—

This article was first published by the College Art Association in the Summer 2005 issue of Art Journal, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 62-77

One. In 1989 Lorna Simpson made Guarded Conditions. It depicts a black woman in a simple shift and sensible shoes with equally sensible neck-skimming braids, her body rendered in three subtly mismatched images whose serial iteration proposes an endlessly expansive repetition. Yet among the six versions presented of this antiportrait 1, differences obtain between one seemingly identical set of Polaroids and the next, as if to register the model’s shifting relationship to herself. Feet are shuffled about; hair gets ever-so-slightly rearranged; and in that middle row of photographs, the right hand alternately embraces, then caresses the left arm, echoing the rhythm of the words « sex attacks skin attacks », which caption the prints.

Lorna Simpson, Guarded Conditions, 1989. Eighteen color Polaroid prints, twenty-one engraved plastic plaques, seventeen plastic letters. 91 x 131 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

In the more than fifteen years since its September debut at New York’s Josh Baer Gallery, this work has been frequently exhibited and reproduced ad nauseum. Indeed, its now-familiar reliance on the provocatively chosen phrase and the trope of the Rückenfigur to interrogate the visual production of the black female body made it an emblem —both for Simpson’s practice of the late 1980s and early 1990s and for the contested cultural terrain in which her art was entrenched. 2 As such, Guarded Conditions has been taken up by writers of various intellectual stripes, though in attempting to make sense of its matter-of-fact yet recalcitrant presence, they have time and again seized on external referents to clarify the artist’s import.

Right off the bat, in a December 1989 review, an art critic described reading a newspaper article about the brutal beating and rape of a black woman by two white security guards the day before he saw the photo-text in question. « The coincidence of the newspaper story and the piece in the gallery, » he contends, « revealed how Simpson’s work comments on the often ugly facts of life without simply reporting them.” 3 Guarded Conditions is introduced here as a studied refraction of the real; not dissimilarly, for a curator writing three years later, it would become a double-sided metonym of racial sufferance. By her lights, the woman’s isolated body invokes « slave auctions, hospital examination rooms, and criminal line-ups, » while the duplication « of the turned-back figures … calls up images of those women who stand guard against the evils of the world on the steps of black fundamentalist churches on Sunday mornings.” 4 Differently mining the same vein in 1993, a feminist performance theorist deemed the work a gesture of defiance, and in looking toward it, she, too, looked away, this time to Robert Mapplethorpe’s Leland Richard of 1980. « Whereas for Mapplethorpe the model’s clenched fist is a gesture toward self-imaging (his fist is like [the photographer’s] holding the time-release shutter), [for Simpson], the fist is a response to the sexual and racial attacks indexed as the very ground upon which her image rests.” 5

Robert Mapplethorpe. Leland Richard, 1980. Gelatin silver print. 20 x 16 in. ©The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Courtesy of Art + Commerce.

Each of these interpretations succeeds, I think, in expanding the allusive scope of the work, yet in every instance, the off-frame scenarios that the artist courts through her use of language, but just as assiduously refuses to picture, are privileged as the loci of meaning. 6 Guarded Conditions thus comes to us as a collection of iconographic details—the position of a hand, a row of sentinels, or simply the specter of black woman as victim—each unleashing a chain of associations presumed endemic to black female experience. Such readings, regardless of their authors’ intentions, effectively curtail the address of Simpson’s art in neglecting to examine closely not only what she gives us to see but also how she would orient us toward it, since even her refusal is surely meant to solicit our engagement.

What is it, then, to stand before Guarded Conditions? To encounter an image of the human body presented on a scale slightly greater than our own and in a posture not dissimilar to one we might adopt as viewers? What is it to face a figure embedded in a frame whose overall shape reinforces a gestalt, even as its bars enact an almost surgical division of the woman pictured? Does the fragmentation of her body undo any sense of corporeal affinity we might feel, and so foreclose the possibility of identification? How, in other words, does Guarded Conditions aim to interpellate, and so place us? Is the model’s placement before a white studio backdrop meant to remind us of our own framing within the white cube of artistic consumption? As she is frozen in an indeterminate space, on that nondescript platform, are we moored to the imaginary point projected by those telescoping lines of « attacks »? How are we to account for the frantic interchange between word and image, which resembles not so much a shuttling as an induction into the regimes of violence that plague the woman before us? Are we victims? Accomplices? Or mere witnesses to a series of unseen transgressions, allowed to examine the site this woman occupies, but unable to enter it given our ever-belated relation to the photographic?

What I want to argue, in the lines that follow, is that to stand before Guarded Conditions is to be suspended between repetition and difference, the visual and the sensate, the particular and the universal—those fraught intersections, which have persistently animated Simpson’s analysis of how representation stops up the significatory flow of black female subjectivity. And in this work, it is perhaps first and foremost to be caught belatedly, while standing behind that figure, while following the black woman, here as elsewhere, in a relation of historical posteriority. For as Toni Morrison remarked in a conversation with cultural critic Paul Gilroy published in 1993:

From a woman’s point of view, in terms of confronting the problems of where the world is now, black women had to deal with « post-modern » problems in the nineteenth century and earlier. These things had to be addressed by black people a long time ago. Certain kinds of dissolution, the loss of and the need to reconstruct certain kinds of stability. Certain kinds of madness, deliberately going mad… « in order not to lose your mind. » These strategies for survival made the truly modern person. 7

As the target of both skin and sex attacks, a cipher of negation twice over, the black woman in Morrison’s words and in Simpson’s photographs foresees the ravages of modernity—the loss of a symbolic matrix, the alienating effects of capital, the shattering of the subject—that have only escalated in her precipitous wake. 8 This figure’s « guarded conditions, » then, are very much our own, whether in the « post-modern » terms of 1989 or the « postblack » ones of 2005. It is just a matter of time before we are each called on to assume her position. 9

Two. This is what the artist looks like. She is thirty years old, featured on the front page of the arts section of a daily newspaper, standing warily before 1989’s Untitled (Prefer, Refuse, Decide).The date is September. We can make out the grain, the millions of little dots that constitute Simpson, her work, and the space they occupy. The data offered up by the dot matrix, however, is more or less superfluous, 10 since it is the caption that tells us everything we need to know, that the artist figured here is at the center of things precisely because of her relegation to the margins, and according to its author, Amei Wallach, there is no better place to be in the fall of 1990: “This year, outsiders are in… And lots of museums, galleries, magazines and collectors are standing in line to seize the moment with artists whose skin colors, languages, national origins, sexual preferences or strident messages have kept them out of the mainstream. Say it’s about time, blame it on guilt, call it a certificate of altruism for the living-room wall. Whatever, Lorna Simpson fits the bill.” 11 Indeed, she did: the first black woman ever to be chosen for the Venice Biennale; the subject of a segment on the PBS/BBC arts program Edge; and at the time, one of a handful of African-American artists able to parlay exposure at institutions like the Jamaica Arts Center in Queens into inclusion at a mainstream gallery in Soho. 12 Simpson’s fortuitous rise was taken to augur the beginning of the end of white patriarchal exclusion, the absolute other now given her « place in the sun »: representation in the age of representativeness. 13

Lorna Simpson, Three Seated Figures, 1989. Three color Polaroïd prints, five engraved plastic plaques. 30 x 97 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

Of course, such representation is never without its price, and as the mascot for a brand of specious multiculturalism, Simpson was expected to speak tirelessly of and for her oppressed sisters, and in the idiom that had already become her signature. Wallach, taking her cue from pieces such as Three Seated Figures of 1989 and Twenty Questions (A Sampler) of 1986, thus concludes that Simpson’s art is « about what a tangled and terrifying thing it is to be a black woman. But her methods come straight out of the mainstream, museum-accredited white art world.” 14 This pronouncement, while rather baldly put, is entirely symptomatic in its emphasis on the perceived tension in Simpson’s work between form and content, what Art in America critic Eleanor Heartney identified one year earlier as « hot subject matter » approached with « apparent detachment.” 15 Here is how she concluded a review of Simpson’s first exhibition at Josh Baer: « Drained of surface passion and tending toward an elegantly minimalistic style, [her] art sometimes runs the risk of being too understated… But when her anger and pain boil just below the surface, [her] restraint serves to magnify the intensity of her message.” 16

Lorna Simpson, Twenty Questions (A Sampler), 1986. Four gelatin silver prints mounted on Plexiglas, six engraved plastic plaques. Each print 24 in. diam. Collection Salon 94, New York. © Lorna Simpson

What these and myriad other voices attest to is a critical tendency at once more blatant and more insidious than the overdetermined image association that characterizes even object-oriented analyses of Simpson’s practice. More blatant, because no bones are made about conflating one work with another, and all of them with their maker, whose representative status elicits a well-worn caricature of the black subject: enraged by her victimization, frustrated by her corporeal and political lack, yet still willing to commodify her people’s suffering for the mortified pleasure of white audiences. More insidious, I think, is how such assessments applaud the artist’s efforts as successful exercises in self-discipline: the screaming horror of black female being reined in and made palatable by the Minimalist grid, its sublimatory force just enough to make black life over into the stuff of high art.

In these accounts, it is as if those two terms were by definition disjunctive, the very notion of « African-American art » somehow oxymoronic. Say it’s a « negative scene of instruction, » blame it on « art world racism,” 17or call it the « quiet confrontation » school of criticism, to repurpose an epithet used to describe the work of Simpson, Glenn Ligon, or any number of black artists, their visual tactics considered merely up-to-the-minute « white methods » for the expression of an ever-static “black experience.” 18 The funny thing is that as the art establishment discursively reproduced the sorts of ossification that Simpson’s art put under pressure, numerous critics simultaneously claimed her as part of a dramatic shift within African-American cultural production, one occasioned by « the end of the innocent notion of the essential black subject » and doubtless spurred on by recent conceptualizations of the hybrid one. 19 In fact, relatively early on she was counted among the ranks of a « postnationalist, » « postliberated » cadre of practitioners able to navigate seamlessly between « black » and « white » worlds: a generation whose emergence Village Voice critic Greg Tate had announced back in 1986, and in terms that both revise and anticipate other media-savvy ploys aimed at putting blackness squarely in the center of things:

These are artists for whom black consciousness and artistic freedom are not mutually exclusive but complementary, for whom « black culture » signifies a multicultural tradition of expressive practices; they feel secure enough about black culture to claim art produced by nonblacks as part of their inheritance. No anxiety of influence here—these folks believe the cultural gene pool is for skinny-dipping. Yet though their work challenges both cult[ural]-nat[ionalist]s and snotty whites, don’t expect to find them in Ebony or Artforum any time soon. Things ain’t hardly got that loose yet. 20

Lorna Simpson, Easy fo Who to Say, 1989. Five color Polaroïd prints, ten engraved plastic plaques. 31 x 115 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

Three. A, E, I, O, U. The second edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language defines a vowel as « a speech sound uttered with voice or whisper and characterized by the resonance form of the vocal cavities, » its enunciation requiring a postural opening of the body that is countered in Simpson’s Easy for Who to Say by the image of the vowel, which effects a figural closure. Though the letters concealing the model’s face intimate a multiplicity of subject positions she might occupy—adulterer, engineer, ingenue, optimist, unflinching—such musings are cut short by the matching red words marching beneath the pictures. « Amnesia, Error, Indifference, Omission, Uncivil »: these would place her outside the realm of subjectivity altogether. Ironically, the « I » still claims pride of place here, bucking the chain of equivalences intrinsic to language in order to center the work and our attention on that most basic of self-assertions, now made by a « self » that is tenuously present at best.

In this work, the meaning of the letter, like the orientation of the subject, is understood as fundamentally unstable yet always susceptible to reifying impositions. Easy for Who to Say thus stages the difficulty of rendering the black female body—that site of invisibility and projection so firmly fixed within the American cultural imaginary—while also maintaining the haunting sense of absence that is constitutive of identity as such. As Judith Butler argues in a recent commentary on the work of theorist Ernesto Laclau, no particular identity can emerge without foreclosing others, thereby ensuring its partiality and underlining the inability of any specific content, whether race or gender, to fully constitute it. This « condition of necessary failure … not only pertains universally, but is the ‘empty and ineradicable place’ of universality itself.” 21

We might say, then, that Easy for Who to Say aims for a « restaging of the universal »: if the words limning the photographs point up the ways in which black women have historically been denied its coverage, then the effacement of the figure underscores that the identity of this black woman can never be entirely accounted for given the structural incompletion she shares with all subjects. In the process, Simpson performs an act of « cultural translation, » critiquing the racism and sexism of previous universalisms by contaminating them with the very identity on whose abjection they were predicated. 22

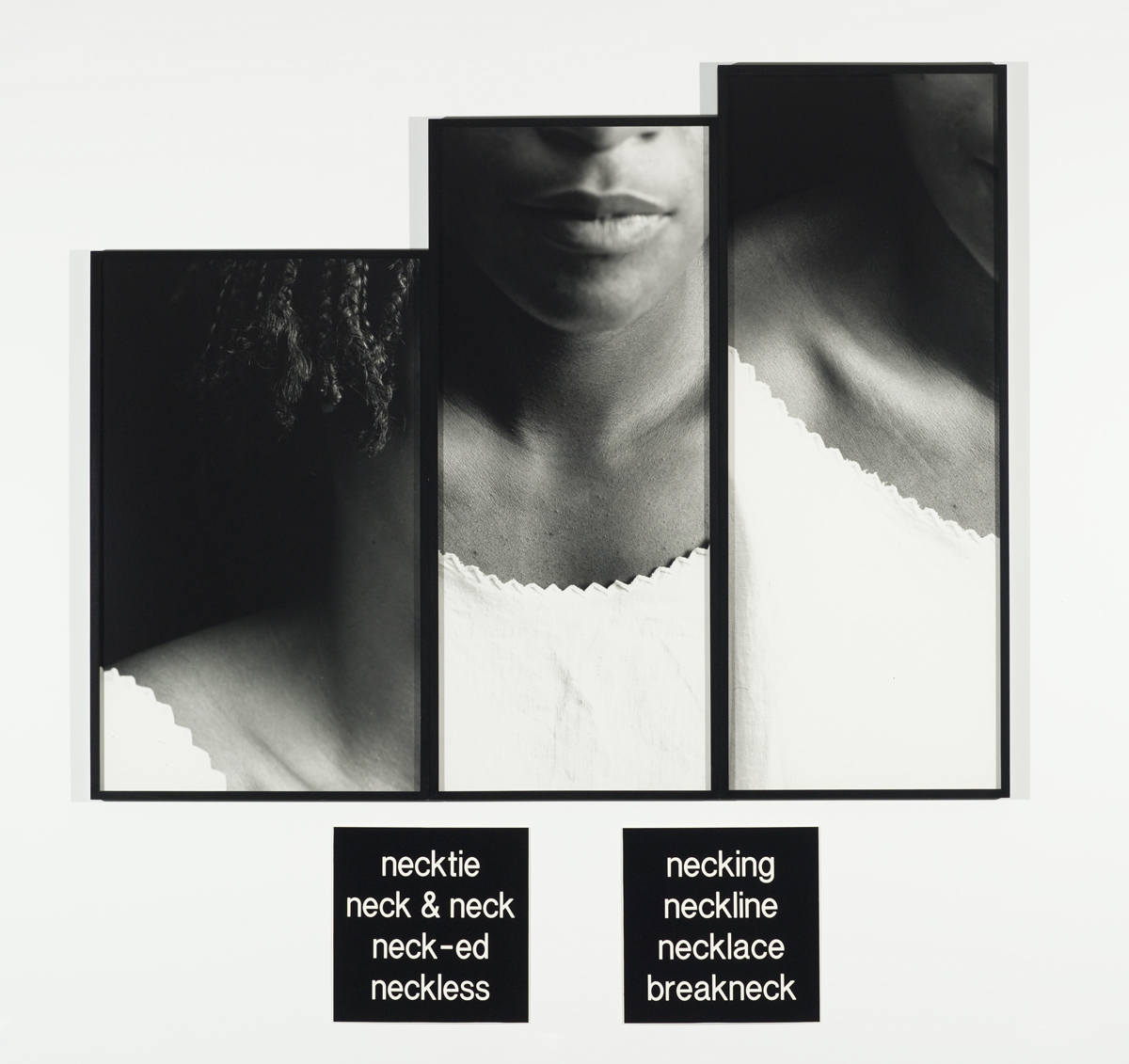

Lorna Simpson, Necklines, 1989. Three gelatin silver prints, two engraved plastic plaques. 68,5 x 70 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

In a 2002 reading of Necklines, critic Teka Selman suggested that such acts are at the core of the artist’s procedure, « help[ing] us to recognise that representation might not be a true representation of ‘the real’; instead it is truly a re-presentation or a translation of subjectivity, and in that translation, something is lost.” 23 And also gained. What we witness in Easy for Who to Say, as in Necklines, is a method whereby the peculiarities of one person’s body—in both cases that of Diane Allford, photographed in 1989—become the pattern on which the work is modeled: the fall of her braids and the tilt of her head determine the shape of a vowel, beautifully delineated collarbones draw us toward the neck. 24 One Diane after another, she sets the scale for the « black woman, » the « human, » her contours disrupted, and her subjectivity translated in order to speak of histories that are and are not her own.

Four. Sometime around the end of 1992, so the story goes, the figure slowly began to disappear from Simpson’s art. 25 Or, at least, its absence could be neither explained as a logical extension of her established themes, as was the case with 1990’s 1978-1988, nor dismissed as a negligible aberration from them, as evidenced by the critical vacuum that swallowed up an untitled gem of 1989. Suddenly adrift without the exegetical anchor of the black female body and now confronted with wishbones, candles, and all manner of increasingly sculptural synecdoches for its presence, several commentators explained Simpson’s apparent about-face through a reversal of the terms previously applied to her practice. On encountering the likes of 1993’s Stack of Diaries, critic David Pagel opined that the work was no longer about « sociological issues, » but « wide-ranging aesthetic » ones, that « seduction, » rather than « confrontation, » was its mode, and that Simpson now spoke in « whispers » instead of « declarations. » In the final analysis, Pagel found this new art considerably less effective, much « too bland and generic » when compared with the « biting energy of [her] earlier photographs.” 26

From top to bottom: — Lorna Simpson, 1978 – 1988, 1990. Four gelatin silver prints, thirteen engraved plastic plaques mounted onto Plexiglas. 49 x 70 in. — Lorna Simpson, Stack of Diaries, 1993. Photo-sensitive linen, steel, and etched glass. 81 x 28 x 18 in. — Lorna Simpson, Untitled, 1989. Two gelatin silver prints, two engraved plastic plaques. 30 x 16 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

Curator Thelma Golden, doubtless aware of how such readings could easily mutate into backlash, took the completion of the multipart video installation Standing in the Water as an occasion to air her own views on this unexpected turn of events and, ultimately, to put the question on everyone’s mind to the artist herself. « The figure, your colored, gendered figure, seems to have moved out of the work. Our colleague Kellie Jones, our homegirl, art historian, and curator, and I have only half jokingly referred to this shift by titling the new piece ‘Bye, Bye Black Girl…’ 27 But I think I understand this shift…. By denying viewers a figure are you disallowing them a place to ‘site’ the issues so specifically, as you have similarly denied access to a face in the past?” 28

Lorna Simpson, Standing in the Water, 1994. Three serigraphs on felt panels, each 60 x 144 in., two video monitors, each 2 x 4 in., ten etched glass panels, each 12 x 12 in., sound. Overall dimensions variable. Installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris, New York.

Simpson’s reply? « Not really…. I am just trying to work through these issues without an image of a figure. My interest in the body remains. The text in this piece refers to both political and personal concerns.” 29 Among the concerns enumerated in the lines scrolling down the work’s two small monitors over suitably aquatic images, were the plight of enslaved Africans who jumped ship, « the promise of showers » held out to Jews on their way to the camps, and the memory of the artist’s « first time pissing in the ocean. » Anticipating, and in a sense perceptually priming the spectator for such evocations, were a sound track of water effects and three five-by-twelve-foot lengths of felt printed with pictures of the sea. These were surmounted by glass squares, each featuring the same photograph of a pair of shoes, yet etched differently to mimic varying degrees of submersion. 30 By January of 1994, when Standing in the Water opened at the Whitney Museum at Philip Morris in New York, these were the sole traces of the body that had guided Simpson’s art and would continue to haunt it.

As hardly needs saying, Golden and Jones’s collegial quip was hardly emblematic of the larger critical reaction that greeted Simpson’s retreat from and of the figure, though by 1995, with greater distance from the salad days of multiculturalism, commentators on her latest body of work, the Public Sex series, could now speak to visual and historical nuances that had previously escaped them.

Lorna Simpson, The Park, 1995. Serigraph on six felt panels. 67 x 68 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson

Indeed, again printed on felt, and as usual paired with text, these gridded serigraphs seemed to invite such scrutiny, their panoramic scale calling up cinematic narratives, their lustily rendered surfaces rhyming with the clandestine activities they hinted at only to occlude. Heartney, for one, welcomed this departure, seeing pieces like The Park as grandly metaphorical in tone and broadly inclusive in address: « Race, previously one of Simpson’s dominant themes, is played down here … [and] the works evoke a more universal sense of melancholy.” 31 Most critics, however, were markedly less sympathetic, suggesting, as did Robert Mahoney, that « Simpson once again toys with gaps in the way we assign meaning to hot topics, but the idea has been attenuated by her dull-is beautiful approach.” 32

What is most instructive, if perplexing, about these responses is that the banishment of the figure seemed to compel a sharp bifurcation of Simpson’s critical project: one either lauded her « new-found » interest in the universal or judged the work deficient without the discursive meat of identity politics. Yet if anything, I would counter, her practice has consistently worried over the status of the body and the consequences of its divergent modes of self-perception for the constitution of the black female subject. As theorist Kaja Silverman argues in The Threshold of the Visible World, each of us comes to apprehend ourself as a self not only through the jubilant encounter with our own reflected image that Jacques Lacan famously recounts in « The Mirror Stage » but also, as psychoanalyst Henri Wallon maintains, through the sum of our physical contacts with the world, resulting in an apposite bodily identity that is keyed to tactile, cutaneous, and erotogenic sensation. Silverman terms these two schemas the visual imago and the sensational ego, respectively, and though they are always initially disjunctive, their later disalignment « does not seem to produce pathological effects.” 33 It is tempting, then, to reinforce the apparent fissure in Simpson’s art in the language Silverman provides, supposing that, say, Guarded Conditions, in its ruthlessly frontal presentation of the bodily image, dwells on the first register, and that The Bathroom, a 1998 addition to the Public Sex series, occupies the second.

Lorna Simpson, The Bathroom, 1998. Serigraph on four felt panels with one felt text panel. 52,5 x 52,5 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson.

To do so, I think, would be to miss the point, since it is the troubled coexistence of these modes that is at issue in Simpson’s art, the one continually qualifying, undermining, and preying on the other. Listen to how she slyly captions the later work: « There were five stalls. In the second stall there were three legs. » Those intertwined bodies only revealed themselves to the narrator as an odd three-legged, two-backed beast, necessitating the translation of appearance into the grammar of bodily relations, though even this account affords little descriptive pull with the image itself, which metastasizes the rift between vision and touch in the elaboration of subjective experience. Here, the proliferation of light-catching surfaces—of mirrors, tiles, and doors—engenders a volley of reflections thrown into doubt by the intransigent blur of the very material on which they are printed: we are left in The Bathroom with felt and fantasy after the photographic fact. Now look again to Guarded Conditions, to the model’s shifting contact with herself; her registration of postural integrity, of corporeal « ownness, » is at odds with the disarticulation of her image perpetrated by the grid: there, too, we encounter the remnants of a scene accessible to our gaze and subject to our projection, but incapable of telling us more than half the story.

Lorna Simpson, The Bed, 1995. Serigraph on four felt panels with one felt text panel. 72 x 45 in. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Lorna Simpson.

Two sides of the same coin, these works emphasize the slipperiness of our grasp on the world by holding open the perceptual gap that some inevitably navigate with greater ease than others. As Silverman reminds us, and as Frantz Fanon teaches us, it is the specular malediction of the black subject 34 not only to recognize this disjuncture but also in a certain sense to inhabit it in order to preserve the bodily ego from the deidealizing images of blackness that litter the cultural landscape and cling to black skin. « I am given no chance, » he tells us. « I am overdetermined from without. I am the slave not of the ‘idea’ that others have of me but of my own appearance.” 35 In the text lying alongside The Bed, in language as politely arch as it is « brilliantly annoyed,” 36 Simpson tells us what it means on one evening, at one hotel, to be so « overdetermined from without, » marking how the syntaxes of color, class, and privilege at once disrupt and define what we know to be properly ourselves. « It is late, decided to have a quick nightcap at the hotel having checked in earlier that morning. Hotel security is curious and knocks on the door to inquire as to what’s going on, given our surroundings we suspect that maybe we have broken ‘the too many dark people in the room code.’ More privacy is attained depending on what floor you are on, if you are in the penthouse suite you could be pretty much assured of your privacy, if you were on the 6th or 10th floor there would be a knock on the door. » Contrary to the critics, it is this disembodied voice, alive to the rhetoric of appearance, attuned to the actualities of desire, and everywhere evident in the Public Sex series, that returns to entice us, asserting the presence of one black woman who remains even as her figure is ghosted away.

Kiki Smith, Pee Body, 1992. Wax and glass beads. 27 x 28 x 28 in. Installation dimensions variable. © Kiki Smith, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photograph courtesy Pace Gallery

Five. « The thing I think I have the most difficulty with … is the thing about the black figure … how much ‘politicized’ space this figure takes up. For instance, Kiki Smith does works about the body; she can do a sculpture out of resin or glass, it’s kind of this pinkish Caucasianish tone, and her work is interpreted as speaking universally about the body. Now when I do it I am speaking about the black body…. But at the same time, this is a universal figure …” 37

What I have been trying to get at over the course of these « mannered observations » 38 is simply this: that despite its implicit deconstruction of the particular and the universal, the visual and the sensate—those notions so central to the claims of any aesthetic enterprise—Simpson’s work often found itself policed by them, outpaced by a racial specter that would empty the subject of all content save for that projected on its surface. Until, that is, the black female body became as phantasmic in her art as it was effectively imagined in the discourse that preceded it. That art—recursive, repetitive, and apace with its own historicity—thus pinpoints a posture of belatedness that has consistently animated the « changing same » of African-American culture, because as Guarded Conditions makes clear, it is ever our lot to be captured in the darkling wake that renders the black subject, now as then, irremediably « postblack. » 39 We can only apprehend the complexities of Simpson’s oeuvre, I want to argue, its relation to the « political, » its strategic lapses and capitulations, by coming to grips with the imbrication of « black » and « white, » that infernal pairing, which not only forms the ground on which « African-American art » is predicated but also deforms the meaning of modernity itself. Of course, as no one needs reminding, things ain’t hardly got that loose yet.

Huey Copeland, 2005 [revised 2013]

Homepage : Lorna Simpson, Untitled (Prefer, Refuse, Decide), 1989. Courtesy the artist & Sean Kelly Gallery, New York. © Lorna Simpson

This paper derives from a talk delivered at the 2004 College Art Association annual conference. That talk, my initial stab at thinking about Simpson’s practice, was part of a panel organized by Darby English, entitled « Representation after representativeness: Problems in ‘African-American’ Art Now. » Thanks go, then, to English for including me in that conversation, as well as to Naomi Beckwith, Gareth James, Glenn Ligon, Eve Meltzer, and Alexandra Schwartz for their incisive comments on earlier drafts of this text, which could not have been realized in its present incarnation without the tireless (and cheerful) assistance of Amy Gotzler at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York. My research was also importantly aided by ACLS Fellowship support with funding from the Henry Luce Foundation. Above all, thanks to Lorna Simpson for her generosity, encouragement, and continually challenging example. My first book, which revisits and expands his thinking on Simpson among others, is Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America, forthcoming October 2013 from the University of Chicago Press.

Huey Copeland (Ph.D., History of Art, University of California, Berkeley, 2006) is Director of Graduate Studies and Associate Professor in the Department of Art History at Northwestern University (Evanston, IL, USA), with affiliations in the Department of African American Studies and the Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies. His work focuses on modern and contemporary art with emphases on the articulation of blackness in the American visual field and the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality in Western aesthetic practice broadly construed. A regular contributor to Artforum, Copeland has also published in Art Journal, Callaloo, Parkett, Qui Parle, Representations, and Small Axe as well as in numerous edited volumes and international exhibition catalogues, including the award-winning Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art.

References