—

First she was found, as announced in the title of one of the two documentary films about her (Finding Vivian Maier), but now it can be justly said her life now requires posthumous invention. And, for the most part, this invention is necessitated by Maier’s voluminous production and its entrance into the photographic marketplace. This, however, is only one of a number of issues raised by both her life and work. As it happens, her job as a nanny – an explicitly gendered profession – was itself an occasion for much of her photography. It also risks becoming a branding moniker: Who Took Nanny’s Pictures? is the title of the BBC documentary, and citing the now-adult children she once minded, the news media have likened her to Mary Poppins. Looking at her many self-portraits reflected in mirrors and windows, there seems very little Poppins-like in her dour, impassive features. Nevertheless, despite the unknowability of this deeply secretive woman and the many lacunae in her biography, her new-found fame as a so-called street photographer, requires a story, a narrative, a way to link the life with its massive production.

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, undated

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In her provocative essay of 1984, “Landscape/View: Photography’s Discursive Spaces,” Rosalind Krauss addressed the complexities (and contradictions) of the art historical notion of “oeuvre” when applied to photographic production. As Krauss observed, those photographic histories constructed to conform to art historical models require equivalent concepts of authorship, intentionality and some claim for the works’ internal coherence or unity. Using as one of her examples the thousands of photographs made by Eugène Atget, Krauss questioned the validity of such concepts when applied to such a massive corpus. “There are other practices, other exhibits, in the archive that also test the applicability of the concept oeuvre. One of these is the body of work that is too meager for this notion; the other is the body that is too large. Can we imagine an oeuvre consisting of one work? The history of photography tries to do this with the single photographic effort ever produced by August Salzmann, a lone volume of archeological photographs (of great formal beauty), some portion of which are known to have been taken by his assistant. And, at the opposite extreme, can we imagine an oeuvre consisting of 10,000 works?” 1

In the case of Atget, Krauss’s arguments were intended not just to demonstrate the mis-fit between the tenets of art history as these are imposed on photographic history but also to interpret Atget’s production in terms of the organizing logic of the archive. For Krauss, this approach was supported by Atget’s own cataloguing system, which, as it turns out, answered to the categories and requirements of his various clienteles. And while it may be that this reading of Atget’s motivations, their logic, and embeddedness in use value (as opposed to exhibition value), are specific to Atget, the artistic, and indeed, epistemological issues, posed by enormous photographic archives have by no means been resolved.

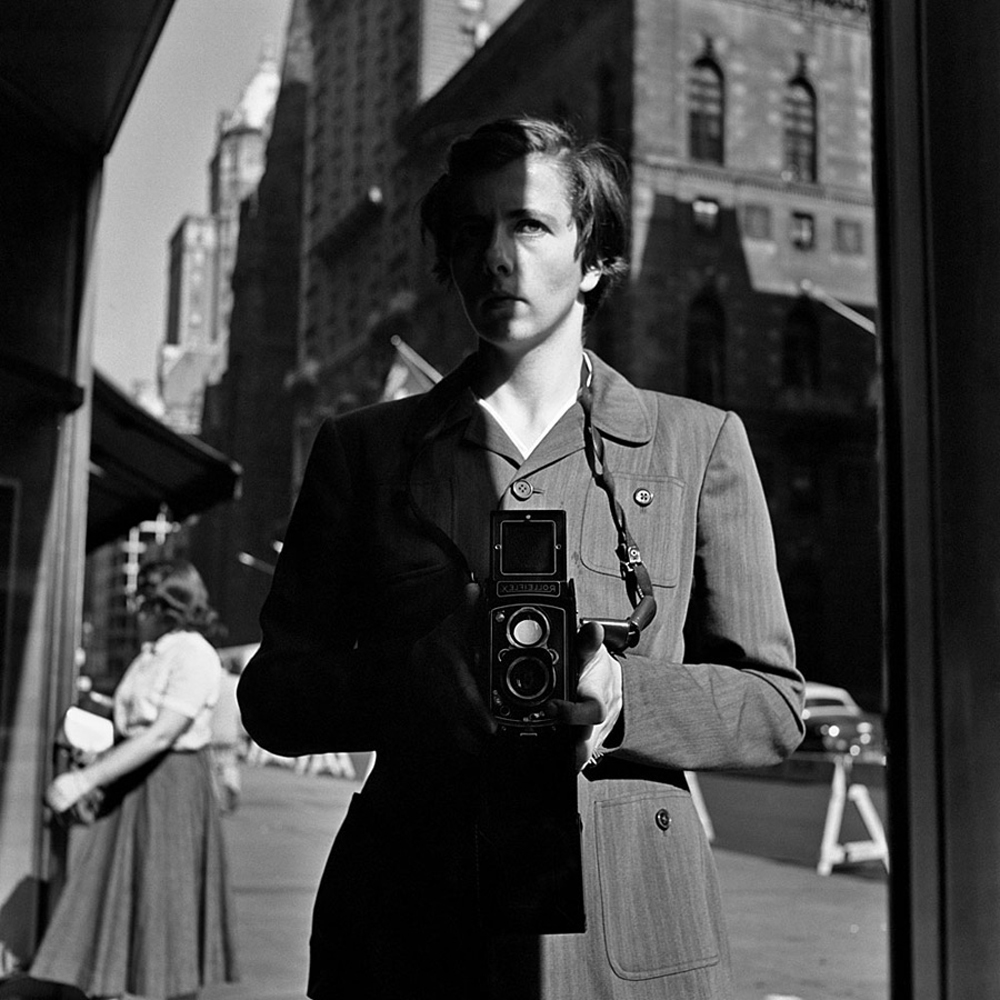

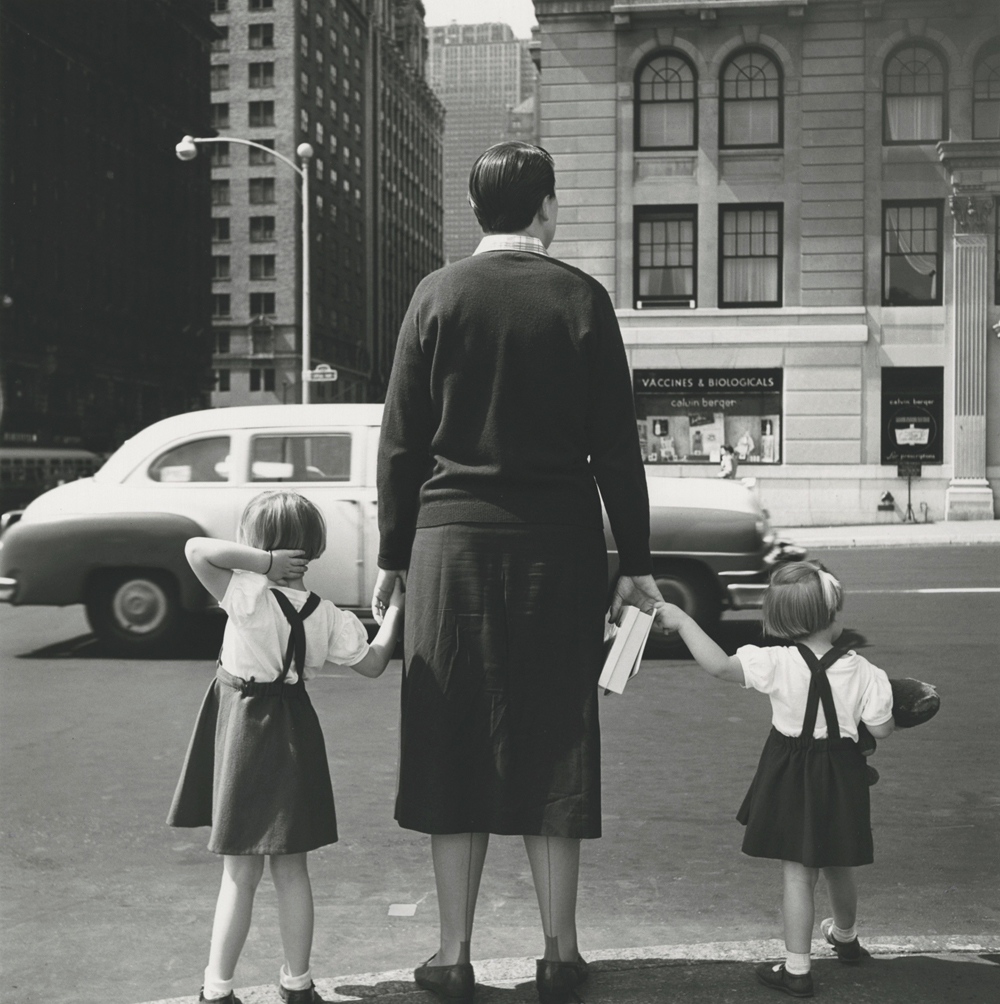

Vivian Maier, Chicago, IL, January 1956

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Thus, the recently excavated photographs, negatives, Super 8 films and videos made by Maier raises these questions and more. Few lives in the modern urban world have been lived so far under the radar as to produce barely a trace of the subject, even after diligent research. For most of her adult life, she worked as a nanny, governess or caregiver in the suburbs or towns around Chicago’s North Shore (ca 1956-1980s). She seems to have discarded nothing she ever possessed; among her effects beside the photographs were found clothing, shoes, old newspapers, books, albums, memorabilia, and – importantly – professional darkroom processing receipts. She never cashed in her tax reimbursements, becoming effectively indigent by 2007. Thus, and with respect to her now celebrated corpus, it was only when the contents of her storage lockers were auctioned off for nonpayment that the story of her discovery begins.

Born in 1926, from the late 1940s until some time in the 1980s, she photographed her surroundings and their inhabitants obsessively – there is no other word that adequately characterizes her enterprise. An elusive figure in virtually all respects, the facts of her life and work are gradually being reconstituted, a task involving genealogists, photographers, archivists, documentary filmmakers and other specialists. This itself attests to her obscurity and reclusiveness. After 1956, living always in the homes of her various employers, she nonetheless maintained a vigilant personal privacy, all the more astonishing for its separation from the bustling family life that surrounded her. With neither family nor friends, in her final years her sole financial support was provided by the Gensburg family, for whom she worked longest and who paid for her studio, In 2008, already elderly, she slipped on the ice and although she was expected to recover, after being moved into a nursing home, four months later she was dead.

It is therefore somewhat remarkable that so soon after her death, there are now two feature length documentary films, three monographs, several websites, some with short videos, and a growing number of collectors and commercial galleries all collectively functioning to catalogue, print, scan, publicize, exhibit or sell Maier’s work. 2 In other words, we are looking at the ongoing labor of many players, with various investments, all engaged in the process of manufacturing a reputation ab ovo. This is an extremely interesting process to observe, and in the context of my discussion here, it is not especially important if it is artistically merited or not.

Consequently, even as the biographical facts of Maier’s life are fleshed out, the central questions raised by Krauss are even more dramatically foregrounded given the scale of Maier’s extant archive. The collection of John Maloof consists of 100,000 to 150,000 negatives, over 3,000 prints, and also hundreds of undeveloped 35mm Ektachrome film. The collection of Jeffrey Goldstein, one of the purchasers of her auctioned effects, consists of 16,000 negatives, 225 rolls of film, 1,500 color slides, 1,100 vintage prints and 30 16mm home movies. 3 Ron Slattery has most of the original prints and some negatives. Goldstein has estimated that Maier produced about 50,000 images for each decade of her active life. 4 Only a small fraction of her negatives were ever printed, either by Maier (who for several years had used her bathroom as a darkroom) or later, her commercial printers.

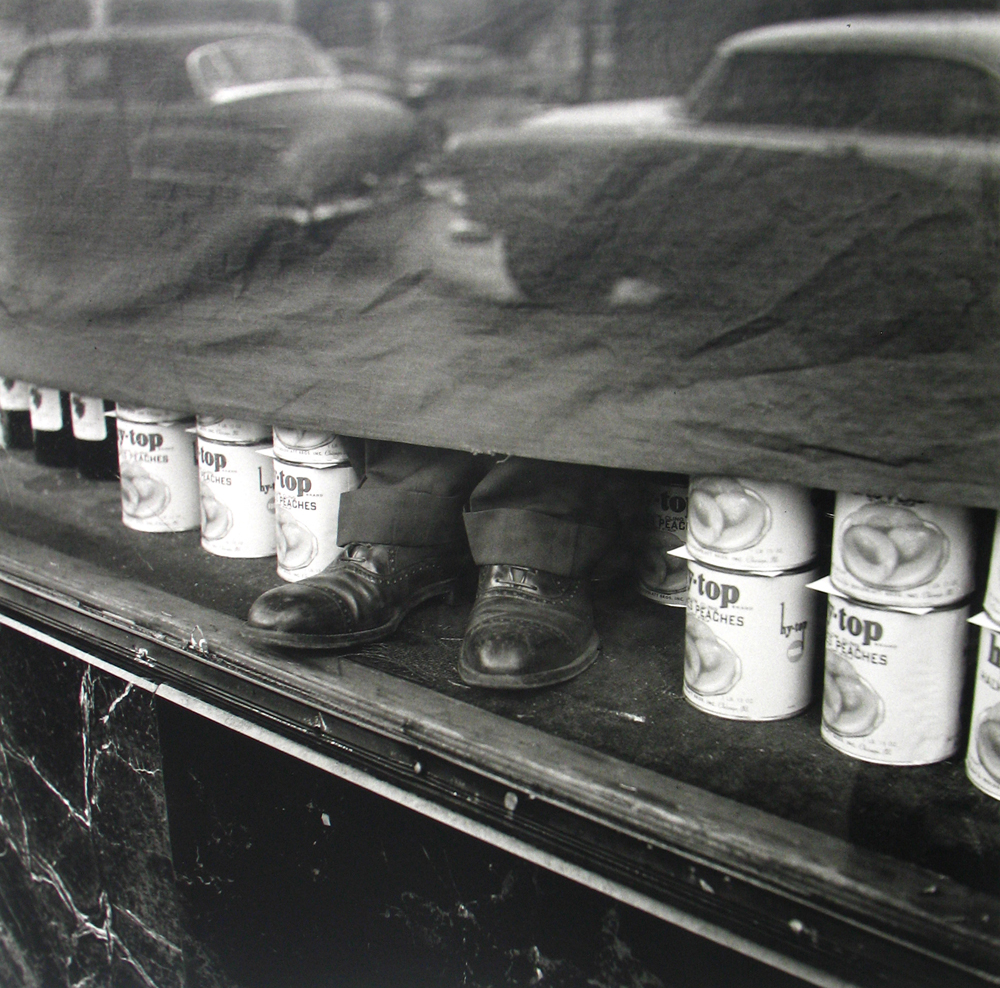

Vivian Maier, Chicago, August 22, 1956

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Inevitably and necessarily, what has thus far been reproduced or exhibited of Maier’s work has been selected, and often printed, by its various owners or, so to speak, its stakeholders. 5 This further begs the question of the definition of an oeuvre as expressing the preferences and choices – the presumed “vision” – of its maker. Putting aside for the moment all discussion of Maier’s subject matter, including the elastic definition of “street photography,” it is an open question as to how those photographs now printed from her negatives should look. 6 Joel Meyerowitz, one of the doyens of so-called street photography expressed his concern about how Maier’s work is being variously constructed, raising precisely this issue. 7 Obviously, there is no way of knowing why Maier printed (or developed) those that she did, or how she would have printed those that remained undeveloped. Moreover, at least in certain cases she cropped her prints, although as with virtually all her photographs, these were intended for her eyes-only. The sole exception to the privacy with which she guarded her photographic production was her occasional sale of pictures to the parents of the children who were in her charge.

Without endorsing the fetishism of certain types of photographic connoisseurship, it is nevertheless the case that choices in printing, cropping, and paper do materially affect the appearance of photographs, especially in black and white. This is equally the case with book or catalogue reproductions, as can be readily seen by comparing the reproductions in Maloof’s Vivian Maier: Street Photographer and Richard Cahan and Michael Williams’ Vivian Maier: Out of the Shadows. Those in the Maloof book were printed from high quality scans of the negatives, and are crisper, sharper and more tonal. They are full-page reproductions but not full-page bleeds, as are many of those reproduced in the Richard Cahan and Michael Williams catalogue. Which of the photographs are more accurate or faithful to the negative is impossible to judge, and thus it is only the (relatively) limited numbers of the prints she made that might provide some sense of her own preferences. But what if the prints made by scans or reprinting from her negatives are markedly of far “better” quality than the ones she made herself? (I would suspect this will turn out to be the case; had Maier been concerned with the quality of her prints there would be many more of them). Inescapably, the questions that arise with the posthumous reconstruction of a photographic reputation reveal contradictions and conundrums that are only distantly related to the art history of printmaking, but are endemic to the fabrication of photographic histories.

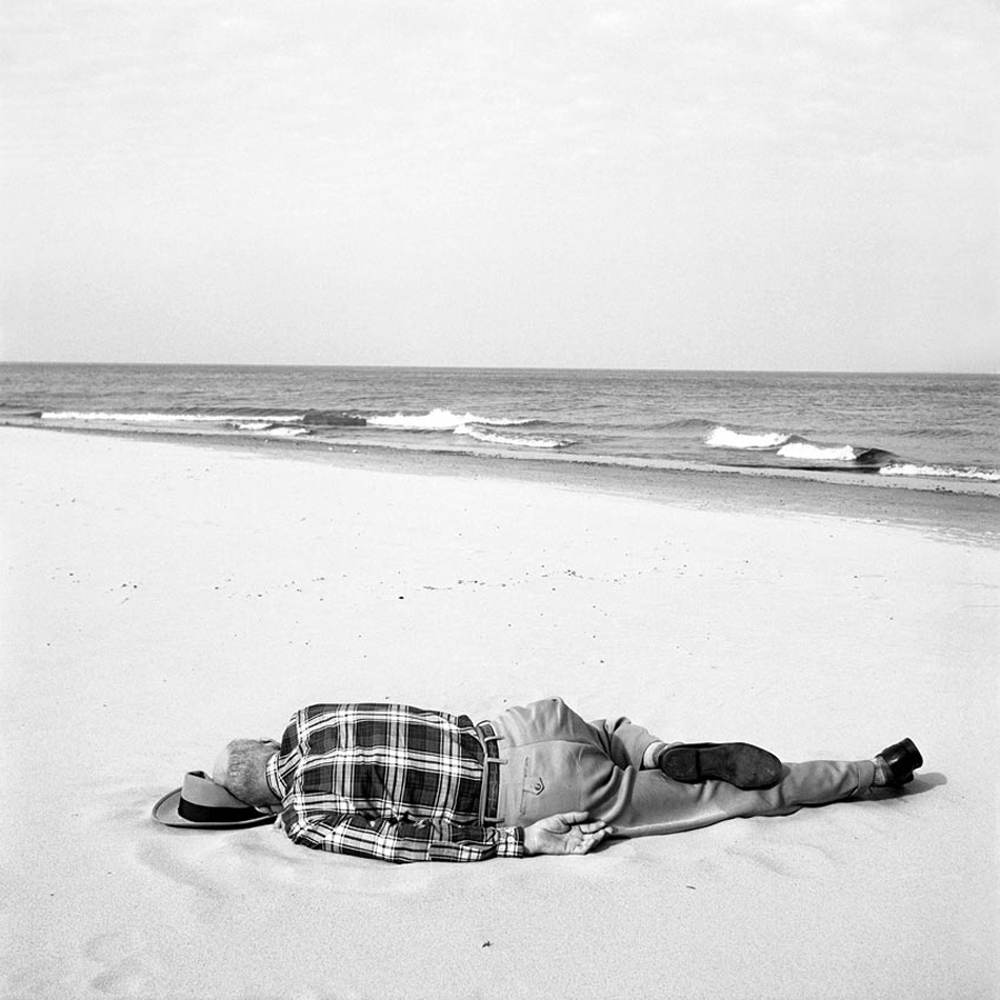

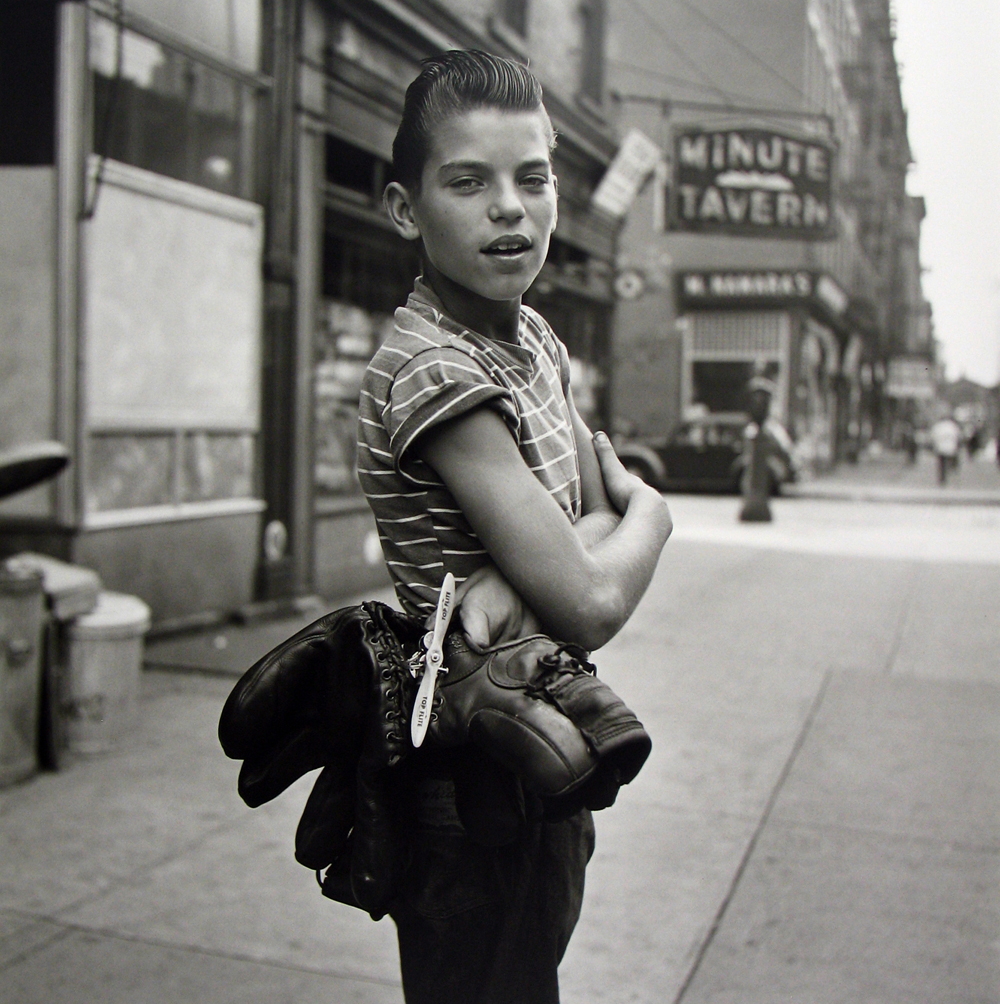

Vivian Maier, St. East nº108, New York, NY, September 28, 1959

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

I have written elsewhere about the dubious generic category of “street photography,” a category so capacious as to be effectively meaningless. 8 While there exist hundreds, if not thousands of photographers, many anonymous, who have made pictures on the street since photography’s earliest years (and for many different reasons and purposes), this does not in and of itself constitute a coherent genre. As a term invented in the mid-twentieth century within art photography discourse, the notion of “street photography” has been deployed to consecrate work by a very limited number of [mostly] art photographers (Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank are paradigmatic examples). Be that as it may, among the ranks of those taking pictures of passers-by in public space, the number of women to have done this is significantly rare. 9 In this respect, one of the most remarkable aspects of Maier as, in a sense, a compulsive photographer, is her gender. Certain of Maier’s commentators have invoked the precedents of Lisette Model and Helen Levitt as soi-disant street photographers, both of whose works Maier may well have known. 10 Nevertheless, many if not most of Model’s published photographs are oriented towards the grotesque, and Levitt mostly photographed neighborhood children.

Vivian Maier, Untitled, 1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In any event, despite her distance from photography as a métier, Maier’s life-long picture taking, made primarily in public space, was anything but the hobby of an amateur, despite its private motivation. To what extent this was a function of her asocial existence, her extreme eccentricity, her apparent asexuality, who can say? Like so much else of Maier’s life and work, this is not an answerable question. What one can say is that in some mysterious and indeed, poignant way, Maier lived her adult life through the camera’s lens, a vicarious life in which the camera “eye” and the subjective “I” were inextricably linked. I know of no such other example in the history of photography. But an important point to be made is that like photojournalism, photographing on the street is a quintessentially masculine preserve. The reasons for this are many, and include the masculine prerogatives of active looking, the gendered attributes of public space, the relative vulnerability of women within that space, and the aggressive aspects of photographing unwitting subjects.

Vivian Maier, New York, NY, 1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Accordingly, sexual difference, as well as gender — both inescapable facts of human psychic and social existence — cannot be immaterial or irrelevant in Maier’s photographic practice. It may have determined how she photographed (the Rolleiflex is far more discreet than a camera held to the eye); what she photographed (much of her subject matter is of suburban children at play) and shaped the way she imaged herself as an isolated figure disconnected from other human beings. Be that as it may, and in keeping with her employment, one major aspect of her work from the 1950s is the way she recorded the life of children (her charges included) without sentimentality or condensation. Depicted in parks and schoolyards, her [white] children in well-to-do suburbs of the North Shore are interestingly paralleled by her pictures of inner-city children of color and adults, as well as the working class, the poor, and the down-and-out. These raise interesting questions as to how and why this Franco-American, spinsterish woman would be so drawn to the urban margins: voyeurism? curiosity? empathy? identification? Reference is made by some of her previous employers (notably the Gensburgs) to her espousal of “liberal” or “left” politics, but no real details are supplied. Moreover, to have photographed then Vice President Richard Nixon greeting crowds in Chicago, or photographed newspaper headlines about John and later Robert Kennedy’s assassination are not indices of any particular political orientation. Apparently, there exist many photographs made during her extensive international travels, which included South Asia, the Philippines, Cuba, Egypt and many other places, but few of these have been published or exhibited. If nothing else, these far-flung voyages during which as always, she photographed constantly, suggest that she was utterly fearless. (In the 1950s, few women alone would have hazarded such journeys just as they would have avoided the Bowery or Chicago slums).

Although the relatively limited numbers of her pictures so far available make generalizations highly speculative, there are aspects of her photographic trajectoire that signal how it may have evolved. Her earliest extant photographs were those made after she and her French mother returned in 1932 to her mother’s natal village in the French alpine valley of Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur. Prior to their return, and after Maier’s mother’s separation from her husband Charles Maier (an émigré Austrian), the two had lived in the Bronx with a portrait photographer named Jeanne Bertrand. Whether Bertrand and her profession had any bearing on Maier’s future activities, as a photographer is, yet again, unknowable. 11 As with many outsider artists or photographers — that is, those outside either professional or artistic practice — reconstituting a life is more difficult than reconstituting an archive.

In Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur, employing a Brownie box camera, Maier produced her first photographs. From what has been so far reproduced, these are unremarkable pictures of the Alpine scenery and the residents of the village. It seems evident, however, that when photographing these subjects, she was within a familiar milieu, her pictures made with the cooperation of her subjects. In 1938, she and her mother returned to NYC. But in 1949, at 23, Maier returned to Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur to claim a legacy from the sale of a family property. The proceeds enabled her first independent travels in the south of France.

In her passport application of 1950, Maier described herself as a factory worker, and by 1951 she was evidently employed in a sweatshop. According to Pamela Bannos, a photographer teaching at Northwestern engaged by Maloof to help determine the material and technical aspects of her work, sometime between 1951 and 1953, Maier replaced her basic box camera with a medium format twin lens Rolleiflex. The Rolleiflex produces two and a quarter inch square negatives, twelve exposures to a roll of film. Aside from the square format of the negative (which in turn influences an image’s formal composition), the exposure is made as the photographer looks down to the viewfinder where the image appears reversed. It may have taken her some time to master this more complicated camera, insofar as there is apparently a lacuna in her photography for the year 1952. But by 1953 she was using the Rolleiflex nearly exclusively. 12 One of the other characteristics of this camera is that the making of the exposure requires no eye contact with the subject. Once the exposure is set, the photographer could be looking anywhere, and as such, the subject on the street may be altogether unaware of their visual capture. Indeed, in many of the self-portraits Maier looks up, sideways or frontally, the camera remains always at chest level.

Vivian Maier, Untitled, September 3, 1954

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In those pictures where her subject is clearly aware of the camera and willing to be photographed, they are overwhelmingly children, the elderly, minority or marginal adults (e.g., skid row denizens, the very poor, etc.). This is not unproblematic. Although photography critics and historians frequently babble on about humanism, empathetic identification and other alibis for both “street photography” and documentary, at least since Martha Rosler’s classic essay of 1981 there has existed a rigorous critique of the implications of posing the camera downwards. 13 In other words, issues of power, of subject-object relations, and exploitation, as well as those of class, are inescapable aspects of what might be called the ethics as well as the politics of photographic representation. How or should we consider Maier’s practice in relation to such issues?

Of what has thus far been seen of Maier’s pictures, there appear to be few pictures of beautiful women or handsome men (there are some exceptions, but they are exceptions, unless this itself reflects editorial choices). On the other hand, there are many pictures of unconscious subjects (as well as unwitting ones), many back views, and many fragments of bodies. This suggests a gendered position inasmuch as it takes certain assertiveness, if not aggression, to photograph people without their permission. The expression of affront or annoyance on the face of certain of the bourgeois elderly women in Maier’s pictures makes evident their displeasure at being so taken, as it were, off guard. One of the camera shop employees where Maier processed her film remarks that she didn’t like women who were “made-up,” or “too feminine.” 14 Thus, while certain of her photographic subjects can be said to be participating in a social transaction, there are also numerous instances of what Henri Cartier-Bresson characterized as the camera’s “pounce.”

Vivian Maier, New York, NY, c. 1953

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Here we might distinguish between her self-portraits and her self-representation, for while all portraits are self-representations, not all self-representations are portraits. Specifically, I refer here to the many photographs in which her unmistakable shadow looms across the scene before her viewfinder. This is, as is well known, a recurring trope in modernist photography; indeed, Lee Friedlander produced an entire book around this device. Which in turn suggests that Maier had been much more aware of the photography of her contemporaries than is acknowledged. Among her archives are a number of photography books, and during her many visits to NYC, she could well have popped into MoMA, where photography was continually exhibited. Perhaps the assumption of her unfamiliarity with contemporary work, even ignorance of it, is thought to burnish her reputation further. As for the self-portraits, it is their implacable opacity, and occasionally striking formal invention that place them into a different category than the more conventional imagery she made in the street.

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, undated

© Vivian Maier / Maloof Collection. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

As of today, (2 September 2013) a new story about Maier’s work has emerged from the blogosphere. It appears that even as what Jeff Goldstein referred to as the “Vivian Maier business” appears to prosper, there exist potential legal issues around copyright law. According to her post entitled “The Curious Case of Vivian Maier’s Copyright” by Julia Gray, it is possible (although evidently unlikely) that the state of Illinois could claim at least some of the profits from the sale of Maier’s archival prints or reprints from her negatives. The gist of which is that the state of Illinois might have claims on the sale of her prints and reprints of her photographs. Having died intestate, normally all her belongings or property would go to relatives no matter how far distant. Absent these, it would revert to the state. But the situation is extremely complicated legally; especially because the contents of the storage lockers were purchased while she still lived (2007). Consequently, Grey describes multiple scenarios, although all are predicated on the willingness of the state to prosecute the current owners or stakeholders. One option, Gray writes, is that “the state could decide that instead of a cease and desist order, the current owners may continue selling her work but that royalties would be collected by the state. In this instance, the state could pit the owners against each other, depending on who will pay the state more royalty money. Finally, if the current owners don’t cooperate, the state could sue them in federal court for ownership. However, before a lawsuit could proceed, the state would have to obtain the copyright.” However, the probate papers do not mention what is called intellectual property — the copyright on both printed and unprinted photos. Nor is there any copyright of her work registered with the United States Copyright Office. All of which suggests that it is unlikely there will be any real consequences for those involved with the Maier enterprise. Which is by no means to imply that this would be a desirable outcome. But it is here, however, where one can see how the terms of an “aesthetic” discourse within the world of contemporary photography, turning on the individual author and her work, and the far less lofty realities of market and marketing, property relations, public relations, media relations and all the other apparatuses, illuminate one another, or even collide. “Her big project,” remarks Michael Williams, “was her life,” but perhaps the even larger project is her posthumous invention.

Abigail Solomon-Godeau, 2013

Exhibition « Vivian Maier (1926-2009), une photographe révélée », from 11/09/2013 to 06/01/2014, at Château de Tours, organized by Jeu de Paume and produced by diChroma photography.

References