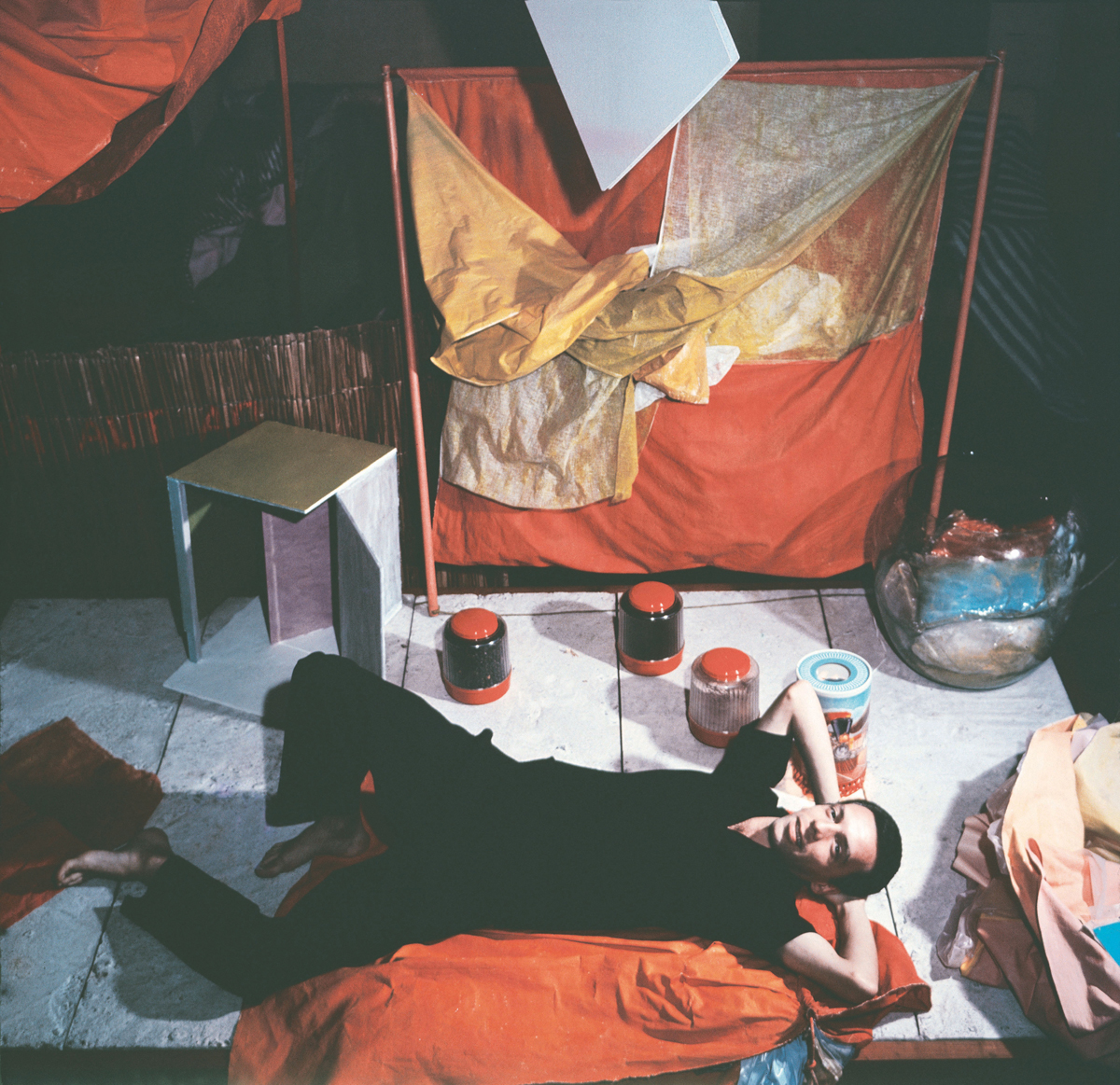

Hélio Oiticica with Bólides and Parangolés at his studio, Engenheiro Alfredo Duarte Street, Rio de Janeiro, ca. 1965. Photo: © Projeto Hélio Oiticica.

The Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main (MMK) is presenting the biggest European retrospective exhibition of the work of the Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica, running until the 12th January 2014. You will know Oiticica, perhaps without realising, because in 1968 Caetano Veloso used the title of one of his artworks for a music album which would make it world famous: Tropicalia. Oiticica’s Tropicalia was an installation inspired by the favelas of Brazil, with it’s own beach hut, sand, real plants and living parrots. Every contemporary art museum wants to have its own Tropicalia now, and yet the work of Oiticica, more metabolic than object based, more affective than retinal, is still to be discovered.

I am not interested in Oiticica’s parrots (now swooning absurdly under the artificial light of the museum) or in the Tropicalia cool revival in the world of fashion. I’m interested in Oiticica as a figure that condenses and anticipates the becoming of the 21st century artist: migrant, precarious, intern, temporary artist in resident, pansexual, visionary, vulnerable, sick, prematurely dead. Cognitive bio-political worker.

In 1971 Oiticica, 35 years old, would travel from Brazil to New York with a Guggenheim grant for artists. Before arriving in New York, Oiticica had already developed an immense and incredibly innovative body of work that would herald the paradigm shift that would transform future curators and cultural managers —who at this time were still disconnected from the kinds of social and political practices that enriched the work of Oiticica. His work anticipated the move from work to relation, from the individual to the interpersonal, from visual reception to a multi-sensory experience, from object to subject and from art as sort of clinical diagnosis to art as universal shamanism.

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolés, 1965-1979. Installation view, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Axel Schneider © MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst.

Before arriving in New York, Oiticica had already elaborated not only his Tropicalia but also the notion of “environmental art” and “metaphysical colours”, the “Bolides” (mouldable structures that could be manipulated by the public) and the “Parangoles” (pieces of material that served as improvised outfits for starting a social ritual of dance and creation)… His arrival in New York and the securing of the Guggenheim grant do not serve as ‘recognition’ for Oiticica but rather as metamorphosis: just as Gregory transformed into an insect, Oiticica transforms into a migrant from the South without resources and wandering the streets of downtown Manhattan. When the grant finishes in 1972, Oiticica begins working odd jobs, including a trafficker of cocaine, pills and hash. Oiticica died in 1980 of a cardiac arrest.

It was during this period of bare survival in New York, in which the identity of the precarious migrant and drug dealer was threatening to devour the artist, when his artistic collaboration with Nelville D’Almeida occurred. They made a work together entitled Block-Experiment in Cosmococa: a combination of installations verging on the cinematic, the architectural and the performative which took place in Oiticica’s apartment on the Lower East Side. There is no visual documentation of the installations but Oiticica’s innovative texts that reconstruct the installations (protocals of the work, conversations, letters, reflections), could be found today in an anthology of the best literary experiments of the 20th Century.

Hélio Oiticica, Bloco-Experiências in Cosmococa – programa in progress, CC2 Onobject. Installation view, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst. Photo: Axel Schneider © MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst.

Each Block-Experiment in Cosmococa was an installation that assembled at least four elements: an interior design of the space that marked out the conditions of reception with a series of objects (hammocks, sofas, balloons…); the projection of a series of slides (popular images of cultural icons: Marilyn, Hendrix, ect.) onto the surfaces of the 6 sides of the room (including the ceiling and the floor); the design of a sound environment; and finally a performative protocol in which instructions are presented that immediately establish certain relations between vistor-participants and the work. A substance similar to cocaine (who knows if it was actually the real cocaine that Oiticica was trafficking to live off) appears in lines across the faces of Marilyn or Hendrix.

Once again Oiticica, like a clairvoyant or a lookout, points out the track that would follow: in the 1970’s the relations between the North and the South would be regulated and mediated by the production and trafficking of drugs. The United States were entirely tied up in Brazil, Paraguay, Peru, Chile, Columbia, Cuba… by huge lines of coke. In the “war against drugs” that Nixon declared in 1971, cocaine would become the “scapegoat” that would allow the US to acquire a moral advantage over its political adversaries. Used legally in many pharmacological compounds and trafficked illegally to the USA through trade routes from the Caribbean and South America, cocaine is in the 1970’s the prime object of mass consumption, as distributed as Warhol’s Campbell soup. The difference between Campbell soup and cocaine (a difference which also distinguishes the publicist work of Warhol and the shamanic rituals of Oiticica) is of course that the latter is a powerful technology for the modification of consciousness.

Oiticica was looking for a kind of artistic experience that could be “sniffed” like a line of cocaine. In the Cosmococas, Oiticica and Nelville use cocaine as a kind of cognitive “readymade”: they displace cocaine from the networks of trafficking and consumption and they integrate it into a system of signification in which it can function as a dispositive for producing dissident forms of subjectification.

Each Cosmococa is a multimedia texture that, Oiticica states, “functions as an open program for random operations” capable of enacting a series of tools for cognitive, corporeal and sensory de-habituation. Here Oiticica is investing in the organic materiality of processes of subjectification which art proposes and the possibility to create a bio-public: a living spectator whose metabolism is open to the mutation.