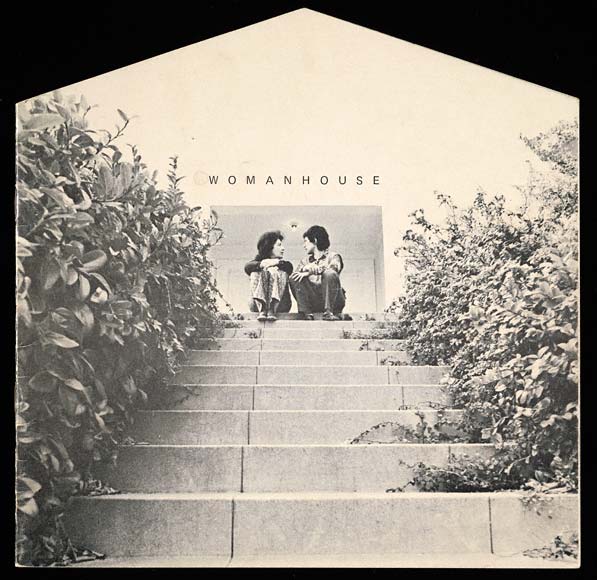

Cover of the Exhibition Catalogue Womanhouse (showing Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro). Design by Sheila de Bretteville. (Feminist Art Program, California Institute of the Arts, 1972). Photo © Donald Woodman. Courtesy of “Through the Flower” archive

In October the curatorial and activist collective a people is missing will republish and distribute a video documentary by Johanna Demetrakas entitled Womanhouse (1974, 47 min.) for this first time in France. I still remember when I first saw the documentary; an afternoon in New York in Laura Cottingham’s house. Laura had undertaken an expansive investigation about feminist artistic practices in North America in the 1970’s in order to make Not For Sale (1998), which is without doubt the best documentary about the theme to date. In her personal archive was the Demetrakas video. At the time I situated myself as queer, while Laura continued to position herself as a radical feminist. Watching the documentary about Womanhouse together, we reconciled each other and managed not to get trapped in the indeterminable debate between post-structural criticism and socialist feminism. After all we have the same history in common. On the pretext that she had a double copy of everything, Laura filled my backpack up with videos with the frenzy of a bootlegger or somebody who had been holding a message that had waited years to be told. Still inexpert, I went back to my apartment in Brooklyn and spent a week working through the videos (by Demetrakas, Martha Rosler, Ilene Segalove, Faith Ringgold, Adrian Piper, Ana Mendieta…and a copy of Not for Sale) as if they had been made only for me, taking notes that would constitute my first classes in gender and performance in the University of Paris VIII at the beginning of the year 2000. Feminist art in the 1970’s was neither a style nor a movement, but rather a set of heterogeneous operations of the denaturalization of the relations between sex, gender, visuality and power. The documentary Womanhouse changed my way of thinking about artistic practice and helped me to understand that it was possible to transform the university and the museum into spaces of sexual and political emancipation.

Ignored for years by the hegemonic narratives of art history, the project “Womanhouse” emerges today as an indispensable work for understanding artistic practices of the 1970’s as well as for rethinking the future of art pedagogies and the relationships between architecture, performance and social activism. The documentary invites us to approach the first feminist pedagogical project initiated at the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts) by Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro and a group of students at the beginning of the 1970’s. In the autumn of 1971, Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro inaugurated the Feminist Art Program. With the school under construction and a lack of space, Chicago and Shapiro took on an idea proposed by Paula Harper: rent a space and transform it into a feminist project. They found an abandoned house on a waiting list to be destroyed on Mariposa Street in a residential neighbourhood in Hollywood, Los Angeles. Despite the derelict state of the house, Judy Chicago decided that the “mariposa” (butterfly in Spanish; her lucky animal) was a good sign. During the following six weeks a group of 25 women would study, work and perform inside of the house, transforming each of the spaces and the 17 bedrooms into places of work and study. Demetrakas films the collective work sessions in Womanhouse and shows how the space transformed from a house to a place of exhibition between 30th of January and 28th of February in 1972. As if it were political allegory (or history’s bad joke), the first exhibition of feminist art would take place in an abandoned house: a domestic space about to be demolished, transformed first into a collaborative and environmental artwork and later into an ephemeral gallery.

In Womanhouse, it is domestic space itself, historically naturalized as “feminine”, that is transformed into an object of critique and artistic experimentation. The heterosexual home, a privatized and disciplinary site, is politicized and denaturalized through language, painting, installation and performance. This process of investigation began in 1969 at Fresno State College (now California State University) when, in response to the exclusion of women in the university and the circuits of production and display of art, Judy Chicago began to distance herself from abstract art and organized the first course of “art and feminism” outside of the art school building. In the “Kitchen Consciousness Group”, Judy Chicago and her colleague Kathie Sarachild put in motion an experimental method of collective learning through speech and through the dramatization of exclusion. Language displaces painting and performance takes the place once held by sculpture in traditional art training. Chicago groundbreaking idea was that art could transform consciousness and therefore become also a tool of political emancipation. On the other hand, empowerment techniques and consciousness-raising sessions became tools to produce art. Breaking the hierarchy of teacher-student, the participants constructed collective autobiographical narrations of their political experiences of being artists and women. Rape, discrimination, abortion, maternity, lesbianism, masturbation, divorce, contraception… appear now as spaces of not only political but artistic intervention. In a process of dematerialisation of art and intensification of critical practice, learning in the context of artistic practice shifts from forms of material production towards an art understood as a process of cognitive and somatic emancipation.

The aim of art is no longer to produce an “object” but rather to invent an apparatus of re-subjectification that is capable of producing a “subject”: another conscience, another body.

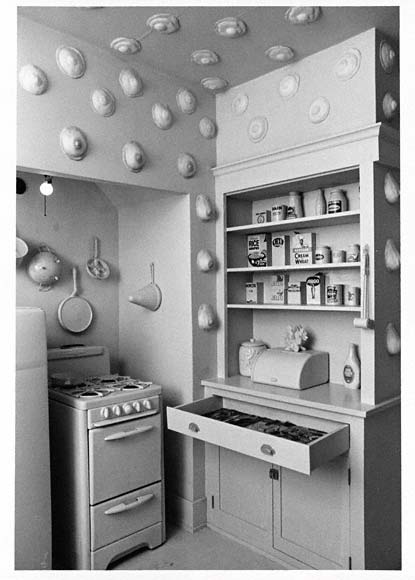

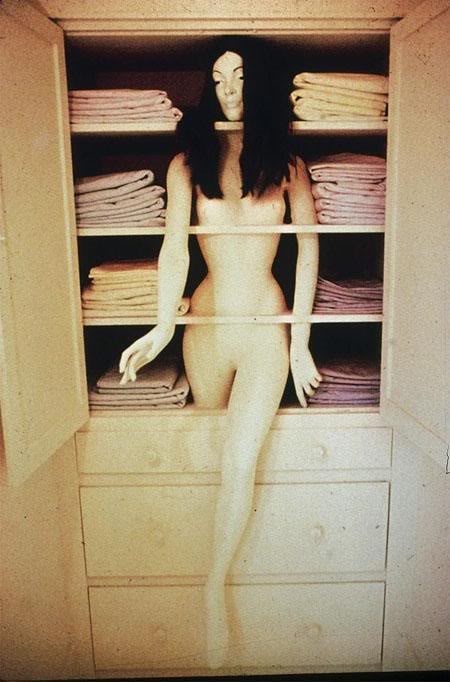

It is both motivating and moving today to revisit the interior of Womanhouse through Demetrakas’ documentary: to attend the conscious-raising conversations, to enter into the kitchen transformed by Vicki Hodgetts into an entirely pink space in which fried eggs invade the walls as breasts, or Judy Chicago’s “Menstruation Bathroom” which was full of red tampons that would later be unfairly denounced as a cliché of feminist art (Chicago’s was just underlying the power of new biopolitical and hygienic techniques over the body), or to see the linen closet transformed into the body of a woman by Sandy Orgel, or watch Chris Rush performing the work “Scrubbing” in which she performs the act of cleaning the floor in real time before an audience as uncomfortable as they are surprised, or Faith Wilding (today known internationally for her cyberfeminist work) in her performance “Waiting” in which she narrates female existence as an indeterminate process of moments of waiting, or again Faith Wilding and Janice Lester dressed up as a penis and vagina performing Judy Chicago’s “Cock and Cunt Play”.

Screenshot of Womanhouse by Johanna Demetrakas (1974). Faith Wilding and Janice Lester, The Cock and Cunt Play, performance. “Womanhouse” Project, 1972

Womanhouse produced a critical intervention of denaturalization that also brought into focus the interrelations between 4 supposedly distinct institutions: the university, the museum, the domestic space and the body. Womanhouse posed a critique of domestic space as a technology of production and domination of the feminine body while highlighting the institution of marriage and sex as a regime of enclosement and discipline. The displacement of these first feminist art pedagogies to domestic space (to Judy Chicago’s kitchen and to Womanhouse), which were located outside of the university and museum, is a sign of the epistemological limits of educational institutions of the 1970’s. Feminist critique put in question the architectures of knowledge and its epistemological frontiers. It is possible now to understand Womanhouse as part of the work of Institutional Critique that other artists (Michael Asher, Robert Smithson, Daniel Buren, Hans Haake, Marcel Broodthaers…) were carrying out at the same time, and yet they extended the critique further: to the institution of domesticity and its relations with art education and the museum.

Institutional contempt directed towards the artistic practices and criticisms of feminism would cause the forgetting and even the total destruction of the archive of feminist art from the 70’s: the house in which the Womanhouse experiment took place, the installations, the murals, the architectural transformations, were all destroyed during Roland Reagan’s government. However, the images captured by Demetrakas return to us today, to put it in the words of Georges Didi-Huberman and Warburg, as a kind of ‘ghost’ or ‘survivor’ so that it is still possible to dream our own history and imagine other possible mutations of the institutions of the school and museum.

Curatorial and activist collective a people is missing

Womanhouse, a film by Johanna Demetrakas (1974 VOSTF)