Teresa Grandes (who is co-curating this exhibition with me) and I went to Turin to see the works. More comfortable moving among the artist’s circuits than those of the gallerists and collectors, I let myself be guided through the twists and turns of the sinuous territories of the commercial art world by the experience and know-how of Teresa Grandes. We have already seen hundreds of reproduced images of Carol Rama’s work but we’ve never seen them face to face. Furthermore, Carol Rama is still alive: born in 1918 she is approaching a hundred.

Everyone has warned us about the difficulties and challenges posed by getting access to Carol Rama’s work. We arrive in Turin as two curators dressed up as tourists. Our contact in Turin is Cristina Mundici, who has organised and curated many of Carol’s exhibitions and is now running the Carol Rama archive with a group of experts and friends. Cristina opened the rest of the doors for us, taking us to see all of the collectors. In four days we saw more than 300 works many of which continue to be unknown after years shut away in garages and basements.

Our hotel in Turin, whose only selling point was perhaps its modest price (European austerity has meant that the museum makes us travel like two candidates of the Peking Express), ends up being right in the middle of the Carol Rama constellation. Cristina Mundici lives just opposite the hotel. Going down from Principe Amedeo, where the hotel is based, towards the Piazza Vittorio Venetto until the Po river, leaving behind the Mole and the museum of cinema in the background, we arrive at the building where Carol Rama lived for the majority of her life on Via Napione. While we kill time making sure that we don’t arrive too early for our meeting, we find out that the apartment of the architect and friend of Carol, Carlo Mollino, is also on the same street next to the river.

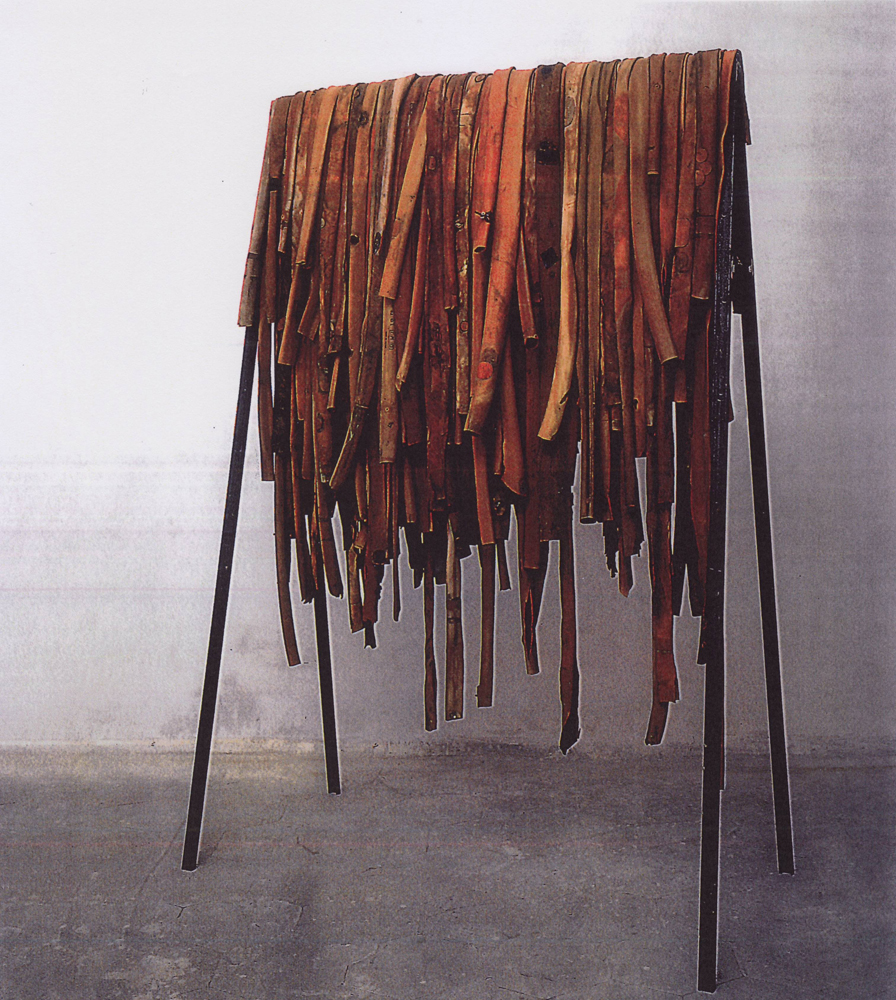

The first thing that surprises us about entering what was Carol Rama’s studio for 70 years, is the darkness: all the windows in the apartment have been blinded with thick black curtains. Just as Caravaggio, Man Ray or Dan Flavin worked with light, we could say that Carol Rama worked not only in but also with darkness. The feeling is more haptic than visual: it was as if we had fallen into Meret Oppenheim’s furry cup of Le Déjeuner en Fourrure (1936). It wasn’t about seeing, but rather touching, sensing. As we moved through this dense blackness we saw progressively more and more yellowing sepia photos; hundreds of images of Carol Rama who transforms herself throughout them as an actress directed by time. Passing over them stage by stage we find a shoemaker’s anvil, dozens of wooden moulds, her own works and those of Man Ray, Picasso and Warhol, an African ritual mask, collections of taxidermy eyes, fingernails and hair, dozens of bicycles tyres (a recurring element of her works made after 1970) hanging flaccidly from hooks and piles of old soap that have degraded over time appearing now as slabs of animal fat. Her apartment is like an organic archive of her own work in the process of decomposition.

The work of Carol Rama is a mine that has laid dormant underground, hidden under the shiny surface of modern art. Encountering just one of her works can implode all of the grand art historiographies. Not only the dominant histories but also those of feminisms. Carol Rama was a contemporary to and in dialogue with (sometimes in person and other times through her work) everything and everyone: Picasso, Duchamp, Luis Brunel, Man Ray, Jean Dubuffet, Orson Wells, Warhol, Sanguinetti, la Ciccoline and Jeff Koons….but she is an invisible contemporary.

Carol Rama’s name doesn’t appear in any history of art. Not even in those which, due to some epistemological and political mishap, have been called the histories of “women artists”. The Italian critic Lea Vergine rescued her for the first time from this historiographic erasure when she included her in the 1980 exhibition “L’Altra Meta dell’ Avanguardia/The Other Half of the Avante-Guarde: 1910-1940”. Vergine is the first person to understand Rama. But this gesture wasn’t enough to make Rama’s unclassifiable work enter into the established international museum circuit. Apart from a few exhibitions in the 90’s (at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, which also travelled to Boston), the brief public acknowledgment of her work marked by the 2003 Venice’ Golden Lion and the distribution labour done by gallerist Isabella Bertolozzi, for the most part Carol Rama’s work still sleeps in the basements of Italian collectors. And yet as traces of seven decades of art production, her body of work shifts how we understand avant-garde movements. Carol Rama invented sensurrealism, visceral-concrete art, brut porn, organic abstraction… and more and more.

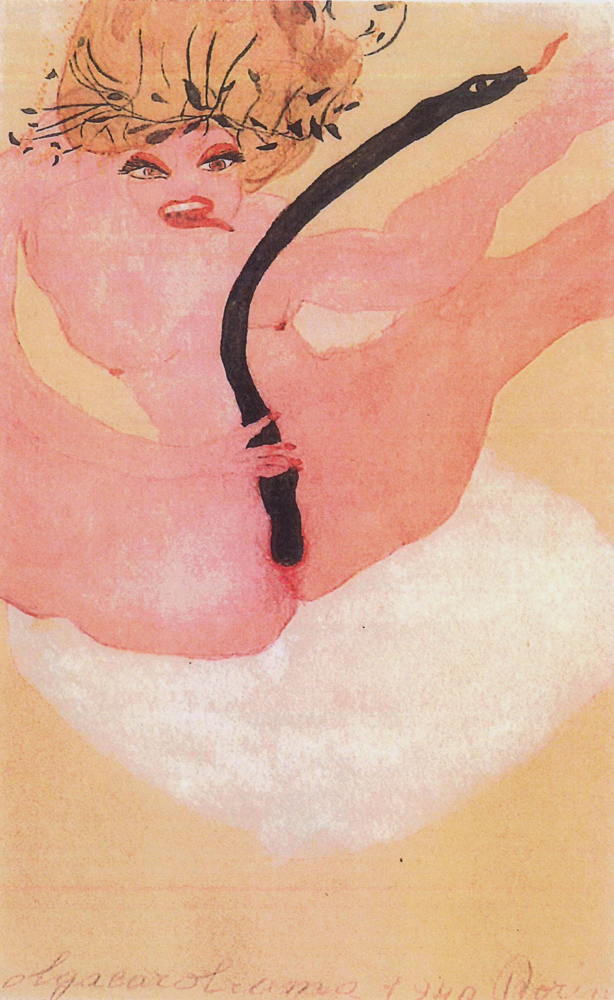

A history-fiction might propose that her works produced between 1936 and 1940 were made with the intention of being seen in 2014. The way in which Carol Rama represents the body and sexuality could be compared with a sort of Piero de la Francesca who would have painted “The ideal city” in the context of a society that didn’t recognize, or rather rejected, the notion of perspective. A woman shitting, a penetrated by a human penis, a body who opens up a vulva with two hands, a snake sliding out of an anus….The images that Carol Rama produced surpass the frames of the sexual intelligibility of modernity. And yet how are we to understand the works of Kara Walker, Sue Williams, Kiki Smith, Elly Stik, Marlene Dumas and Zoe Leonard without them?

Among other things, Carol Rama anticipates the transformations of the representation of the body and sexuality that will take place over the last three decades of the twentieth century. In the watercolors of her early work, Carol Rama invents a figure that, despite having never appeared in the grand catalogues nor entered the exhibition halls of MOMA, is one of the most iconic images of the 20th century: a body whose head is crowned with thorns that gradually become a small garden of yellow flowers. In the series Appassionata (1940), a body, naked apart from the shoes, appears lying on a bed strewn and hung with a web of restraining straps. In the background floats a structure that emerges from the crossing and interweaving of the bed frames and the straps. It could be said that this structure is the consequence of the schematic application of some of the visible laws of cubism but that Carol Rama has modified with the extra variable of “affect.” We could call it, following Deleuze, Affection-Cubism. Art is the result of the extraction of the image from its space-time co-ordinates in order to transform it into percepts and affects. The floating structure is at the same time madness and the incarcerating system of the subject, a possible man of unconscious and of its relationship to the disciplinary apparatus.

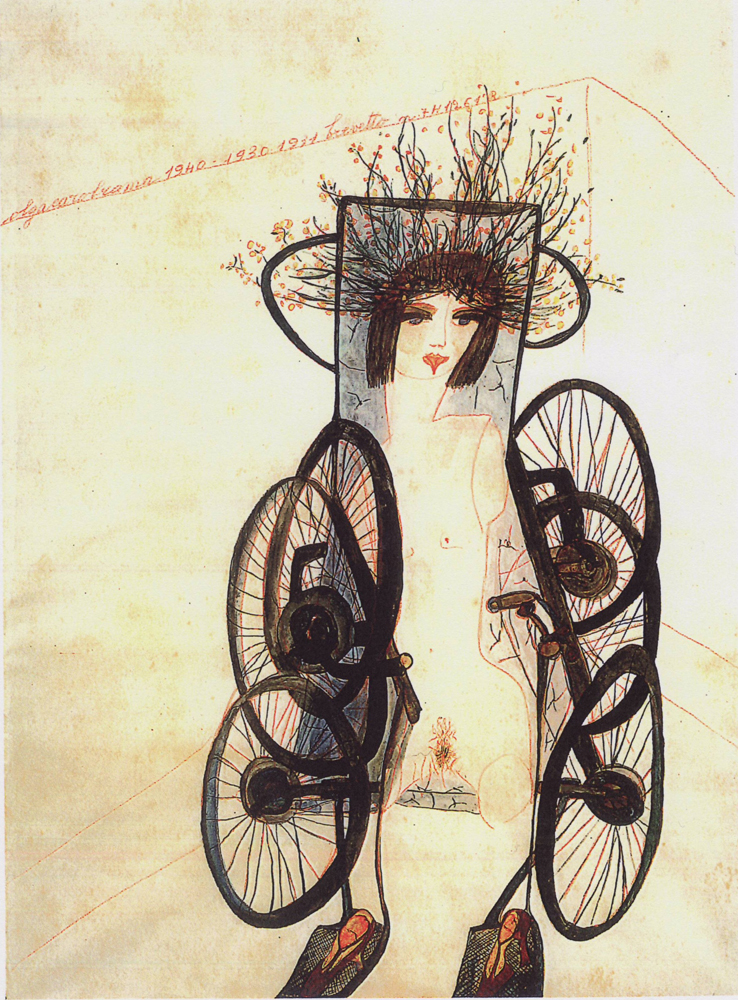

The representation of the body that Carol Rama would construct by the end of the 30’s is comparable in poetic intensity and acuity only to what Antonin Artaud would also be working on throughout the same period. In another one of the watercolours, the body, now with its arms and legs amputated, appears naked and fallen on a vertical plane with wheels. Here, as with the floating bed structure, the space-time of the wheels suffers a distortion as if it were observed from a multiplicity of viewpoints. However this multiplicity of perspectives doesn’t necessarily produce a sense of movement (as would have been the case with Muybridge or Boccioni), but, on the contrary, it forces the body to incorporate the inorganic: the wheels and footrests become prosthetic limbs. In the centre of the image the chromatic vivacity of the head-garden, the erect tongue and the vulva represented as an external organ and not as a orifice stands out against the subdued colour of the body. This body should be dead, but its not, it’s alive.

How did Carol Rama make these watercolors at only 18 years old? All the biographical summaries about Carol Rama mention the same event that is presented as foundational: her father, an industrial manufacturer of bicycles, went bankrupt and committed suicide when Carol was 22. Speaking with her friends, gallerists and collectors, however, there emerges a different story. Her father was homosexual and lived a double life. The dishonour brought about by being homosexual in the Turinian bourgeoisie in the 40’s was much worse than financial ruin. After the suicide, the mother ended up in a psychiatric hospital. But this story can’t answer these questions: Who is this amputated body? Who is looking at it? Where does this sexual desire come from?

In her apartment, after visiting her studio we approach her bedroom. The skin of Carol Rama is almost transparent and her white hands are the only soure of light in the otherwise opaque room. I get closer to her. Teresa is a little more discreet, waiting just by the door. I’m like an insect seeking out answers to my questions. But there won’t be any. Since 2005 Carol Rama has begun a terminal process of loosing consciousness.

It seems inconceivable to be curating the first big retrospective of the work of an artist who has been nearly entirely forgotten by the history of art, who herself is in the process of loosing her memory. The history of art is the history of our own amnesia, the forgetting of all that we don’t want to look at, of that which resists being absorbed by our hegemonic frames of representation.

I ask myself if this exhibition could be a form of reconstructing or inventing her memory or, alternatively, if our attempt will simply form part of the general amnesiac process that Walter Benjamin called progress. I ask myself if our act will be tautological or oppositional. If we are just another stage of this collective Alzheimers or if we could open a line of flight, undo forgetting, invent another archive.