In recent years, an admonishing view has emerged in an ordinarily bland genre: the photography of nature. One glance at the field tells us that ecological concerns, understandably enough at this historical point, have infiltrated the medium. How can they be expressed effectively? How can they be responded to? What do they tell us about our culture?

Nicolas Poussin, Les Bergers d’Arcadie (Et in Arcadia ego), 1637-1638

Courtesy The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei, 2002.

As a craft nature photography is specialized, requiring particular tools. Only a big view camera, for instance, has the range to thrust deep into a landscape, restoring to a picture surface remote detail that a smaller instrument would interpret only as tone. In a grand horizon one expects both texture and tone, or rather texture within tone. A large-format print allows a panorama to be backed up by what seems to be an endless reserve of data. This discriminative power is just as well, for the scene is likely to be devoid of a main incident. What we generally have in landscape photography is a kind of micro-nutrition—based on diffuse vegetarian ingredients—that compensates for a lack of psychological narrative and a visual center.

Such a peaceful, almost comatose state of affairs has recently been ruffled by a wave of activism. Pictorially, the chief but also misleading forebear of this would be the Frensh paysage moralisé, a landscape genre which, either by reflecting our passions or inducing some philosophical meditation on life, drives home a moral. We do not just contemplate the goodness of the place but find it an object lesson derived from its pictorial appearance. About Nicolas Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego (ca. 1640, Louvre, Paris), a famous moralized landscape, the poet Théophile Gautier wrote, “The picture of the Shepherds of Arcady expresses with a naïve melancholy the brevity of life and awakens among the young Shepherds and the girl who look at the tomb they have found, the forgotten idea of death.” Arcadia, the ideal of the pastoral tradition, here represents that strangely lovely moment when figures in a landscape uncover evidence of an ancient happiness and a witness to our moral destiny. Gautier could call this a “naive” melancholy because he lived in the already stressed-out, coal-blackened nineteenth century.

In a postpastoral version of that melancholy, the picture of nature today may testify to the damage men have done to their environment, a damage possibly so extreme as to hasten human and animal fate. With both the earlier moralizing tradition and the current instance of it, landscape is conceived as an artifact of culture. But unlike its predecessor, the present culture leaves new traces of disorder and anomaly within the old landscape construct. We glimpse a prelude to a future that once was inconceivable but now may not even be remote: the irrevocable extinction of certain living things. The pastoral tradition had been expressive in its awareness of the natural cycle in which death and birth replace each other. Now, instead of discovering the ephemerality of sensate life in an enduring scene of beauty, the viewer must face the fragility of the scene itself—a tableau of repulsive contingencies that do not strike us as either culture or nature.

Richard Misrach, Bomb Destroyed Vehicles and Lone Rock, 1987. From Bravo 20: The Bombing of the American West © Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

This ambiguity, though it has quite a literary and pictorial background, is the product of something we are just beginning to recognize. Artists have always liked to depict fringes, blurred borders, and vague terrains. They may have thought of them as truly mysterious regions or unregarded banalities, but in either case the prevalence of such scenes impresses them now. In some of today’s landscape photography, dubious surroundings reflect a kind of unthoughtful contemporary experience. Everything runs into everything else in a manner that exhausts anyone’s power of discerning cause and effect. Put differently, a sifting occurs whereby territories come to seem palpably other than—often subtly the opposite of—what they had been. Without being to any human advantage (though activated by humans), phenomena migrate to the wrong place, as do toxic gases that escape into the air. Observing such unlikely fusions, we perceive what in information theory would be called noise and what in common terms is spoken of as dirt.

“Wrongness” on this level is obviously a relative measure. It implies a contrast to what organisms want or where they need to be to maintain the conditions, systems, and functions of life. The contrast summons up what we fear: interference to patterns of natural replenishment. Here, “wrongness” is a more difficult notion to understand than, say, incongruity —things going inappropriately together— a state of affairs that often describes heterogeneous arrangements, natural or cultural. Surrealism has given us a taste for some of these phenomena, which can offer surprise and therefore new information. But generally speaking, the incongruous has no fatality about it. We are accustomed to the depiction of American townscapes or rural scenes with mildly clashing features. But we do not think of them as “wrong” in the same way that symptoms indicate something is wrong to doctors. This symptomatology has become a subject of some recent American landscape photographs.

In theory, one way to observe that subject is via aerial camera or one traveling in space. Recent NASA photography of one of Neptune’s moons revealed inexplicable markings that have nonplussed science. These phenomena may have originated in events that were singular or even abnormal but were hardly unnatural. On earth, categories that define natural or unnatural exist for us as products of our own culture. Even so, at some altitudes, it is still often difficult to separate human-made from natural conditions in the biosphere. For example, after many years of photographing the earth from planes, Swiss scientist Georg Gerster published the results in a book called Grand Design (1976). He was able to show a phenomenon like red tide in a Japanese bay without attributing it to human interference, as was obvious in his images of aluminum poisoning of Australian trees or oil and tar residues along the Ivory Coast. While the view from above certainly revealed a very dynamic and fragile ecosystem, it did not deflect Gerster from stating that “man’s dilemma —to change nature or adapt himself to it— is insoluble…. It is Man’s earth…. The right of codetermination for wild animals? Partnership with all creatures? … Fashionable models, all but foolish ones.”

Gerster did not then question our priority as a species, but our understanding now begins to suggest that partnership with animals is an enlightened rather than a foolish idea. Yet one would be hard-pressed to read this just from the perspective of aerial photography, for the wrong spots, when they exist and are interpretable, are also coded by distance. Either specialized knowledge or explanatory texts are needed to disclose such a pathology, like that possessed by a doctor incriminating an otherwise nondescript white area in an X-ray.

David T. Hanson, Excavation, Deforestation and Waste Pond, 1984, from the series Colstrip, Montana 1982-85. © David T. Hanson

A young photographer, David Taverner Hanson, has brought to his aerial photography a decidedly clinical tone that depends on a kind of color coding. He has flown repeatedly over the Montana Power plant at Colstrip and has picked out alien presences there: chemical deposits left from operations and mine tailings that show up as strident dyes draining into sandy, torn ground. Though these acidic hues immediately tell us that something is amiss, they are in themselves no more than splotches in an abstract topography, reminiscent of illustrations in fractal geometrics. We have to appreciate the sensory impression as an outcome of processes reported in the mineralogical analyses with which Hanson sometimes accompanies his pictures. Their moralizing is inevitably ex post facto. These delicately or weirdly colored photographs may have an impact, but it is delayed and finally dissociated from its cause. Such imagery works as an act of certain witness, at a remove that disconnects us from the actual hazards it describes, even as it uniquely situates them. The greater the visual perspective, the more it requires a narrative —for example, the history of a company’s failure to observe safety regulations— to account for the jumbled photographic spectacle. In the end, narrative tells the main story, of which the pictures are but an elegant, puzzlelike confirmation.

David T. Hanson, California Gulch, Leadville, Colorado, 1986. From the series Waste Land, 1986-1989 © David T. Hanson

On the ground, the photographer may face or actually choose the problem of being too close to the wrongness of an environment and therefore resist a narrative reading. It seems unlikely that the internationally known Lewis Baltz conducted himself that way except in long-term recoil against the prevailing sentimental or heroic genres of landscape.

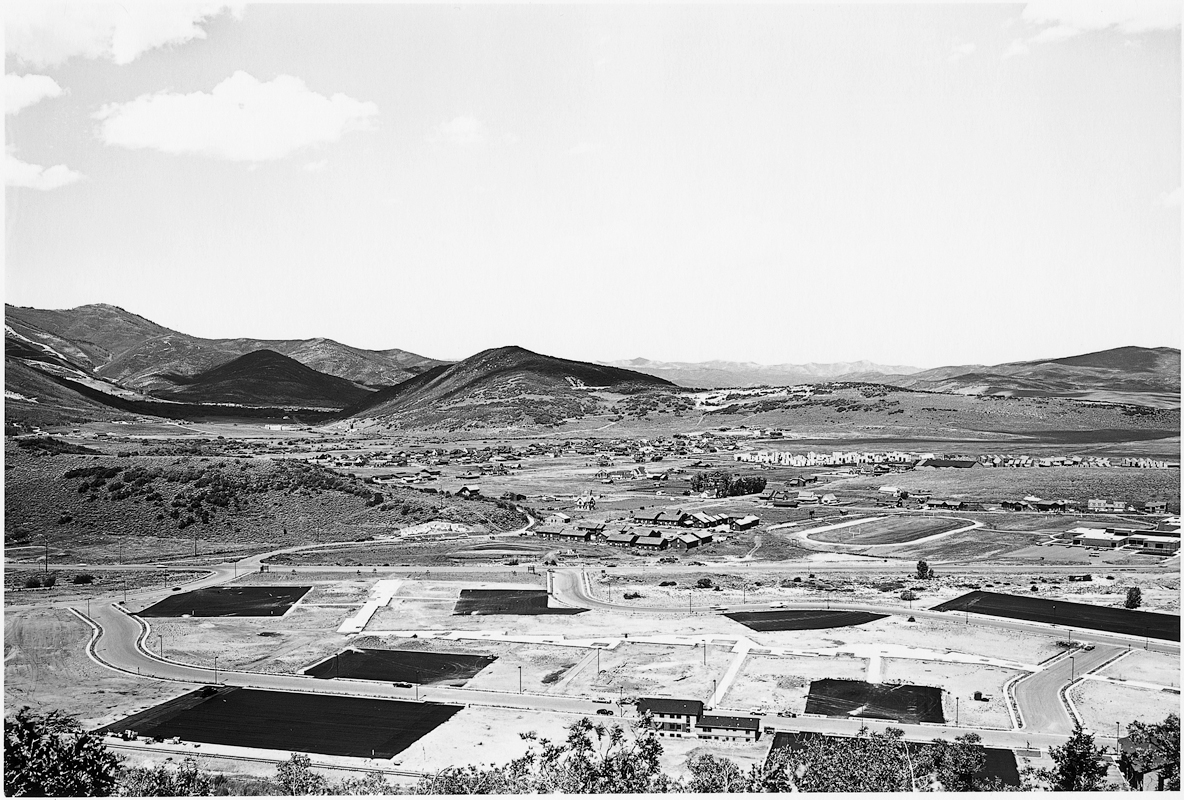

Lewis Baltz, Looking north from Masonic Hill toward Quarry Mountain. In foreground, new parking lots on land between West Sidewinder Drive and State Highway 248. In middle distance, from left: Park Meadows, subdivisions 1, 2, and 3; Holiday Ranchette Estates; Raquet Club Estates. At far distance on left, Parkwest Ski Area, 1980, #1 from Park City. Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander © Lewis Baltz

Lewis Baltz, Park City, interior, 1, 1980, #62 from Park City

Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander © Lewis Baltz

His two large projects along these lines are Park City, showing a Nevada ski resort in a stage of slipshod construction (1978-79), and Candlestick Point, the quintessential semiurban, indeterminate, trashed, American open ground near San Francisco (1988). Though his landscape is more tractable and the abuse of it by no mans as grave as Hanson’s, Baltz proves to be the more pessimistic artist. The topographical view, after all, is an attempt to map and therefore delineate earth features within a span of time and space. Topography’s depiction is a pragmatic enterprise designed to inform us of differentials on our ground surface. But Batlz’s precise close-ups —even his horizons— are dis-informing, not only because they are nondescript but because they evince no interest in distinguishing one spiritless view, or nonview, from another. Except to notice their interchangeability, Baltz is pictorially indifferent to the events that created the dishevelment that seems to obsess him in a low-grade way, just as a virus drags on in an organism.

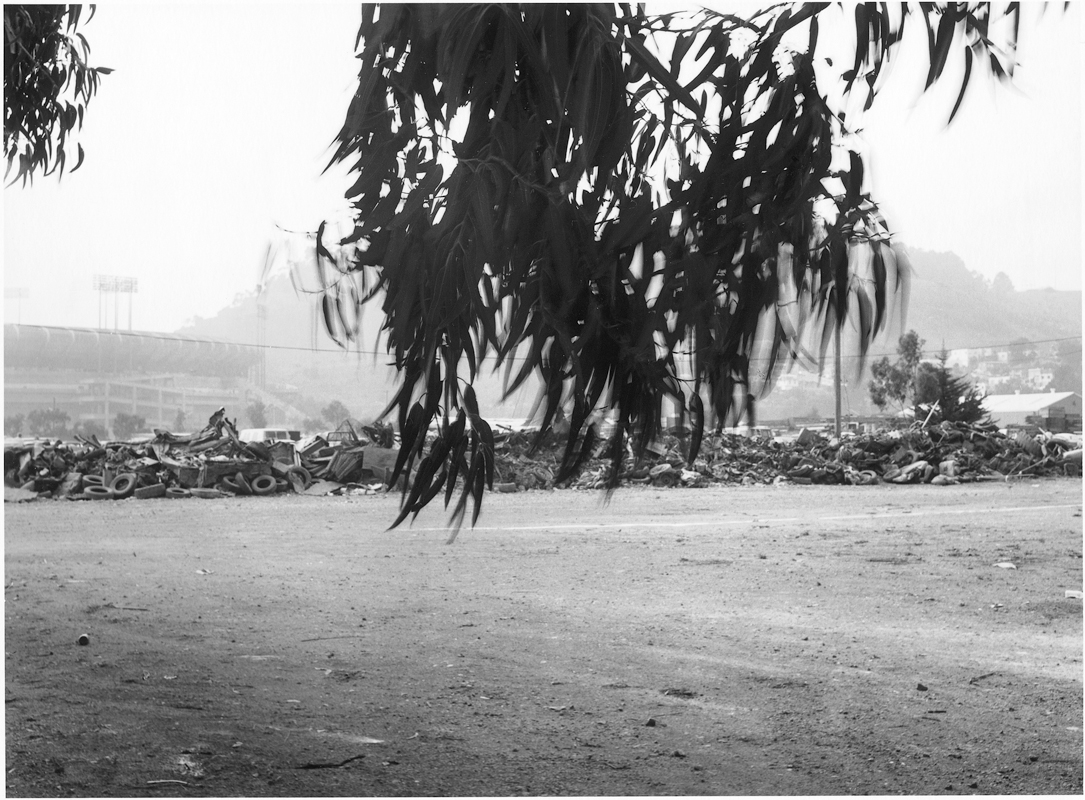

Lewis Baltz, Candlestick Point #52Candlestick Point, 1988. Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander © Lewis Baltz

Baltz makes redundancy a principle in his photographic campaigns. Tumbleweeds, crabgrass, rusted automobile parts, snap-top-beer cans, the impressions left by tracked vehicles: these proliferate in images that cover the same polemical point over and over again. His camera can never drink in enough unsightly chaff, never slake a thirst for debris and rubble. This omnivorous gaze —monotonous and impassive in its spread and reiterated in serial clusters of black-and-white photographs always printed the same size— seems entirely disproportionate to the interest of its subject. In the thirties, Farm Security Administration photographs sometimes depicted automobile graveyards in rural areas; in the sixties a whole school of photographers fancied urban bushes. Baltz’s program, mingling nature and culture, is different. It lacks elegy, and however deliberate, it is devoid of formalism, for he collects his dismal frames as if to show a world, perhaps the world, unrelieved of our forgetfulness. The sole way to drive home that prospect —of an environment consisting only of dirt— is to exclude from the visual field anything that is finished and cared for, or untouched by humans.

He leaves us to feel that this work is less worthy of being looked at than necessary to contemplate. Here are bad pictures invested with a strange psychological interest. Like ecologically minded photographers, he lets the implications sink in; unlike them, he does not suggest the value of preserving any land nor does he urge reformation of our ways. If he had any more hopefulness, he’d have to show his denatured bits as blemish or wound and therefore as still exceptional zones that can be brought back to a state that accommodates us. In short, he’d have to convey a notion of the attractive, or at least what constitutes environmental health. It is the absence of any sign attractive to us as social animals within an ordinary landscape of our own negligent making that distinguishes Baltz’s art and gives it a terrible neutrality.

Lewis Baltz, Prospector Park, Subdivision Phase I, Lot 29, looking Southeast toward Masonic Hill, 1980. From Park City. Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander © Lewis Baltz

By “terrible” I mean the feeling imparted to relatively accessible vistas of a kind of ground zero, where everything resembles a mockup. Baltz shows sharply etched and summarily fabricated presences, such as unfinished condominiums, as if they were awaiting some unspeakable test. Not enough ecological hope lies in any of this material for us to interpret it as a depiction of earthly casualty or misfortune. To the contrary, the blightedness out there (which he seems to have internalized) is a given, something that preceded the photographer and will long succeed him.

On the other hand, to viewers of politically accented landscape, attraction is a very convoluted issue. Strictly speaking whether the land seems comely or not is secondary to whether it needs to be detoxified. A conservational urgency must precede and often marginalizes an esthetic response (otherwise social priorities would be undetermined by the vagaries of taste). Still, if we do not experience some keen loss of pleasure in the wastage of the region, we are less motivated to urge measures to reclaim it. We transfer our sensitivity to injured flesh to our sense of a damaged land, provided the damage can be made evident. In these matters, the empathetic consideration is more powerful than the chemical, but less relevant to political change.

Still, merely to single out affecting landscape does not generate a very searching case for its preservation. Despite the Sierra Club’s popular use of such images, which makes us want to hold on to things, gorgeous scenes hardly illumine the real jeopardy to the environment. As for Edenic nature, whether in calendar or ad, it purveys a strong cliché content, cloying rather than seductive. Far from apprising us of the dilemma of pollution, the tourist or consumer propaganda that utilizes such images tends to exploit and worsen it. Landscape photographers who want to make a statement about the deadening of the environment find that their own medium puts them into a quandary. They must steel themselves against ingratiation while somehow affirming the value of their abused subject.

Robert Adams, On Top of the La Loma Hills, Colton, California, 1983. From the portfolio Los Angeles Spring © Robert Adams, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In strictly documentary imagery, this quandary is beside the point. The act of bearing witness justifies itself quite simply as it points out such evidence as the oil-smeared wings of an egret or the balding effects of acid rain in the Black Forest. We need such witness as a palpable indictment of accident or malpractice. Nevertheless, as soon as it localizes examples of wrongness, documentary is exhausted of further meaning. It does not satisfy those who, in addition, to their search for a record, look for the sounding of an attitude.

In contrast, there is a kind of picture that alerts us to the ways we ourselves remember, reflect upon, and forecast our changing situation. No matter how often we hear of media documentary as an editorial, even as propaganda, we perceive it as a disembodied product, without any investment of the photographer’s individual consciousness. Of course the image doesn’t need that consciousness to make an impact upon viewers, as might the impersonal depiction of a crime that seems to implicate us all. The sight of it may or may not spur us to action, but it does not raise in us any awareness of how we ourselves process evidence. All photographs mediate reality, but instead of displaying a corporate perspective or ideological dogma external to our beings, some of them —the ones considered here— extend to us an individual regard similar to our own.

When the subject is nature, the regard tends to be solitary. Landscape seems to call upon us to be intimate with ourselves, as if to awaken in us pleasures, memories, or hopes that are not yet acculturated. The meaning of landscape is arguably bound up with an appeal to the illusion that within each of us lies something unshareable and not yet socialized. This is partly because of the ineffability of ungrasped sensations perceived in the far reaches of land under open air and partly because it still pleases North Americans to fantasize about nature not as culture and therefore not as a communal experience. Of course we know very well that the reserve into which we place our ideas of nature is a cultural reserve. But perhaps alone among the developed nations, we can still imagine our actual contact with nature to extend past that reserve, as if there were a frontier we hadn’t yet transgressed. One photographer who knowingly works within that conflict between the imagined and the transgressed is Robert Adams.

Robert Adams, Expressway. Near Colton, California, 1982. From the portfolio Los Angeles Spring © Robert Adams, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Off the freeway near Colton, California, Adams climbed an eroded hillock. Fumes, haze, and effluents halate the otherwise graphically silhouetted black-and-white tones of photographs such as this and others he made for his book Los Angeles Spring. While the effects are redundant,the compositions are individually realized, each of them variants in an expanding poetic search. What Adams achieves is a poetry of depredation. In an era of landscape color, the black and white strikes a memorial note, and a curious mournfulness pervades scenes of an otherwise humdrum brutality. It’s not that Adams appears to think tenderly of these undeserving views, but that in capturing them as moments of lonely experience he projects them back into a nineteenth-century landscape tradition and perceives their horizons as seemingly deserted now as they were then. A weariness of view fuses with the freshness of radiant seeing, as if Robert Frank’s vision of a fifties America had blended with the imagery of Carleton Waktins’s post-Civil War Yosemite. Adams shows withered eucalyptus trees, abandoned orange groves, and bulldozed, broken stretches of earth. Having earned his attention, they stay in mind as naturalized forms, lost to a process symbolized by the road or developers’ trails.

In the introduction to The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Photography, Adams writes, “Physically much of the land [the West] is almost as empty as it was when Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan photographed there, but the beauty of the space—the sense that everything in it is alive and valuable—is gone.” Adams considers the nineteenth-century photographers privileged because the clean skies they saw could illustrate the “opening verses of Genesis about light’s part in giving form to the void.” Their cameras could take their fill of scenes that are now obscured or faded out by an amorphous whiteness against which the reminiscent photographer now has to struggle to describe depth.

In Los Angeles Spring, that description and the conventionally nostalgic desire that went with it is foiled, leaving us to judge only unkempt things in the foreground. Deep space is equated with a past we cannot restore. Consequently, these recent images evoke a regret about the wealth of information streamed out in the light. They are comparative pictures. They imaginatively comprehend a span of events in which affection for nature must be misplaced if it is to have any object at all.

On the other hand, it is possible to reposition one’s attitude and get enthusiastic over a new though sinister beauty. The ambiguous shallow space of Adams’s southern California becomes very declarative in John Pfahl’s Smoke series, begun in 1988. By using a telephoto lens, Pfahl flattens the billowing, polychromed emissions from factory smokestacks. The subjects are tightly framed and very definitely brought within optical range, but at the cost of disturbing the viewer’s intuitively physical relationship to their space. The telephoto’s seeming intimacy is undermined by its neutralizing vantage; we can neither establish the locale nor gauge the actual depth of the sighting. Quite aside from being the only way Pfahl could have depicted such a noxious phenomenon without choking, he clearly uses his telephoto lens to invite us, suspend us in some unmoored place, and then disquiet us, over and over, by a study of atmosphere ecstatically befouled. During his long career, he has kept us aware of the surface of the image at the expense of its illusive depth (by disposing lines within the scene that read as two-dimensional geometric figures on the picture plane), and he has refused to ground the viewer’s perspective by any kind of introductory ledge. Everything that appears in his work is perceived as if from an indefinite mental space of our own. Yet, in the end, the spectacle of the roseate benzene cloud, visualized in the melted colors of a kind of pastoral sublime, overwhelms our understanding of its evil. This work is too deliberately ingratiating to be critical, even if a crucial comment —a record of dirty clouds— defines its reason for being.

John Pfahl, Bethlehem # 16, Lackawanna, N.Y. From the series Smoke, 1988-1989. © 2002 George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

Perhaps the flaw in such a project as the Smoke series is its need to avoid a condemnation of the obvious. Despite having been enveloped once in benzene vapor, all the photographer has to say—all his irony will allow him to say—about such misamas is that they’re beautiful. We, the victims of such stupendous pollution, are reduced to applauding his artfulness in depicting it! Further, these clouds momentarily take heroic shapes; they belong to a stereotypical genre that celebrates the productivity of factories. Who could be blamed for imagining that Pfahl approved of it? At this particular historical moment, the Smoke series could only be conceived in the United States, when, the general standard of living just beginning to show signs of decline, ecological consciousness is afoot yet significant environmental measures are defeated. Pfahl’s blend of luxuriant estheticism and alienated space has never proved so hollow as when it handles real debasement of the environment.

Yet it was never easy to visualize that danger. Photographers have had an aerial/abstract go at it; they have also adopted an affectless nihilism toward it. Some of them have waxed nostalgic or have been perversely engaging about our common peril. We grant them their expressive resonance. Just the same, at each turn they depended too much on their viewers to contribute their own moral earnestness to the scenography. The diffuse appearances of the terrain —whatever the state in which they were found— do not of themselves strike us with any urgency. We have been schooled to contemplate a pictured landscape far more than to protest loudly in common cause to rescue the screwed up territory it may show. We feel that landscape is “there” for us, and if for any reason we are given country that puts us off, we turn elsewhere. Arcadia, even a sad Arcadia, was inviting. But how are we to be aroused by a spectacle we reject: an American wilderness we ourselves have done in?

That kind of panorama in the West has been addressed by Richard Misrach with increasing vividness throughout the 1980s. To begin, he offers a totally convincing sense of place—the Mohave, the California inlands, the Nevada deserts, over which he has roamed repeatedly. His moment of perception is always the present, gritted in by sandy ochres and limned by sage green, mauve, and blond hues often merging into an exquisite bleached depth, though sometimes reddened by dusk or fires. Misrach lives such moments to their sensory brim without standing on any ceremony. He gives us the feeling that what happens out there in the nominal wild happens for him and to him quite in advance of being filtered through any memory of art.

Other photographers have just as keenly possessed the land through their pictures, disclosing refuges we thought were scarce. There is something enterprising, even sporting, and yet a little sad about their project, for they bring back appetizing views as if they were trophies. Misrach works the flip side of this mode: he camps out in what passes for the remote desert only to show our unexpected hand in it everywhere. He’s a specialist in transmitting drab, and finally bad, news from epic landscapes.

Joe Deal, Backyard, Diamond Bar, California, from the Los Angeles Documentary Project, 1980. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In 1983, as twilight gathered at Lake Havasu City, Arizona, Misrach evoked the distant twin arches of McDonald’s as a precious beacon in the desert. This was a sensuous epilogue to work done in the 1970s by a group of photographers that included Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal, and Frank Gohlke, who showed the West as a Pop landscape in an important exhibition called “the New Topographics.” Their theme, suburban development as an unexpected vernacular, disgruntled a number of viewers who were put off by the work’s cool, noncommittal style. Actually, matters would not have been improved had the photographers been judgmental, for it was their very choice of such material that provoked. How eye-worthy were the ranch-style houses at the end of a new road, with their lonely tree sprigs, or the mobile-home parks and RV camps, satellite towns at some dry outskirt? Here art reckoned with the decentering caused by a shift in population to the Sunbelt. Arrangements for those middle-class folk who were passing through or who had retired had a provisional look about them —and that look was captured by the New Topographics. But the photographers concentrated so much on an atrophy of community that they didn’t deal with its consequences to the land. Now, in every case their work has darkened in mood as it has explored that land. In Misrach’s book Desert Cantos, that mood has come to flower.

Richard Misrach, Submerged Lamppost, Salton Sea, 1985

© Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

From the first, one gleans Misrach’s intense interest in the desert as, of all things a social phenomenon. His romanticism may have initially brought him there, but his realism takes over at the actual site. He writes, “One only needs to stand outside a 7-11 at Indio with a cherry slurpy, or dangle one’s legs in a Palm Springs pool in the 105-degree early morning sun to know what is desert.” As the title Desert Cantos suggests, however, he transmits his realism back into a poetic framework that has Dante-esque overtones. Each of the cantos, his photographic chapters, develops a topic: The Highway, The Inhabitants, Survival, The Event, The Flood, and so on. Drawn in by the rocky forms and velvety tones, our normal attachments to things as they are near and distant tend to be reversed. Tiny remnants left by passersby or abandoned works are scattered everywhere and nowhere within awesome perspectives. The boxcars of a long Santa Fe freight train are reduced to lapidary points of scarlet and gray way off in a plain of live scrub. In one canto, The Event, the same endless horizon suddenly takes on a narrative interest, for it tells of the arrival of the space shuttle at Edwards Air Force Base and of the people, colored silhouettes on a blinding flat, who are awaiting it. The Future —a dot in the sky— is about to descend into this immemorial place. Or is it the Second Coming these cowhands, army personnel, and sightseers are about to witness? Biblical parallels are certainly a part of Misrach’s overview of his desert campaign. His notion of The Flood is filled out by the Salton Sea, an utterly still body of water that has inundated telephone poles and swamped a gas station and a kiddy slide. Such limpid scenes have an eerie, unforced beauty that whispers to us of retribution. And he concludes with the Fires, vegetation burnoffs, often uncontrolled in their sweep, which he photographed at such close range as to almost make us feel their scorch.

Richard Misrach, Desert Fire #249, 1985

© Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

For all their ominousness, however, these crackling vistas are not yet infernal, as are a later group Misrach calls The Pit, and his latest book, the even quieter Bravo 20: The Bombing of the American West. The Pit acts as a dirge to thousands of livestock that died of unexplained or unexamined causes and were thrown into remote Nevada dumps. Their hooves and hinds protrude from the silt like so much refuse. The burnoffs provided a startling new subject for Misrach’s photography; his dead animal pictures amount to a scathing political exposure.

Richard Misrach, Dead Animals #327, 1987

© Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

Yet both subjects are treated with a caressive regard that is eloquently incongruous. A tension is set up between the magnitude of the description, the physical presence of large prints, and the dread of their subjects —disgorged, as it seems into our own space, from which we are not meant to escape. Hitherto, his attitude toward the desert was one of almost anthropological curiosity, and we were cast as wayfarers there with our guide, who saw with real opulence. Presently, he maintains his vision and takes us into a holocaust.

Misrach was not the first to discover the devastation wrought at Bravo 20, the United States Navy’s bombing range in Nevada, nor the first to learn that it had all been illegal for more than twenty years. The worst kinds of violence had been committed there, to the deafening accompaniment of supersonic jets. He happened upon the place in his travels, joined the activists who had come in to resist the military, and made his reflective pictures of the scenery. They show a cratered landscape, barren of all but the most stubborn plant life, yet littered with thousands of bombs and shells. These photographs inadvertently recall Roger Fenton’s pictures over 140 years ago of the Crimean battlefields, strewn with cannonballs that resemble the feces of some obscene metal bird. But Bravo 20’s ready-made quality as a moralized landscape lies in the fact that it is not a battlefield but a practice zone. Misrach has no trouble in revealing how a macho culture has literally vomited all over the very same environment that in yesteryear it had held up as the territory of its heroic aggressions. Because they show the results of the United States military purposefully at work rather than just one of its accidental by-products. Bravo 20’s wastes are even more demonstrative than those pitiable animals brought down by chemical or radioactive taint.

The economy of the tacky developments out in the western drylands —the dreck —is deeply entwined with our militarism. The people of Fallon, Nevada, though terrorized by the noise, were loath to protest the armed forces’ usurpation of their nearby ground because it brought revenue into their town. It seems as if we have extreme difficulty either in adapting ourselves to nature or protecting it from us. In speculating along these lines, Misrach has never argued for anything so radical as removing people from the land. But he has proposed that Bravo 20 be turned into a national park as the country’s first environmental memorial. Sightseeing routes within it would be called “Devastation Drive” and “Boardwalk of the Bombs”— apt names for a horizon that deserves to be considered prodigiously wrong.

Max Kozloff

This essay was published for the first time in “Lone Visions, Crowded Frames: Essays on Photography” by Max Kozloff, The University of New Mexico Press, 319 pages, 1997.