Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Figures with Tania Carl), 2011-2012

© Valérie Jouve/ADAGP, Paris 2015. Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris

Marta Gili — You studied anthropology and sociology before enrolling at the École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles. How did you come to photography? And how did the change of disciplines actually take place?

Valérie Jouve — The anthropology research I did in the Lyon suburbs – in La Mulatière and the Les Minguettes housing estate in Vénissieux – focused on what was called the “second immigrant generation”. Rather than stressing the fact that the people concerned have a dual culture, this label identified their history with that of their immigrant parents while paradoxically locking them into the idea that they had to adapt to the culture of the country where they had been born. One of my sociology teachers pointed out to me that the photos I had taken to illustrate my dissertation were at odds with my analysis, because I had photographed my subjects individually and thus “out of context”. The interviews I had done with them had confronted me with personalities and mindsets that had nothing to do with this theoretical second generation, and this was something that echoed my personal background. I grew up on a housing estate in the suburbs of Saint-Étienne, a real melting pot where we shared working-class values that went beyond our ethnic differences. So contact with these people took me back to imaginative realms going beyond the strict social framework. This was an aspect I would explore later on in my Characters, which were attempts to do away with preconceptions: the power of the person concerned has to do with the singularity of their presence and way of being, quite apart from their status or social background.

These initial contacts with photography, together with my reading – Michel Foucault in particular – led me to understand that I was trying to challenge the limitations of anthropology, which, along with its near-mandatory co-discipline, sociology, underpins our modern social classifications. A sociological investigation tends towards a result based on argument and a conclusion that synthesises the findings. But in lived situations I see only movement, change and uninterrupted transformation. Through images I try to second-guess the standard responses and undermine the logical explanations of the social sciences, while at the same time creating a less rigid relationship with the world and finding a slightly more poetic language for expressing my own relationship with it. All that I’ve kept of the sociological investigation, finally, is the methodology: the interviews took the form of conversations with the people I photographed, who were often willing contributors to my work.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Characters with E.K.), 1997-1998

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

Pia Viewing — You began your photography in the late 1980s in Saint-Étienne, with pictures of places marked by industrial collapse: the end of an era. Because they’re in black and white and because the people are shown in the course of their everyday activities, that early work is still very close to documentary. So collaboration with your “models” was there right from the start.

VJ — Between 1987 and 1990, when I was studying photography in Arles, I did a project in the Saint-Étienne mining area: people, neighbourhoods, buildings and so on. The mise en scène was still minimal: the people were ready to play along – opening a door, leaning on a wall, coming downstairs, etc. Rather than “models” I prefer to say “characters”, because they’re actors embodying an idea. Already the bodily actions were challenging the places and the space, in the same way that there was a clear urge to find a living, physical equivalent between bodies and buildings.

MG — The concerns that would become constant factors in your practice seemed to take shape very early: working outside the standard settings, pointing up the invisible personal connections that arise in the course of working together, probing the power and the ambiguity of the dialogue between bodies and architecture.

VJ — Yes, I’ve always been obsessed with the alchemy between the Other and oneself, between the space and the person, between the collective and the individual. During that same period, the summer of 1988, the sociologist Albane Fayolle asked me to back up the work she was doing for a town planning agency on Nemausus – the social housing project designed by architect Jean Nouvel in Nîmes – with on-site portraits of the residents. The job mainly involved observing the way these residents adapted to this very singular building. This was a commission that I don’t see as being on the same level as my other work, but that was when I began to think about a different approach to the photographic portrait and the figures began to converse with the space around them. The traditional portrait stresses an identity, whereas I felt that I was more interested in setting a body of individuals against the body of the Jean Nouvel building. So I used mise en scène, because I wanted our collaboration to express as closely as possible the interchange with the architecture; I didn’t ask them to smile if they didn’t feel like it – just to take the time to be there.

PV — Since the early 1990s the artistic approach has drawn increasingly on mise en scène. By that time the use of colour film was fully integrated into your work. In the images we see a growing interest in a kind of narrative in which the presence and expressiveness of the person are more intense, notably in the Untitled (Characters) group.

VJ — Colour seems to have led to that, but it wasn’t my intention at the start; it wasn’t conscious. I naturally went to black and white for the mining town of Saint-Étienne, which I saw as still focused on its industrial past. Black and white reinforced this backward-looking aspect, and worked as a reminder of the blackened nineteenth-century city.

Valérie Jouve – Untitled (Situations), 1997–999

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

I opted for colour when I got beyond the idea that it necessarily induced a particular artistic intent. At the time, lots of photographers were using it for its own sake, even to the point of tonal saturation. But my interest in the image is a long way from that kind of concern. My first try-outs with colour date from 1988 – three photographs, each showing a mine building in Saint-Étienne. Oddly, they looked greyed: their colours were faded, as if the dust from the mines had run into the light, as a woman from Saint-Étienne pointed out to me one day. Even now there’s still something of those tones in my images, which are shot through with that slightly bluish light. Once I realised that I could neutralise its garish aspect, I was less frightened of colour. And it also helped me get free of that backward-looking thing.

PV — In Characters, the person is shown almost life-size, in fairly tight focus against an open backdrop. The figure-ground relationship is disturbing because the body is striving to wrench itself out of this environment – often an urban one – and get free of it: each “character” generates an event in that he or she triggers a single, singular situation. They literally disturb the viewer with their attitude, their gestures or their bodily position. Whether the character is in front, profile or back view, there’s a confrontation with the viewer.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Characters with Josette), 1991-1995

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

VJ — Characters started with Josette in 1999, in Marseille, where I lived for getting on ten years. The first image [p. 18–19] marked the culmination of several years’ research begun in Saint-Étienne: here the body asserts its singularity very clearly. I felt that the physicality and corporeality of the images really worked. The choreographic poses that typify Characters have less to do with behaviour than with attitude: behaviour is defined within a group, in response to a set of codes, whereas attitude is a personal stance towards the world. At first I chose my subjects for their ability to personify an idea of resistance to their environment and to the standardisation of urban places. That choreographic language let me create a space of freedom, move back into the city as a place to inhabit, and explore alternative ways of occupying it. My main artistic goal was to generate movement – a rhythm, a dynamic, and a sonority in the musical sense. I didn’t yet have the cinema in mind, even if I was already putting images together mentally. I wanted to make the tone and energy and vivacity of the city tangible, rather than just offer a description of it.

Valérie Jouve — Leaving the Office, details, 1998-2002

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

MG — Choreography was a core part of your oeuvre until the early 2000s. The Leaving the Office series was the result of recording the mechanical movement of bodies exiting their place of work. The series reminds me of a video made by Harun Farocki in 2006, Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzehnten (Workers Leaving the Factory). Each of the monitors shows a film by a filmmaker or an anonymous amateur: documentation of people leaving a factory, and bodies moving out of a standardised space.

VJ — When I was living in Marseille, I spent a lot of time with dancers and saw lots of performances ranging from Pina Bausch to Meredith Monk – not to mention Trisha Brown, who was the choreographer who impressed me most: she absolutely merged with the space she was in! It’s true that in Leaving the Office, there’s a choreography of standardisation in the rhythm of the bodies – bodies I decontextualised so as to exaggerate their objectivisation. When I took the pictures outside buildings in the business districts in Paris (at La Défense) and New York (near the Twin Towers, before they were destroyed), what I was seeing seemed quite strange: the people leaving their offices didn’t seem to be there, in their bodies – as if in their minds they were still inside the building. So in order to concentrate on this simple idea, I eliminated the architectural elements: it seemed to me that by establishing the setting these elements took the edge off the harshness of the situation. The grey ground I set the people against was enough to recreate the ambience of the office buildings, which are basically grey architecture, all glass and mirrors. In my work I try to communicate a feeling, something to be felt rather than understood. That’s why choreography and musicality, in the rhythmic sense, come first in a lot of my compositions. In recent years my images have calmed down, leaving room for a more contemplative element; but dance and music are just as important for me as ever.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Façades), 2000-2002

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

PV — Your tireless exploration of the connections between the human figure and urban space has given rise to several series, among them Characters, Situations and Facades. These corpuses change constantly, though, both because you keep adding to them and because you endlessly reorganise them in your exhibition spaces. Seen from this point of view, the time-bound photographic series is quite foreign to your approach.

VJ — Yes, I like the notion of a corpus. What I make is a “body of images”. Each corpus is called Untitled, followed by a form of identification in parenthesis: Characters, Situations, Facades, Passers-by, The Street, Trees and so on. In the 1990s my work was basically structured around these different subjects. Then another space – montage – took shape when the work was being shown. A form of narrative – in the very broad sense – developed out of this juxtaposition of photos from different corpuses. Montage was a consideration right from my first exhibition at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Marseille in 1995: I feel the need to bring my images together so that they inhabit the space and create a utopian imaginative slant. All these elements fuel each other and combine to offer a visual space in which our world opens up to us without our having to understand anything. It’s just a matter of feeling, of projecting oneself and, most of all, going with the flow.

In my work the image is not tied solely to the moment of its making. And it’s not frozen, either, in the sense that it can be reinterpreted in the light of other images. I like the way images can inhabit physical and mental space over the long term: their timelessness lets them evolve in an ongoing reciprocal dialogue. That way photos I bring back after ten years take on a fresh presence in an exhibition.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Landscapes), 2009

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

Since the outset my photographic work has been focused on the relationship between the human being and his city – his living space in the broadest sense: our living space. Each image and each corpus adds something to my thinking about our cities and our relationship with them. The city is fundamental for me: it’s the incarnation of human presence on Earth, although for some years now I’ve been thinking of space in more intimate terms, with my Trees, for example.

PV — The places you photograph are always lived in. In this sense the body is omnipresent, even if it’s not actually shown in the image. For instance, Untitled (Facades) of 1997 is less concerned with urban anonymity than with the spatial organisation of the modern city. The montages of juxtaposed vertical facades induce a physical sensation of confinement, crushedness and oppressiveness that all of us sometimes feel in cities, but which a single photograph could never have conveyed on its own. Thus your own emotional experience of places provides a grounding for your thinking about urban space and ways of living in it.

À gauche : Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Characters with Andrea Keen), 1994-1995

Collection Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, Paris 2015

À droite : Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Landscapes), 2004

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

MG — Your work emerges from a tension between privacy and exteriority. In his book Mirrors and Windows John Szarkowski notes two tendencies among the protagonists of the “new photography” in America during the 1960s and 1970s: one that uses photography as a mirror onto which the artist projects his subjective vision of the world, and the other which uses it as a window onto reality. I don’t think you adhere to either of these approaches individually, but rather the two together; very subtly you place yourself in the interspace.

VJ — I try to conjure up a certain intensity I find in the living world – to construct a mental image in the sense of a projection space. The mental image is what comes after the seeing; it’s a sort of image-echo that sticks in the mind and takes on meaning once we appropriate the images. There was a time when I was really studying Maurice Merleau-Ponty and wondering about photography’s ability to convey the full force of the living world, which the visible can’t do on its own. How could the image reconstruct and recompose what the mental – the invisible – brings into being? What I do with my images happens in the transition from the visible to the invisible. My work is like documentary in the sense that the subject dictates my artistic choices. I work with what reality offers me. Even so, the intention inclines towards narrative, since what interests me is the image’s capacity to produce meaning out of reality.

For me the image provides a medium for the imaginative realm. That’s why I like to maintain the places I photograph in a kind of indeterminate zone, so I can return to their potential. Similarly, when it comes to presenting an exhibition, I try to set up a rhythm that creates the feeling of some indefinite place. The whole becomes a narrative space in which the viewer plays an active part. This image place – this place of watching – lets you project yourself into a habitable space stripped of the social contingencies. It’s a sort of existentialism to be experimented with.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (The Street), 2003

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

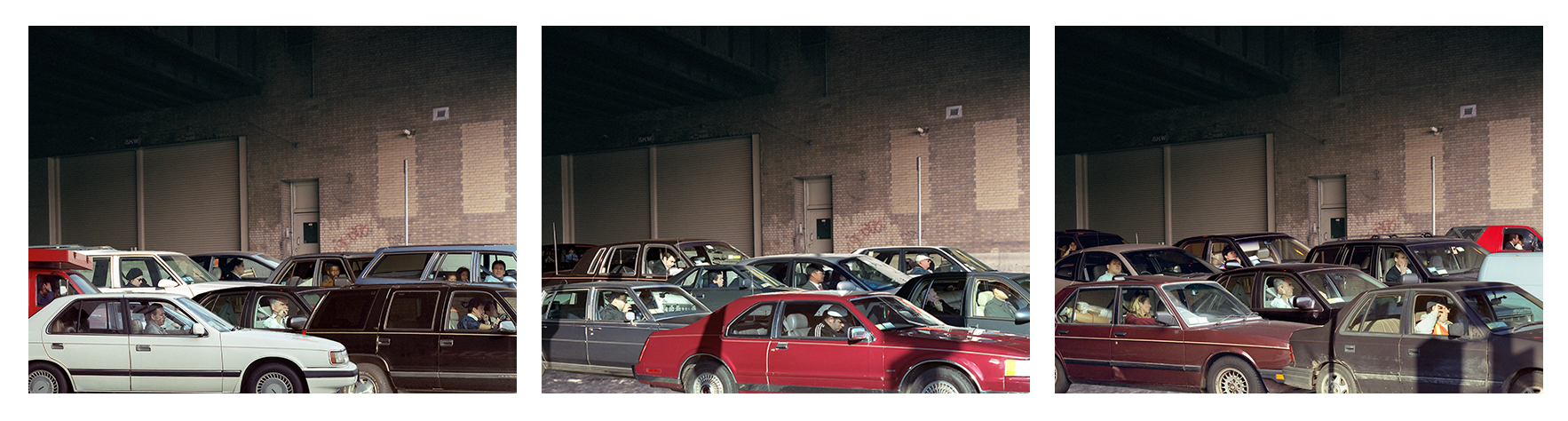

PV — In Untitled (Situations) of 1997–1999, we see that the actual image space has been worked on: the perspective has been flattened, in an indirect reference to the picture space of the Quattrocento. The effect of the montage is that the cars seem almost superposed on each other, creating a sensation of density, constraint and external control.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Situations), 1997-1999

Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, Paris 2015

VJ — It’s painters more than photographers who’ve been a help to me. My love of painting was born when I discovered the Italian pre-Renaissance painters and their ability to recreate the feeling of human scale: not a rational scale, but a more affective one that I see as better adapted to conveying our reactions to reality. I love those painters because they’ve caught the physicality of places. The explorations of the movements that followed them were oriented towards bringing order to the world, towards rationalisation of the setting and creating the illusion of space; these are questions that I find less involving.

The need I feel to maltreat illusionist perspective as the sole exact representation of the world is a starting point for my work. A single photograph offers only a single point of view, which I often feel is inadequate for communicating the spatial issues I want to emphasise. Photography doesn’t depict what is seen: it simplifies, it flattens reality and sometimes empties or drains it of meaning. The view camera, which is my favourite tool, gives me the possibility of thwarting perspectivist space and the photographic lens and creating a relationship between a succession of planes.

MG — It’s also in order to skirt the standardisation of reality that you resort to montage; in addition to the presentation of different photographs when the exhibition is set up, montage for you also has to do with the creating of an image out of several photographs.

VJ — This is true, for example, of Untitled (Situations) of 1997, which brings together people photographed separately as they were waiting to cross the street. I took the photos at two points along 50th Street in New York, at Broadway and Park Avenue – neighbourhoods close to each other, but whose residents don’t mix. Pedestrian crossings provide moments where bodies meet without touching, without interacting: the kind of urban situations that have always seemed to me foreign to human nature. As I worked on the image from inside, through montage, a shift took place and the meaning I was hoping to get came together: the image became the reflection of the tension between these bodies. The viewer doesn’t know exactly where this tension comes from, because he doesn’t know that the two groups come from different social classes. These are not the same worlds, and I like being able to confront them through my images. The American novelist Jim Harrison once asked a journalist, “So do you really believe there’s only one world?”

I’ve used montage in a number of my images, but not systematically: in my case the exception is the rule, despite the seeming classification of subjects. The first Characters, which are pre-digital, were often taken for “collages”. But they weren’t montages: they were done with a view camera. In this particular corpus only Untitled (Characters with Marie Mendy) of 1994 is a montage. The person was introduced using an internegative process. I’d photographed her on the Grand Littoral shopping mall building site in Marseille, but set against the backdrop of churned-up earth in the original image, Marie, who’s Senegalese, looked like an African in a desert setting – a real stereotype. I wanted to preserve the spontaneity of her laughter, but as I saw it, it had to be transposed into a more contemporary world. Marie and I talked about it a lot, then decided together on the setting for the final image, which still maintains the spatial confusion I like so much.

Valérie Jouve — Untitled (Characters with Marie Mendy), 1994-1996

Collection FRAC Île-de-France © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, Paris 2015

PV — The character is very expressive. She exudes a “ferocious” life force, a majestic power of resistance.

VJ — There are moments when photography can be a little bit magic, a kind of gift: something unexpected carries you beyond the initial idea. This image represents a credible situation – somebody really laughing – but it’s not at all a snapshot: Marie’s body was motionless. On the other hand, the image is not the source of this Character: Marie is this person, this life force, this resistance.

PV — The concept of body – of corporeality – permeates your oeuvre. With Trees and Figures, dating from 2006 to 2008, it arises in different terms from before. In contrast with Characters, for example, the subject is shown anchored in the soil, firmly rooted in its setting, and taking on greater volume, depth and presence. You treat your Trees like people: they have body.

VJ — I did my first portraits of trees during a residence at the art centre in Vénissieux in 2003. I felt culturally close to Vénissieux, having grown up and studied in the same region. The trees really looked like Characters to me; they were spatial markers, with the plots of land of each property being structured around them. Rather than photograph the working-class neighbourhood of the Berliet housing estate in the Bernd and Hilla Becher style – with an individual picture for each house – the urge came to me quite naturally to respond to the commission with trees. They had such power, especially at that time of the year: the smooth wood of the plane trees turned silver under the autumn sun – that magic life sometimes offers.

Since Trees, my way of imagining my work as a photographer has been changing: I’m more detached, and less proactive in terms of movement and mise en scène; I give the subject more autonomy. The shaping of an image is no longer necessarily tied to the urge to follow an urban dynamic, but rather to a desire to provide a space for contemplation. I’ve realised that presence can be powerful without being dramatic and that this also enhances the notion of resistance. Even walls are bodies. History has filled them with humanity: I sense that they are a receptacle for all the lives they have surrounded, and I try to get this feeling across as much with the image itself as with the context I establish. This is why I came up with Compositions.

Valérie Jouve — Composition # 1, 2007-2009

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

Now I want to work towards something essential, and take time for solitary observation. Formally speaking, the images conjure up moments of meditation that lead to more “cosmological” considerations. I want to show that the world is, maybe, still familiar to us.

MG — Has your subjects’ contribution to the work changed too?

VJ — My collaboration with them may have taken different forms over time, but it hasn’t changed much. It always centres around a decision taken by two or more of us about how to portray an idea, a notion of the world. Sometimes it’s the relationship with the people that becomes the subject of the collaboration, as was the case with the film Repérages, which was shot on Place des Fêtes in Paris with a group from the FRAC Île-de-France, and tells the story of a collective project; and of the recent exhibition “Cinq femmes du pays de la lune” at the MAC/VAL, which was the result of three years’ work with four Palestinian women. The film Grand Littoral was made using almost exclusively Characters I had already photographed. The connections I’ve built up with people continue; a sort of family takes shape.

PV — The verticality of Trees gave rise to a different relationship with people. In Figures they’re shown standing, full-length. From the top to the bottom of the picture.

VJ — In Untitled (Figures with Benyounes Semtati) (1997–2000), we feel the landscape, and in the image this man, who’s actually behind a metal post, becomes a body held up or sectioned by the post. This is not a montage. This photograph questions our relationship with a body that is mistreated, crushed, not listened to. The verticality of this body underscores its vitality, its resistance. The upright stance summons us to become active in the world again. The city as subject becomes secondary.

Valérie Jouve – Untitled (Figures with Benyounes Semtati), 1997-2000

Courtesy galerie Xippas, Paris © Valérie Jouve / ADAGP, 2015

MG — There’s a kind of solitude, a melancholy emanating from this image, in which the body is once again in a much vaster setting.

VJ — I think I suffer from a kind of melancholy linked to a feeling of loss, a feeling of a world that’s being rendered impossible, a world humanity is more and more cut off from by its own vanity. An African friend once said to me, “In your society you’ve forgotten how to be small.” I often think of that remark. Resistance will have to find the strength to cope with the new financial monster.

PV — Over the past few decades the new means of communication that mean we’re connected full-time – from cell phones to virtual networks – have changed the way people interact: they don’t need to move about physically anymore. The upshot is that the fundamental human feeling of belonging is being undermined by this dislocation of the body’s direct relationship with its surroundings. The corpuses Untitled (Passers-by) and Untitled (Landscapes), and the film Grand Littoral form a group of works focusing on these issues. In your exhibitions the Passers-by function as allegories of our time: each of them is walking alone, in postures suggesting a world inhabited by individuals who are in motion but not interacting.

VJ — I’d like to point out that the room I chose for the Passers-by and the Landscapes in the Jeu de Paume exhibition is the one in closest contact with the city, because it opens onto the Tuileries Gardens. It’s also the room I chose for showing two films about journeys. Journeys have a special interest for me, because they induce movement. The Passers-by are bodies just passing by. Maybe they’re embodiments of the very complex times we live in. Unlike the rest of my images, all taken with a view camera, for these I used a Leica CL 24×36 – small, light and discreet. These photos provide a rhythm I need for the exhibition montages: the smaller formats mean I can arrange them in a way that sometimes speeds up the display space. They lead us through the different territories in question and give us tools for looking at the other images.

This conversation took place on the occasion of the exhibition “Valérie Jouve. Bodies, Resisting”, shown at the Jeu de Paume from June 2 until September 27, 2015. It is also published in the eponymous catalog, Paris, Jeu de Paume / Filigranes Éditions, 2015. Curators: Valérie Jouve, Marta Gili, Director of Jeu de Paume and Pia Viewing, Curator at Jeu de Paume.

More information about Valérie Jouve solo exhibition

Buy the catalogue

« Journeys into the City »– Films in relation with the Valérie Jouve exhibition.