Raphaëlle Stopin You grew up in the streets of Venice, Italy, perhaps one of the European cities most impermeable to the changes induced by modern times (apart from erosion, not much has changed in the landscape) and you are now based in London, a high-tempo megalopolis. Dalston, a paroxysmal expression of urban activity and its sometimes chaotic atmosphere, is now your home. How did this environment appear to you as a “subject” you wanted to deal with ?

Lorenzo Vitturi Venice has not changed as a landscape but socially the change has been dramatic. In the 60s there were 120,000 Venetians citizens, now there are only 60,000. What has already been happening in Venice for decades, is now happening in most of the major European capitals, where gentrification is profoundly changing their social geography: today only big brands or really rich people can afford to live in city centres, while the rest of the population is forced to the outskirts. The heart of the city is now transformed into a dry and standardised boutique.

Venice is now a Disneyland, a playground for millionaires and tourists, and London too is currently going through a harsh gentrification process, which is painful to see. So I continue to come across these places, and capture something of them as they are, at their rawest and most beautiful, with all their flaws and smells and things-to-be-done-differently, before they too warp and transform and disappear as we know them now, as time moves ever forward.

When I found myself in Dalston four years ago, I did what I always do. I searched for colour and excitement and life and found it all in Ridley Road Market, one of London’s oldest markets and the hub of the surrounding African, Asian and more recently, Latin-American communities. For me, Dalston is very much like Venice – a curious, fantastical cacophony of culture and colour, homes and voices, and again I felt the urge to capture the market, this community and distil it in the form of a photograph.

RS Dalston Anatomy, as a title for the project, implies that you observe, study, or otherwise dissect this body that the market would be: from its main characters – both clients and sellers – to its goods. Which part caught your attention first? Which aspect – of the portraits or still lifes – did you explore first? Does one necessarily induce the other ?

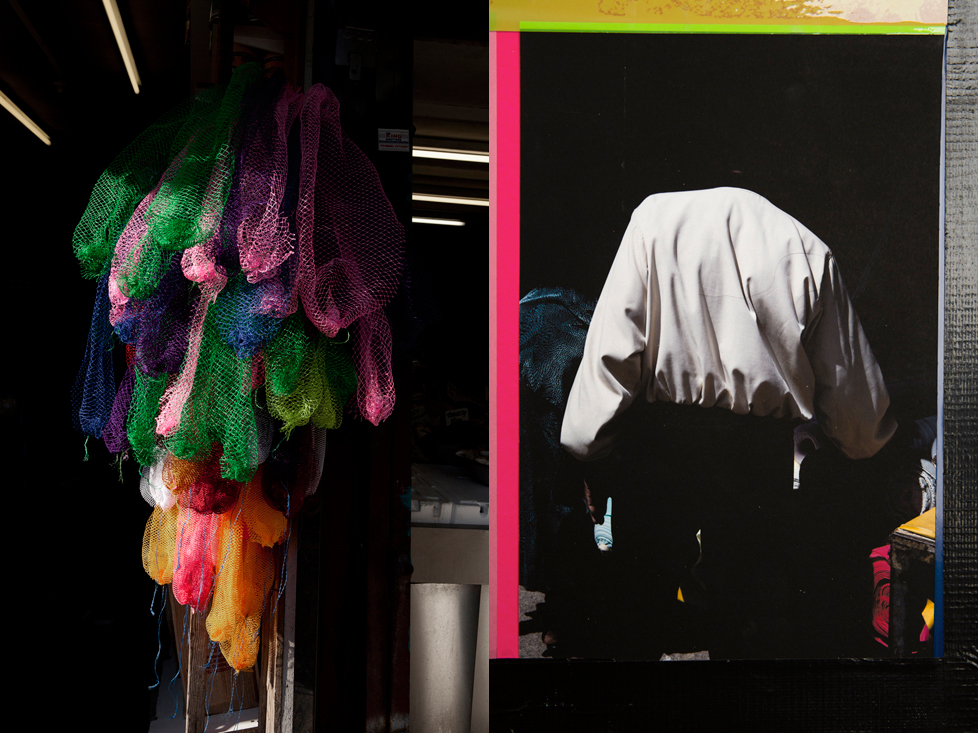

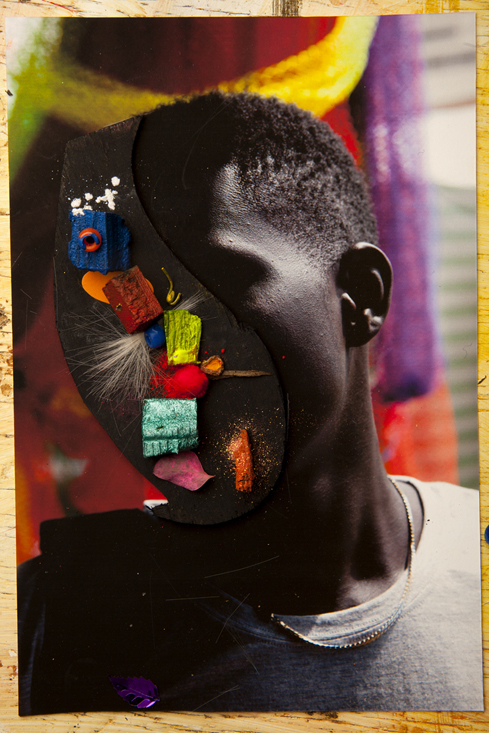

LV I like to compare my process to that of a visionary anatomist. To understand this you have to imagine the market, its products and its people as a whole single body, which I dissect using the camera as a surgeon’s knife and my studio as a laboratory. During the anatomy process I selected the elements/fragments which I thought were more interesting, exclusively in terms of their shape or colour. Following their selection, I brought all these fragments into my studio and I mixed them all together, during a sort of promiscuous game where sculpture, collage and painting melt together, and I recreated a series of new anatomies, whose features only exist in my own visionary world. The final output of the process is a heterogeneous series of images that mix different languages and photographic approaches, from snapshot and portraits taken on the street to photos of sculptures, from photographs of collages to scans of found materials.

RS Those two aspects – portraits and still lifes – echo one another, leading to some fascinating formal parallels, enhanced by your layout. Faces, hairdos, skin, are seen as materials and volumes, to the extent that portraits are sometimes literally taken as a starting point for the creation of another image (you enlarge a portrait you took, to which you apply pigments or other material taken from the market, re-photograph the whole to create a new image). The reality of your environment is then raw material that can be altered, but within your baroque fantasies you manage to create a space for a true document of the market as well. To be able to talk about the spirit of the place, to be somehow in the truth of this environment: was this one of your intentions when you started on this project ?

LV When I started Dalston Anatomy I just felt the instinctive need to freeze everything else that I was doing, to choose the biggest corner of my flat, build a studio corner, just start playing with the objects I could find in the nearby streets of Dalston, mainly debris and products from the market. That’s how everything started really.

For a couple of months I just walked up and down in the market. I selected materials, brought them back to the studio, used them as raw material to build precarious sculptures and photographed them before and after their collapse. Only then did I start asking myself what I was really doing and what was the rationale behind all this work.

I then realised that my neighbourhood was dramatically changing day after day, and its people were changing too, and new people were moving in. I also realised that the debris I was collecting was not just ordinary trash but it was in fact what was left of old flats and lives, parts of those interiors that were being refurbished for the arrival of a new class.

The last revelation was that all these images I was producing were in a way not just the result of my secret imagination but were deeply connected with a wider reality. They were fragments of a bigger picture, my own “bigger picture”, which also clearly includes the place I live in and the community that I love and care for.

RS Dalston Anatomy is primarily a book. Its cover is made with an African textile and when you open it, it feels as dense as Dalston’s streets: full-page images, few borders, very few white pages. Was it obvious to you that the project would be a book before anything else ?

LV From the beginning I knew that the book was one of the best mediums for showing what I had in mind. And from the beginning, throughout the process of collecting images, forging atmospheres, making sculptures, I was in fact already editing the book, and this helped me to find optimal visual coherence between the sculptural side of the work and all the different visual outputs I was coming up with. I treated every double-spread as an empty physical space ready to host a different composition. Everything has been edited together trying to create a fluid series of images using colours and anatomical similarities as a narrative binding agent. A sort of musical rhythm, an Afro beat if you will.

RS You made installations with your photographs in the market and glued posters of them in the market. Some of them were removed and reused by the inhabitants and passers-by. In this way you were placing yourself in this flux of merchandise / goods / exchanges. How do you see yourself, as an artist and citizen, within the frame of your image ?

LV As soon as I finished the project I felt the need to bring the work back to the people and the community of the market (who might be the most photographed people of East London yet never see any pictures of themselves). I wanted to see their reaction and to complete the cycle I began when I started the project. I did not like the idea of using the soul of a community and a place and then closing it off immediately in a gallery to show it only to a selected elite.

I think an artist should have an active role in his community and use his visionary capacity to show things in a different way, and to the widest public possible. By this I mean to say that if we still look at art as a medium for communicating grand concepts, and for reconnecting people to their most visionary ideas, then it is not only museum-goers who should consume art. It is precisely those who are busy shaping our society with their daily work who should be able to see how beautiful and meaningful the product of their work is. I remember one of the market stall-keepers being amazed at the way his vegetables, if just looked at from a different perspective, could turn into a piece of art.

Of course, when one shows an art project to the public, whose main interest is not photography or art, one has to be ready for all sorts of reactions: strong opinions, acceptance and refusal. Luckily the work has been appreciated and the majority of the people enjoyed it and understood Dalston Anatomy as what it is: a visual ode to Dalston, as a unique place where different cultures merge together but also a celebration of life as an expression of diversity and unstoppable energy.

Italian photographer based in London, Lorenzo Vitturi (Venice, 1980) studied photography and design at the Instituto Europeo di Design in Rome and then at the Fabrica research center of Benetton communication. From his previous experience in cinema (he was a painter and decorator), Lorenzo Vitturi has retained a taste for installation and staging.

Dalston Anatomy was selected in 2013 for the “Paris Photo – Aperture Foundation PhotoBook” Awards and simultaneously exposed to 3h FOAM in Amsterdam.

www.lorenzovitturi.com

Second edition of “Dalston Anatomy” by Lorenzo Vitturi

Self Publish Be Happy