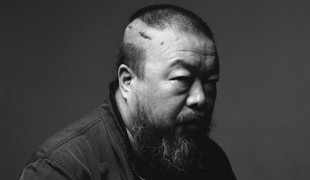

Alison Klayman’s documentary Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry has been released in French cinemas. Her film emerged from a long-term process. In 2006 she moved to China, and in 2008 she first met Ai Weiwei. This first feature documentary is made out from footage shot between 2008 and 2010. During this period, Ai Weiwei’s political activity and community involvement reached its climax. Alison Klayman accurately shows how the artist carries out his vision and action right to the end, in other words until he was imprisoned on April 3rd 2011 and prosecuted by the Chinese authorities. He was later released under surveillance and banned from leaving Beijing, with no freedom of expression.

The Jeu de Paume is proud to show Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, a few months after the exhibition curated by Urs Stahel “Ai Weiwei – Interlacing”. It was the first major exhibition that presented both photographs and videos by Ai Weiwei. It foregrounded Ai Weiwei the communicator, the documenting, analysing, interweaving artist who communicates via all existing channels.

Alison Klayman’s film enriches our understanding of Ai Weiwei as a full-time activist-artist. She made this film out of Ai Weiwei’s life, from a very humane point of view, showing the artist’s relationship with his relatives (his mother and his son), friends, collaborators, fellow artists, curators, journalists, his followers on Twitter, everyone who comes across him, and even the cats that wander around his studio… But Alison Klayman goes beyond this approach, by showing how Weiwei came meet the Sichuan Earthquake’s victims, how he dealt with the official Power and how he went head to head with the Chinese Police.

Le magazine Dear Alison Klayman, when you first met Ai Weiwei, in 2006, he was still involved in the Bird’s Nest architectural project for the Olympic games. But after designing it, in collaboration with the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, he publicly expressed his regrets of taking part in this event, because ordinary Chinese people were left aside from it, when not simply expropriated.

Your documentary shows that Weiwei is truly attached to his country. So, was the Bird’s Nest some kind of disillusion or disappointment for him? Did you hear him talk about it? Wasn’t it the beginning of his activism against the Authorities with an international tribune?

Alison Klayman That’s a really great question that I have talked to Ai Weiwei and others about. Weiwei said that he views himself as being politically involved long before the Olympics, through his underground books and the alternative art shows he curated. Yet from the time he started using the Internet with his popular blog, which coincided with the time he spoke out about the Olympics, his political thoughts and organizing had a much bigger reach.

Then, the fact that he was involved with the design of the Bird’s Nest made him a natural interview subject for the press in the run-up to the Games. He does not see it as a big defining moment in terms of how he viewed the State, but rather it was an opportunity for him to speak his mind and be heard. He told me: “I just simply expressed my feeling towards what kind of Games they will be, but of course I always give out my opinions in this sense and I didn’t expect the newspaper would put: ‘the designer boycotts the game’ which is very big news …then the Games itself proved I was right and I made a very clear decision and I am very proud of that.”

On the other hand, when I interviewed others who lived in Beijing at that time, they said that in the early 2000s when Beijing won the bid for the Olympics, there was a small sense of hope from the intellectual class, that perhaps this could be a sign that China was moving towards more openness and international cooperation. Weiwei acknowledged that, too, when he told me: “We all supported the Olympics from beginning, I think that’s a chance for China to really become a member of international family to share the same kind of values and to be more open.” But at the same time, he pointed out, his involvement with the design team of Herzog and deMeuron for the Bird’s Nest is not the same as being invited by the government, and once he saw what the Olympics were really going to be like, he felt he had a right to speak out.

Le mag How did your project start? How did you collaborate with Ai Weiwei and how did you manage to get close to his intimacy so naturally?

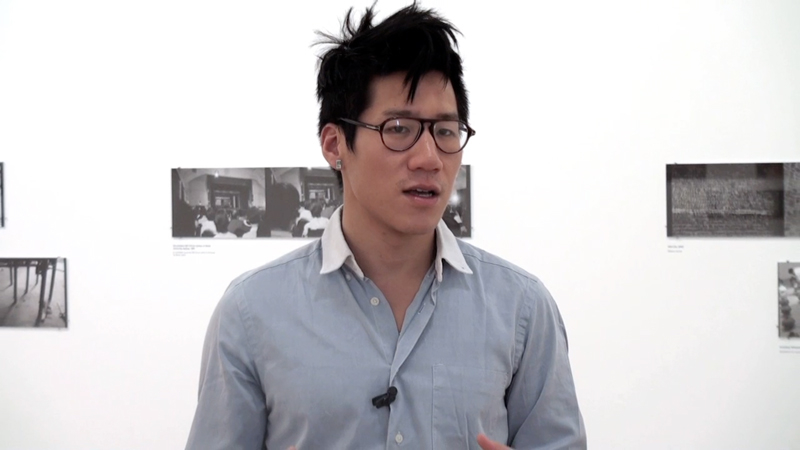

AK I was living in China working as a freelance journalist for a few years when, in 2008, I had a chance to meet Ai Weiwei. My roommate Stephanie Tung was curating an exhibition of his photographs for a local Beijing gallery. This was a particularly personal body of work for the artist: a selection of several hundred images out of the over 10,000 photos Weiwei took during the decade he lived in New York City, from 1983-1993, I sometimes joked with Steph that she was essentially curating content that today might have been Ai Weiwei’s Facebook photo albums.

Needless to say, this was an amazing collection of images to browse through at the kitchen table in my apartment in Beijing, and I first came to know Ai Weiwei through the stories these pictures told. At the end of 2008, Steph asked if I wanted to make a video to accompany the exhibition, to tell more about this period of Weiwei’s life and also to further explore the role of photography in his artistic practice. I prepared my equipment and myself to meet this man on a clear-skied day in early December.

This is how it came to be that I was already waiting with my camera in hand when I first met Ai Weiwei. He came into his office and I was introduced: “This is Alison, she’s going to make a video for the show.” Ai Weiwei nodded and our journey together began.

Weiwei’s demeanor was confident and open. He both commanded the room but also liked to joke around and put people at ease. I think he enjoyed the position he now found himself in- looking through his old snapshots of Chinese youth coming of age in New York, answering the questions of two young Americans coming of age in Beijing. What a different two decades makes.

Since I came into the project with so few preconceptions about Weiwei, I had so many basic questions that I would ask him. Perhaps because he appreciated that I was asking with an open mind, Weiwei was remarkably unguarded in his answers. When I review the footage from those first few weeks, I am amazed at how our conversations cut to the core of what would come in the following years.

Le mag Did you encounter problems with the Chinese police when you filmed outside Weiwei’s studio?

AK I did not run into problems while shooting the film in Beijing where I lived and worked as an accredited journalist. When they installed the surveillance cameras outside Weiwei’s studio in 2009, I was nervous, but there didn’t seem to be a heavy consequence for visiting Weiwei. I even filmed the vans where the plain clothes officers were parked outside his home.

The tensest moments of shooting were during the two trips when I accompanied Weiwei to Chengdu, in Sichuan Province, when he was going to file a complaint about his police assault. On those trips he was going to various local authorities in order to file complaints or lawsuit requests, so we knew it was likely we would run into difficulty. On both trips, at some point in the shooting I was pulled aside and asked to delete footage, or had tape confiscated (nothing important was ever lost, though, thanks to a habit of frequently changing tapes). I was never concerned about my personal safety, however. My primary concern was what was going to happen to Ai Weiwei and his assistants/volunteers/associates who were all Chinese citizens and faced more serious consequences.

Le mag Ai Weiwei is always surrounded by many collaborators, including Zhao Zhao, his personal videographer. Weiwei himself is always taking shots with his cell phone and “tweeting”. Could you tell us about your experience of making a documentary about an artist who documents his own actions and thoughts all-day long?

AK On the one hand, it was kind of incredible; it was almost like having an “open source” documentary subject, since he was constantly putting out his own documentation and commentary of his own life through tweets, photos, artworks and underground films. On the other hand, it could be very overwhelming that I had thousands of posts and photographs to go through, in real-time or doing searches online after the fact, and I spent a lot of time during the edit combing for this kind of material that might fit the film. For example, for a very important scene that we were cutting I might look to see what he posted online from that day. Sometimes I even had filmed him tweeting, and in those cases I tried to be as accurate as possible and show the actual photo or tweet from that moment in the film.

I always knew his online presence would have to be represented in the film, and during the edit we decided to have his Twitter feed run throughout, almost like a character of its own. Our rough cut had even more tweets, but we narrowed it down to the ones in the film to make sure it didn’t interrupt the flow of the story, but rather enhanced it and sometimes gave you new information. It certainly helps the audience understand how he uses social media and also reinforces his voice and attitude.

Le mag Ai Weiwei lived in NYC for more than ten years. Even if his work is closely connected to the Chinese political context, did you feel that he’s somehow speaking an international language? Apart from an unequivocal attack towards the Chinese official power, do you think that his work can echo in Western democracies?

AK Absolutely. I think sometimes he is criticized for almost being too “Western” in his methods of expressing his discontent with the system in China. The way I have come to see him is as a very Chinese artist: he is Chinese by birth and remains a citizen there by choice; he carries a deep knowledge of and interest in his country’s material culture and arts; and he is profoundly concerned with his country’s past, present and future. But at the same time, he is also a global figure, an international symbol for digital dissident, creative expression and critical thinking, really a public intellectual with a punk rock attitude. To me, you cannot underplay his Chinese-ness, but because his work is also so universal, I think it is better to classify him as international as well as Chinese, rather than making a distinction about “Western” vs. “Eastern.”

Le mag Didn’t you feel caught up sometimes in a huge business of subversion led by Weiwei? How did you keep your own independence and point of view? You must have had a lot of rushes, photographs, internet raw material… The editing was a crucial step. What was your personal guideline to the final edit? How did you proceed ?

AK I always saw my role as very different from his art assistants or other hired collaborators. I felt my documentary was important as an independent look at Ai Weiwei, and he always regarded my project as outside of his control and very much a product of my own artistic and journalistic interpretation. Although he gave me a lot of access and shared a few of his own films and personal photographs with me, the majority of the film was from material that I shot. I also did not consult with him about who else I interviewed for the project, and I did not show rushes or early cuts of the film with him until I screened the fine cut for him a few months before Sundance. To his credit, when he saw it the first time he didn’t ask for a single change.

Le mag With your documentary “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry”, you won the Special Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. Would you consider that your own work is part of Ai Weiwei’s message for reactivating Freedom?

AK I see the film as trying to provide audiences with a portrait of Ai Weiwei and his activities and concerns over the last few years. I didn’t start with assumptions about who he was, and knowing that he is such a media-savvy personality, I approached the whole project as an investigation, trying to gather many clues about him. For example, I didn’t just interview him once and take his answer at face value, but rather I often filmed him being asked about the same topic dozens of times by different people (art world curators, Chinese and international press, friends and family, etc.). This helped me eventually draw some conclusions, but I really didn’t make those kinds of decisions until the edit. By then, I felt I had discovered that Ai Weiwei was an artist who was very genuinely concerned with freedom of expression, so that had to be conveyed in the film. I have to say, as a filmmaker and journalist, I am also a supporter of freedom of expression, so I am proud that this is an organic and genuine message of the story in the film.

Le mag Did you hear from Ai Weiwei recently?

AK We are always in touch via Twitter, which is great because I see how he is following the trajectory of the film around the world as he retweets individual reactions to the film, or articles about the film’s release and awards received. We also text and occasionally speak on the phone. I just talked to him last week after the Oscar Shortlist for Best Documentary Feature was announced. He was marvelling at how far the film has gone, how many languages it has been translated into (over 20), how many conversations it is sparking all over the world. We chatted about some of the different reactions I found in different countries, and also about his current situation.

Authorities are still holding Ai Weiwei’s passport even though his year of “bail conditions” ended on June 22, 2012. He has lost all appeals for his tax case, and authorities technically took away his business’ license to operate. He is under much more pressure and police control than the years I spent filming him. He is still working on new projects and artworks, and has major international shows including one in Washington DC right now that are opening around the world (though he cannot attend them). He still believes that the causes he fights for are important, though, and that the Internet is the best hope for promoting free expression and change in China. He just is not sure about the hope there is for his own personal fate, and whether he will be allowed to travel anytime soon. They purposely keep him in this state of uncertainty, he says, and that is the most difficult.

You can still write to him any day on Twitter. His Twitter handle is @aiww and I encourage audience members to write to him after seeing the film to share their thoughts.

Le mag May you tell us a few words about your next project(s) ?

AK As for me, I am developing new film ideas while I am still very busy traveling with this documentary around the globe. I hope to do more stories about themes in this movie: Chinese culture mixing with the rest of the world, freedom of expression, how the Internet is shaping our world. I also want to continue to do films with strong engaging characters.

Links

Alison Klayman, official website

« Ai Weiwei, Never Sorry : portrait d’un artiste chinois dérangeant » by Pierre Haski

« Ai Weiwei : Entrelacs » at Jeu de Paume

Ai Weiwei @ Jeu de Paume’s bookshop