“My art began by disappearing.

I made an offering for the sea to erase.

The waves weave our breath, in, out.

Dissolving gives life to what comes next.”

Cecilia Vicuna1

Cecilia Vicuña (born 1948, Santiago, Chile). Skyscraper

Quipu (Incan quipu performance, New York), 2006. Rephotographed 2018. Cotton. Collection of the artist. © Cecilia Vicuña. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong. (Photo: Matthew Herrmann)

This beautiful excerpt from Cecilia Vicuna’s Artist Statement was displayed on the wall next to Disappeared Quipu, her sculptural and luminous “poem in space” on view at the Brooklyn Museum in the summer of 2018. Describing, in both literal and metaphoric ways, the banished symbols of the ancient Incas, her installation paid homage to alternate modes of communication – handicrafts and textiles, sounds and images – which shaped the records and the narratives of this complex civilization not tied to written language. The knotted “quipu” strings central to the installation, which were banned in 1583, “began by disappearing,” as she said, and their absence “gave life” to her understanding of the South American cultural heritage into which she was born.

Inca artist. Narrative Quipu, 1400–1532. South Coast, Peru. Cotton, camelid fiber, 13 x 37 in. Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Dr. John H. Finney, 36.718. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

Chilean by birth, Vicuna left her country to study, and then to escape Pinochet’s dictatorship; she has lived in London, Bogota and, since 1980, New York. Like the Cuban Ana Mendieta and the Argentinian Liliana Porter, she is a Latin American woman whose experience of the world has been shaped by travel, by relocation, by exile (both of necessity and choice.) All three of these artists have lived multiple perspectives and realities. They have chosen to explore the interstices between fixed spaces, homelands and national identities. In Disappeared Quipu, Vicuna is peering across time and space to understand the Incas. She is rediscovering the language of the ancient textiles of the Andes in the collections of the 21st century Brooklyn Museum, bringing history forward and superimposing the geographies of the two Americas. It is the premise of this essay that this working method, this perceptual pattern and indeed this interstitial vision of the world is becoming increasingly common in contemporary art. But it is especially pertinent to, and descriptive of, the art of Latina pioneers like Vicuna, Mendieta and Porter.

“Now I realize you can live (in New York) a thousand years, but you will always be a foreigner. Not long ago, someone asked me when I finally became integrated here, and I replied that the interesting thing about living here is that you don’t have to integrate. People have the right to continue being different, to live in their own unique, personal countries; here you can invent your own country….” Liliana Porter2

Liliana and Ana were friends: good friends, the kind who share dinners and acquaintances and personal stories and send post cards when they travel. Part of an active group of Latin American artists that included Louis Camnitzer (Liliana’s first husband), Luis Felipe Noé and José Guillermo Castillo, Porter originally arrived in New York as a tourist on her way to visit the museums of Europe. Attracted to the city, she decided to stay. But there was a caveat. “The one thing I always knew that I wanted,” she told Inés Katzenstein, “was to maintain my relationship with Buenos Aires – to not lose my identity as an Argentine, even if that definition is totally abstract, subjective and very difficult to explain.”3 Though resident in New York State for over 50 years, her decision to be different – to remain deliberately foreign, to create her own “unique, personal country” in her mind, her life and her art – has been determinant.

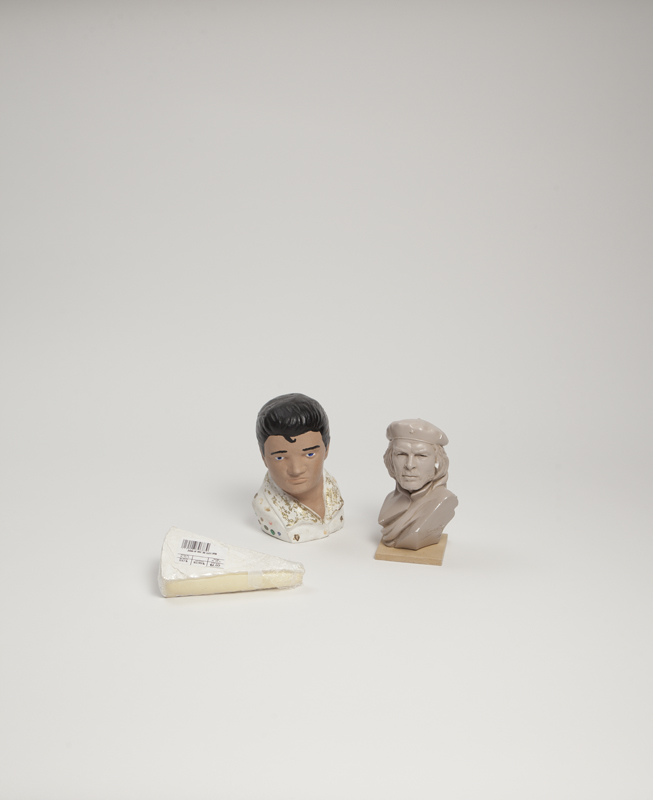

On some level, this deliberate disjunction is the centerpiece of her artistic practice. The idea of “inventing” her own country is paralleled by her understanding of her works, which she sees first and foremost as philosophical propositions, and later as material, formal statements. When teaching, as she told me in an interview in August4, the first thing she drives home to her students is that an art work is not a reflection of, or even tied to, any reality – and that is its strength. It is an arena where a new reality can take shape, where a rabbit can levitate or Che Guevera can hang out with (a piece of a cheese named) Joan of Arc, and from her perspective that new vision must take precedence over technique or medium. As she sees it, a piece of paper or canvas is not a mirror. It is a separate world with different rules, where anything is possible. Like an invented country.

There’s a lot of unfilled space in Porter’s works. Whether drawings, paintings, prints, photographs, installation or mixed media works, they are notable for their emptiness. Inés Katzenstein postulates that this surface blankness is fundamental to Porter’s expression, because it allows her to concentrate on “relational events.”5 Subject matter – whether a drawn sickle or a photographed plastic Jesus, a figurine of a man or a bear or a painted house – is unmoored from its context, taken out of its natural habitat. Once repositioned in Porter’s artistic arena, these images or objects (no matter how divergent in origin, culturally or geographically) seem to share the same space-time, to encounter each other as “virtual travelers…who coexist in a new continuum, a hyperspace where various times and spaces interact.”6 The empty space – whether defined by a canvas or photographic picture plane, a wall or a wooden cabinet — gives the illusion of expanding into depth, allowing the focus on disparate and sometimes miniscule images or objects (often small mass produced bric-a-brac from flea markets or shops), to become so intense that the difference between representation and reality seems to collapse. Katzenstein remarked that Porter’s photographs create a “theatre of replicas,”7 where these deracinated, pop cultural tchotchkes, alone and unprotected, seem to reach out across space, time, culture and ideology to engage – with each other and with us the viewers.

Installation view in the exhibition “Liliana Porter: Other Situations”,

El Museo del Barrio, New York, until January 27th, 2019. Photograph Courtesy Martin Seck

This temporal and spatial displacement is key to Porter’s vision. Her images may be charged and are often political in precisely their banality. In the context of her works, pop culture pictures of Jesus and Che lend their ideological weight to capitalist icons like Elvis and Minnie Mouse, effacing cultural, philosophical, economic and social differences as they “pose” together or seem to embrace. Mickey Mouse engages the White Rabbit. A toy soldier shoots at an outsize piggy bank. A tiny man standing on a full sized white chest seems (implausibly) to hack up its wooden surface with a pickaxe, while a miniscule woman begins to sweep endless amounts of red dust with her impossibly small broom. This Forced Labor series gives a hint as to the seriousness of Porter’s thinking and the implicitly political nature of her art, however entertaining and surprising it may be. The scales of things are out of whack, but so are their geographies, cultures, religions, ideologies and identities and interactions. Porter sees this in not only artistic but political terms, since in her mind her works visualize and propose the possibility of “the encounter with the Other.”8 Her cheap, disposable, mass produced “characters” – as Gerardo Mosquera calls them9 – “cross through impossible borders, like an Alice in Wonderland.”10 Small wonder that Liliana most often cites Lewis Carroll and Jorge Luis Borges as her major influences. Moving from popular culture to the world of art, creating an environment within which dialog uncannily takes place in spite of radical difference, Porter’s subjects inhabit her “invented country.”

On the night of her opening at El Museo del Barrio in New York in September, my first stop was the Delacroix exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. That show ended with a grand finale, the remnants of the damaged Lion Hunt (1855), which was extraordinary in its grand scale, its passion, its rampant destruction and its densely woven colorful surface. Moving uptown to Liliana’s show, I looked at To Sweep, a large white canvas whose only imagery is in its mid-section – where a brush, similar to one used to clean bathtubs, has swept across a plethora of tiny plastic objects like the gale winds of a hurricane, crushing horses, carriages and other more mundane tchotchkes in a barrage of paint. Empty where Delacroix’s painting was packed full, its “contents” miniscule, plastic, hard to discern and sometimes domestic instead of monumental and dramatic, Porter’s work blew my mind. It was the exact corollary to Delacroix’s painting, a visualization of destruction, a narrative told from another (more feminine, and ironic) point of view, in ways that implicated not the beasts but the most banal among us.

Ana Mendieta

Cuba New York Rome

She found her roots here11.

Home – and its elusiveness – is an important subject in the art of both Liliana Porter and Ana Mendieta. For Porter, it is an anchor, and unreachable. Her tiny painted figures sometimes try to traverse vast landscapes to arrive at aspirational, impossible domestic destinations. Like the thought of Buenos Aires, home is always there for Porter, hovering in ways that seem increasingly abstract. She created a large painting of a small cottage against an almost white background in 2007, and then re-used it in various formats (installations, photographs), allowing the structure to function within a hall of mirrors not unlike Duane Michals’ photographic sequence “Things are Queer” from 1973. Entitled “The Resemblance,” the painted house seems to float in the pictorial landscape within which it is embedded. Its scale creates a sense of intimacy and proximity, but at the same time its environment gives the illusion of expanding, making the cottage feel recessive, distant, almost out of reach. The small building, and the spatial dissonance that surrounds it, was on my mind the day I visited Porter’s studio in Rhinebeck, New York. As I was looking out the window of her home, I spotted that identical structure: small, white and yes, simultaneously near and far, its distance really, literally, inexplicably hard to gauge. I gasped; Porter laughed. I wondered whether art had imitated life, or instead just played tricks with my eyes and my mind.

Liliana likes to collect and save things, not only the bric-a-brac that populates her works but also her correspondence. Included in her archive are several postcards from Ana – postcards presumably composed in Rome while Mendieta was living and working there, but sent through the United States Postal service. (Older Americans will remember that in the 1970s and 1980s travelers often bought and wrote postcards abroad but sent them home with friends to be mailed, thereby avoiding large postal fees and delays.) Only one of the three touristy commercial cards Porter showed me has a direct relationship to Italy. There’s a postcard of a tropical parrot jungle scene, one of the Amstel Hotel in Amsterdam, and one depicting the sculpture “Love and Psyche” that resides in the Capitoline Museum in Rome. All three describe her voyages, her work, insights about her relationships, feelings and daily life. An American citizen by this time, Ana used the mail to assert her dislike of New York’s increasing commercialism from her studio in Rome, by writing to her Argentinian friend living in Manhattan. Mendieta chose a mobile life, of shifting spaces and elusive boundaries, and she inhabited, loosely, the cracks between the near and the far. Like Porter’s voyagers, always both close by and out of reach, Ana’s travels were a means of putting down roots in the interstices between places – of displacing the emotional targets, and traversing impossible borders12. They were, as Jane Blocker has observed, a way to “make exile her home.”13

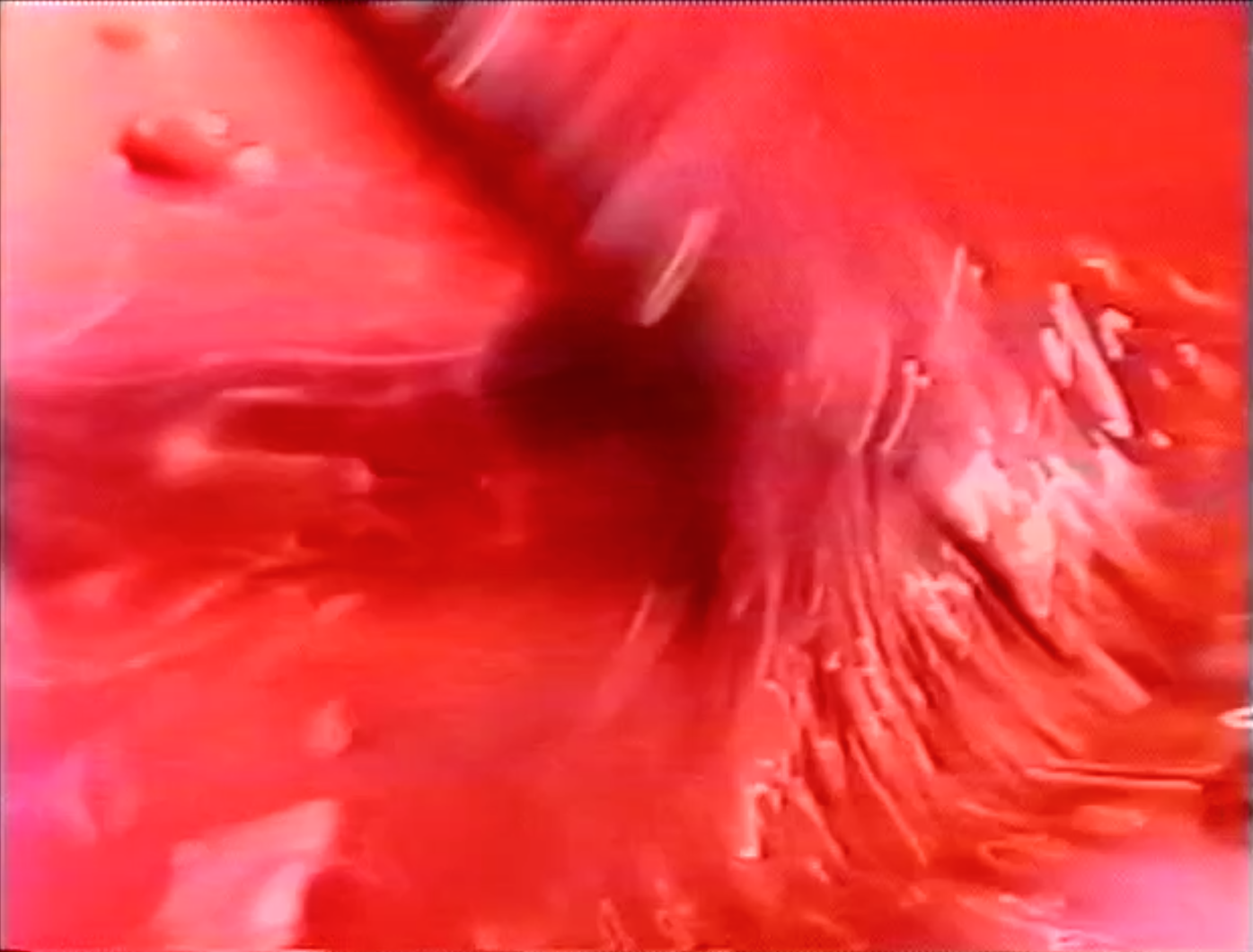

Ana Mendieta, Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (Firework Piece), 1976, film super-8 © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

Whereas Porter uses her art to create an arena for encounters, Mendieta’s visualized absence. This is true from the earliest works, performances documented by photographs and films, where clues are strewn around her room or in the street, pointing to some violence that must have occurred – out of the frame, in the past. Ana chose to use photography to manifest what Roland Barthes called, in Camera Lucida, the noeme14 of the medium: the fact that what you perceive as you look at any given picture was once present and is no longer. A photo, seen from this point of view, can only attest to absence; it is the evidence that what is in front of your eyes “has been.” For Barthes at the end of his life, the medium was first and foremost about Time and its mysterious, uncanny displacements. For Ana Mendieta, the exile who was sent away from her country and her family in Cuba for political reasons when she was 12, whose teen years were spent in foster care in the United States deprived of everything (including her native tongue) that was familiar, temporal disruptions were a potent subject.

Critics like the brilliant Jane Blocker see Ana’s Silhuetas – the earth drawings or sculptural carvings that Mendieta loosely traced from her body in Iowa, in Mexico, in Cuba and elsewhere, known to us primarily through photographs – in this vein. They are spectral doubles of the artist, shadows that allude to her presence while signifying her absence. “In these shadows,” Blocker writes, “she is always already somewhere else. They cannot tell us who she was, only where she has been. They force us to ask, “Where is Ana Mendieta?”15 Those who have written about the artist often trace the origin of her work to the trauma she experienced in her exile, as if her life began in the shock of a new culture at the of age twelve. But perhaps that shock also functioned in another way, more constructive, as an opening toward an expanded perspective. Perhaps it provided her the opportunity to choose not to integrate, to “invent her own country,” to imagine a conceptual territory born out of multiplicity and enhanced by accretion rather than rupture. Porter feels strongly about this, seeing parallels between her attitudes and Mendieta’s. “While she was growing up in the US,” Porter told Sean O’Hagen in an interview, “Ana voluntarily kept her identity and her culture while simultaneously integrating to the new codes. She spoke perfect English. Her art reflects all of these issues and circumstances.”16 For Porter, Ana’s life was not an either/or; it was synthetic, aggregated, layered like a collage. As Liliana assured me, Mendieta knew how to use her Latin American heritage to her advantage in the international art world she traversed.

Ana Mendieta, Guacar (Esculturas Rupestres), 1981/2018, photograph © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

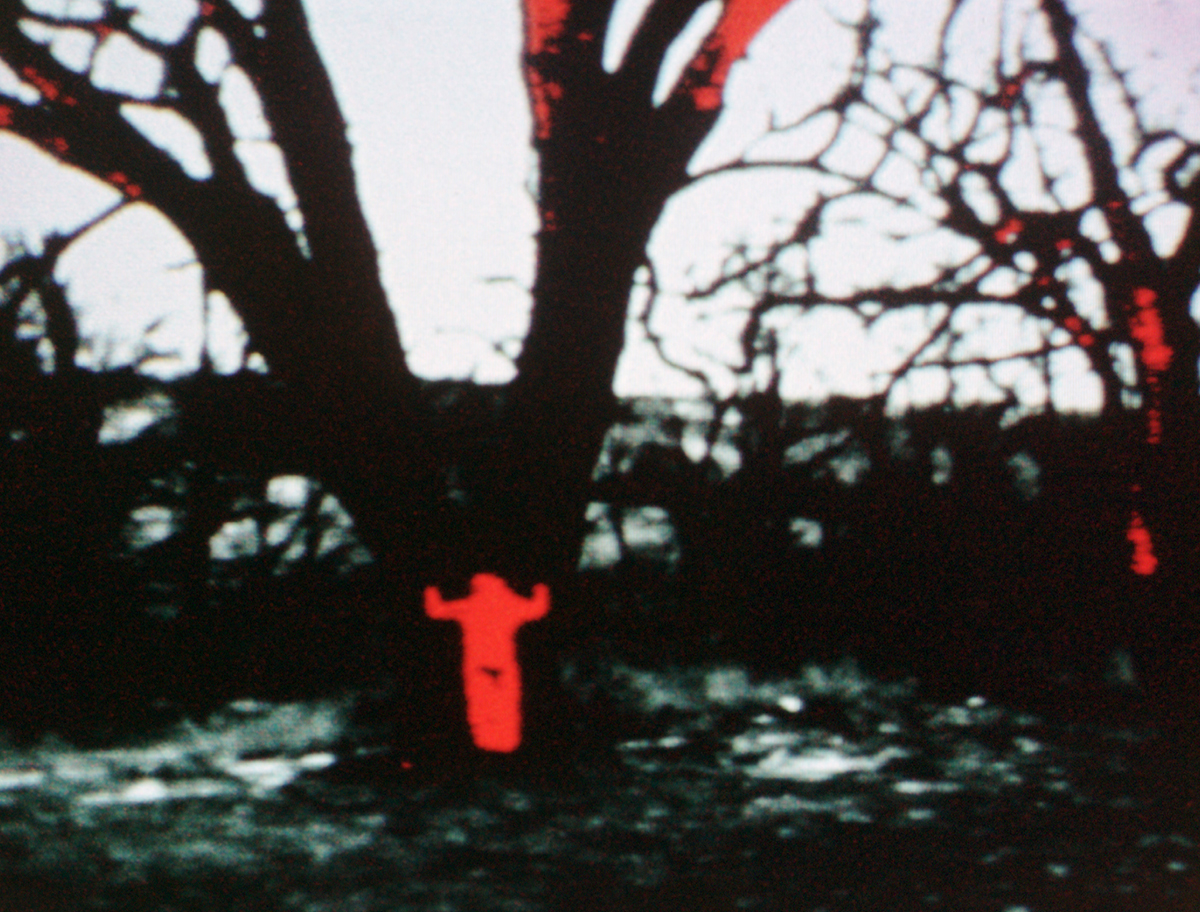

Viewed in this light, the traces (performances, drawings, sculptures, photographs and films) designating where Ana “has been” – spatially, temporally, geographically, culturally – together create a network linking her body to myriad cultures, to history, the future, the earth. In this outreach, her works can be seen as the precursors of Cecilia Vicuna’s Disappeared Quipu. They were not an attempt to find a lost past, become a feminist goddess, or merge with a nature devoid of culture. Never nostalgic, her art “skipped across time and through time, giving a physical shape to time. By inscribing her shape into the archaeological landscape, it was as if the artist had subtly merged with that place and its past. She was operating as an artist in the present tense with contemporary gestures and artistic methods, yet she was magically connected to the past, the ancient culture. The image was physical. It was temporal. It was of the earth. It was in the mind.”17 It was multifaceted and multilingual; its meanings were as elusive and as transient as the Silhuetas washed away by the sea or obliterated in fire and smoke. Like Vicuna’s Quipu strings, Ana’s traces “began by disappearing.” They “gave birth” to her body’s mobility, its rootedness in an expanded and virtual time and space. Seen from this perspective, Mendieta’s painful experience of exile was what allowed her, like Liliana and Cecilia, to become unstuck without being unmoored, to live permanently in the cracks between places and languages, cultures and historical moments. Her art was her postcard, sent to describe this shifting space, with its elusive borders, to those of us who stayed at home.

Ana Mendieta, Imágen de Yágul, 1973/2018, photograph © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Gallery Lelong & Co.

“The constant displacements, the continual disappearing acts that that left their evidence of having been, all those open wounds silhouetted over and over again. Things burn themselves out. The films force us to endure that process, exiled from completion.” Rachel Weiss18

When I knew Ana, in the 1970s, she was not usually identified as a filmmaker, though many of us knew that she made films. Not being particularly close to her, knowing her through Mary Beth Edelson, Carolee Schneeman and others in the active art world feminist movement, I most often encountered her depictions of solitary performances. Through the medium of photography, I saw the records – of blood on the walls and sidewalks, of carvings, drawings and sculptures etched on land, in sand and surf and on the walls of caves. I saw her flesh covered in grass, feathers, blood, mud and rocks. I saw, in other words, the myriad traces left by her passage through locations in different countries, on different continents, at different times. Transient séances, immobilized and preserved through the stop-time of photographs, became as mobile, portable and spectral as the artist herself.

What this means, of course, is that Ana has, recently, posthumously, crossed another border: she has augmented her repertoire, adding filmmaker to her usual titles of photographer, performance artist and sculptor. This is important, for it forces us to re-think and re-view her work within an expanded framework, one that incorporates movement and time more evidently, more forcefully. Being recognized as a filmmaker, within the context of performance and installation, was very difficult during the years Ana was alive. There was little framework for critical assessment and exhibition of moving images or installations until the year before her death, when the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam mounted The Luminous Image exhibition of video works. The traveling exhibition Covered in Time and History, therefore, is significant in this re-positioning of Mendieta’s achievements, not only in its assumption that these works are important but also in the effort that was put into the films’ conservation and restoration. The exhibition, in fact, demands that we re-evaluate her entire œuvre – after her death, when she doesn’t have a voice.

Ana Mendieta,

Untitled: Silueta Series, 1978, film super-8 © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

I am treading lightly here, since I don’t really know how exactly Ana saw these unedited films within her body of work, whether (as some suggest) they were simply sketches for her or whether she aspired to have them recognized as independent statements. Suffice it to say that she did enough of them to have their placement within her body of work make a difference in how we perceive her as an artist, and she made them continually, throughout her career. She began with her difficult early works, about rape, blood, murder, violence, voyeurism and apathy. Passing into her landscape works, she moved away from menace and towards connection. As Rachel Weiss writes in the catalogue, “The site of intensity relocates to the landscape, which develops a fluid interface with the body. The membrane of the self, so harsh at first, becomes transactional.”19 The films show that transaction as a process, as Ana and her surrogate Silhuetas are buried under, flow with or are dissolved into the natural world – presumably allowing her, and us, to experience unions more primal than those of citizenship.

The continuity of these transactions is film’s forte, but their temporal flow leads us down unexpected pathways. Unlike the photo works, which freeze a moment, creating a fixed symbol that summarizes the performative experience, the films exist in what we perceive as “real” time. There is, therefore, the anticipation of a narrative arc and resolution; unlike photographs which preserve the past, films move toward a future. But this promised resolution never materializes, it is withheld in these works, devoid of editing and manipulation. The critic and curator Rachel Weiss has called attention to the claustrophobic nature of much of Mendieta’s camera work. She writes that Ana’s “Cyclopean vantage point”20 establishes a closure within the open landscape, creating a spatial disjunction uncomfortable for both us and the artist. The writer sees this disjointed space as disruptive, especially in those films where viewers simultaneously perceive both Mendieta’s merger with nature and her physical discomfort or obliteration within it. For Weiss, the human-nature truce articulated in the films is “provisional,” and the artist’s resulting isolation, her “exile,” is akin to “being in a social body that she can never be within… The hope of union, expressed as a dynamic between self-nature, gradually becomes a diary of the accumulating fact of non-union.”21 As she sees it, the films make clear that Ana’s physical body and its surrogates – buried, flooded, scratched, washed away or burned in effigy – cannot achieve the merger to which the artist seemingly aspires, a merger perhaps implied symbolically in the photographic and sculptural works. “These films hurt,” Weiss writes, and not only physically. They hurt because in the end they are about “the abandonment of the ministrations of myth…. They kick us out of the garden.”22 Short, inconclusive, they end when Ana disappears, or walks away.

Ana Mendieta, Burial Pyramid, 1974, film super-8 © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

I wonder how Mendieta would feel about this interpretation. Her works appeared during the early heyday of feminist art, and they were originally celebrated within the context of the Goddess movement (with which she had serious disagreements). Her silhouettes on rocks, soil and sand were perceived as “Herstories”, inspirations for women trying to express the ancient source of their power and heal the wounds of separation afflicting both nature and culture. But now we are in a different time, and the placement of the restored films as front and center in her œuvre adds a new wrinkle to this tale – a wrinkle that resonates, perhaps, with Liliana’s delight in non-integration. Rather than confirming Mendieta’s merger with universal rhythms, the films instead make manifest her separation, and her solitude.

When Ana died in 1985, after falling (being pushed?) from the window of her husband Carl Andre’s 34th floor apartment in the East Village, she landed on the roof of our local deli, right across from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts where I was then and am now a Professor. In the middle of Manhattan, far from nature, her body (according to people familiar with evidence presented during Andre’s trial; he was acquitted) eerily resembled certain of her photographs. Bloody, broken, covered with a sheet, it left its traces on the rooftop’s surface. Life, we fearfully understood, had in the end imitated art. But this time, our gifted and spirited friend could no longer get up and walk away.

Shelley Rice

“Ana Mendieta. Covered in Time and History”/Jeu de Paume

“Liliana Porter: Other Situations”/Museo del Barrio

“Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu”/Brooklyn Museum

Ana Mendieta/Books

References