On January 2, 1986 Peter Hujar covered the walls of the Gracie Mansion Gallery on 167 Avenue A with a two-image high grid of seventy square medium-format black and white silver-gelatin prints that encompassed landscapes, portraits, ruins, animals, trash, and water. It is recreated in the current Jeu de Paume exhibition. The grid begins with a portrait of Isaac Hayes from 1971 and a portrait of a corpse in the Palermo Catacombs from 1963.

Upon first viewing, Hujar’s arrangement of images from different genres of work provoked questions like why place a skyscraper next to a cow’s head next to a male nude seated on a bed? The resulting juxtapositions appeared unorthodox when understood through typical sequencing practices wherein images connect thematically and are read from left to right. However, with time, the arrangement came to make an odd kind of sense. A viewer was invited to move in and out of the sequence from the macro of the grid to the micro of a print in no particular order. Each movement in and out created new groupings and associations of images. What connected the images together and made the grid so effective was a distinct vision of the entire world mixed up. The grid’s cohesion broke at the far-right end of it with two formally similar images that were paired horizontally: the first, a portrait of a dead bird, wings spread open, Hujar encountered on a beach with David Wojnarowicz, and, the second, a self-portrait in a white undershirt with Hujar’s shoulders in-line with the contours of the bird. The Mansion exhibition gathered Hujar’s fascinations in disparate subjects and stitched their convergence into a statement on how to see the world. The sequencing Hujar employed in the Gracie Mansion show was not his first experimentation with the grid as a mechanism for gathering images across different genres of work into a unified whole.

From 1968 to 1971 Hujar printed forty-four of his photographs in an experimental 23×34” wordless picture-only tabloid called Newspaper. Published by Affinity, Reality, Communication Inc. out of an apartment on 188 Second Avenue in the East Village, early copies lack credits or a list of artists. The apartment, while not noted in the publication, was occupied by Hujar and his then lover, and principle editor of the Newspaper, Steve Lawrence between 1966 and 1973. The tabloid ran for four issues without a title and one issue as Ark before it took on a formal numeration and name as Newspaper in April of 1969 (Fig 1). Newspaper was the product of a coterie that largely revolved around Hujar and a circle of friends which included photographers, painters, musicians, performers, and sculptors. The publication brought together the disparate subjects, interests, and artworks of their Downtown New York arts scene. Through the years, perhaps as a result of the AIDS crisis, the significant loss of the publication’s audience and editorship, and an ephemeral format which resists archiving, Newspaper faded into obscurity. It was not even found in the remains of Hujar’s own archive. In their current state, issues of Newspaper are crumbling, yellowed, and disintegrating under the acidity of the newsprint. To look at an issue is a process which seems a ritual, and it involves the body, and the clearing of a space large enough to hold its full 23×34” dimensions, a thrice unfolding, and the wide arcs an arm makes to flip a page. Every time that ritual ends, a crumble of newsprint is left behind. My personal collection was found in a closet. The publication, albeit forgotten in scholarship, comes at a crucial point in Hujar’s career, and perhaps foreshadows and markedly influences his later sequencing practices like that at the Gracie Mansion exhibition1. In this brief essay I will closely-read the first and last issues of Newspaper as a means to generate a deeper understanding of the publication’s particular aesthetics.

fig. 2 – Double-page presenting an “Environment spread” by Steve Lawrence, in the first issue of Newspaper , April 1969

The first iterations of what would become Newspaper have no title, and likely began appearing in mid-1968. On a form from curator Kynaston McShine asking for details on the Newspaper for the occasion of its inclusion in the 1970 exhibition Information at the Museum of Modern Art, Steve Lawrence notes Newspaper’s first public showing as “Fall 68, on 500 news stands in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles.”2 Across its run, an aesthetic is relatively consistent within the publication. While symbols, motifs, and works by the same artists appear repeatedly, the apparent chief concern for Hujar and Lawrence in arranging the pages of the magazine was that images were brought together from disparate contexts, mixed up, and placed together in a way that forced meaning and correspondence beyond their apparent lack of connection and/or hierarchical distinctions. Thus, the innovation of the publication was in the ways in which it championed a method of chaotic reading of images. The chaos provoked questions about the way humans read and understood images and the news at that present moment in the late 1960s in the context of expanding media, the Vietnam War, and the social and spiritual revolutions of the counterculture.

What unified every issue of the Newspaper throughout its run was the appearance of a grid of found images called the “Environment.” (Fig 1) While Hujar and Lawrence worked out a concept of gridded found images in the early experiments that lead up to the Newspaper, it is with the first issue of Newspaper from April 1969 that the Environment is given full voice and centrality with the first issue’s cover being dedicated to the chaotic found image grid. (Fig 2) With the first issue, the publication’s masthead is designed much like that of a tabloid, and the eye moves from top to bottom to gain information, like the price, number, and date. The typeface is a bold-set modification of Arial. The backpage and colophon offer a yearly subscription of “Six Dollars Per Year.” Two baby monkeys stare at the reader alongside Julia Child, a killer nuclear ant, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a wax figure with wide piercing eyes bearing the cross of Jesus, a kiss, a nude couple embracing, a tattooed woman, and a young woman topless. Images are coming together from disparate sources: National Geographic, Time, PBS, the 1957 film The Deadly Mantis, an advertisement for Transcendental Meditation, perhaps a porn rag. The immediacy of each image creates a sense of overload. Everything is read and seen happening at once, the images read both as individual photographs, but also come together within the whole of the ‘Environment.’

fig. 3 – Tuli Kupferberg, anti-militarist poet and co-founder of The Fugs. Photographs by Peter Hujar, first issue of Newspaper, April 1969

Inside the first issue, unlike in Hujar and Lawrence’s earlier experiments, credits were added to the bottom right hand corner of each page in 10-point font indicating copyright, date, and artist. The issue opens with two unusual, and perhaps commercial, portraits in sequence by Hujar. In one, Tuli Kupferberg of the band The Fugs looks seductively at the camera. In the second, he takes out an hourglass from his shirt pocket, holds it up towards the camera, and laughs at the viewer. (Fig 3) On the pages that follow are two drawings by William Blake, two portraits by Sheyla Baykal, a set of film stills of hyper-futuristic utopian cities credited as “Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive,” (Fig 4) and two collages by Hujar’s lover and friend Joseph Raffaele.

While these are indeed powerful images, the heart of this first issue of Newspaper is the collage at its center by British artist Gerald Laing. (Fig 5) The collage invites interaction, dotted lines instruct the cutting up and defacing of the magazine, the playing of a game in which the objective was to pair each face to the respective ink print of someone’s penis. The game, by way of its sexual nature, is a wonderful remnant and sign of the publication’s intention towards some type of queer coterie. The point of identification between a player and the game’s subjects came from the possibility or past of sexual kinship, relation, or rumor. The story behind Laing’s collage was relayed to me by Subject A – Michael Findlay. He identified the rest of the group as B. Gerard Malanga (poet and Warhol actor); C. Bill Katz; D. Steve Lawrence; E. Gerald Laing (the artist); F. Jack Mitchell (photographer); G. Billy Sullivan (artist); H. Unknown; I. Ronald Winston (heir to Harry Winston jewelers); and K. Bob Pavlik (companion of Jack Mitchell).3 According to Findlay, they were all men who slept with men. In email correspondence with Gerald Malanga about the spread, he mentioned that he never sat for a dickprint nor did he ever see Laing’s spread.4

Following the ink print game is an uncredited portrait of a poodle, itself reminiscent of Hujar’s own portraits of dogs, juxtaposed to another ‘Environment’ arrangement by Steve Lawrence (Fig 6). The top left of the arrangement groups images formally and thematically. They are all of ‘freak’ twins: Siamese twins, legless and armless twins on a bike, two nude women strapped to a machine. Lawrence places the twin images next to two nude men holding and kissing each other. The men kissing are juxtaposed with the mouth of a screaming and violent bear, a magical castle, a head smashed by an anvil, a figure, perhaps the previous, walking into a coffin, and finally the cosmos. The spread could be read in so many ways — indicating a narrative or not — but a message on homosexuality, and its perceived relationship to the idea of ‘freak’ seems evidently conveyed.

The issue’s remaining pages feature another double-page spread by Sheyla Baykal showing a sequence of images of a nude cabaret dancer backstage and performing, likely a precursor to Baykal’s Palm Casino Revue, two drawings by Lucas Samaras, and a drawing by Lawrence’s young friend from Parsons, Elizabeth Staal, juxtaposed to a group portrait by Richard Avedon of a young Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. (Fig 7) The images from the first issue are loud and in line with a psychedelic countercultural fecundity at the foot of the Stonewall Riots: note the screaming Kupferberg portraits by Hujar, the utopianism of the film-stills, Lawrence’s environment spread, the dick-print game, and the evocation of hell by William Blake and his illustrations to Dante’s Inferno. With its first issue, the publication attempts a dynamic between the visual reading of a tabloid newspaper and that of an artists’ magazine. It plays with the idea of artists defacing the currency of the time: consuming the news, shifting and queering the official account, taking the disposable and ephemeral day-to-day nature of the newspaper and raising it into art while simultaneously demystifying the artwork into trash. The play of signifying art as trash and trash as art is something Lawrence and Hujar continue to play with in the publication up to the very end of its run. The tension between the significations of art and trash are brought to full thematization with a set of Polaroids found at the Museum of Modern Art archives.

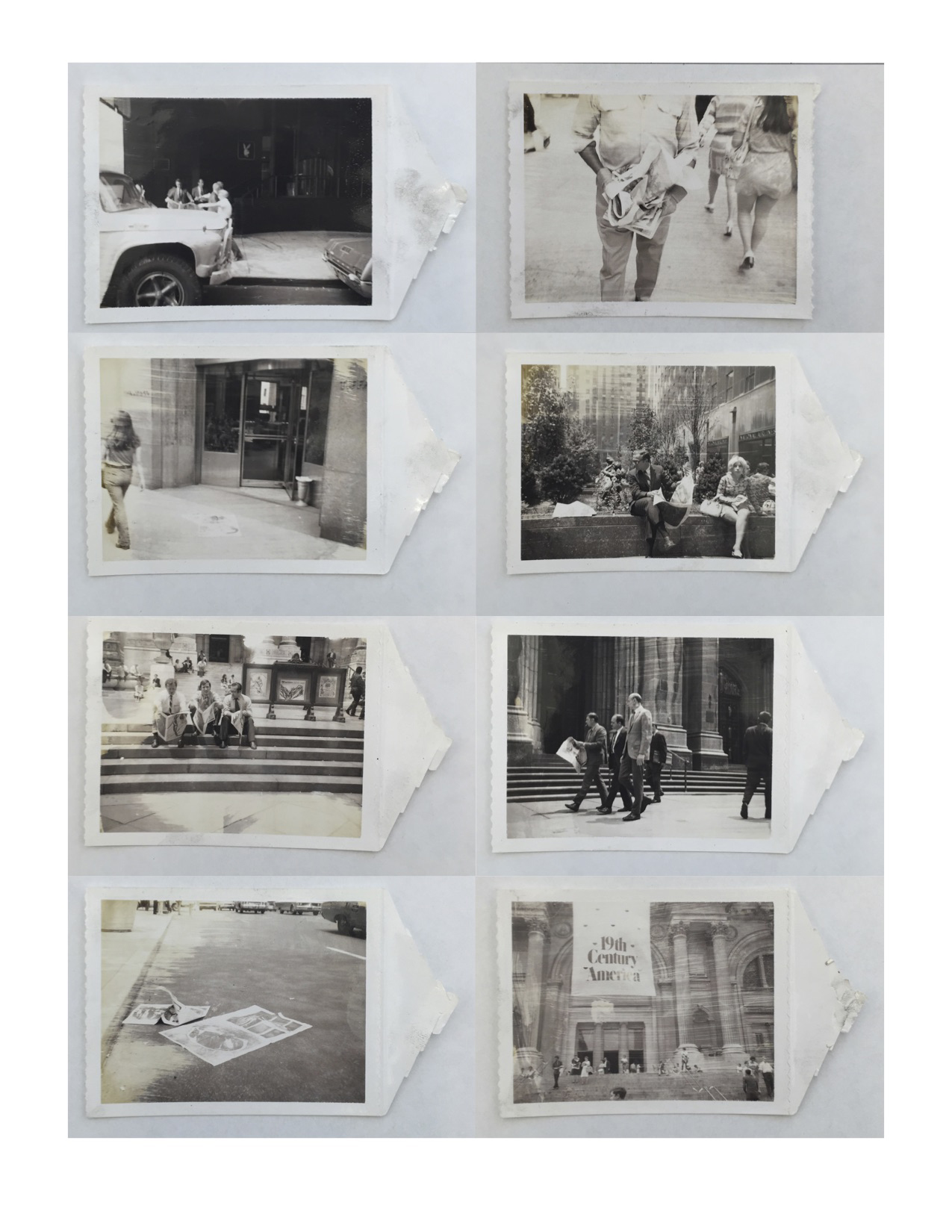

On the file concerning Newspaper at the MoMA archive sits a standard-size yellowed envelope with writing in front stating “April, these are also from Newspaper.”5 Inside are twenty now-fading Polaroids that document an issue of Newspaper as it moves around sections of midtown Manhattan. (Fig 8) The magazine sits by the doors of Tiffany’s, is tossed onto the street, read and held among crowds of Hare Krishnas, crumpled, trashed, and trampled on by a pair of high heels. Its pages flutter and fly around the streets of Manhattan as they scatter to find their way into new contexts and environments. A pile stands in front of the New York Public Library, read by a bus driver, blowing across the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, next to a stack of The New York Times. Photographs by Diane Arbus, Hujar, and Peter Beard are seen torn up among the trash of the streets, along with the face of Richard Nixon and a silkscreen of a piece of meat.

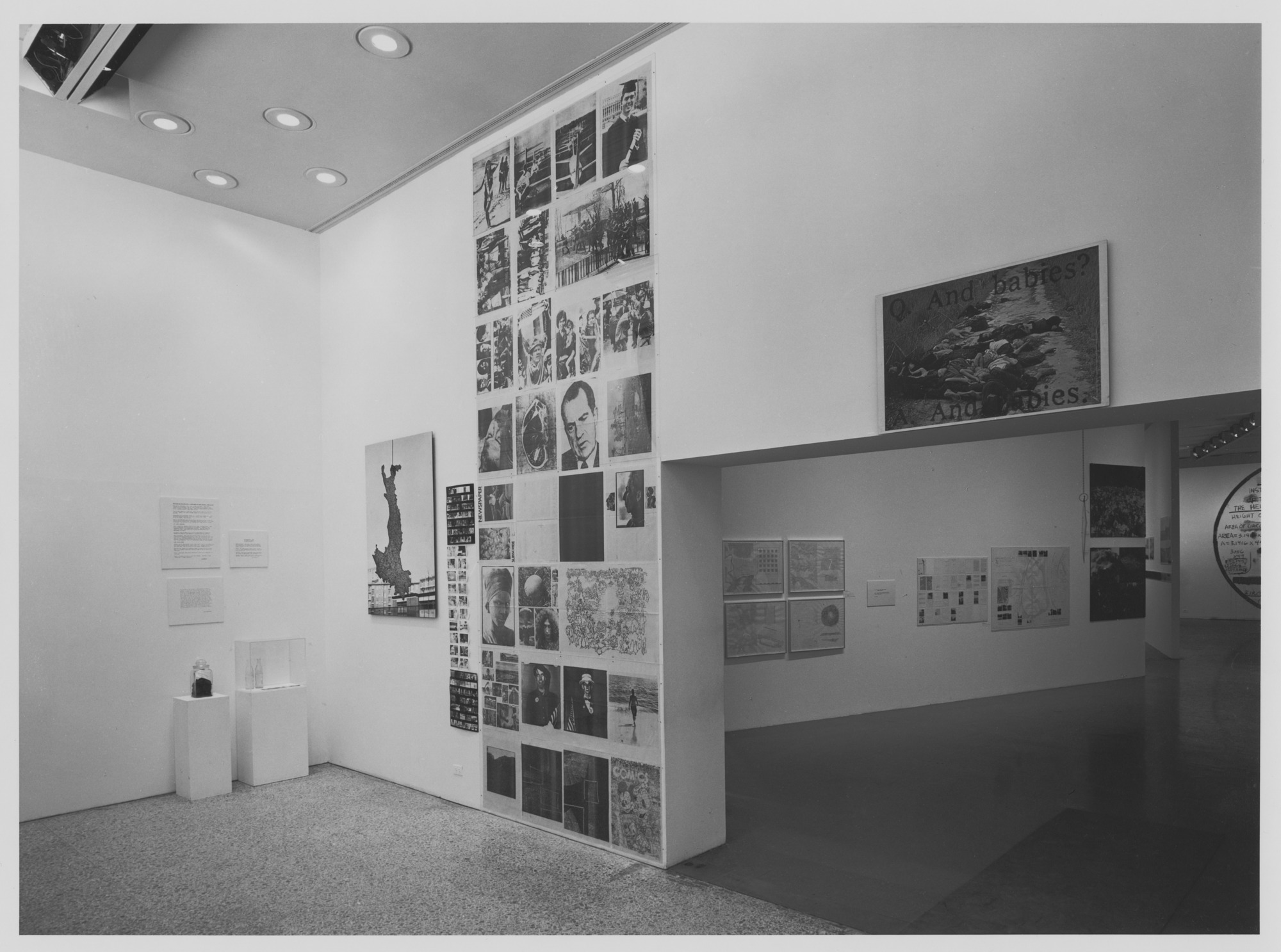

Images now famous are made ephemeral. The Polaroids were taken, presumably by Lawrence or Hujar, on the occasion of Newspaper being included in the landmark 1970 exhibition Information curated by Kynaston McShine. The exhibition was a large international survey on the development of early conceptual art and its engagement with shifting media technologies. The installation shots from the exhibit show the final issue of Newspaper in its 23×34” format, Vol II No 3 (Fig 9), deconstructed and stretching from floor to ceiling as a large grid of images. 6 The Polaroids are arranged next to the publication along with a contact sheet which is no longer present in the Information archive. The juxtaposition of Newspaper and the Polaroids within the white-cube environment of The Modern established a tension within the gallery space between what was signified as an art-object and simultaneously ephemeral trash on the streets. Most importantly though, something was expressed as to how the printed object and its images move, are consumed and handled physically by humans. The Polaroids show the publication’s images existing in public space and therein becoming part of an urban environment.

Courtesy MoMA Archives. Information exhibition, 1970. Papers. 6.172 – ‘Newspaper, Other Arts, Stephen Lawrence, Series’. Folder: IV. 62

The “museum number”, vol. II, No. 3, is in many ways radically different from other issues of Newspaper 7. The publication’s eclecticism, chaos, and juxtaposition of artworks and media is forsaken to fulfill the exhibition’s prompt for artworks that engage within a larger international dialogue on the nature of communication systems in an expanding ‘global village.’8 The museum issue features four more Environment spreads than previous issues, and what had been the publication’s recurring cast of artists is largely replaced by press images and more politically aware artworks that appropriate news images: the national guard storming Kent State, Nixon, Martin Luther King, a college student with a diploma, the Why Babies? poster of the Mai Lai massacre, and the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The majority of the photographs are the products of mass dissemination, the images every person in America was seeing through Life, ABC, CBS, and local newspapers. They form, quite literally, the environment, the unified visual language which mediates how society perceives reality. The issue totals five spreads by artists, and of the previous artists, Lawrence recycles a spread by Arbus from Ark (Fig 10), two ethnographic images by Peter Beard, and an image by Hujar taken on a roadtrip through West Virginia with Ann Wilson and Jim Fouratt. In removing almost all ‘artworks,’ the museum issue seems to depend entirely on the found image sensibility of Lawrence’s ‘Environment’ spreads.

fig. 9 – Information,exhibition view, 07/02 – 09/20/1970. Archive photo. The Museum of Modern Art, Archives, New York. Photography by James Mathews.

The effort at totalizing the publication into an ‘Environment’ spread opens up with nuanced clarity the micro to macro correspondences of the publication’s layout. When the issue is taken apart and hung on the wall, the layout design of the Environment, which forces a viewer to look at all images at once, is echoed in the publication’s larger construction. There seems to be an intent for the issue to be taken apart, to be viewed as a towering grid that evokes the consumption of the images as a collective whole. In the same way which Hujar arranged his photographs into a grid in 1986 at the Gracie Mansion Gallery, the installation at Information works to establish similar reading practices: A viewer moves in and out. One can begin by focusing on an image individually, but because of the proximity of other images, the viewer is forced to see any one among many. Fluid pairings are established between images in groups of two, three, four, etc, or as a total grid. When the issue is taken apart and presented in the way it was at MoMA, it is clear why the publication chose the type of format it did. In choosing the unbound broadsheet, the Newspaper was able to act as a type of package for transporting and establishing an exhibition. In one of the ways that it was intended to be seen, deconstructed, it physically occupied significant space. The publication became a type of timed performance. When it was over, the pages would be thrown away. Forty years later, those that remained would be disintegrating. MoMA keeps two issues of Newspaper. They are tightly folded in a box with some other papers. They are catalogued as a document of Information rather than as an art object.

Newspaper ceased publication in 1971 with one last issue in a different format than the rest. In an interview with the Village Voice, Steve Lawrence does not count it as part of the formal run of Newspaper.9 The issue was published to accompany the arrival of the the San Francisco genderfuck theater troupe The Cockettes and their opening act, Sylvester. The publication had been a contract to Lawrence and Hujar from Cockettes publicist, Danny Fields, in preparation for a set of performances in New York at the Anderson Theatre during the month of November 1971. The publication was quickly assembled to be given away at the performance’s intermission.

However, at some point after the Cockettes issue, Lawrence had a fight with Hujar, and they built a wall dividing their shared apartment.10 They grew apart. Later, in 1973, Hujar moved across the street to a loft on 189 Second Avenue, that had been previously occupied by Jackie Curtis. He built a darkroom and set up a studio. He later left this apartment to David Wojnarowicz. At some point in 1979 or 1980, Steve Lawrence got fed up with New York and returned to his home state of Texas. Some people have said he was working for a record company in Dallas; others mentioned the corporate headquarters of Neiman Marcus; his obituary states Steve Lawrence Advertising, Inc.11 One late night cruising along Christopher Street, Hujar ran into photographer Stanley Stellar, who inquired “Did you hear Stevie Groovy died?”12 According to a tombstone found on findagrave.com, a user-run database of tombstone photographs, Steve Lawrence died on October 22, 1983 in Clay County, Texas. The number of known deaths from AIDS-related illness in the US in 1983 was 2304.13

Peter Hujar died on November 26, 1987 from HIV/AIDS complications. The exhibition at the Gracie Mansion Gallery in 1986 was the final show within his lifetime. It can be argued to have been the culmination of his career, gathering photographs that spanned his entire oeuvre into one large production. While Hujar’s work with Newspaper may seem minor in the larger scheme of his career, his involvement with the publication came at a crucial point when he was deciding between devoting his efforts towards commercial photography or a more personal art photography. As the 1970s were welcomed, the arts scene in the East Village was changing. A post-psychedelic form of theater, music, and film was emerging in and around Hujar’s neighborhood. Something clicked within Hujar and in 1972 he decided to abandon the world of commercial photography, and make his living strictly on his photographs and small contracted jobs from friends like the ones that appeared in Newspaper. He took a vow to live what was then the life of an artist. For the rest of his career, many friends would often remark that Peter was the poorest person they knew.

Marcelo Gabriel Yáńez

Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez (b. San Juan, Porto Rico, USA, 1996) is a photographer and researcher living in Palo Alto, CA. He is currently a first year Ph.D. student studying American art in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University. His honors thesis was titled “On Peter Hujar, Steve Lawrence, and Newspaper (1969-1971)”. Between 2016 and 2017, he published a revival of Newspaper which can be found at The Picture Newspaper. In July 2018 he co-curated The Unflinching Eye: The Symbols of David Wojnarowicz at the Mamdouha Bobst Gallery of the NYU Library.

References