; on the contrary, everything the human mind can design and create flows from the same veins and is made of the same stuff as his flesh, his blood and the world that surrounds him”.38 “Je veux changer de peau: arrache-moi la vieille,” she writes as the chapter heading for the year 1928 in her autobiographical work “Aveux non avenus”.39 In creating a multiplicity of male and female identities, Claude Cahun sought to achieve a kind of sexual ambivalence of her own self, a transfiguration of the clichés of hetero-, homo- and bisexuality: “Confuse people. Masculine? Feminine? But that all depends on the case. Neutral is the only gender which always suits me.”40 Behind all these ego variables, however, lies the despairing experience of not actually having a gender and a self of one’s own. “Under each mask a face – I shall not succeed in revealing all these faces,” she writes on one of the collages of a dozen of her faces in “Aveux non avenus”.41 “I try in vain to put my body back in its place (my body with all its dependences), to see myself in the third person. My self is imprisoned in myself like the e in the o.”42 It was photography which enabled her to see herself from the distance of the third person, for she could now objectify her masquerades in photographs, the testificatory function of which vouched for the fact that what they showed was in fact real.

Cahun’s counterpart among male artists was Marcel Duchamp. What their very different artistic temperaments had in common was, besides their poetical approach to life, their narcissism, their admiration for the philosopher Max Stirner (“The Ego and Its Own”)43 – or, to use Cahun’s words: “absolute egoism”44. “Tu m’ ”, painted in New York in 1918, was Duchamp’s last painting. Having been a painter since the age of fifteen and now only just thirty, Duchamp had lost his professional perspective and, by the same token, his artistic identity. This identity crisis led to a series of self-displays which he would get his friends – mainly Man Ray – to photograph. Thus, instead of painting his fantasies on canvas, Duchamp now realized them on his own body. He himself had now become an “image” in the public domain, so to speak. Between 1919 and 1921 he presented himself in many guises, once as a “juif errant”45, another time as a monk and “enfant-phare” with a comet-shaped tonsure shaved on the crown of his head46. However, the identity which he ultimately assumed as his public alter ego for the next twenty years was that of a woman named Rrose Sélavy. This name first appeared as that of a copyright proprietress on the model of a window built for Duchamp by a cabinetmaker in New York in 192047. This window to the outside world, the paradigm of European painting since the Renaissance, Leonardo’s “parete di vetro”, is blacked out. Sheets of black leather take the place of panes of glass, obscuring our view of a different world, the world of the imagination. Painting, Duchamp’s former love, is at an end and they must part. Characteristically playing on words, Duchamp calls this work “Fresh Widow”, and its authoress is Rose Sélavy.48 A year later, this ominous artist made her appearance in the guise of a seductive young woman with the facial features of Marcel Duchamp in a photograph taken by Man Ray. It was the heyday of DADA, a movement which provided a ready yet only very small and selected audience for such gender transgressions. Affixed to the label of a perfume bottle with the promising name of “Belle Haleine – Eau de Voilette”, the photograph graced the cover of Man Ray’s and Marcel Duchamp’s jointly edited magazine “New York Dada”.49 For more than twenty years, the fictitious Rrose Sélavy was the shield behind which Duchamp hid his resignation and his artistic identity crisis. She continued to sign his scanty works until she finally disappeared from the scene in the 1940s. Her last photographic mise en scène was the portrait photograph of an emaciated farmer’s wife which Duchamp substituted for his own portrait in the New York exhibition catalogue “First Papers of Surrealism”.

Neither Claude Cahun nor Marcel Duchamp were professional photographers. She was an authoress, he was a visual artist, both of them obeying Baudelaire’s maxim that the imagination must always take precedence over reality. Duchamp’s game with sexual identities was bound up with his aesthetic of the possible.50 “The figuration of a possible./ (not as the opposite of impossible / nor as related to probable / nor as subordinated to likely)”, he writes in one of his often sibylline notes during the period around 1915, “the possible is only/ a physical ‘caustic’ (vitriol type) / burning up all aesthetics or callistics”51. Whether aesthetic or poetical, both Marcel Duchamp and Claude Cahun had an open way of thinking which gave priority to intellectual inventiveness, to the sheer pleasure of thinking what had never been thought before. If they are nowadays regarded as the most important artists of their day, then it is because at that time, when the discourse on truth and progress in the movements of classical modernism (Futurism, Constructivism, Surrealism) was at its peak52, they were already practising a “post-modern” aesthetic concept based on the constant transcendence of given boundaries, a concept in which dogmas, definitions and limitations counted for nothing, a concept in which the one always revealed itself as the other.

Extrait de « La dona, metamorfosi de la modernitat ». A cura de Gladys Fabre, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona 2004/2005.

Footnotes:

1 Christine Bard: Les Garçonnes. Modes et fantasmes des Années folles, Flammarion, Paris 1998; Julia Drost: La Garçonne. Wandlungen einer literarischen Figur, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2003.

2 Ute Frevert, quoted, in translation, from: Die neue Frau. Ein Alltagsmythos der Zwanziger Jahre, in: Katharina Sykora, Annette Dorgerloh, Doris Noell-Rumpeltes, Ada Raev. (Ed.): Die neue Frau. Herausforderung für die Bildmedien der Zwanziger Jahre, Marburg 1993, p. 15.

3 Cf. Kim Sichel, Germaine Krull. Avantgarde als Abenteuer, Munich 1999, pp. 38-40

4 Ibid., p. 68.

5 Cf. Monika Faber: Selbstfoto, in: Fotografieren hieß teilnehmen. Fotografinnen der Weimarer Republik, exhib. cat. Museum Folkwang Essen 1994, p. 284.

6 Paris, Calavas éditeur.

7 Heinrich Kühn, quoted, in translation, from: Fritz Matthies-Masuren: Die künstlerische Photographie, Bielefeld and Leipzig 1922, p. 60

8 Some women photographers also photographed themselves in this manner. Cf. Margaret Watkins, Selfportrait in Headlamp, Paris 1931, in: Sam Stourdzé: Regard Captif. Collection Ordónez/Falcon, Ed. Léo Scheer, Paris 2002, p. 92, and Marianne Brandt, Selbstporträt in der Kugel gespiegelt, Bauhaus Dessau, circa 1928/29, in exhib. cat. Karo Dame. Konstruktive, Konkrete und Radikale Kunst von Frauen von 1914 bis heute, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau 1995, p. 217.

9 Examples of such complex representations are to be found above all in portrait paintings of the 17th century. Cf. Johannes Gumpp’s self-portrait of 1646, illustrated in: Pascal Bonafoux, Der Maler im Selbstbildnis, Geneva 1985, p. 22.

10 Even in the very early days of photography, the metaphorical equation of the photographic and the mirrored image inspired many photographers to incorporate in their works mirrored images of persons viewed from a different perspective. Cf. the portrait of an unknown daguerreotypist dating from around 1855 in: Sam Stourdzé: Regard Captif. op. cit. (Note 7), p. 150.

11 Cf. Hermann Schnauss: Fotografischer Zeitvertreib, Düsseldorf 1899, pp. 57-72 and pp. 113-116; Alfred Parzer-Muehlbacher: Fotografisches Unterhaltungsbuch, Berlin3 1910, pp. 111-112 and pp. 132-141.

12 Charles Chaplot: La photographie récréative et fantaisiste, Paris2 circa 1908, pp. 102-123.

13 Quoted, in translation, from: Praktischer Idealismus. Adel-Technik-Pazifismus, Vienna and Leipzig 1925, p. 105.

14 Quoted, in translation, from Malerei Fotografie Film, Albert Langen Verlag, Munich 1925, p. 30.

15 Cf. Herbert Molderings: Umbo. Otto Umbehr 1902-1980, Düsseldorf 1996, p. 34.

16 Ibid., p. 74.

17 The composition of the photograph is reminiscent of Umbo’s “Self-portrait in a shopwindow” of 1927 [cf. Molderings, Umbo, op. cit. (Note14), Plate 46]. Ré Soupault was a close friend of Umbo’s ever since they studied together at the Bauhaus in Weimar between the years of 1921 and 1923.

18 The authors wish to thank Mr. Manfred Metzner of “Das Wunderhorn” publishing house in Heidelberg for having made copies of these photographs available.

19 Quoted, in translation, from Photography at the Bauhaus, edited by Jeannine Fiedler for the Bauhaus-Archiv, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts1990, p. 57, reproduction of the original letter in German.

20 Cf. “Paris Magazine”, August 1933, September and November 1934, April and May 1938, March and April 1939.

21 Cf. “Paris Sex-Appeal”, No. 14, September 1934, back of cover.

22 Cf. “Paris Magazine”, November 1935 and September 1936.

23 Cf. Nus. Daniel Masclet: La Beauté de la femme. Album du Premier Salon international du nu photographique, Paris 1933. – In the anthology Formes nues, published in 1935, there were already seven women among the selected photographers, clearly showing that women photographers had very quickly conquered this male domain of photography. Cf. A. Mentzel / A. Roux: Formes nues, éditions d’art graphique et photographique, Paris 1935.

24 Cf., for example, the self-portraits of Chloe des Lysses on the website www. sweetch.com.

25 Cf. Marianne Breslauer, in the series: Subjektive Fotografie. Edition Marzona, Bielefeld/Düsseldorf 1979, Fig. 1.

26 Cf. Victor I. Stoichita: Eine kurze Geschichte des Schattens, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1999, pp. 11-14.

27 Cf. exhib. cat. Ilse Bing. Fotografien 1929-1956, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aachen 1996, Fig. 2: “Hellerhofsiedlung in Frankfurt – My shadow and the shadow of the architect Mart Stam on the roof”, 1930.

28 Cf. photograph in: Gisèle Freund Berlin-Frankfurt-Paris Fotografien 1929-1962, ed. by Marita Braun-Ruiter, Berlin 1996, p. 12.

29 Cf. Rolf Sachse: Lucia Moholy, Düsseldorf 1985, photograph on p. 69. The indicated date “around 1923” is incorrect. Several head photograms are dated 1926 in László Moholy-Nagy’s handwriting, from which one may safely assume that the head photograms made together with Lucia Moholy were not produced until around 1926 either. For further information on the dating of these photograms cf.: Floris M. Neusüss and Renate Heyne: Werkverzeichnis, in: László Moholy-Nagy Fotogramm 1922-1943, Munich 1996, p. 180.

30 Quoted, in translation, from Ulrich Raulff: Umbrische Figuren. In: Floris M. Neusüss: Fotogramme – die lichtreichen Schatten, Kassel 1983, p. 14.

31 Joseph Roth, quoted, in translation, from Ulrich Raulff: Umbrische Figuren, op. cit. (note 29), p. 16.

32 Joan Rivière: Womanliness as a Masquerade. In: International Journal of Psychoanalysis 10/1929. Quoted from: Hendrik M. Ruitenbeek (Ed.): Psychoanalysis and Female Sexuality, New Haven 1966.

33 Cf. Julia Drost, La Garçonne, op. cit. (Note 1).

34 Quoted, in translation, from Sabina Lessmann: Weiblichkeit ist Maskerade. Verkleidungen und Inszenierungen von Frauen in Fotografien Madame d’Oras, Marta Astfalck-Vietz’ und Olga/Adjoran Wlassics’, in: Sykora, Dorgerloh et al. (Ed.): Die neue Frau, op. cit. (Note 2), pp. 149/150.

35 Quoted, in translation, from Sabine Lessmann: Die Maske des Weiblichen nimmt kuriose Formen an…. Rollenspiele und Verkleidungen in den Fotografien Gertrud Arndts und Marta Astfalck-Vietz’. In: Fotografieren hiess teilnehmen, op. cit. (Note 5), p. 274.

36 No. 5, Paris 30th April 1930, immediately after p. 104.

37 Claude Cahun: Aveux non avenus, Éditions du Carrefour, Paris 1930, p. 66. “Moments les plus heureux de toute votre vie? Le rêve. Imaginer que je suis autre. Me jouer mon rôle préféré.”

38 Paul Eluard: L’évidence poétique. Habitude de la poésie. GLM, Paris 1937, n.p.

39 Aveux non avenus, op.cit. (Note 36), p. 231.

40 Ibid., p. 176. “Brouiller les cartes. Masculin? Féminin? Mais ca dépend des cas. Neutre est le seul genre qui me convienne toujours.”

41 Ibid., illustration preceding p. 113. “Sous ce masque un visage. Je n’en finirai pas de soulever tous ces visages.”

42 Ibid., p. 236. “En vain j’essaye de remettre mon corps à sa place (mon corps avec des dépendances), de me voir à la troisième personne. Le je est en moi comme l’e pris dans l’o.” Here she refers to the inseparably joined letters “œ” (as in l’œuf).

43 Max Stirner: The Ego and Its Own, edited by David Leopold, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995

44 Aveux non avenus, op. cit. (Note 36), p. 117: “L’égoisme absolu est une sécurité. J’y reviendrai souvent”.

45 Cf. Man Ray photographe. Introduction par Jean-Hubert Martin. Philippe Sers, Paris 1981, Fig. 15. The indicated date of “1916″ is doubtful. The photograph was probably taken in New York around 1920.

46 Cf. ibid., Fig. 16. The correct date of this photograph cannot be reliably ascertained. Duchamp himself had written “Paris 1919” on one of the original prints bearing Man Ray’s studio stamp. Cf. Arturo Schwarz: The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, II, New York 1997, No. 371. Duchamp was possibly mistaken about the date, and the photograph may not have been taken until 1921, the year of Man Ray’s arrival in Paris. This assumption is also borne out by the fact that Duchamp affixed this photograph, bearing the signature Rrose Sélavy, to Picabia’s oil painting “L’Oeil cacodylate” in 1921.

47 Cf. Schwarz, Complete Works, op. cit. (Note 45), No. 376.

48 On this work, the first name of Rrose Sélavy is still written with just one R.

49 Cf. Schwarz, Complete Works, op. cit (Note 45), No. 390.

50 Cf. Herbert Molderings: Die Fotografie des Möglichen. Von Marcel Duchamp bis Anna und Bernhard Blume. In: Jahrbuch der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste, Bd. 13, Munich 1999, pp. 443-493.

51 Quoted from: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. by Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, New York, Da Capo Press, 1989. p. 73. Cf. also: Marcel Duchamp dans les collections du Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris 2001, pp. 26-29.

52 Cf. Herbert Molderings: Relativism and a Historical Sense: Duchamp in Munich (and Basle …). In: Marcel Duchamp. Edited by the Museum Jean Tinguely Basel, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern-Ruit 2002, pp. 15-21.