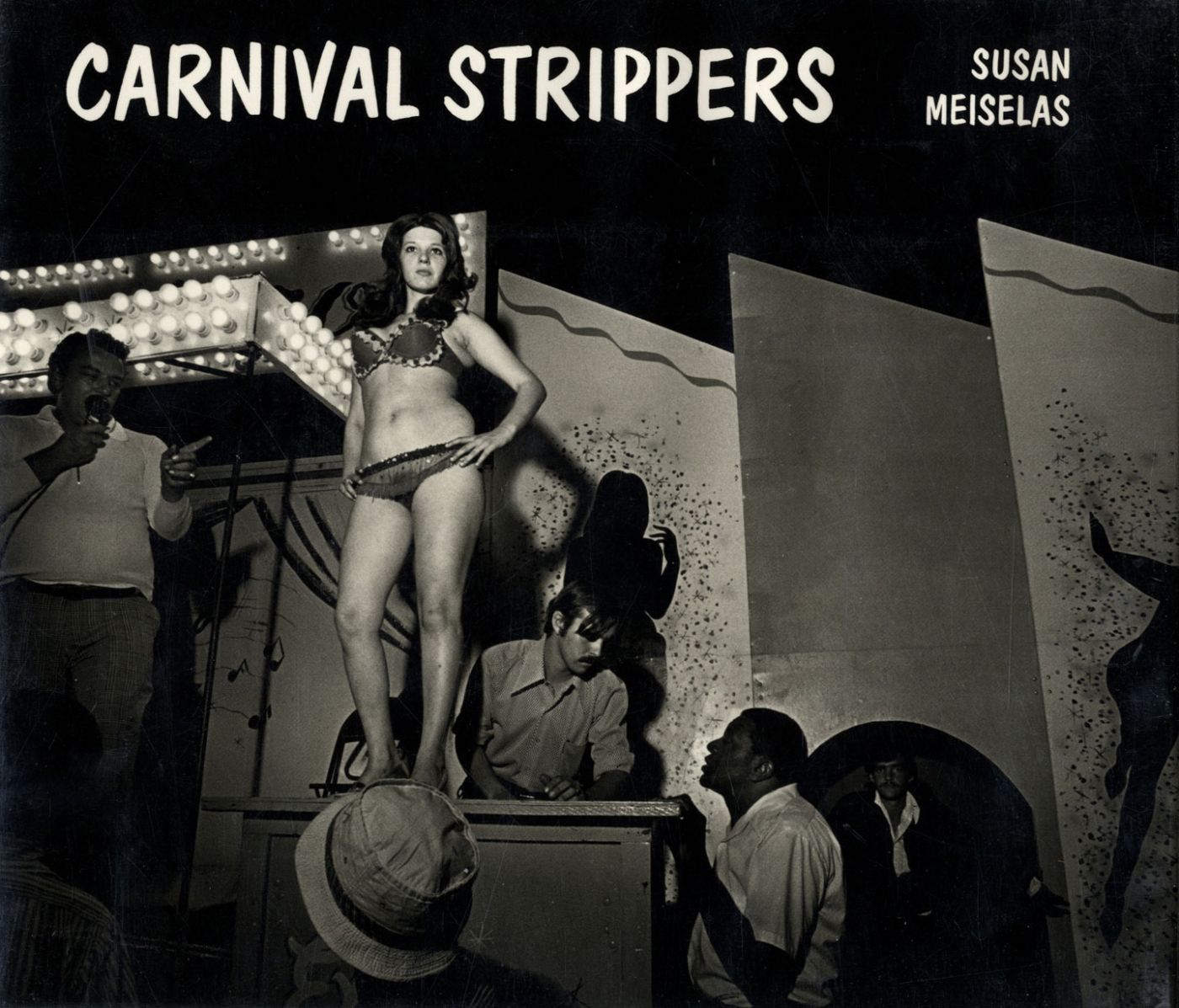

In 1976, Susan Meiselas published a book on the women working at a carnival striptease show travelling across the American Northeast. Her black and white photos not only revealed the reality behind the glitter, but also showed the day-to-day life of these carnival strippers. Their profession was, by removing their clothes, to sell their image the time of an evening. So much more than a display of glamorous or sordid images, Susan Meiselas’ work provided a glimpse, a more raw and intimate vision of the women’s lives. Not only that, she chose to include their voices and record their accounts of their lives, thereby breaking through their confinement within an image.

This long-term project would open the doors of Magnum Photos, a co-operative founded in 1947 by a group of famous photographers, not the least of whom were Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. The members of this select agency were most probably won over by Meiselas’ subtle approach, which challenged the sensationalist, titillating way of treating such subjects at the time. Thanks to Magnum, Susan Meiselas’ work was sent out to more potential clients, in particular to magazines. In fact the co-operative sent what it called “distributions” to its network of agents and clients. These took the form of reportages comprising a series of photos with accompanying captions and texts that could easily be inserted into the pages of weekly magazines. Selecting the best images, organising them into a sequence and providing precise texts to go with them was a way of telling a “story” with just a few photos: the resulting story was then sold to the highest bidder. This art of visual narration or storytelling was an inspirational training for many of the agency members, who learnt the ins and outs of photojournalism. Susan Meiselas hadn’t studied journalism, having received a visual education. She gradually took on board the rules of the profession, whilst preserving her commitment to using images as a point of connection to people, as she had done since her student years.

Pushing back the boundaries of the photographic profession

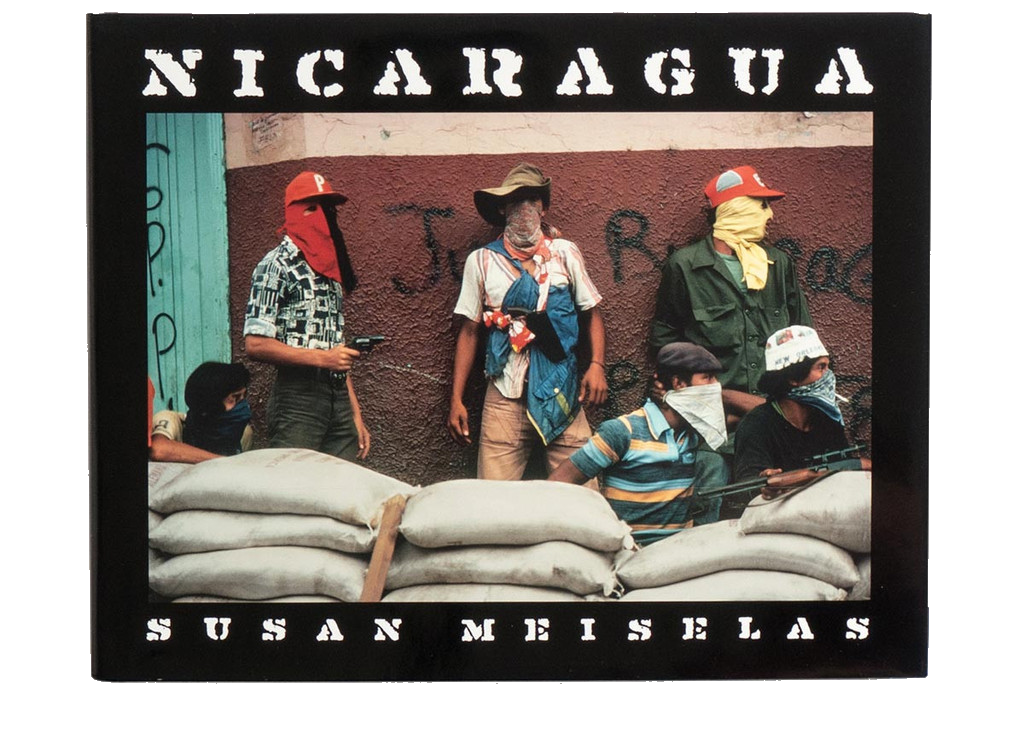

At the end of the 1970s, Susan Meiselas set off to cover the evolving social conflict in Nicaragua and found herself in the middle of the insurrection, taking some of the most widely distributed images of the conflict. Her vivid photos became icons of the revolution and were republished to mark anniversaries and printed on posters. Abundantly reproduced, these images gradually lost any precise notion of context: who were the people in the photos and why did they take part in the fighting? Nobody could remember. In light of this media success, Susan Meiselas decided to put her images back in their original concrete, local context. Ten years later, she returned to Nicaragua to find the people in the photos and speak with them. In 2004, she exhibited the photos in the very places they were taken, filming the reactions of passers-by. For her, the natural prolongation of her work as a photographer was in this dialogue with the communities at the origin of the images. By her actions, she broke with the relationship of dominance in which the photographer “takes” photos of subjects, sometimes against their wishes and endeavoured to “return” part of her work to the men and women who gave rise to it. Already Susan Meiselas was adopting the role of a “transmitter” of images and creating a point of contact between communities – the ones she came into contact with in the field and the communities of people who would look at these images once they had been made public.

Susan Meiselas, Installation of a photo of the August 1978 insurrection in the very place where it was taken. Matagalpa, Nicaragua, “Reframing History”, 2004 ©Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos

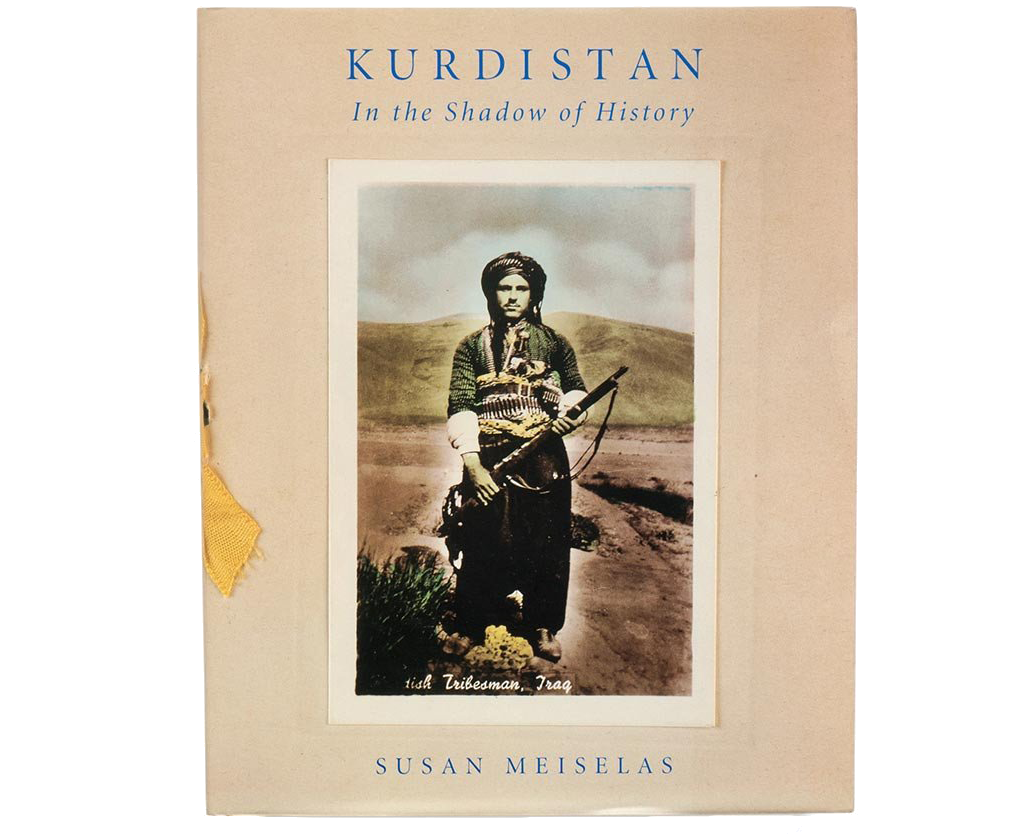

Throughout the 1980s, she continued to push back the boundaries of the traditional role of a reporter, by working as both a photographer and a film director. She also worked with other photographers, mainly in Central and Latin America. In 1990, she published a book with a collection of photos taken by Chilean photographers during the Pinochet regime. Between 1991 and 1997, she set herself a colossal task with her akaKurdistan project, which comprised a travelling exhibition, a collaborative website and a book assembling the photographic heritage of the Kurdish people, together with their individual stories. Successively an exhibition curator, an archivist, a film director and an author, Susan Meiselas made sure to use images as a way of forging connections between people. At the time, some members of Magnum didn’t entirely understand her Kurdish project, seeing how she had abandoned her work as a photographer to present images taken by others. Today this pioneering project is a model example of a collaborative and archival approach, one that is followed by numerous photographers and artists who have decided to go down this path. 1

Susan Meiselas, Kurdistan. In the Shadow of History, Random House, 1997, republished by University of Chicago Press, 2008

And yet Susan Meiselas wasn’t isolated at Magnum, whose members shared a common refusal to let themselves be stuck in rigid and unchanging roles. They all experimented in different fields, from documentaries to advertising and from fashion to corporate commissions, not forgetting books, films and exhibitions. There were other photographer/film directors in the collective, Raymond Depardon to start with, as well as several other authors looking to combine their work with a social or political commitment, hoping to convey an in-depth account of a situation and to stand out amongst the mass of press and amateur images. One such example was Danny Lyon who, in 1971, published a book of photos on the Texan prison system that had a collaborative and archival dimension in the way it presented an inmate’s letters and drawings alongside the images. Since the end of the 1970s, Jim Goldberg had also been developing another way of dialoguing with his subjects by inviting them to write their impressions and comments directly on the photos.

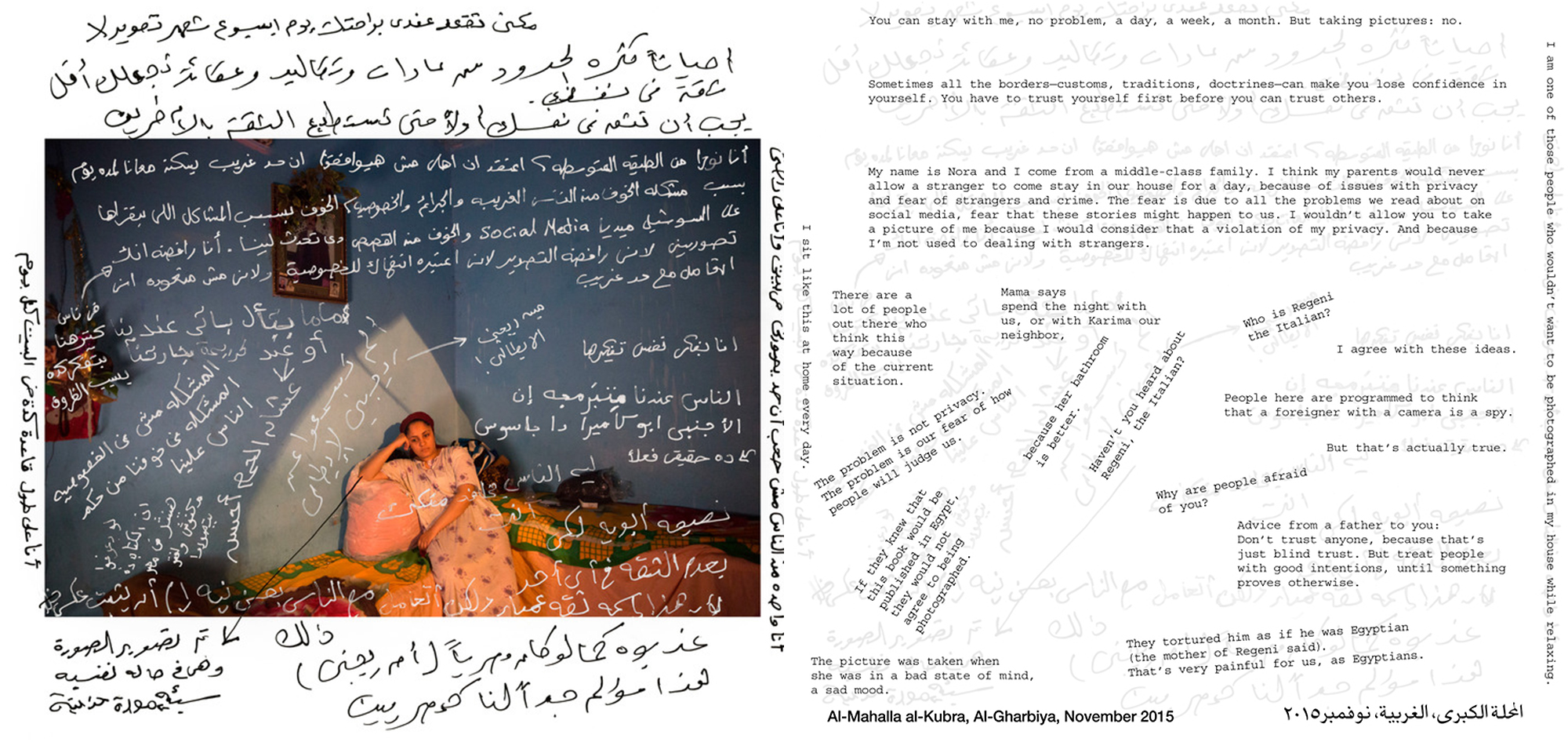

Goldberg’s process is reminiscent of a more recent project by the young Belgian photographer, Bieke Depoorter, who joined the co-operative in 2012. Bieke usually works at night, finding people to put her up in the course of her wanderings. After recently crossing Egypt spending each night in the homes of local people, she prepared a first draft of her book with the images she had brought back. She then returned to Egypt and asked different people – i.e. not the ones who actually appeared in the original images – to share their comments on the photos. Each double-page spread in the book therefore becomes a place where the photographer’s vision and the faces of the people in the photos encounter the reactions of readers who have been invited to give their first impressions. These annotations – personal, critical or funny – frame the images, sometimes using an arrow to indicate they are answering another comment. Bieke Depoorter decided to publish her book as is, with its images literally covered with handwritten remarks. The book’s French title is Mumkin2. The term corresponds to the first words of the sentence in Arabic for asking permission to take someone’s photo: “Can I?” The answer to this question begins with the agreement given by the subject and finishes when the photographer returns on location and shares the results of her work with a third party; witnesses and participants who take part in the conversation, thereby acknowledging the possibility that one can debate by means of images. Bieke Depoorter also positions herself as a “transmitter” of images and holds up Susan Meiselas as an example3. She showed her this recent project and remembers feeling very touched when they were able to discuss her work in 2010, at a time when she had just finished her studies and wasn’t really sure about embarking on a career as a photographer.

Bieke Depoorter, Egypt, 2013, annotations from November 2015, Al-Mahalla al-Kubra, image published in As it may be, Aperture, Hannibal Publishing / Mumkin, Est-ce possible ?, Xavier Barral, 2017, together with a booklet that included a translation of the texts © Bieke Depoorter / Magnum Photos

Creative communities

Susan Meiselas is still committed to helping young photographers and students by being available to help and give advice. This is another facet of her role as a “transmitter”. She became the first president of the Magnum Foundation which she helped create in 2007. Today the Foundation works with human rights organisations and widens the scope of documentary photography by working with women, students and both amateur and professional photographers from other parts of the world, such as the Middle East, Colombia and China. It provides them with financial, professional and creative support and organises debates and workshops based on the premise that a documentary should be a collective work, one that gains from exchange. Susan Meiselas takes a very active role in the Magnum cooperative, supports young authors and still deeply believes in the fruitful nature of exchange and communities. This notion of community of which American culture is so fond, has fashioned her body of work, which was fostered by the debates about the photographic profession within Magnum itself and structured in contact with groups whose identities were either in flux, imagined, asserted or endured. Inspired by her experiences with archival projects, Susan Meiselas and the Magnum Foundation also endeavour to collect documents bearing witness to the photo agency’s history and organised a series of interviews with key figures from the world of photography with an aim to preserving their collective memory.

Looking to the past and sharing experiences, but also looking to the future by educating the new generations, Susan Meiselas is therefore also a “transmitter” between the older and the younger generations, envisioning the Magnum Foundation as a place where things are passed on.

Susan Meiselas, “A Room of Their Own”, At play in communal kitchen, a refuge in the Black Country, UK 2016 ©Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos

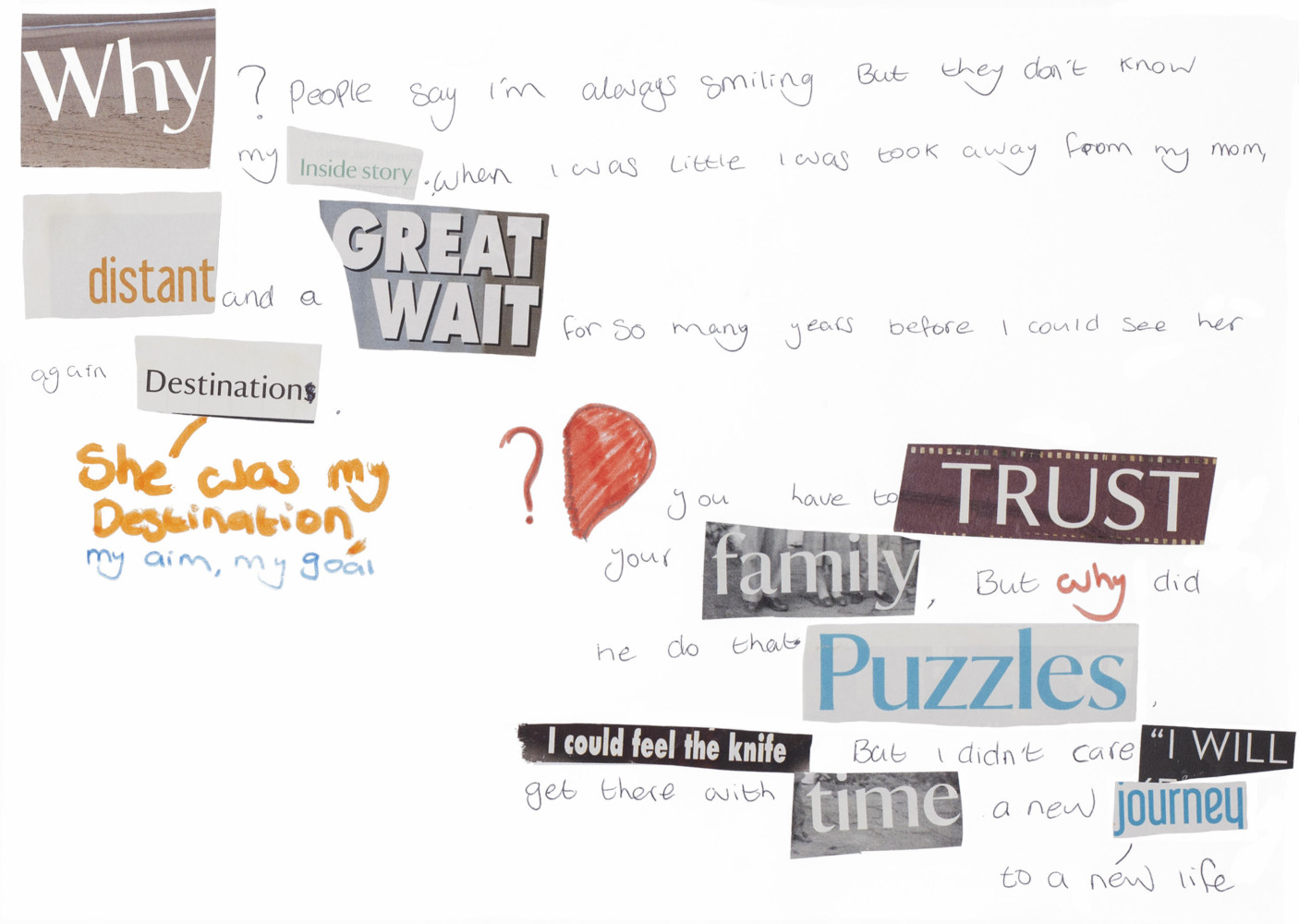

Her latest book is named after an essay by Virginia Woolf, ‘A Room of One’s Own’, which questions women’s lack of recognition in literature and the fact they do not even have the necessary material conditions to express their creativity – i.e. not even a room of their own to work in. Meiselas’s book is about a woman’s refuge for victims of domestic violence in the West Midlands (England). It is the fruit of writing and photography workshops organised with the women living in the shelter and the meals they prepared and cooked together. The photos, from which the women themselves are often absent, comprise nevertheless their implicit portrait. There are very few faces to be seen, but in their place are photos of bedrooms, day-to-day life with children, the stories of the women’s lives and their collages like so many fragments of this place “of their own” where women can finally speak out.

Clara Bouveresse, 2018

Translation: Simon Thurston

Homepage : Photograph by Susan Meiselas, Muchachos await counterattack by the Guard, Matagalpa, Nicaragua, 1978 © Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Sam’s Collage, A Room of Their Own », in collaboration with Multistory, 2016 © Multistory

Biography

Clara Bouveresse is an art historian specialising in photography with a PhD in art history from Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University. She wrote Histoire de l’agence Magnum. L’art d’être photographe (published by Flammarion) based on her on her thesis. In 2017, she co-curated Magnum Manifesto, Clément Chéroux’s exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York marking the photo agency’s 70th anniversary and also co-wrote the exhibition catalogue that was published in five languages. Her article on Susan Meiselas’ Kurdistan project was published in Transatlantica. In 2014-2015, she received a Georges Lurcy fellowship to pursue her research at the University of Columbia (New York).

“Susan Meiselas, Mediations” at Jeu de Paume, Paris

Paris Photo / Interview of the artist

Susan Meiselas

Bieke Depoorter

References