Sommaire

— Jean-François Chevrier: “Territorial intimacy. Territory and assemblage”

— Antonios Loupassis: “Photographs”

— Patrick Bouchain : “For the construction site as a place of experiment”

— Marina Ballo Charmet : “The Terrain, Frontiers and Margins of the Gaze”

— Wiktor Gutt : “Does freedom lead to solitude, or does solitude lead to freedom?”

Saturday 7th December, in the auditorium of Jeu de Paume. From left to right : Marina Ballo Charmet, Antonios Loupassis, Jean-François Chevrier, Patrick Bouchain and Wiktor Gutt.

“Territorial intimacy.

Territory and assemblage”, by Jean-François Chevrier

This study day explores some ideas whose basic hypotheses I set out last May. It is also related to – but not dependent on – a course I have been giving at the École des Beaux-arts since October 2012, about the history of primitivisms. “Territorial intimacy” refers to a kind of experience that has been documented and can in some circumstances be revealed by photography. This experience comprises the exchange that takes place between human beings in a given or constituted environment. It appears in a variety of literary and visual documents and is produced in varying contexts: the arts (in the plural), sociology, anthropology, etc. Intimacy defines the experience of the territory as a milieu, experienced in a more or less durable way by an individual or group.

I think it is important to note that the idea of the territory implies duration, whereas intimacy can be a brief, transient experience. To link intimacy with the territory enables us to think about biographical forms, modes of subjectivity and subjectification, in relation to geographical data, which are themselves conditioned by historical processes. The notion of territorial intimacy condenses two heterogeneous heuristic parameters: intimacy, which is psychological or psycho-physiological, and the territory, which is geographical. We thus go from biography to history via geography.

Last May I also indicated an ethological model. This model features recurrently in the speculative forms of territorial intimacy produced by literature and modern art. The ethological model of the territory encourages a conception of the habitat centring on the image of the body, as understood since Paul Schilder’s seminal book. Here we need only think of the ideal of the spider secreting its web. But the spider’s strategy is still a rather remote and perilous example for a human being. Human habitat does not derive directly from instinctual equipment, nor from a stable schema of relations to the biotope.

The notion of territorial intimacy presents one major difficulty: there is a risk that it will encourage a lax and nostalgic approach to native identity, by idealising a state of “primitive” symbiosis. It is a fact that, in a world governed by discriminatory norms of cultural belonging, territorial intimacy is often engendered in response to a situation of exclusion or social marginality. It is a form of compensation. When we think of domestic forms of intimacy we usually think of the intimisme of the bourgeois private sphere. Territorial intimacy tends to subvert the institutional distribution of the private and the public. But this subversion is often only a compensation provided out of necessity and urgency for the difficulty or impossibility of access to the official public space.

Images of territorial intimacy, a few examples of which I showed last May [Territorial Intimacy and Public Space 1/3], can be related to a pictorial tradition which emphasises the inscription of the body in landscape. The “landscape with figure” formula allows of countless variations. The visual interaction between a figure, whether static or active, and an environment, itself defined as a (static) setting, or as an enveloping, active milieu, is an effective schema. But it does not allow us to question the very conditions of territorial intimacy, that is to say, literally, what conditions it. That is why anthropologists, for example, when not blind, have good reason to be wary of the photographic image, and to prefer verbal description.

The question is, how can documents of territorial intimacy, when this is lived within the limits of exclusion or social marginality, contribute to a redefinition, or even a reinvention, of public space. At the very least, this presupposes that the conditions of experience should not be obscured by an effect of excessive idealisation or negative aestheticisation (the trash tendency). It also presupposes that a general meaning can be deduced from specific documents, without this being a mere thematisation.

I should make it clear that I understand “public space” here in the sense of a realm of expression and exchange theoretically enjoyed by actors in civil society, at least under political regimes that guarantee freedom of expression. This sense of the term corresponds to the German term Öffentlichkeit, which has gained currency since Jürgen Habermas’s description of the formation of variant forms of bourgeois public space in the early 1960s. Public space designates the domain of opinion, expressed with varying degrees of rational argument by speaking subjects who are also subjects under the law.

Access to public space is the condition for exercising a democratic sovereignty that consists in more than just electing representatives of the people. In this sense, the term designates an abstract sphere of interlocution, given concrete form by various supports or media. Today, the Internet is the main sphere for the constitution of an “englobing” if not global public space. Because of its virtual reality, the Internet transcends national frontiers and institutional specificities. But, as Habermas has shown, a space of private dwelling, such as the drawing room of a bourgeois home, can also be the place and support of public space. Under certain political circumstances, when the state controls and monopolises the field of expression of opinions, private space can become the refuge of public space.

Even if it can take form in specific locations, public space, in this sense, does not necessarily imply a material conception of space. But it is clear – and we will see this confirmed today in a number of different ways – that someone who wants to work to protect and extend public space must take into account its spatial, local inscription. The question, practically, is that of forms of relation between private and public, that is: how do we put in place and represent this relation without reducing it to fixed, sterile and discriminatory norms? This is where territorial intimacy proves valuable. For it highlights the not only spatial but also local character of sharing public space.

The local inscription of the private/public relation is not the secondary effect of a juridical definition or of a pre-defined idea or ideal. This inscription must remain open to experiment, so that the sharing or distribution of public space can, as far as possible, provide an opportunity to overcome social and cultural discrimination. These notions of separation, distribution and sharing are all more clearly contained in the French word partage, and its ambiguity neatly sums up the difficulty here. Furthermore, before getting on to any kind of programmatic discussion, it must be admitted that public space, in its material form, is very fragile, as fragile as the possibility of democratic expression. It is constantly exposed to domination by private interests. In the urban environment, as in the media, it is disintegrating, crumbling, losing all substance, as a result of an urban design driven by a mediocre, demagogic conception of conviviality.

In addition, as I briefly mentioned back in May – and I hope we are able to be more precise today – the forms given to the experience of territorial intimacy are themselves fragile. The current taste for auteur photography favours neo-picturesque forms and effects of style. Today we are going to see some more demanding forms, drawn from specific experience, often barely picked up by the radar of the media and artistic institutions.

***

As I have already pointed out, this seminar is linked to the enquiry into primitivisms, folklore and the vernacular that I have been leading at the École des Beaux-arts since October 2012. I would simply like to sum up the two observations arising from this course that strike me as the most useful for our meeting today. The first observation concerns the book of images published by Pierre Clastres in Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians. I drew attention to these images in May. We studied them very closely at the Beaux-Arts and we noticed that the sequence of images does not follow the text, but that it recaptures the dramatic nodes of the ethnographic analysis produced in the text. Here I shall limit myself to two or three indications.

On the first page are two images that condense the idea of territorial intimacy: the view of a forest camp, and, by an effect of juxtaposition, the face of a person known as “Old Paivagi” sitting on the ground, in a shelter, his face towards the photographer. This man was Clastres’ main informant. After that, the following spread introduces two other figures, Chachubutawachugi and Krembegi, who both occupied marginal positions in the Guayaki community. In the text, Clastres describes the distribution of male and female roles, between the men who hunt and women who deal with domestic chores: this delimitation is symbolised by the bow and basket. Krembegi has renounced the bow because he is homosexual. This gap is expressed in his position, kneeling in the middle of empty ground. But Chachubutawachugi is the unlucky hunter, who has involuntarily gone over to the side of the women: he is lying in front of a basket. The next two images heighten the uncertainty of the symbolic distinction, for they illustrate the gathering activity carried out by men: the collection of larva on the left and Chachubutawachugi leaving to gather honey.

The four double pages after that illustrate the process of initiation which enables boys to attain the status of hunter, from the “construction of the shelter use for male initiation” to the portrait of the child with a small bow. But the initiation unfolds in two phases: the real culmination of the process is illustrated further on, on a double page where we see the portrait of a young initiate in profile. The profile view allows us to clearly see the lip pierced by a long stick, or labret, which shows that the man has achieved a certain rank among the hunters and can have access to women. The image on the right shows “bow fishing.” The bow is an instrument, a weapon. It is also, and perhaps primarily, a tautened curved form. Its tension is communicated to the body of the archer, who is seen here straining before he releases the arrow. The body forms a counter-curve. The taut curve of the bow forms a composition with the string marking the verticality of the body.

This image leads me to a second observation, concerning the primitivist imagination. The hunter/bow-fisherman is a figure of the naked man, the all-naked man. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, total nudity has been associated with the idea of the outdoors. The naked body is completely exposed to the air. The “all” of “all-naked” corresponds to the “open” (or full) of plein-air. On both sides, there is an attempt at completeness. Writing in L’Art décoratif d’aujourd’hui in 1925, Le Corbusier affirmed: “The all-naked man does not wear an embroidered waistcoat; he wishes to think.” This idea of a mental disposition freed of all superfluous decorum links primitivism to what Mallarmé identified in Manet as “the question of the plein-air.” For this “open air” was not exactly the same thing as pleinarisme, no more than the idea of complete nudity can be reduced to naturism. The question of the plein-air remains to be answered.

Already, for Mallarmé, it meant locating the domain of pictorial representation outside any kind of institutional repertoire. It was vain to try to increase the archive of painted or spoken things. “Nature exists,” said Mallarmé, “She will not be changed, although we may add cities, railroads, or other inventions to our material world.” And he added: “The sole available action, forever, is to grasp the relations between times, rare or multiple; following some inner state, and if we wish at will to extend or simplify the world.”

Since Mallarmé and Le Corbusier, the clutter of superfluous artistic objects has increased dramatically. But Mallarmé’s proposal, and Le Corbusier’s call for thought freed of the overlay of decorum, have value beyond the necessary postulation of mental hygiene and ecological restraint. The “available action” is located on the side of relations that can be established “following some inner state.” Territorial intimacy is one of these states, because it brings into play a psychological and geographical experience within a geographical environment. That said, the experience still needs to remain open and not withdraw into a rigidified primitivist imaginary.

“Photographs”, by Antonios Loupassis

Introduction by Jean-François Chevrier

We are now going to look at two sets of images made by Antonios Loupassis in Paris in 1996–97 and, very recently, in 2013, in Imphy, a small town in Nièvre (Burgundy). Antonios was trained and practised as an architect in his home country, Greece, which he left in 1993. The first set of images goes back to the time when he was selling the newspaper La Rue and he met Marc Pataut, who gave him a camera. The second set is a piece of reportage on Imphy, the small town where he has been living for several years now. We are going to see a significant selection from these two ensembles. Antonios will say what he has to say about the images, and then answer any questions you may have.

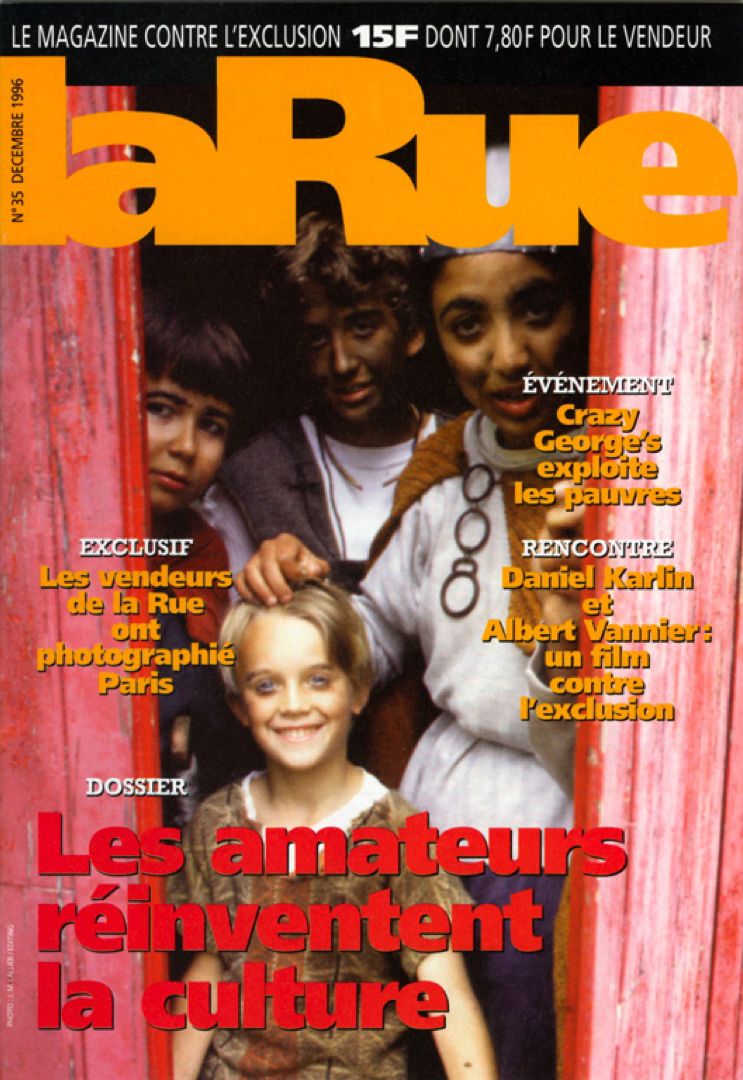

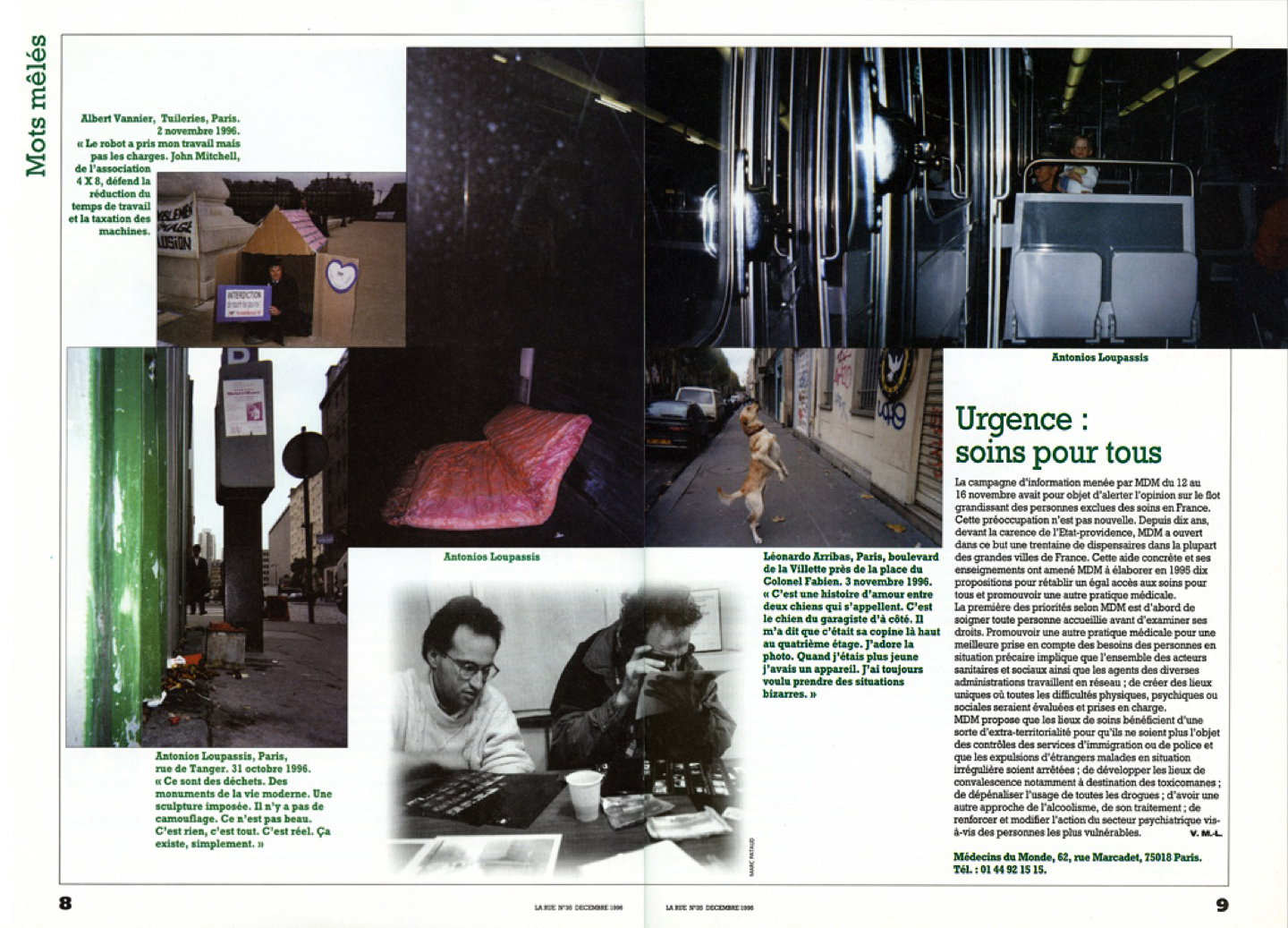

The photographs presented here are taken from sets of images made by Antonios Loupassis. Trained as an architect, he left his home country, Greece, in 1993. The first set of images dates from 1996–97, which is when he was selling the newspaper La Rue, published on behalf of the homeless, in Paris. That was when he met Marc Pataut, who gave him a disposable camera, as he did other vendors of the newspaper. Some of these photos were published in issue no. 35 of La Rue in December 1996. The second set is a piece of reportage done in 2012–13, this time using a digital camera, in Imphy, a small town in Nièvre [Burgundy], where Loupassis has been living for the last few years.

The Street (Paris, 1996–97)

The context, by Marc Pataut

At the time, we at the association Ne pas plier wanted to enrich and diversify the photographic archives of Médecins du monde concerning the homeless. Their iconography on this subject was rather poor, because usually press photographers only give humanitarian associations their surplus images. We therefore persuaded them of the interest of doing their own photographic work with the homeless, in collaboration with La Rue. This newspaper was sold by homeless men and women in the streets and in the Paris underground, and what was remarkable is that it really tried to integrate the sellers: they had a pay sheet, were given medical and social assistance, etc. At first, we wanted to deal with the difficulty homeless people had getting treatment, but we soon realised that the problems this raised were too complex. It is very complicated to photograph one’s own milieu, whether in the street or in a foyer: things soon get conflictual. We therefore suggested that the vendors of La Rue photograph their own use of the street and the city. I gave about ten of them disposable cameras. One was Antonios Loupassis, and he produced the most images.

Double page 8-9: photographs by Antonios Loupassis,(4) Albert Vannier (1) and Leonardo Arribas (1). At the bottom, a black-and-white photograph by Marc Pataut on which, to the right, we see Antonios looking at contact sheets. Today, he uses a digital camera, but in the days of La Rue Marc Pataut had given the vendors disposable cameras.

His photographs were pretty extraordinary. What really interested me was of course Antonio’s personality and his vision of the city, but also, quite simply, the documentary aspect of his images, which show us another use of the city, a practice that may not be ours, a practice of a city that we know but that we do not look at in the same way. This project gave rise to a touring exhibition in Paris. I remained friends with Antonio afterwards and he made his own contribution to Jean-François Chevrier’s seminar.

The Images, by Antonios Loupassis

I think that images should be allowed to speak for themselves, like a language. I’m not a very good talker. I prefer telegrams, or photographs. It’s such a dense language, much more complete, with unlimited possibilities.

In some of my photos I photographed the reflection of my camera lens. It’s a symbol which represents the eye, which replaces the symbol of the eye in the imaginary of Ancient Egypt. Today, the lens does the work in place of our eye, as if that was how humankind had evolved, and it’s almost a new archetype, because camera lenses are everywhere. Every day, all the time, our eye records things, but with a camera it’s fast, it’s extraordinary, it’s the speed of light. We say in philosophy that if you can pose a question, that is because the answer was already there and that we hadn’t seen it. That aspect is always there in my photographic work. Generally speaking, I do a lot of work on reflections, on any kind of surface, because a reflection is the relation between what we cannot touch and the real.

The image expresses the relations between forms, it talks about the relation between forms and the person looking at them, who may be an architect, a very naïve person or an intellectual. Literature is not my passion – this is something I decided when I was a teenager. To express myself I found the path of oral expression, then images and forms: it’s a much more comprehensive language, it has no need of commentaries. There is geometry, lines, a conception of symbolism.

Antonios Loupassis, La Rue, Paris (1996–1997)

1996–1997 was a much more innocent period than the present one. The atmosphere in Paris was different: less vulgarity less aggression, people were much nicer, you could talk without running the risk of getting beaten up, as you do today…

What I wanted to say at that time was not so easy. I wanted to keep my personality secret, I wanted to keep what was mine. Instead of an answer, I had the image, a medium that I got the hang of very early on, like a weapon to protect myself with – or at least express myself – with regard to my own self, in the first instance, and then from others, from the outside world. It’s a form of visual expression coming after years and years of very powerful experiences.

That was when I had the good fortune to meet Monsieur Pataut and I want to say here how much I learnt from him. He was an extremely important and respected influence for me. I think that no one has ever managed to touch on humanity, on people, the way Monsieur Pataut does. It makes me aware of how hard I find it to understand people, human beings. We talk about humanitarianism, humanism, but we’re hardly capable of saying hello to our neighbour. These are simple things, but they have to be addressed.

The architect works with objects that are not living existences. He can build an atmosphere, an ecotope, an ecosystem, defined within the framework of modern ecology, in the sense of geometry, the exact sciences, the human sciences. There is a multitude of aspects to be studied in terms of the architect, but the human being itself is a temple. Monsieur Pataut has managed to touch on it, and he is still helping me to understand how he was able to do it. Of course, when you’re an architect, when you’ve organised a project, imagined all kinds of things, there is always this question: “Who is the person that is going to live in there?” It’s a classic question, but if we express it, it’s for everybody, because it’s not easy to understand what an architect does. When it comes to photography, the questions we raise are expressed in a much more abstract, more immaterial way.

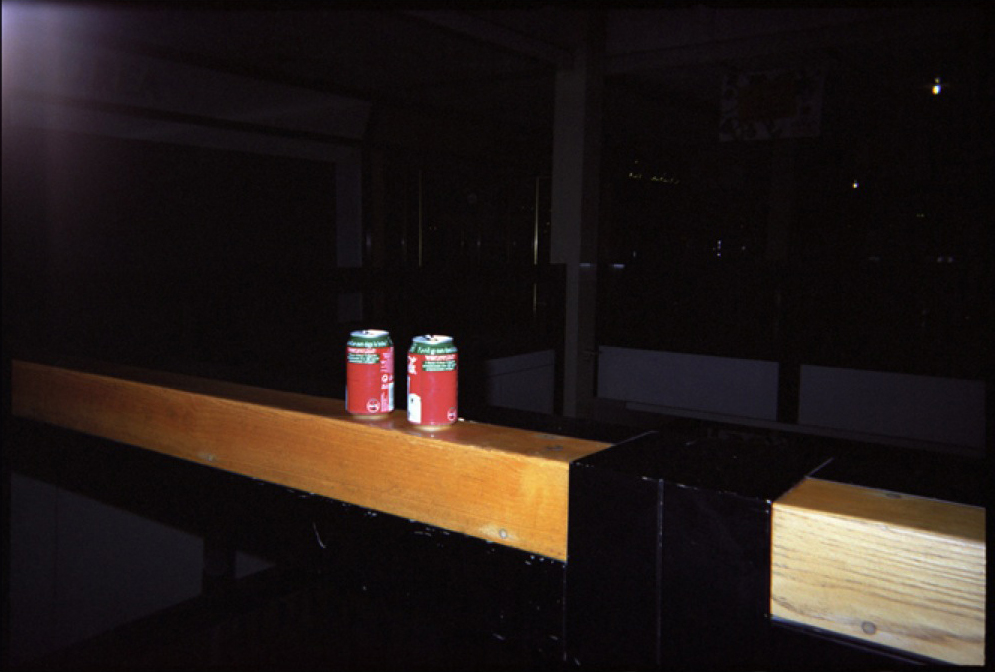

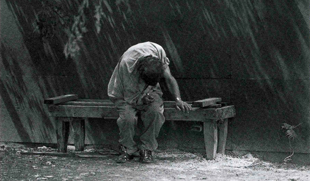

I photographed things in Paris that really caught my eye, especially at night. Every day Monsieur Pataut supplied me with two or three disposable cameras with about thirty shots. The fact that they were disposable, with a plastic lens, intrigued me. I thought to myself: the throwaway spirit, the ready-to-junk, is something that preys on us all the time these days. It’s something that can happen to anyone. So this throwaway thing has to be transformed into an aesthetic tool. I was also influenced by my experience of cinema. There was a time when I used to watch two films a day – Bergman, Coppola, all that. Nowadays digital is degrading the quality of films and we are moving further and further away from simplicity. That is a mistake. The things that caught my eye were the “everyday currency” of the street. Images speak for themselves. There is always the beauty of things, if only the way people manage to survive over the years. In some of the photos I photographed parts of my body. This was in response to questions about the classical aesthetic, and about myself. One day I saw a tramp sleeping at Austerlitz station, lying on a bench. It was cold. I thought, “This really is a scene out of Leonardo da Vinci.” And I started asking questions about myself. There are moments of innocence, there are moments of confession, psychoanalytic moments. Maybe I’ve got into confession that is too personal, but I have to talk about what happened to me.

Jean-François Chevrier (left) and Antonios Loupassis, Saturday 7 December 2013. Auditorium of the Jeu de Paume. Photo Adrien Chevrot © Jeu de Paume.

Imphy (2012–2013), by Antonios Loupassis

At Imphy I took several thousand photos. It was quite an experience. I think most French people don’t really know the French countryside. They spend a few weeks there on holiday, once a year, and there are things they will never understand.

The specificity of Imphy, a town in the middle of Burgundy, is that they mined iron ore here. Iron is extraordinarily abundant in Burgundy. It has shaped minds and landscapes for several centuries. In neighbouring towns such as Corbigny and Guérigny there are tons of silica. It’s a kind of black glass paste, very beautiful, which is part of the process of purifying the mineral. Nowadays they use it for roads. It’s very tough.

Imphy is the industrial revolution. I have never seen it before the way I have here. I have lived in the Paris area, where there were old factories, but they’ve started to disappear. Here, the industrial revolution is still around. Imphy has one of the most modern steelworks of the whole ArcelorMittal group, with a blast furnace that never stops turning out steel and belching smoke – you can’t stop a blast furnace, it would take too much energy to get it going again, because the iron cools. Down there they make parts for Dassault planes and Ariane rockets. It took me at least three or four months to become aware of this history.

A long straight road runs through the town from Nevers. The town developed axially, to the left and right of this main road. All around that you have the factory area, the outbuildings of the ArcelorMittal steelworks. It’s almost a monument, like the Pompidou Centre, with extraordinary shapes. Some of the buildings date from the 19th century. There is also a church that goes back to the period as the basilica of Saint-Denis, but architecturally it’s nothing special.

The photos of Imphy were taken with a digital camera. It’s much easier than a camera that uses film but the quality of the image is not the same.

You move a bit and the eye is pleased, you feel happy with what you see. It’s a composition, like in music. Even when I choose things that are less pleasant it’s a composition too. It’s a style, if sometimes an anti-aesthetic one. Anyone can understand the difference between a Consolation by Chopin and a work by Xenakis. It’s not the same taste, the same dish, but in both cases there’s a brain behind it doing the composing. I wasn’t trying to make pretty postcards here. There is a postcard mentality, but back to front. In Greece, tourism is a magnificent industry that brings in money, and the glamour of the postcard speaks to everyone, as a way of showing an extraordinary country, a paradise. Personally, I tried to make backwards postcards: a negative aesthetic. It’s neorealism, a kind of minimalism.

In my photographs I put the emphasis on passing time, slipping away between each moment and between each photograph.

“For the construction site as a place of experiment”, by Patrick Bouchain

Speaking to Annie Zimmermann, Urbanisme no. 338, Sept-Oct. 2004.

The construction site is a place of questioning and progress. To build is undeniably a positive act, for many reasons. Among other things, the construction site gives a lot of people work, and it is a place where everyone is able and wants to show what they can do as part of a team. The construction site has always been a key forum of exchange, with the vital need for shelter expressed in the first constructions later being enriched by the pleasure of architecture. To satisfy these human aspirations today, we still need to get building, to undertake work so as to better people’s lot, even if the operational structures have become more complex.

Naturally, local government views the implementation phase with a degree of apprehension. Before the decision is made to build, they go through the planned operation with a tooth comb: is the project in the general interest? Is the budget financially bearable for the municipality? Is it technically feasible? Etc. These rather wearisome study phases are followed by the exciting moment of choosing the architecture and the builder. The building will be unique – no one ever builds two identical edifices – and therefore experimental in itself. It is an adventure, a time of discovery, and therefore requires real performances on all sides. Which is why the construction site should be seen for the noble thing it is. How can one despise artisanal work? We have forgotten that everything around us, both our internal and external environments, was made manually – by men. And it is precisely on the construction site that all these skills come together, those of the workmen, of the engineers, the architects, etc. – an infinite richness. It is a shame not to make the most of all these accomplishments. The construction site should be a space for training. It should be possible for anyone interested to come and observe the evolution of the work, and obligatory for anyone studying – or specialising in – construction, since knowledge is acquired by experiencing and imitating.

Let us consider something that costs nothing: every work site should be an opportunity to share public knowledge. Schools – engineering, architecture, building schools, etc. – should have free access to the work site in the framework of on-site apprenticeship.

I call my proposal the strategy of the 1%. The cultural 1% [stipulating that 1% of the budget of public building project be used for a specifically created work of art] is already in place. Why not extend this procedure to a 1% for training? It would be enough to designate a place for the on-site teaching and sharing of experience on each project. Every architect, engineer or other professional involved in making the building would have the obligation to give a public lesson and, conversely, teachers from specialist schools could bring their students onto the site to give them an experience of the reality of building, allowing them to develop another, less theoretical relation to architecture. I also had the idea of an economic and social 1%. The aim of a municipality is to keep and create jobs. The mission of an elected representative is to promote economic development, and he is always on the lookout for things that can make the city work better. But, also, the person in charge of tenders who invites bids for a project thinks that they are doing the municipality a service by choosing the most modest, which can be disastrous for local businesses. Without wishing to reform the code on public contracts, on my projects I always make sure that small companies are able to compete. All you need to do, for example, is to propose ten small painting jobs rather than one big one, which means that ten local artisans can apply. Of course, this won’t work for every job, but it is a way of fighting the hegemony of the big national companies. It is also important to get associations involved in the project. We forget that an association can make a tender. This is not, as we may be inclined to think, a case of unfair competition, for if associations receive subsidies, that is also the case with EDF and other companies that are not in a competitive environment either. In this spirit, I also suggest the introduction of a scientific 1%, for the “research” dimension is not adequately represented in the artistic 1%. The aim is to bring together and foster dialogue between open, competent individuals in the real time of the building process. The activities concerned here include user and inhabitant. Our society is being damaged by an overabundance of communication in which nothing essential is addressed, especially the question of the other as a unique entity. Everyone thinks that their way of thinking is valid for everyone else. The construction site is the ideal place for countering this tendency, for sharing desires and knowledge and building a pertinent vision of the future, in the interest of all.

“The Terrain, Frontiers and Margins of the Gaze”, by Marina Ballo Charmet

I would like to start by talking about the project titled “The Park.” It is the work of mine that most directly demonstrates the role of photography in the construction of experiences of territorial intimacy, as defined by Jean-François Chevrier in his seminar, while also bearing in mind the images by Marc Pataut (The Young Crow) and Jeff Wall’s photograph The Citizen.

The selection of images that I am going to show you concerns the temporary appropriation of social space by citizens, visitors who experimented with territorial intimacy in parks in various European cities.

I hope that these images will show how the temporary appropriation of public space by people marking their territory, transforming it into a private space for conviviality and rest, becomes an experience of intimacy. This is expressed in the construction of a mutually sustaining and inclusive urban community. The theme of contact with nature also reappears here. On the screen you can see images of parks in different cities. Bearing in mind Foucault’s words about other spaces: “We don’t live in a space that’s neutral and blank; we don’t live, die, love in the rectangle of a sheet of paper. […] They are a kind of counter-space […] These counter-spaces, these localised utopias, children know them very well. Of course, there is the end of the garden, of course, the attic, or even better, the wigwam pitched in the middle of the attic, or again, on Thursday afternoons, the parents’ big bed.”

This reminds me of Winnicott’s concept of the transitional zone that is the play area.

In his in-depth study of the mental space of autistic children, psychoanalyst Salomon Resnik gives this definition of the concept of the territory: “In Latin the word ‘territory’ refers to the ‘earth’ (terra), a measured, limited earth permanently contrasted with the sky, as the other extremity of a vertical perspective. The territory implies the idea of known or recognisable extension, that is to say that is has frontiers, that it indicates property, a specific world. A territory implies formal and juridical guarantees, respect for borders. Often, frontiers are more or less visible: in maritime territoriality they talk about hidden limits, present underwater, known as ‘lines of respect’.”

The Park started in Milan in 2006. The setting for the project was the Sempione park, where I used to play as a child. This was the starting point for a long journey through public parks in Italian cities, which was extended in other parks in European capitals, such as Hampstead Heath in London, the Tiergarten in Berlin, the Buon Retiro in Madrid, the Prater in Vienna and Central Park in New York.

Once again, it is a matter of margins and borders: to inhabit them is to inhabit an urban public park within the perimeter of the city, on public holidays. The aim of the project was to assemble relational experiences within the park, fragments of life. With these images, I wanted to emphasise the fact that the park is a receptacle of experiences and, often, a bonding factor. On public holidays these parks become play areas, an “agora.” What appealed to me was the fact that the park as receptacle gives adults the chance to be children again. The park creates this link between exterior and interior, between private and public. It is a place where you go back to play, and reconcile the city with the world of childhood.

People are not the subject. The subject is the park, inhabiting the park, the park as it is experienced. The aim of the project is not to make portraits but to bring out the full potential of the park in the city. As in my other works (Out of the Corner of the Eye and Background Noise), I put the camera at the eye level of a child of about three. In this spirit, I chose to shoot along the ground, placing myself at a non-intrusive distance.

The images are horizontal and follow in series. They progress by rebounds, without a narrative. There is often a hazy area, to give the impression of something being observed with “fluctuating attention,” almost inadvertently, in a kind of de-narration. This made it all the more important to show the “lateral,” “peripheral attention. To show both perception that is experienced more than observed, without real attention in the gaze, and the place-object, which is neutral, with no dramatic effects. These photos are the exact opposite of a general view. I am looking for a photographic view which shows that I am nearby, sitting there, and that I am looking around. I am not observing attentively. I too am sitting on the lawn. The aim to is to recapture the mobility of our gaze and the vitality of what goes on in the park.

I wanted to exclude the constructed, hierarchical aspect. I didn’t want to film a scene but to record an experience, while remaining open to the unforeseen. The result is the perception of an experience and not an intentional framing of a meticulously described element. It’s as if the camera was an extension of the eye, taking photos of what is around it on its own. That is what I mean by recording and presenting. I consider it essential not to construct the image in a rational, distanced way. In my images, I bring out the experience of the lived, the empathetic relation with the object or the place.

Cities all have a number of things in common but also features that are specific to each one. Parks are connected to their cities, they undergo their influence. It is easy to identify the continuity and diversity between the life of the city and the use made of the park. When shooting those videos in Milan, what I captured with an “open-air” reception was the absence of a house where one could receive friends, and consequently the intensity of being together, the feeling of belonging, the nostalgia for language and flavours. One could see the park’s capacity to let itself be used, to become a social space of encounter. This shared experience of strangers coming together is the point of connection, the bond: they recover their language, their music, their cooking. By spending time together, they recapture their origins, feel less alone. They are no longer separate. One element struck me as interesting: the fact that there is a peaceful sharing of space, although it would be quite wrong to idealise this. In the park people find intimacy, in the sense of being in harmony with one’s body and with the other. They also find proximity and trust. For strangers, the park is a connecting point, a link to their culture of origin, it offers the possibility of being with others, of not being alone, of laying out one’s own house and using public territory as a personal space, by recreating the experience of intimacy. The park is transformed into a space of encounter, of life experience, making it possible to break up the usual patterns and to fulfil oneself by using it in a personal, non standardised way.

It is a shared but not delimited social space that is open and closed at the same time, a “house” without walls. As a public space, Bauman argues, the park provides the opportunity “to be exposed to difference”: “Over time, being exposed to the Other becomes an essential factor in happy coexistence, capable of parching the urban roots of fear.”

In the course of this festive ritual we recover a peaceful sharing of space – not to be idealised – from which, in sublimated fashion, emerge the vestiges of the very condition of the migrant. I am talking about precariousness, travel, distance, being separated, and also the difficulty of having other places to meet.

At the start of my work on parks in European capitals, I had in mind the importance that Jean-François Chevrier attributed to the title given by Jeff Wall to his image, The Citizen: “A young man lying on a lawn in a quiet park, confident.” Chevrier read a certain irony into Wall’s image, given its inherent passivity and the “western” idea of the citizen, dominated by the active dimension.

At the same time, an urban public park or a historic park in a city are green spaces that, by their social and historical implications, reference the utopian dimension of the garden. The park reflects the socio-cultural changes that reshape our cities, framing the new practices and customs spreading through them. In my view, there is a kind of utopia to be found in what goes on in the parks of European cities.

My aim was to document ways of life by using a method that reflects the provisional and non-dramatic aspect of the unforeseen, which is an integral part of our social life, devoid of effects or special circumstances. I needed to capture empathy, recreate my “cultural counter-transfer” with regard to experiences of social isolation. In the “Excursus on the Stranger” section of his Sociology, Georg Simmel emphasises that for the foreigner the relation to space is not only the condition but the symbol of his relation to the other. Simmel speaks of the stranger not as the “nomad who comes today and goes tomorrow, but as one who comes today and stays tomorrow […] In a relation distance signifies that the close is far while ‘strangeness’ signifies that the far is near.”

To conclude this first part on my series The Park, I would like to mention these words of philosopher Massimo Cacciari, who has made an in-depth study of the city and its occupation: “The place one inhabits is not the place where one sleeps, where one eats, where one watches television and plays on a computer. We do not inhabit an apartment, we inhabit the city, but the city can only be inhabited if it offers places to inhabit. The place where we stop is a pause, like the silence in a score. There is no music without silence. The post-metropolitan territory, which does not and cannot know distance, has no sense of silence, does not allow us to stop, to refuel in the place we inhabit. Distances are the Enemy.”

Territorial intimacy is a temporary and symbolic appropriation: the concept of property disappears. It is replaced by right to use public space as an experience of peaceful private life.

I would now like to show you my project Out of the Corner of the Eye, carried out in 1993– 1994, which examines territorial intimacy in relation to public space from the viewpoint of the citizen living in the city. It began with a commission for documentation from the Festival of Culture in Graz and continued in Milan and other cities. It is not literally about the urban periphery – you will see images of the city centre – but about the periphery of our gaze: what we glimpse furtively when walking in the city, what is lateral. What one might call the repressed part of the city, that which has been forgotten or neglected. The discards, the peripheral vision of the city seen from the ground, at the eye-height of a child aged about three or, as Jean-François Chevrier puts it, at dog’s-eye height. In this regard, I think it is interesting to recall something Amédée Ozenfant said about Arshile Gorky, who was interested in the earth worm’s vision of the world: “You have to huddle down and crawl along the ground. When you take up the position of someone who has just been born or died, everything changes. If we look from a height of one metre eighty, things seem to be at our service: the world is completely at our feet. But once we are lying down, the blades of grass around us become forests […] our blind egocentrism is corrected because we become aware of our position in relation to things.”

Lowering our point of view allows for proximity and, at the same time, the switching of the vertical position. Looking from above always means having mastery and control. In Out of the Corner of the Eye we find the opposite of the rational gaze. To feel empathy with a place, I need to get close to the ground, without having a rational vision. The photographs do not aim to present the place-object in an analytical and defined way, but through a floating gaze. And I quote Raoul Hausmann: “For millennia we have adapted our eye to a point of view that reflects our notions of possession, our tendencies to inferiority: we would lose our assurance of being men if we did not, with our perspective of top and bottom, small and big, maintain the natural consciousness of our superiority over our entourage, by means of a super-compensatory vision.”

For me, photography has a relation with touch as conceived by Merleau-Ponty, who said that in order to see one must position oneself like a blind man who is in contact with things via his stick. The series Out of the Corner of the Eye explores the subject of the contemporary city and the shots are lateral. I concentrate on what is on the margins and unexpected, below the immediately perceptible. I work in horizontal series. The goal is not to put the adult, vertical man, at the centre, but to recapture a child’s vision.

I study the project before going into the field, but for me the image must emerge from the empathetic encounter with the place-object, as if it rose up out of the pre-conscious. There is always a hazy zone to demonstrate the mobility of our perception. I went early in the morning or at dusk to take advantage of the diffuse, shadow-free light, and on foot, the framing arose from the empathetic relation to the place, from a preconscious demand and not rational will. The place presented itself in its neutrality. From a photographic point of view, the shots are always horizontal, along the ground, with varying hazy zones, without strong contrasts and with normal lenses, their angle close to human sight.

Another concept that is very important for me is laterality and what is out of the frame. The place-object is shown actual size, on a scale of 1:1, and loses its functional aspect. One of my objectives is to put what is lateral, out of the frame, in the centre. This gives the margin all its power.

The city opens towards an oblique marginality of the urban space and our perception. In this regard, I would like to quote the urbanist Paolo Cottino: “Nowadays, living in the city implies encounters with the unexpected and the accidental. Rules or mastery no longer dominate our relation to space and time. We need to bring to the fore the existential element that Michel de Certeau defines as “a lapse in the system, its diabolical adversary […].”

The project also includes a book of some sixty photographs underscoring breaks in the narrative. I thought it was interesting to take up the idea of “distraction,” of distracted attention, or inattention, close to fluctuating attention, the wandering gaze. I strongly believe that by breaking up narrative we can reintegrate aspects of the preconscious by reinterpreting the meaning of things. “Because with peripheral vision one sees only a somewhat undifferentiated space, one senses he or she has intuited or simply felt the presence of an object rather than seen it. […].Peripheral vision renders something one knows without seeing it directly, something one knows only by looking out of the comers of one’s eyes. […] relations and objects but dimly perceived […], their concern with that which lies on the edge of consciousness […]. Intuitively, they [the Abstract Expressionists] arrived at this type of vision as an analogy to those contents of the mind that shrink from the gaze of consciousness. In other words their emphasis on shapes approximate to peripheral vision served as a visual analogue to the preconscious or perhaps even to the unconscious mind.” (Anton Ehrenzweig)

“Does freedom lead to solitude, or does solitude lead to freedom?”, by Wiktor Gutt

I would like to start by showing you a few photographs conveying the atmosphere of the streets of Warsaw at the turn of the 1970s. They are photographs of Easter processions and express the religious aspirations of the Polish people, which were very much to the fore in the life of the secular, totalitarian state during that period. The massive presence of people in the street was also linked to official state celebrations, as we can see in those other photographs of May Day and Nixon’s visit to Warsaw in 1972.

The photographs after that were taken in the same places, very early in the morning, during an action in the course of which we painted arrows to indicate important locations on the streets of Warsaw. The striking thing about these images is the emptiness, the small number of cars or objects of any kind, the lack of information, the general greyness. This reflects the atmosphere in Poland at the time. Perhaps, from a contemporary point of view, we might interpret this informational void as a quality, a value.

At the time, when I was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, I became aware of the theory and practice of the conceptions of “sculptural expression” and “open form.”

Professor Oskar Hansen formulated the theory of “open form” and “closed form” in the fields of architecture and art. This was a utopian conception, postulating the possibility of unifying the posture of the artist-creator with that of the viewer, making the latter a co-creator. The didactic method used to teach this concept involved games on sheets of paper, and later, games in real space. Rules were established by the Hansen doctrine. Hansen used his theory to design a monument to the victims of Auschwitz in 1958–59, although regrettably it was never built.

At the same time, in the sculpture workshop directed by Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz students, inspired by the professor, were working on forms of sculptural expression aiming to go beyond academy figures or the classic exercises in composition.

As far as I am concerned, the most important aspect of this teaching was the communicational and social factor in the creative act, linked to the need to make use of the over-expression of form. We were interested in the “art of savages,” and our activities soon referred to these. The Aborigines and Papuans did extremely interesting body paintings. These paintings were not just aesthetic or formal events. They were rich in terms of both form and meaning.

Social functions, that is, the construction of interhuman relations, initiations and ceremonies, led to a communal creation. All the different members of the community took part and all of them performed a creative function. In a sense, these situations were close to the principles of Hansen’s “open form.” There were also considerable differences. Tribal communities were small groups of people who had a special relation to nature. This singular relation also applied in other areas of life – from economics, spiritual, transcendental coexistence with the surrounding reality. The construction of myths served as a point of ingress to another reality, which was often more important than that of everyday life.

The common use by these “savages” of the body as the most important and primordial medium constituted the essence of their creative activity. Instead of mimetic recreation, it was painting, ornament and body markings that gave rise to ephemeral, multivocal forms of expression, so far removed from the petrified works by European artists seen in galleries and museums. I found it fascinating.

The reality of the totalitarian socialist state that was Poland in the 1970s hampered and limited us, but on the other hand I saw it as another face of European civilisation, the disappearing alternative to which was so-called “savage” tribal communities. This was an intense and dramatic conflation of diachrony and synchrony.

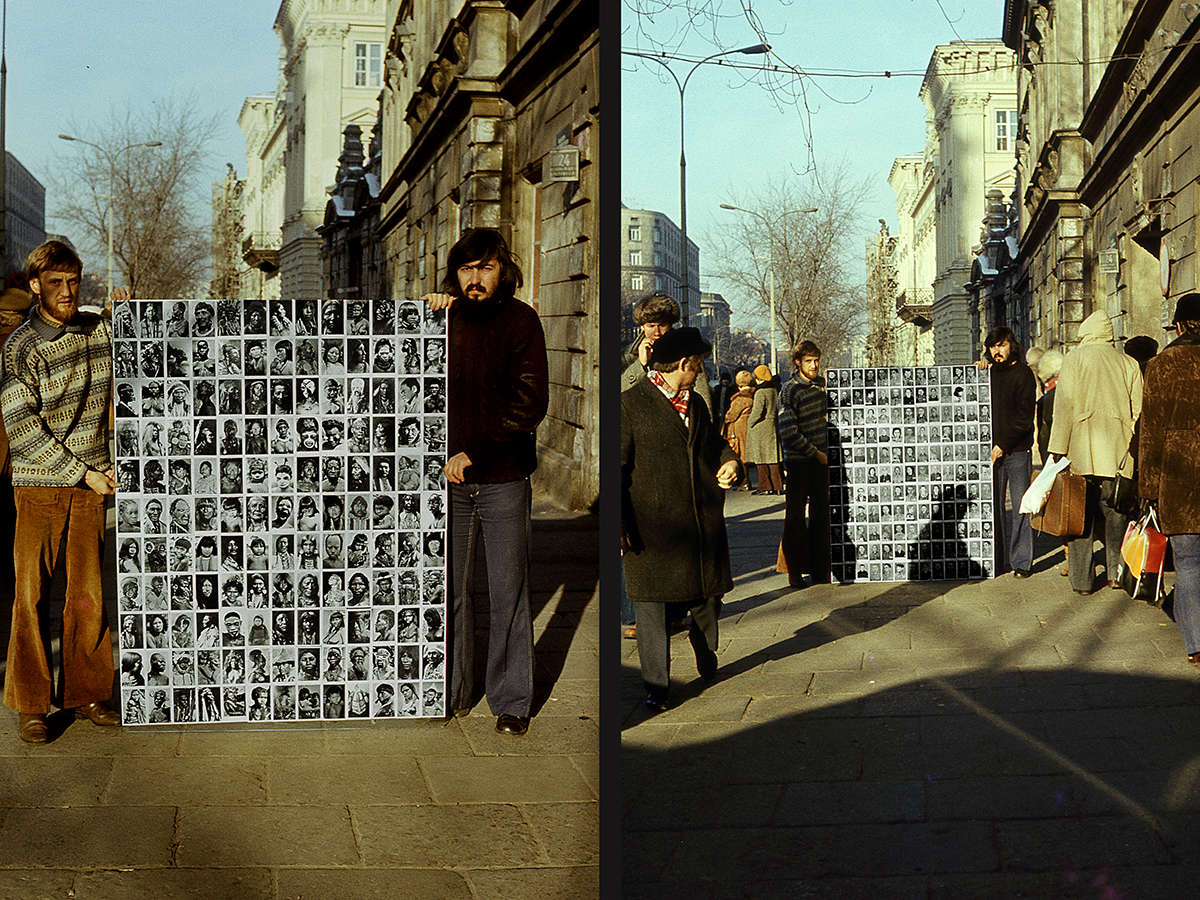

We tried to show this in 1977 with a piece of work titled Destructive Culture. We presented two sets of photographs representing, respectively, prisoners at Auschwitz and representatives of various tribal communities. As a complement to the photographic plates, we assembled documents in the camp itself and reproduced photographs found mainly in books and periodicals showing the forms of contact between European civilisation and these so-called “savages.”

Action: taking the photographic plates for Destructive Culture out of the Repassage gallery and among pedestrians in Krakowskie Przedmieście, Warsaw, 1976. Wiktor Gutt (left), Waldemar Raniszewski (right)

The communicational aspect, which was so important in my view, culminated in a cycle of works called Conversations. These were visual dialogues carried out in different ways – with sheets of paper or with all kinds of materials, including our own bodies. These ephemeral processes of dialogue were usually related photographically. My diploma from the sculpture department took the form, precisely, of a “Conversation” between two people in a block of stone. A conversation that we did not conduct in French or Polish, but in the language of “stone.” I should add here that in my view these Conversations served no purpose, they were not therapeutic, nor did they explain anything rationally. They had an intrinsic value, or rather, a value for the people taking part in them. They were disinterested acts of dialogue.

Communication as Aesthetic Value (fragment), 1974. Conversation carried out in a block of marble, photographic and written notation

A whole cycle of Conversations has appeared, and I am continuing with it at present. They are based on three complementary problematics. The first concerns the use of the art of Conversation for social groups that I see as excluded, or that have limited possibilities of expression in our culture. These are people who are psychically ill, or children.

In 1976 I decided to get a job in a psychiatric hospital. In the corridors there I carried out “plastic activities.” Patients used to doing drawing as art therapy, accustomed to the therapeutic commentaries of the psychologist and psychiatrist, quickly came to accept the new formula constituted by the Conversation via drawing. What was very important during these encounters is that the traditional hierarchical relation – sick/well, patient/doctor, normal person/abnormal person, responsible/irresponsible, ceased to apply. The Conversations were carried out in silence in the hospital corridor and not in the room where the art therapy sessions were usually held. The other patients were witnesses. There was a silent incomprehension between us, as well as the feeling that something important was happening. The absence of commentary and silence have become a particular kind of taboo. When, unwittingly, I answered someone by verbally describing what I was drawing, the intensely awake patient had a fit of hysteria.

The second problematic concerns the Conversations with children, which we called “Children’s Initiations.”

To begin with, we transferred this notion of initiation towards children, in the sense that we were trying to make them receptive to the visual language of form, space and colour. But a reversal soon occurred: it was the adults who were being initiated into the reception of children’s creations and into the aesthetic and deeply spiritual messages that flowed from them.

The project began with the drawings made in common on sheets of paper, then continued in the form of carefully prepared events during which the adults allowed the children to paint their own bodies. At first, this was done in family homes, involving friends’ children, and then only with my own children, and later on with communities of children. The role of the adults was limited to the creation of conditions in which the children could act, and the attentive accompaniment of these events. A film and photographic record of these “initiations” was kept.

I would like to point out that the whole cycle of “initiations” was eminently creative in character. Through their activity the children formulated messages that could be described as increasingly conscious and autonomous messages, or even as artworks made in a processual manner. In principle, these were not didactic or therapeutic events. During the years that followed, paintings were also made by small groups of children. The auto-creative aspect of these activities was subsequently enriched by the practice of dialogue between individuals.

The time of early childhood also offers forms of bodily expression that have the archetypal quality so characteristic of tribal cultures.

Their active use paradoxically brings into play the polar opposite of the body’s physical dimension, that is, sublimation and spirituality.

This concerns children up to the age of six who are still partly in another reality and who are thus able to experience it if given the possibility.

A third, parallel problematic also interested me. These were Conversations in which I myself took part and which, for me and my friends, were auto-creative.

At the beginning they were quick exercises done in all kinds of materials, chosen in an impromptu way. That was the case, for example, with the Conversation on the theme of the violin. Our activity – that is to say, our successive declarations – were a spatio-temporal commentary on the instrument, of the kind we could have made to describe a sculpture.

At the same time we had these Conversations which, similarly to the Children’s Initiations, were carried out by means of drawing on the medium constituted by our own body. The was the case with the Conversation about the colour red which served as a commentary on the political situation in Poland, or the Syncretic Conversation inspired by Aboriginal art, the Conversation with Waldek and Zula, the Conversation with Waldek and Chrominski, the Conversation with Kuba and Zula, the Conversation with Jadwiga. Most of the time, these events continued all through the night. Their duration and our tiredness in the moment meant that we felt completely cut off from the reality around us.

At the same time, the construction of each Conversation was always similar. Usually, we would be sitting in front of a black ground. In front of us were a mirror, a camera on a tripod, and candles, which were often the only light source. We didn’t comment on our paintings. Afterwards I would sometimes assemble tableaux using photographic material. This set of images was like a certain kind of recreation of our encounter.

Of all the Conversations, the most important and most relevant experience, in my view, is the Big Conversation with Waldek Raniszewski. This began in 1972 in rather spontaneous fashion. It was an improvised painting, done using six colours, on my friend’s face. This painting struck us as particularly significant. We decided to repeat it and photograph it. That is how a whole series of our “declarations” came about. The Big Conversation became an event which continued over time and took place in a variety of locales. My friend’s painted face took the form of a little cube, which we later extended to 2 x 2 x 2 metres. A geometricised representation of Waldek’s head was then made, black on the outside and, on the inside, painted in the six colours derived from the first face painting. The internal space of the cube became the backdrop of the interactions that we invited our colleagues and teachers to participate in, thus becoming the co-authors of our Conversation.

The development of this event took on the polyphonic character of a construction rich in multiple meanings. We were no longer subject to linear time. The individual “declarations” gradually created new contexts, which we could assemble as many times as we wanted.

In 2008 I recreated the first painting I made on Waldek’s face – he died two years before that – on Adji’s face. She is a black woman from Mali. Adji was well aware of the person on whom the work was originally done. During the recreation, we saw that the painting itself had a very intense sensual effect on her.

The time that has passed since I started my activities in the 1970s has brought freedom to the people living behind the then Iron Curtain. This silently cherished freedom, so highly valued in an oppressive state. This freedom that a small number of artists managed to win at the cost of their total marginalisation from public life. This freedom and independence of thought that their potential public could not attain.

Today, with the reinstatement of the “informational metabolism” – this is the term used by the eminent Polish psychiatrist Antoni Kempinski, who saw its degradation as a factor leading to schizophrenia – this freedom is still threatened. I am thinking in particular of commercialisation, which tries to transform all aspects of human existence into a consumer product. The new threat to freedom paradoxically coincides with the attempt to achieve it through new technologies. Communicating without censorship or border controls, the virtual communities of the Internet have become a chorus in which it is difficult to hear the soloists.

Art as an elitist manifestation – in the positive sense of that term – is sadly becoming extinct. By elitist I mean silent, concentrated on a small group of people, for whom the art of dialogue makes it possible to deepen the feeling of mutual coexistence and safeguard against dilution in the ocean of information all around us.