lundi 2 mars 2015

Le Jeu de Paume, la Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques, le CAPC-musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, Erin Gleeson, commissaire de la programmation Satellite 8, et l’artiste Arin Rungjang déplorent le vol des 15 œuvres orientales perpétré le dimanche 1er mars 2015 au Musée chinois de l’impératrice du château de Fontainebleau. Ils expriment leur entière solidarité avec Jean-François Hébert, président du château, et l’ensemble du personnel, face à la perte de ces objets de grande qualité, d’une valeur inestimable.

Parmi les pièces dérobées figure une réplique de la couronne du roi Rama IV, offerte par les ambassadeurs de Siam à Napoléon III lors de la visite officielle de 1861. Le hasard fait que cette couronne est le sujet central qu’a choisi, fin 2014, l’artiste thaïlandais Arin Rungjang pour l’installation de son exposition « Mongkut », présentée à la Maison d’Art Bernard Anthonioz de Nogent-sur-Marne du 19 mars au 17 mai.

vendredi 27 février 2015

mercredi 25 février 2015

Here is an excerpt of the audio recording I made with Woralak Sooksawasdi na Ayutthaya, for my second video that will be shown at the Maison d’Art Bernard Anthonioz, Nogent-sur-Marne, France :

« My name is Woralak Sooksawasdi Na Ayutthaya. […]

My grandfather started his little business making Khon masks in around 1943.

My father and I have both inhabited that world ever since we were born.

As I grew up, I saw my grandfather and then my father crafting these objects.

It’s a small family business where we each play a particular role in the creative process.

My grandfather had the main role, he was the decorator and assembler, and controlled the whole production process.

My father was a moulder.

My mother and my grandmother made the papier-mâché, inlaid the stones and prepared the Lak sap.

I was able to pick up all these skills.

My grandfather had a passion for drawing and painting, even if his uncle, who was also his godfather, did not encourage his ambitions.

One day when there was a festival at the Phu Khao Thong temple, my grandfather saw some Khon masks – originals and copies.

That day, he swore that he too would make them and he came back with a copy representing a demon.

To achieve his ambition, he sought to increase his knowledge of this art.

Back in Ayutthaya, he attended traditional Khon dance and mask shows. With the help of his mother, he was able to join a theatre troupe.

Consequently, he was able both to act the characters and have access to the masks in the room where they are all kept.

He performed in Khon plays as an actor, then he repaired the masks.

When certain parts were damaged he repaired them and was reimbursed for his outlay. By working there he was able to absorb that universe and acquire the know-how he needed to make his own masks.

I have always looked up to my grandfather.

He is my hero.

And yet, as a child, I never saw myself becoming an artisan and making Khon masks.

Because I am a woman. »

jeudi 19 février 2015

“History has been put into my work, and all the layers show the significance of each history. The theme is not shown in a linear manner, but in a very random way, so viewers can relate themselves to the history. Not just from a historical aspect taught in school or university, but also from their own personal experiences – one they can relate to as a person.”

mercredi 18 février 2015

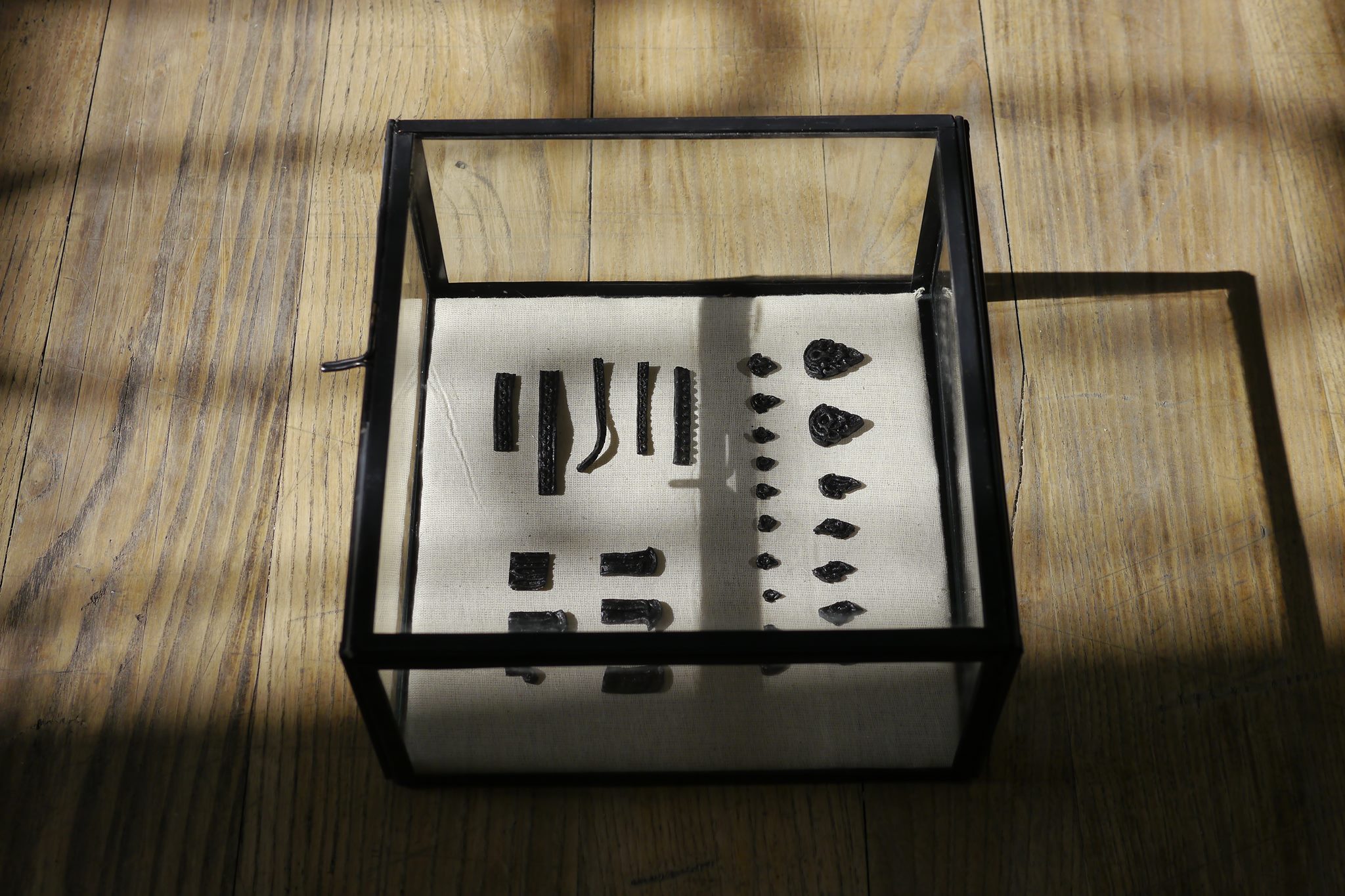

“The second video will be a portrait of Woralak Sooksawasdi na Ayutthaya, King Mongkut’s great, great, great granddaughter. A master craftswoman of theater crowns, she is employed by Thailand’s current queen to propagate royal arts at the Bang Sai Royal Folk Arts and Crafts Centre, north of Bangkok, although her class currently has no students. As Sooksawasdi’s narrative shifts between family genealogy and the declining state of royal craft, the camera explores the studio awash with soft tropical light.[…] In the exhibition, one will find Sooksawasdi’s finished masterpiece, the 2015 replica of the 1861 replica of the original 1782 Chakri Royal Crown of Siam.” Erin Gleeson, curator.

Arin Rungjang, “Mongkut”, 2014, work in progress, documentation, video still. Courtesy of the artist © Arin Rungjang 2015

Arin Rungjang, “Mongkut”, 2014, work in progress, documentation, video still. Courtesy of the artist © Arin Rungjang 2015

mardi 17 février 2015

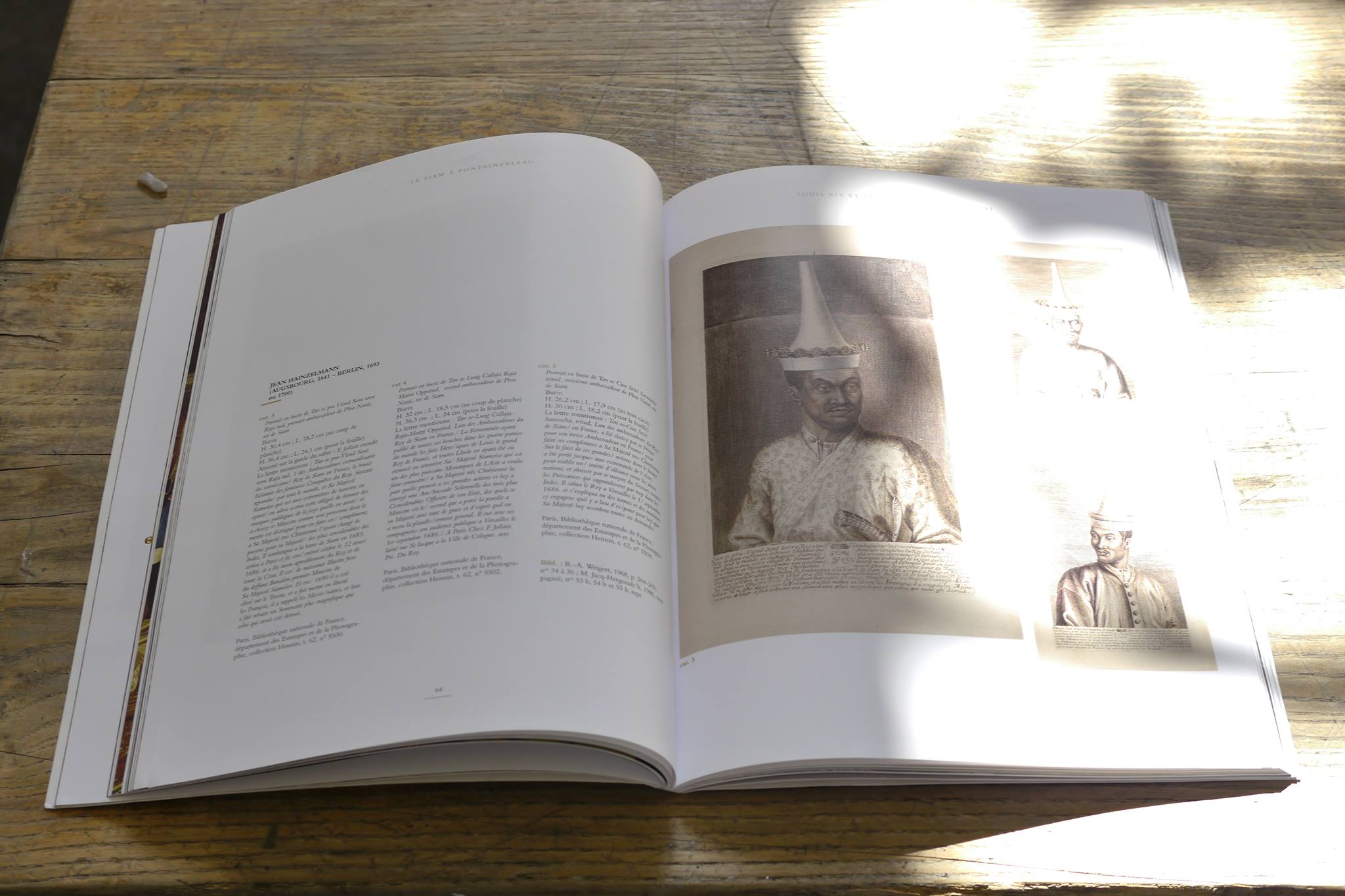

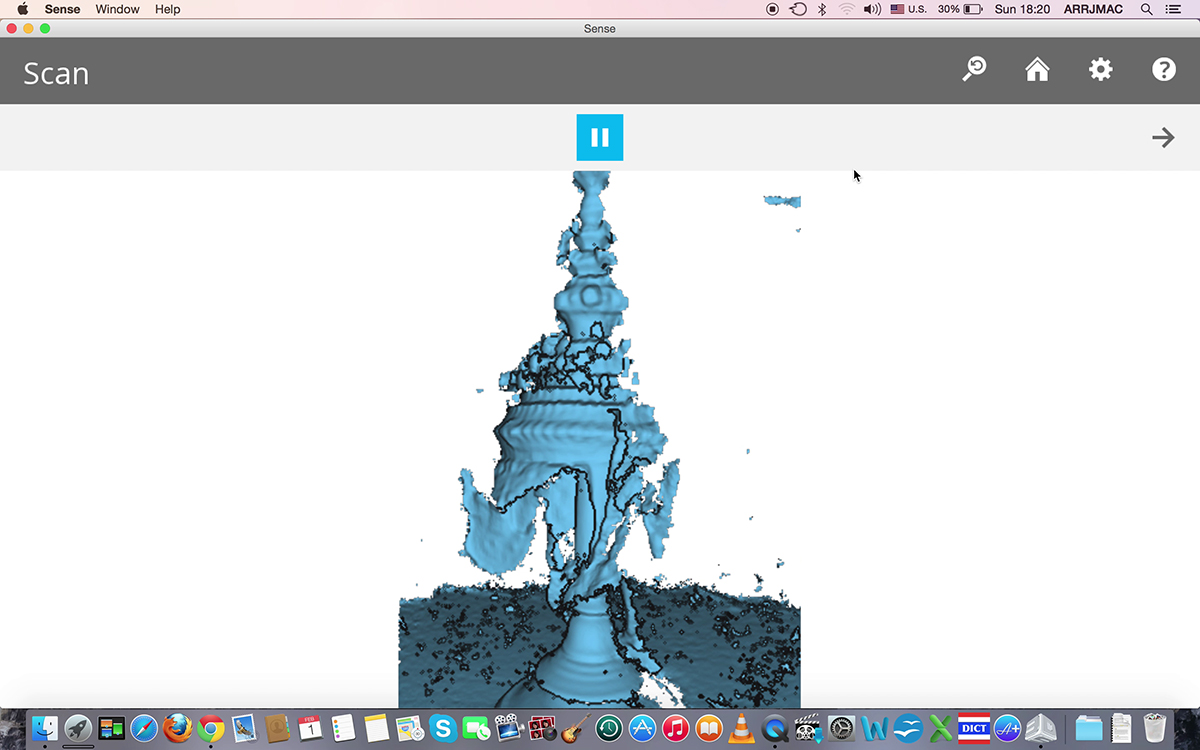

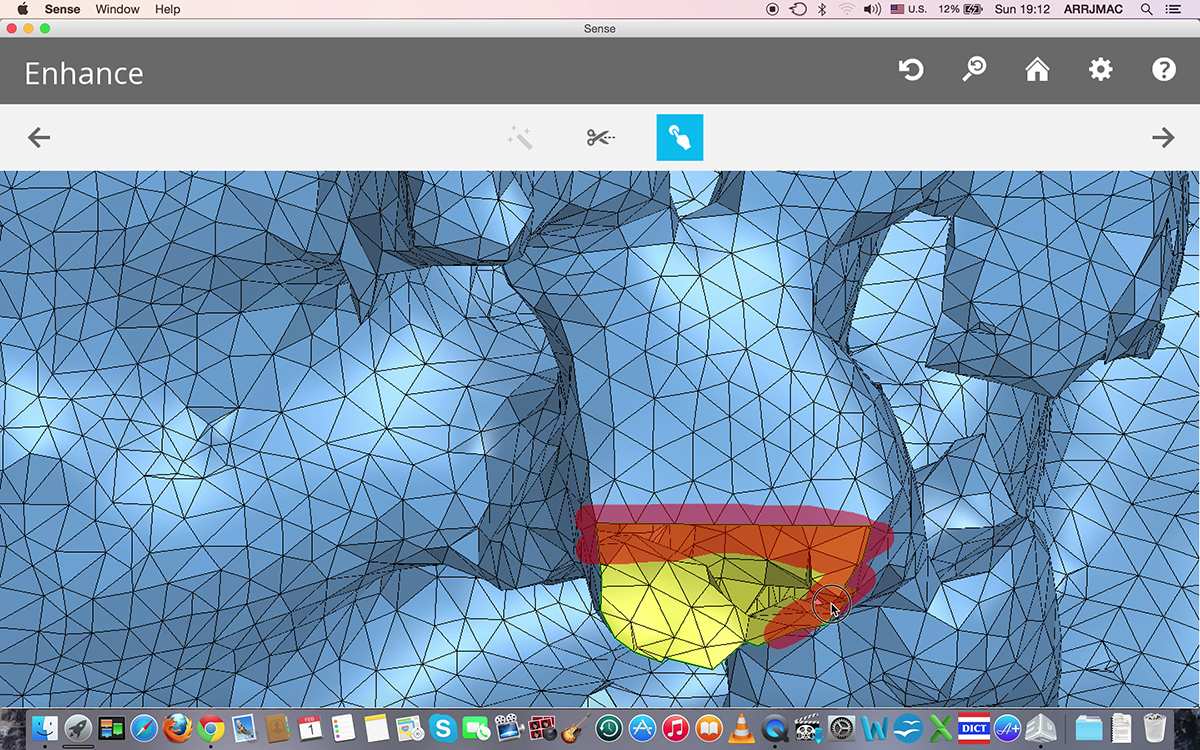

“The first video will present the visually rich mise-en-scène of the château de Fontainebleau in somber winter light, narrated by Pierre Baptiste, renowned curator of Southeast Asian Art at the Musée Guimet. As Baptiste reviews a range of topics from the history of Franco-Thai inter-court relations to the legitimacy of diplomatic offerings and frameworks of display, a young man tours the rooms in solitude, locating the replica in situ, in the drawing rooms of Empress Eugénie, Napoleon III’s wife. Standing at the glass display cabinet, the man casually uses a small, handheld 3D scanner”. Erin Gleeson, curator

Arin Rungjang, “Mongkut”, 2014, work in progress, documentation, video still. Courtesy of the artist © Arin Rungjang 2015

lundi 16 février 2015

“In the eyes of Napoleon III, this embassy enhanced his prestige. Obviously, it confirmed his status as a great European sovereign, receiving the homage of another sovereign from the other side of the earth. […] It is likely that this homage paid to Napoleon III, with great signs of respect—Siamese court protocol dictated that ambassadors should crawl—had a significant impact, because this protocol could give France the illusion that Siam was crawling at the feet of Emperor Napoleon III. But all that is purely symbolic, because from a diplomatic point of view, France never really had any ascendancy over the territory or ruler of Siam. So yes, it’s true that, in spite of it all, there were periods of tension, notably with the question of the retrocession of provinces to Cambodia, that is to say, to French Indochina. Still, at the time of the embassy I think that, in the end, for the Emperor Napoleon III it was a way of dominating the ruler of Siam, even if King Mongkut had not really seen it that way at the time.”

Pierre Baptiste, senior curator of the Musée Guimet, from a conversation with Arin Rungjang, 17 December 2014.

— — —

« Aux yeux de Napoléon III, cette ambassade est un élément de prestige : c’est évident car cela assoit sa stature de grand souverain européen, qui reçoit l’hommage d’un autre souverain se trouvant de l’autre côté de la terre… Il est probable que cet hommage rendu à Napoléon III, qui se fait avec beaucoup d’égards –le protocole de la cours de Siam imposant aux ambassadeurs de ramper par terre– ait eu un impact aussi très important, parce que ce protocole pouvait donner à la France l’illusion que le Siam rampait au pied de l’empereur Napoléon III. Mais tout cela est purement symbolique, puisqu’en fait d’un point de vue diplomatique, la France n’a jamais eu un rôle de véritable domination sur les territoires et le souverain du Siam. Alors c’est vrai que malgré tout, il y a eu des périodes de tension, avec notamment la question de la rétrocession de provinces au Cambodge, c’est-à-dire à l’Indochine française. Mais à l’époque de l’ambassade, je pense que, malgré tout, pour l’Empereur Napoléon III, c’était une manière de dominer le souverain du Siam, même si ça n’avait pas été conçu comme ça par le roi Mongkut à l’origine. »

Pierre Baptiste, conservateur en chef du musée Guimet, extrait d’interview avec Arin Rungjang, 17 décembre 2014.