At the same time as I try to write a political history of the organs (not as quickly as I would like incidentally) I have also been trying to curate an exhibition of Carol Rama’s work, commissioned by the director of Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (MACBA), Bartomeu Marí, which will open in 2014. Although I’ve been working in the context of the museum for over ten years now, my relationship with the format of the exhibition has always been distant. The museum, more than the university, has been an apt place for rethinking the relationship between languages, the representations of sexuality, of gender, of the body and the politics of resistance to processes of normalisation. As an experiment in public micro-spheres, the museum puts in dialogue artistic practices, the processing power of social movements and the critical innovations of the humanities. It’s a place in which counter-fictions are invented; a place where techniques of dissident subjectivities can be tested. At MACBA or the Reina Sofia, I have always privileged the invention of dispositifs of production of discourse and critical visibility over the exhibition format as they seem to allow for a large amount of experimentation and direct action. The Postporn Marathon, which I organised in 2003 at MACBA under the direction of Manolo Borja and with the support of Jorge Ribalta, could have been an exhibition but what I felt was necessary was to transform it into an investigatory meeting, a place for debate, live experimentation and performative production. The important thing was to create networks of collaboration, invent other languages and alternative practices.

When your work concerns political minorities (feminisms, dissident sexual and gender movements, anti-colonial movements…) there is a danger with the model of the exhibition (the list of examples from the last couple of years would be long and embarrassing). Especially in these contexts the danger is double: epistemological and political.

From an epistemological viewpoint, the ‘minority’ exhibitions run the risk of emerging as a mere footnote at the bottom of the page of the great narratives of the dominant historiographies. They seem to say “it’s true that modern art was mainly made for and by white central European men, but lets not forget about Sonia Terk, Liubov Popova, Claude Cahun, Dorothea Tanning… see how every now and again, although in the shadows, they make lovely little masterpieces!?” Many exhibitions respond to a paradigm that could better be described with a phrase uttered by an editor of Playboy: “There weren’t any women or black people in art, just as there weren’t any bikinis in the North Pole”.

From a political point of view, exhibitions concerned with the minorities can be roughly classified into two groups, depending on the criteria through which the selection of works is made. Many are “universalist” while others operate the logic of “the politics of identity”. With the universalist approach (the dominant trend in French institutions) the important thing isn’t that the works were made by “women”, “homosexuals”, the “mentally ill” or “non-white” people but that the experience represented allows access to a universal —or rather, it can be absorbed by the hegemonic narrative. On the other hand, when the “politics of identity” is at stake, other dangers spring up: how is it decided that artists are women, mentally ill or homosexuals? Do we use anatomical criteria, clinical archives, chromosomic evidence, speech acts, confessions found in personal diaries? In all of these example the risk is the same: in the place of demonstrating the techniques of normalisation of gender and sexuality, the majority of exhibitions by “women”, the “crazy”, “homosexuals”, “blacks” or “indigenous peoples” contribute to the re-naturalisation of these categories, integrating these ‘differences’ into the grand narrative as anecdotes (a sort of memorial of victims that is useful for celebrating women’s day or the day of the abolition of slavery). Far from dismantling the hegemonic narratives, they end up being reaffirmed.

I suppose it is for some of these reasons that until now I have been hesitant to face up the exhibition. But this time, the subject is Carol Rama.

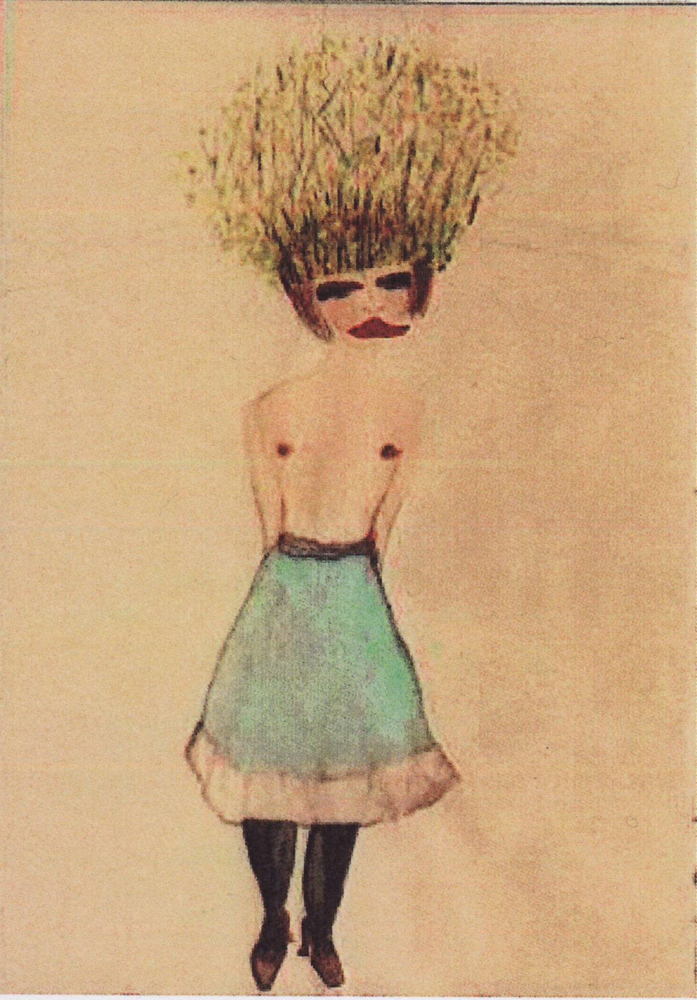

Carol Rama’s work produced between 1936 and 2006, is monumental and yet nearly entirely unknown. An exhibition of her work could function as a counter-archive of the art of the twentieth century and allows for a critical re-reading of the dominant historiography and a questioning of its foundations. Carol Rama’s work is as masterly as it is subversive, as marginal as it is irrefutable. I would even dare to say that Carol Rama will be one day as indispensable and significant as Frida Khalo and Louise Bourgeois are now.