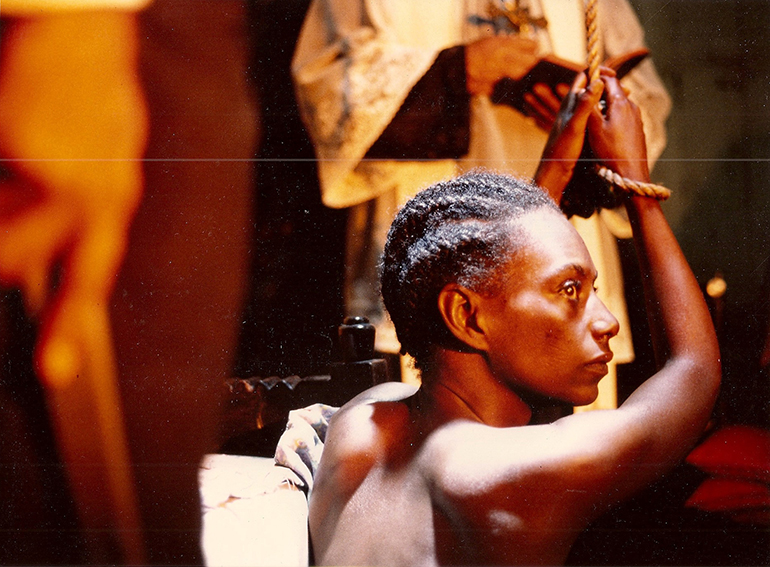

Marie-Pierre Duhamel and Hailé Gerima have proposed a rebellious playlist with music that Gerima and his companions of the L.A REBELLION film movement have brought into their cinema.

Marie-Pierre Duhamel: Is it true to say you have a musical approach of your films? Can we talk about the influence of music, like sung music or sung poems as your father used to do and as you also did in Ethiopia, before you went to the United States? When you were in the USA, did the influence of blues and jazz and your connection with African-American music play a part in finding your own “accent” and your own narrative system?

Hailé Gerima: Certainly… Firstly, my own struggle with jazz began like this: I come from Ethiopia and fundamentally I come from blues. I didn’t have immediate affinity to jazz – It’s really through friends like Larry Clark I began to like it. The first few records I bought in Chicago were very meaningful, it was blues: Lightnin’ Hopkins, Gospel… It talked to me because the idea of blues travelled across the ocean from Africa. When you look at some African blues, it’s very jazzy. When you look at it carefully, the collective participation on some African blues brings it into what I think is the early jazz. But then, when it gets to America, this blues started to incorporate the experience of enslavement and oppression and black people began to transform, in Haiti, wherever they were, they transform a jazz idea. This is how I began to be very close to jazz. To a point I have the biggest jazz collection of all kinds because it really tapped into me.

Now, about the relationship between jazz and cinema, when I did Child of Resistance, I wanted this jazz group Larry Clark introduced to me, but I used them without wisdom, wall to wall in the film. It was the biggest mistake, but I learned a lot. You have to understand the narrative power of jazz. It is not good as an accompaniment of a story, you’d rather use it as a narrative element itself. I think I started to go for this narrative power of jazz into storytelling in Ashes and Embers (1982), or even in Harvest (1976) or in Bush Mama (1976). And, of course, in my following films, until this new film I want to do now, called Chicken Bone express, that I present as a “jazz narrative cinema”.

The power of jazz is that it doesn’t have rules and regulations. Jazz is the most democratic music: it allows the brain to go where it wants to go intuitively. All the jazz musicians work hard to master their instrument, in order to gain freedom… Freedom is the narrative logic of the jazz. This amazing power is like dreaming. The closest to a film is a dream. Dream has no logic. It can go, based on its immediate improvisational feeling or reality. This is how I write a script. I have learned to leave myself alone, sit down to write and all will come in. Like the other day, I just sat down, I didn’t plan it, I didn’t organize it, it all came in. The story just weaved into itself because I have learned how my brain, independent of my conscious effort, also transforms my narratives once I’m pregnant of them.

Like the freedom of the jazz, the brain’s freedom is not bounded by rules and regulations. For the script of Ashes and Embers, I began to consider the characters as instruments. The grandmother was the “French horn”. I told the musicians that I wanted the grandmother to be this instrument and the grandson to be this instrument. It was very imperfect… But now, in this film I want to do, things are getting a better location. Jazz is getting a better place to become the narrator of the story, rather than just accompanying it.

What the official history doesn’t tell is that Jazz came to Africa to support rebellion and resistance. The initial Jazz was underground. Before it came in Congo Square in New Orleans, before it came above ground, jazz was underground, it was a rallying point to rebel. If you think about it, it is really the African insistence to resist to the deletion of the origins. It’s like fighting to sustain Africa, but fighting to sustain each other’s village, the village where we came from. So now, coming to America, colonized, for me it was a personal transformation, taping into what was there before. But still, I remain an immigrant. I cannot deny my 21 years upbringing in Ethiopia. I cannot deny that my father was a playwright. He never knew Shakespeare, Molière, Ibsen, Chekov. But he wrote amazing plays, filled with our Nilotic civilization. I’m beginning to be aware the fact that I played in his plays… When you see The Children of Adwa, that’s my father singing, he wrote musical plays. I didn’t know how important it was until I went to Chicago to the drama school and I realized that my father did this all the time. One day, in class, during the sixties, we were doing mobile theater in Latin America as a big thing, street theater in Chicago… But my father was doing street theater before! When I was growing up, I was working for him.

So, you are pushed to rediscover a certain wealth that you have under your nose and that you were negating. Colonialism always makes you want to decapitate yourself from your original everything: the food, the culture, the thought system that has been brought into you. So, in the end I will say, I went back to this thought system: I was not lost. Finally, my thought system needed to be defended. The life I lived in America was always by defending my thought system. And then I met African American who were trying to defend their own experience. And that unity is where it came.

Hailé Gerima, 2017

Interview: Marie-Pierre Duhamel

Transcription: Aurélien Ivars

A selective L.A. Rebellion filmography :

Melvonna Ballenger, Rain, 1978 / U.S.A. / 16 min

Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep, 1977 / U.S.A. / 81 min

Larry Clark, As Above So Below, 1973 / U.S.A. / 52 min

Larry Clark, Passing Through, 1977 / U.S.A. / 105 min

Julie Dash, Four Women, 1975 / U.S.A. / 7 min

Jamaal Fanaka, A Day in the Life of Willie Faust, 1972 / U.S.A. / 16 min

Hailé Gerima, Hour Glass, 1971 / U.S.A. / 13 min

Bernard Nicolas, Daydream Therapy, 1977 / U.S.A. / 8 min

Alile Sharon Larkin, Hidden Memories, 1975 / U.S.A. / 7 min

Billy Woodberry, Bless Their Little Hearts, 1984 / U.S.A. / 80 min

Marie-Pierre Duhamel: serait-il juste d’affirmer que vous avez une approche musicale de vos films ? Peut-on parler de l’influence de la musique, de la chanson ou de la poésie comme votre père ou vous-même faisiez en Éthiopie, avant d’arriver aux États-Unis ?

Quand vous étiez aux États-Unis, est-ce que l’influence du blues et du jazz et votre connexion avec la musique afro-américaine ont joué un rôle dans votre démarche pour trouver votre propre voix et votre propre système narratif ?

Hailé Gerima : Bien sûr, parlons-en. Tout d’abord, je n’ai pas eu un rapport facile avec le jazz. Je viens d’Éthiopie, et fondamentalement, je viens du blues. Je n’ai pas tout de suite aimé le Jazz. Ce n’est que grâce à des amis comme Larry Clark que j’ai commencé à l’apprécier. Les premiers disques que j’ai achetés quand je suis arrivé à Chicago sont d’ailleurs très révélateurs, c’était du blues : Lightnin’ Hopkins, du gospel… Cette musique me parlait, car elle vient d’Afrique, elle a traversé l’Atlantique pour atteindre les États-Unis. Et le blues africain, c’est très jazzy. Si on en écoute attentivement, la participation collective qu’il y a dans certains blues africains représente pour moi le début du jazz. Mais une fois arrivé en Amérique du Nord, ce blues a été nourri par l’esclavage et l’oppression des Noirs. À Haïti, où n’importe où ailleurs, ça s’est transformé en une musique plus jazz. C’est ainsi que je me suis beaucoup rapproché du jazz. J’en suis même arrivé à avoir une immense collection de tout type de jazz, car ça m’a vraiment parlé.

Pour en venir à la relation entre le jazz et mes films, quand j’ai réalisé Child of Resistance, j’ai fait appel à un groupe que Larry Clark m’avait fait écouter, mais j’ai utilisé leur musique sans réfléchir, d’un bout à l’autre du film. C’était une très grosse erreur, mais j’en ai tiré des leçons et j’ai beaucoup appris. Il faut bien se rendre compte du pouvoir narratif que possède le jazz. S’en servir comme accompagnement musical d’une histoire, ce n’est pas terrible, il faut plutôt le concevoir comme un élément narratif en lui-même. C’est ce que j’ai commencé à faire dans Ashes and Embers (1982), ou même dès Harvest (1976) ou Bush Mama (1976). Ainsi que dans tous mes films suivants, jusqu’à mon projet actuel qui s’intitule Chicken Bone Express, que je présente comme étant du « cinéma doté d’une narration jazz ».

La puissance du jazz, c’est qu’il n’y a aucune loi, aucune règle. C’est la musique la plus démocratique qui soit. Elle libère l’esprit, il peut aller là où ça lui plait, de manière intuitive. Tous les musiciens de jazz travaillent dur pour maîtriser leur instrument afin de parvenir à cette liberté… La liberté, c’est la logique narrative du jazz. C’est un pouvoir extraordinaire, proche du rêve. Le rêve est ce qui se rapproche le plus du film, il ne suit aucune logique, il réagit selon des sentiments ou une réalité qui est improvisée. C’est comme ça que j’élabore mes scénarios. J’ai appris à m’isoler, à m’asseoir et à écrire, et tout vient naturellement. Comme l’autre jour, tout est venu tout seul sans rien planifier. L’histoire s’est tissée d’elle-même, car j’ai appris à laisser mon cerveau transformer mes récits en gestation, indépendamment de tout effort conscient.

Comme dans le jazz, la liberté de l’esprit n’est soumise à aucune règle. Pour le scénario de Cendres et braises, j’ai envisagé les personnages comme des instruments. La grand-mère, c’était le cor d’harmonie. J’ai expliqué aux musiciens que la grand-mère correspondait à tel instrument, le petit-fils à tel autre, etc. C’était loin d’être parfait… Mais pour mon film en préparation, les choses prennent une meilleure tournure. Le jazz y trouve mieux sa place, c’est lui le narrateur de l’histoire, ce n’est plus un simple accompagnement musical.

Ce que l’histoire officielle ne raconte pas, c’est que le jazz est venu en Afrique pour aider les rébellions et les résistances. À l’origine, le jazz est une musique underground. Avant qu’il apparaisse sur la Place Congo, à La Nouvelle-Orléans, avant qu’il sorte au grand jour, le jazz était une musique clandestine, un point de ralliement pour se rebeller. Si l’on y réfléchit bien, il incarne vraiment une volonté de résistance face à l’effacement de nos origines africaines. C’est une sorte de lutte de préservation pour l’Afrique, comme un combat pour aider le village d’origine de chacun d’entre nous. Donc le fait d’arriver aux États-Unis, pays colonisé, a provoqué en moi une véritable transformation, en réaction avec le passé. Et pourtant, je reste un immigré avant tout. Je ne peux pas renier mes 21 années de vie en Éthiopie. Tout comme je ne peux pas renier le fait que mon père était metteur en scène. Il n’a jamais connu Shakespeare, Molière, Ibsen ou Tchekhov, mais il a écrit des pièces formidables, imprégnées par notre civilisation née du Nil. Et je me suis rappelé que j’avais joué dans les pièces de mon père. Quand vous voyez les enfants dans The Children of Adwa, il s’agit des chansons de mon père, c’est lui qui a écrit la pièce. Je n’ai pas réalisé l’importance que ça avait pour moi avant de suivre les cours de l’école d’art dramatique à Chicago. C’est là que je me suis rendu compte que c’était exactement ce que mon père faisait. Un jour, c’était dans les années 60, nous avons étudié le théâtre ambulant en Amérique latine et le théâtre de rue à Chicago. Et mon père faisait justement du théâtre de rue ! Quand j’étais petit, je participais à ses créations.

C’est ainsi que j’ai redécouvert un certain savoir que j’avais en moi, mais dont je niais l’existence. Le colonialisme cherche toujours à vous déraciner, à vous couper de vos origines : la cuisine, la culture, le système de pensée avec lesquels vous avez grandi. J’ai donc fini par revenir à ce système de pensée. Je n’étais plus désorienté. Ma façon de penser devait être défendue, et c’est ce que j’ai toujours fait dans ma manière de vivre aux États-Unis. Et j’ai rencontré des Afro-américains qui tentaient de défendre leur propre vécu. Et c’est là qu’une certaine unité a pu être atteinte.

Hailé Gerima, 2017

Entretien : Marie-Pierre Duhamel

Retranscription et traduction : Aurélien Ivars