The territory explored by American artist Brea Souders is her own memory. In this series, she explores a material that was left sleeping in drawers – her own photographic archive – and subjects it to a radical metamorphosis.

Raphaëlle Stopin From your early work onwards, you have been exploring the memory of your family, and your own memories and inheritance. How did you reach this point, embodied by Film Electric, of exploring that same subject but with the help of the very foundation of the medium, the original?

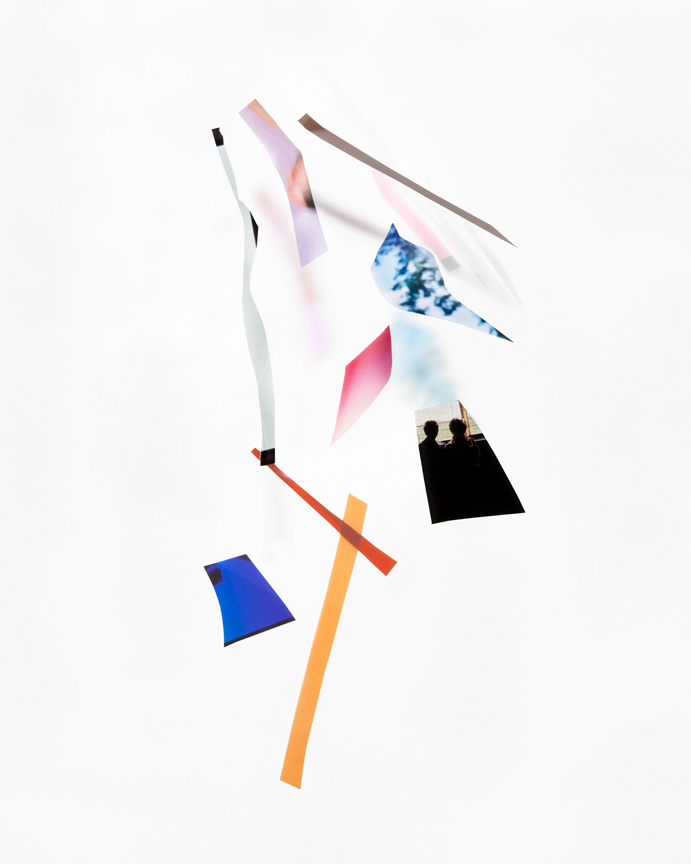

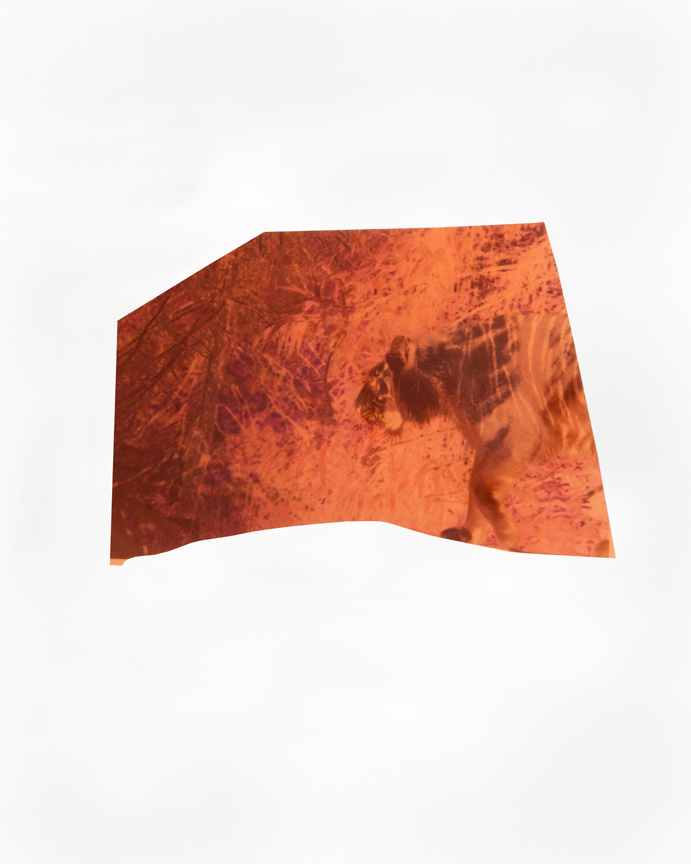

Brea Souders I explore various concepts in my work, memory being one of them. With Film Electric, I am not so much interested in my own specific memories, but in the nature of memory itself. I happened upon this project accidentally, as I was cutting up old negatives from my archive. This archive spanned the past ten-plus years and there were many negatives that I knew I’d never use to make a print – negatives that were too light or dark, a blurry face, an awkward composition, strange colour shifts. The archive contained a true cross-section of my life – family vacations, pictures of loved ones and strangers, pets, plants, experiments, art projects, poetic musings, images of nothingness, everything. I cut these strips of film over a piece of clear plastic and observed that they clung to the plastic as I went to throw them away. Certain bits clung to the plastic, while others fell away. This invisible force – static electricity – determined what remained and what disappeared. I thought this an apt metaphor for the nature of memory itself. Why do some memories hover in the foreground of our mind, while others fall away? It reminded me of the often fragmented nature of the memories that stay with us – how we’ll remember an entire day in snippets, impressions, feelings half-felt, instead of the full scope of the experience as it was.

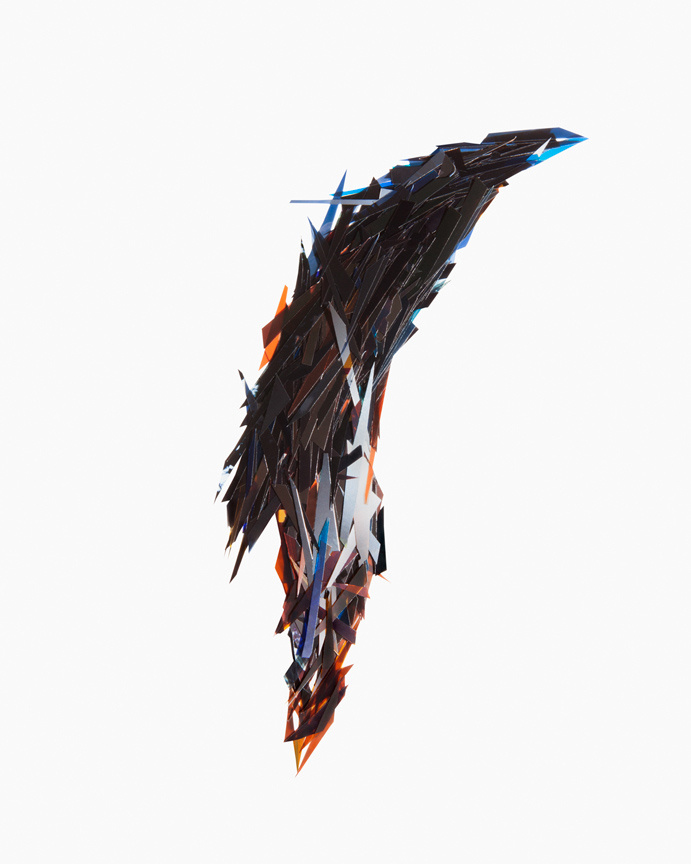

RS Some pieces from Film Electric seem to come out of some sort of vortex, gathering unidentifiable bits and pieces assembled in spiral shapes. It seems like they are all moved by a sense of a common destiny, as if they had understood a common design that they share and express. How did you go about these compositions? Where did these shapes emerge from?

BS The shapes are created by contorting the pieces of clear acetate, by literally bending and twisting them. When the film pieces cling to this material by static force, they don’t enter some kind of immediate stasis. They shift around as I manipulate the acetate. Sometimes the pieces will cluster together, creating a very dense spiral. Other times, most of the pieces will fall off the acetate and it will become a more minimal composition. This result is also affected by how many film pieces I add in the first place, the shape of the acetate, and so on. These decisions are based on how I feel that day and on my commitment to experimenting with forms.

RS You have always shown a great deal of interest and skill in mastering colour in your photos. How did you deal with it for Film Electric?

BS I’ve had to let go and embrace the inherent colour properties of film itself. Since I began shooting film I’ve been drawn to the red cast of negative film and its monochromatic nature. This was my starting point from which I proceeded to mix in slide film which can depict the world in “real” colour. I like when they intertwine in the same image, where real and abstracted colour coexist. Along with the neutral and pale backgrounds, I think the colour is quite striking in this project and I’m happy when those colours come to the foreground by chance. As I’ve said, the film pieces are all from my own archive, so the source material has all been shot with a particular colour palette that I’m drawn to, which is to say that though there is chance involved it’s all within a colour-world of my choosing.

RS What did it change for you, as a photographer used to building an entire new image in front of her camera, to be recycling pictures, and to choose this radical gesture of cutting an image into pieces and letting the compositions go?

Ultimately what image (of your memory and identity) did that lead you to?

BS It was a truly refreshing change of gears. I haven’t stopped building images from scratch, but the gesture of cutting my archive up has served as a release valve of sorts. Old work breathing fresh air into my process. It’s interesting to know exactly what methodology I will be working in when I enter the studio each day. I had hit a point in my work where I needed a mental break and to let go of myself somewhat. Now I’m again building from scratch, and may go back and forth between the two in the future, and who knows what else will come from that dynamic.

Brea Souders’solo show at Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York: June 12th – August 1st 2014

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Brea Souders now lives and works in New York City. She has studied art at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

She has exhibited in many galleries and festivals, notably: Bruce Silverstein Gallery, Abrons Arts Center, the Camera Club of New York and the Center for Photography at Woodstock in New York, as well as the Hyères International Festival of Photography & Fashion, France, the Singapore International Photography Festival and the Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives. She has received a Jean and Louis Dreyfus Foundation fellowship at the Millay Colony of the Arts and a Women in Photography/LTI-Lightside Kodak materials grant. Souders’ work has been featured in New York Magazine, Artnews, and Creative Review.