Dans le cadre d’une conférence tenue par l’anthropologue Esmail Nashif autour de Death, dernière série d’Ahlam Shibli, le commissaire d’exposition et historien de l’art Ulrich Loock présente la rencontre et contextualise ce travail récent dans le corpus de l’artiste.

![Vue de l'exposition "Ahlam Shibli. Phantom Home [Foyer Fantôme]" au Jeu de Paume. Ahlam Shibli, série "Death", tirages chromogéniques. Courtesy Ahlam Shibli. Photo Adrien Chevrot © Jeu de Paume 2013.](../../../wp-content/uploads/2013/06/003.jpg)

Vue de l’exposition « Ahlam Shibli. Phantom Home [Foyer Fantôme] » au Jeu de Paume. Ahlam Shibli, série « Death », tirages chromogéniques. Courtesy Ahlam Shibli. Photo Adrien Chevrot © Ahlam Shibli, Jeu de Paume 2013.

Now that it is possible to consider more than ten years of Ahlam’s photographic work, it appears with increasing clarity that the different series she has produced over time are concerned with one single issue that each new work approaches from a different perspective, unfolding it, displacing it, reconsidering it under changing contextual conditions. Her single issue of concern is the issue of home. Among the questions that can be derived from her work are: what are the consequences of being denied a home, what is the price individuals or a population are forced to pay in return for claiming their home, who defines the right to a home, what are the oppressive forces exercised in the name of home and what might even be the liberating effect of the loss of home?

From the beginning of her working career as an artist Ahlam has created series of photographs devoted to people living under specific local, political, historical and cultural conditions. The paradigm of her work is film rather than the notion of the single image. None of her photographs are staged, her pictures are the result of an involvement that often extends over months or several years, and each series is generated by an editing process of choosing twenty or forty or eighty pictures from an archive of hundreds or thousands of shots.

Usually Ahlam’s work is considered to participate in the practice of documentation. It should be emphasized, however, that as far as she is concerned what is there is not positively there to be recorded. She employs photography to open the eyes, to see what is there as if it were for the first time, to recognize what is unrecognized. In ethnographic terms one might liken her position to the position of the participant observer – her subject however is fleeting in an insuperable way. In order to connect her effort to represent what is denied representation to a questioning of the notion of home, I would like to quote Santu Mofokeng, a photographer whom Ahlam greatly appreciates: “Home is an appropriated space. It does not exist objectively in reality. The notion of ‘home’ is a fiction we create out of a need to belong. Home is a place where most people have never been to and never will arrive at. Except, below that patch of mound that has a number you notice as you glide past on your way to nowhere anywhere.” The problematic nature of home, home’s inaccessibility and evasiveness, is responsible at one and the same time for the urgent need to represent what is denied representation and for the impossibility to consider representation a straightforward act of uncovering, revealing, and exposing what has been, to allude to the formula of Roland Barthes [ça a été].

Ahlam Shibli, Tal al-Saba’a (Goter no.13), al-Naqab, Israel / Palestine, 2002-2003, Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

The photographs of the series Goter picture Palestinians in their living places in al-Naqab (the Negev desert). These people live in villages that are not recognized by the Israeli state, that are not marked on official maps and where no permanent houses can be built, because the state denies a complete population the right to live on their ancestral lands and tries to concentrate them in several townships built by the state. Ahlam has expressed that condition in the following way:

Where there is a home, there is no house; where there is a house, there is no home.

To oppose the denial of recognition connected to the mutual exclusion of home and house, Ahlam represents places that the state excludes from representation. Turning into pictures what is visible but not recognized she reverses the symbolic deletion – which is regularly accompanied by physical destruction – of people and their places. At the same time her pictures disempower representation in order to avoid the reifying effect of representation’s exposure and to avoid victimizing photographically the disenfranchized. In Goter, with very few exceptions, people are not portrayed but represented as dark shapes or silhouettes, more like shadows than persons. Or the face of a person is veiled by a sheet of paper held up in front of her or a piece of cloth is placed in such a way that it leaves only the person’s feet to see. To be very clear it has to be repeated that the suspension of representation is staged within a system of representation so that the questioning of the photograph’s framing power does not result in a repetition and confirmation of the state power’s denial of recognition.

Ahlam Shibli, Sans titre (Trackers n° 8), Lakhich Army Base, Beit Gubrin, Israël / Palestine, 2005, Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

The challenge of the series Trackers is to represent a part of the Palestinian reality that the Palestinian society itself has trouble to recognize: the phenomenon of Palestinian volunteers serving in the Israeli army. The volunteers expect from the oppression state recognition and the opportunity to build a house. People who are deprived of recognition and their ancestral lands don’t know better than to invest their bodies in return for a place to live. They accept to fight against members of their own society who struggle to rebuild a homeland; in order to be entitled to a house they agree to assist in the destruction of the homeland by the oppressor and the risk to lose their lives in that course of events.

Ahlam Shibli, Sans titre (Eastern LGBT n° 22), International, 2004/2006. Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

In the series Eastern LGBT Ahlam focuses in a different context on the biopolitical consequences of the notion of home that are revealed by the Palestinian volunteers’ decision to serve in the Israeli army. Eastern LGBT is devoted to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people from Eastern countries such as Palestine, Lebanon, or Turkey who in their home countries are denied the right to live according to their chosen sexual or gender orientation. In order to escape oppression in the name of homeland values, they have to leave their native societies, seeking opportunities to feel at home in their own sexual bodies in a foreign place.

Ahlam Shibli, Sans titre (Dom Dziecka n° 30), Dom Dziecka. The house starves when you are away, Pologne, 2008

Dom Dziecka Na Zielonym Wzgórzu, Kisielany-Źmichy, 28 septembre 2008, dimanche après-midi. Pendant le déjeuner dans la salle à manger, Roksana Jeronimiak, Magdalena Zubek et Emilia Dmowska partagent une chaise, pendant que Jakub Urbański et Adrian Bieniak sont assis au bout de la table. Daniel Kopeć, Krzysztof Zubek et Tobiasz Perkuć ont rapporté leurs assiettes vides et retournent à leur place.

Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

Dom Dziecka. The house starves when you are away shows children who grow up away from a family home in an orphanage, where they create a new home and a new social body. In both cases Ahlam’s photography traces ways in which people react to the denial of an accommodating original home by establishing values and ways of living that divert from the majority’s culture. The withdrawal of a native home, even though involuntary and certainly painful, is revealed as bearing the potential of liberation and auto-determination. Inversely it emerges that the people depicted in Goter are not only denied their own home by the Israeli state but through that denial also excluded from contemporary redefinitions of the notion of home. This series confirms a notion of home that is firmly connected to a territory even if that notion should turn out to be illusionary.

Ahlam Shibli, Sans titre (Trauma n° 2), Corrèze, France, 2008-2009

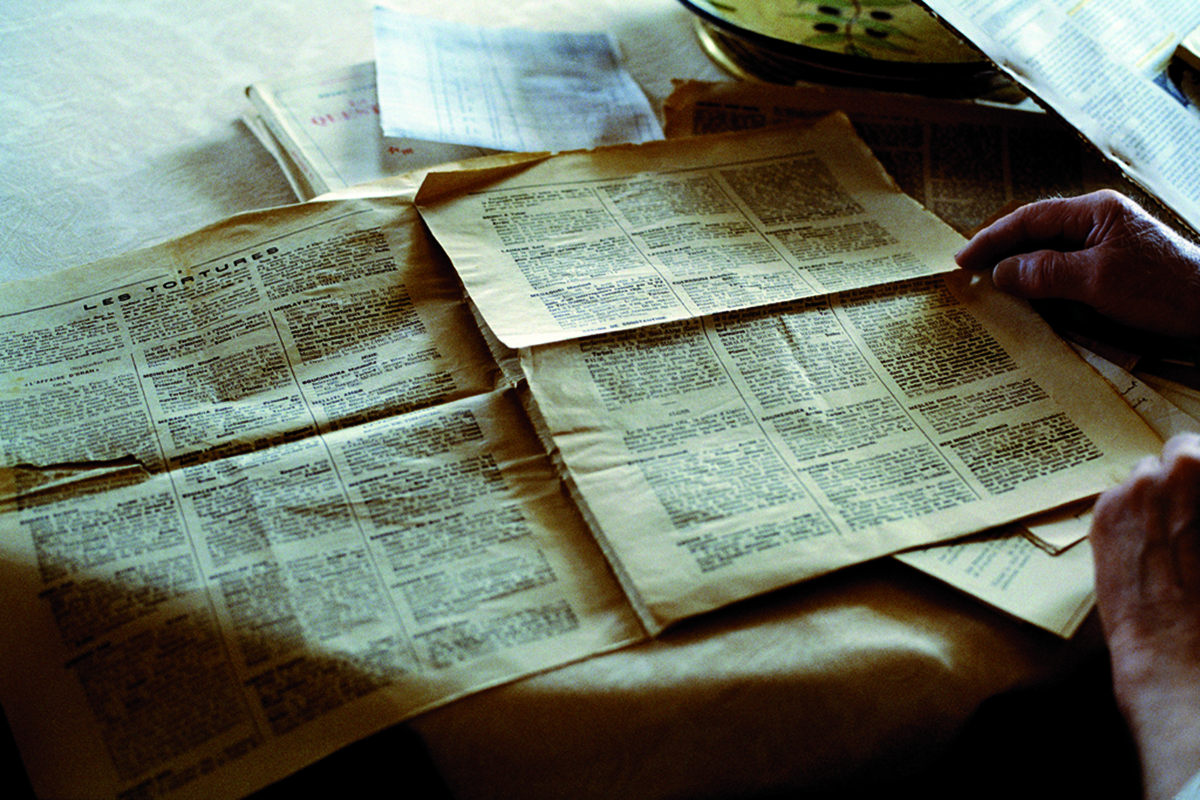

Chanac-les-Mines, 18 juin 2008 Daniel Espinat, ancien membre de l’Armée secrète, montre des documents sur la torture pratiquée en Algérie par l’armée française qu’il diffusait clandestinement en Corrèze pendant la guerre d’Algérie.

Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

In the work Trauma home appears as a notion of auto-affirmation and the exclusion and oppression of others who in their turn demanded the right to their own home. In the city of Tulle, Ahlam noticed that celebrations commemorating those who fell in the fight for the French homeland, the victims of Nazi occupation and the martyrs who lost their lives pour la patrie were connected to commemorations of military personnel who lost their lives in the colonial wars fighting against those who struggled themselves against occupation. In this series it appears that the notion of home has the potential to turn into a tool of political and social oppression – which takes us back to the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian homeland.

In her most recent work, Death, Ahlam focuses one more time on the biopolitical consequences of the Palestinians’ fight for their home. The work is concerned with the representation of martyrs and actors of martyrdom operations, men, women and children who lost their lives as a consequence of the Israeli occupation of Palestine or used their own bodies to carry explosives aimed at Israelis. The martyrs didn’t have anything to invest in support of the homeland except their bodies – for them it is true what Mofokeng says, they arrived home only “below that patch of mound”. All these people are dead which makes it impossible to represent them photographically. Ahlam therefore chose to take pictures of representations of the dead that cover the walls of Palestinian streets and guest rooms, posters, photos, graffiti – representations that confirm and mythologize the continued presence of the deceased in the Palestinian society. Turned into a representation of representation in a certain way photography gives up its power of representation. It does not represent anymore that which is excluded from representation, it does not function to recognize the unrecognized, and it does not need to be concerned with avoiding reification and victimization through photographic representation. It collapses into virtual congruence with what it is the picture of. In that way it might be said that photography, turned into the representation of representation, matches the immediacy that characterizes the martyrdom operation, the killing of Israelis through a Palestinian body carrying explosives: the total negation of the other equals the total negation of the self, death is shared death, epitomized by the mixing of the flesh and the blood of the self and the other in the blast.

Ahlam Shibli, Sans titre (Death n° 33), Palestine, 2011-2012

Camp de réfugiés de Balata, 16 février 2012. Photos du martyr Khalil Marchoud qu’est en train d’épousseter sa soeur dans le séjour de la maison familiale. Sur l’affiche, cadeau des Brigades Abu Ali Mustafa, il est présenté comme le secrétaire général des Brigades des martyrs d’al-Aqsa à Balata.

Courtesy de l’artiste, © Ahlam Shibli

Visuel en page d’accueil :

Ahlam Shibli, Untitled (Dom Dziecka nr. 4), Dom Dziecka. The house

starves when you are away, Poland, 2008, gelatin silver print,

57.7 x 38 cm

Dom Dziecka Trzemietowo, 7.10.08, Tuesday afternoon.

Gracjan Schmelter and Tomasz Brzadkowski posing for the camera

with the sculpture in front of the entrance of the Children’s Home.

Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli