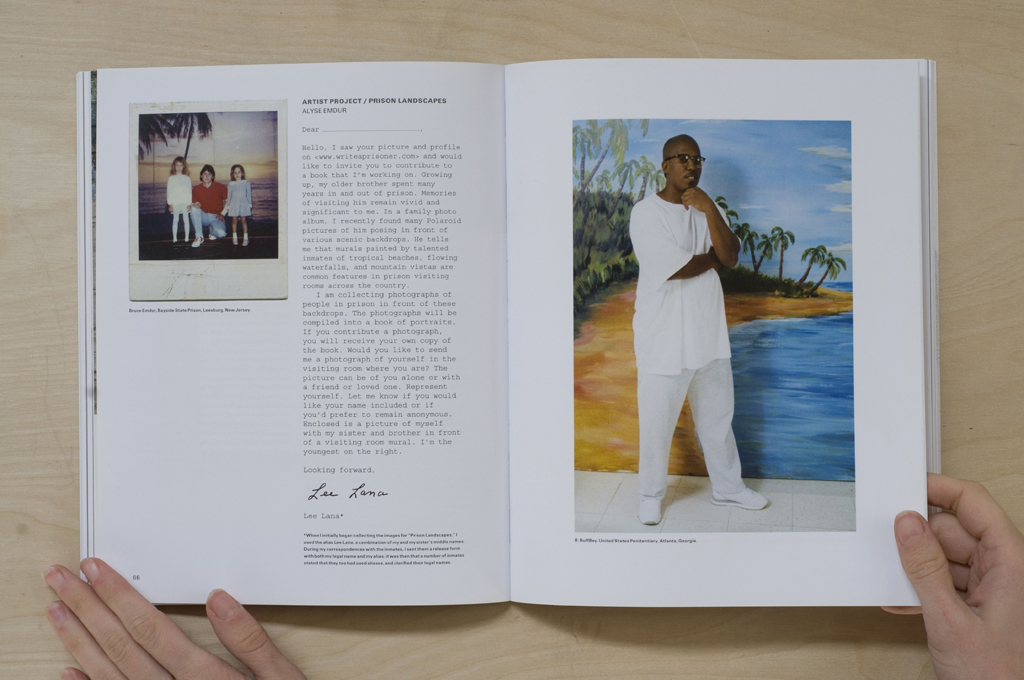

Alyse Emdur, Prison Landscapes, Collection and Correspondence, 2008-2011, Cabinet Magazine, Issue 37

Ci-dessous se trouve un compte-rendu écrit spécialement pour ce blog par Stéphane Symons, mon collègue de l’université de Louvain. Il a eu l’occasion privilégiée de visiter l’exposition Aesthetic Justice qui se tient à New York jusqu’au 22 juin 2011 (Lambent Foundation). Elle est organisée par Provisions Learning Project, un centre de recherche et de production examinant les croisements de l’art et de la réforme sociale.

Provisions est un acteur de premier plan pour faire avancer la connaissance et promouvoir la compréhension de nombreux sujets sociaux, en produisant des modèles innovants pour une recherche critique. Avec sa vaste bibliothèque, sa programmation publique et ses opportunités de recherche, il supporte des démarches artistiques, intellectuelles ou activistes qui explorent les dimensions sociales de la culture contemporaine. Provisions présente dans ses lieux des programmes tels que des expositions, des projections, des ateliers, des conférences, ainsi que des publications (online ou non), pour lesquels ils collaborent avec diverses organisations artistiques, éducatives ou philanthropiques à travers le monde.

« Plus on est conscient de ses tendances politiques, écrivit un jour George Orwell, plus on a de chances d’agir politiquement sans sacrifier son intégrité esthétique et intellectuelle ». Cette relation complexe entre esthétique et politique est l’un des enjeux centraux de l’exposition Aesthetic Justice. Enserrée de près, au Nord, par la base stratégique du capitalisme global – le Wall Street Stock Exchange n’est qu’à un bloc de là – et, au Sud, par la Statue de la Liberté, l’exposition présente les travaux de cinq artistes tournés vers quatre contextes spécifiques de domination sociopolitique, dans une tentative de renouveler notre compréhension des concepts de justice et de liberté. Carlos Motta et Josué Euceda, Alyse Emdur, Rajkamal Kahlon et Larissa Sansour abordent les problématiques des brutalités policières au Honduras, du complexe pénitentiaire industriel aux USA, de la torture de prisonniers irakiens et afghans par le gouvernement américain et la situation désespérée du peuple palestinien, et ce, afin « d’explorer de quelle manière des stratégies formelles et conceptuelles favorisent une meilleure compréhension de la responsabilité et de la réceptivité », ainsi que le présente Niels Van Tomme dans un texte qui accompagne l’exposition.

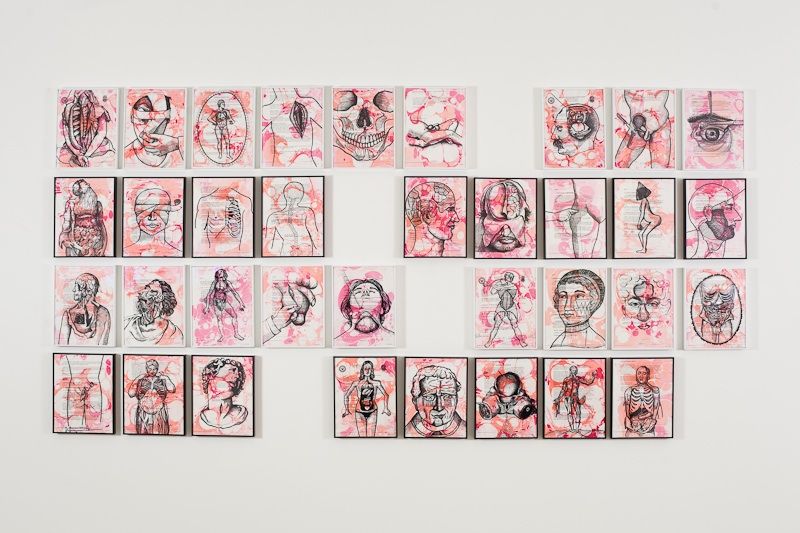

Les œuvres sont aussi variées que les enjeux sociopolitiques auxquels elles se confrontent. Des photographies de prisonniers américains posant devant des toiles de fond maladroitement peintes sont montrées à côté d’une installation vidéo dans laquelle un homme latino-américain nous raconte les violences policières infligées aux manifestants pacifiques. Un peu plus loin, on trouve des scènes de tortures médiévales dessinées à l’encre noire sur des rapports d’autopsie de détenus irakiens ou afghans et, face à eux, de l’autre côté de la pièce, un pastiche vidéo de 2001, Odyssée de l’espace, mettant en scène un astronaute fictif qui plante le drapeau palestinien sur la lune.

Les cinq artistes réunis dans l’exposition partagent le sentiment que les œuvres d’art s’imprègnent d’une pertinence politique et d’une signification sociale aux moyens d’éléments spécifiquement esthétiques, et non malgré eux. Les photographies et installations ne sont pas de simples visualisations de problèmes sociaux qui leur sont externes, pas plus qu’ils ne soulignent un sens politique qui puisse être séparé des œuvres exposées. Il semble donc essentiel au concept de justice esthétique que les œuvres soient considérées politiques en tant qu’elles sont œuvres, et que les références aux enjeux sociaux soient perçues comme le résultat d’un langage purement artistique. Le grain et la nature impersonnelle des images de webcam ainsi que le ton détaché avec lequel un homme rend compte de la violence policière dans Resistance and Repression de Carlos Motta et Josué Euceda, par exemple, ne rendent certainement pas l’installation moins lisible. Au contraire, c’est précisément sur base de ces qualités intrinsèquement artistiques que l’on peut affirmer qu’elle a capté à la fois l’urgence et les difficultés propres à toute tentative de narrer un événement traumatique. De même, la pièce Prison Landscapes de Alyse Emdur ne parvient à témoigner du profond désespoir derrière la situation des détenus et de leur désir ardent d’un contact humain, que parce qu’elle évite tout récit précis. Les lettres exposées aux côtés des photographies fonctionnent comme des légendes qui injectent des fragments d’histoires au cœur d’images anonymes et qui projettent des émotions incertaines sur des visages inconnus : elles donnent par là une information au sujet de l’identité et de la situation des modèles, mais sans jamais mettre en lumière, dans le même temps, la nature ambiguë et indéterminée du médium photographique. De cette manière, la juxtaposition étrange de poses sérieuses et de décors maladroitement peints ne communiquent pas seulement une atmosphère de désarroi, mais elle accroit tout autant la beauté des images et intensifie notre sentiment de proximité. C’est comme si les éléments indéniablement faux de ces photos leur permettaient de communiquer véritablement certains des sentiments les plus intimes des détenus.

Aesthetic Justice s’inspire des derniers écrits de Judith Butler au sujet de la fragilité et de la vulnérabilité de toute existence humaine, et les six œuvres présentées, par leur exploration des moyens avec lesquels l’esthétique peut à la fois exprimer et dépasser la fragilité essentielle des victimes de la domination sociale et politique, sont exemplaires. Les scènes de mutilation du projet Did You Kiss the Dead Body de Rajkamal Kahlon, par exemple, ne sont pas du tout agréables à regarder, et les rapports d’autopsie de prisonniers torturés sur lesquels ils sont dessinés ne sont rien moins que froids, cruels et cyniques, mais ils assurent toutefois une touche profondément humaine et distinctement poétique. Car c’est presque comme si les dessins eux-mêmes exécutaient un rite funéraire posthume pour les prisonniers dont les décès anonymes sont rapportés de manière impersonnelle dans les comptes-rendus médicaux et militaires. Quelle que soit la brutalité des scènes dépeintes par ces dessins, et probablement pour nulle autre raison que leur réalisation par une main humaine, ils garantissent qu’une injustice flagrante ne passe pas inaperçue et ils empêchent ainsi les documents officiels de l’autopsie de clore le dossier de décès dont les circonstances demandent encore à être clarifiées. Pour des raisons similaires, la vidéo de Larissa Sansour Palestinauts ne devrait pas être envisagée comme un pastiche ironique au sujet d’une situation si complexe et inflexible qu’aucun espoir réaliste d’une issue équitable ne soit envisageable. L’œuvre de Sansour transpose la sensibilité de Prison Landscapes dans le contexte géopolitique du Moyen-Orient car elle parvient à capturer, à l’instar d’Emdur, une dimension essentielle de la réalité au moyen d’images ouvertement non-réalistes. Comme dans l’œuvre d’Emdur, les exagérations évidentes dans le langage visuel des Palestinauts doivent être interprétées à contre-courant puisqu’elles indiquent précisément l’urgence d’une situation sociopolitique injuste et le niveau de désespoir atteint par tous ceux qui sont impliqués dans le conflit.

Aesthetic Justice, pour résumer, est une exposition de petite taille mais néanmoins importante, traitant d’enjeux cruciaux à l’heure actuelle. Motta et Euceda, Emdur, Kahlon et Sansour révèlent que certaines formes de domination sociopolitique sont si extrêmes que seul l’art peut rappeler la réalité à l’ordre, non pas afin de la juger ni même de déterminer qui est responsable et qui ne l’est pas, mais pour créer une réceptivité nouvelle à des exigences et à des aspirations trop fragiles pour être recueillies autrement. Les cinq artistes sont tous engagés dans une éthique de l’impossible et ils découvrent, comme Spinoza avant eux, la puissance et la réalité qui réside dans la simple capacité humaine à imaginer des choses et des situations, aussi inexistantes et irréelles qu’elles puissent être.

Stéphane Symons est chercheur postdoctoral au Fonds de la Recherche-Flandre. Il enseigne à l’institut de philosophie de l’Université catholique de Louvain (KULeuven, Belgique). Ses recherches portent sur la philosophie de l’art et l’esthétique des XIXe et XXe siècles, principalement françaises et allemandes. Il achève actuellement un livre sur Walter Benjamin (bientôt édité chez Edwin Mellen Press) et a publié notamment sur Georg Simmel, Siegfried Kracauer, Gilles Deleuze et Jacques Lacan.

Le 14 mai 2011, à la Hispanic Federation, Las Americas Conference Center, a eu lieu un séminaire sur le thème de la justice esthétique, organisé par Thomas Keenan et Niels Van Tomme. Il explorait les intersections entre le domaine des droits de l’homme et les pratiques artistiques et discutait l’influence de ces dernières sur la notion de justice et sur sa pratique.

Pour plus de renseignements sur l’exposition, voir : Provisions Learning Project

Provisions Learning Project is a research and production center investigating the intersection of art and social change. Provisions is a leading voice in advancing knowledge and promoting understanding on a wide-range of social topics, producing innovative models for critical investigation. With its extensive library, public programming, and research opportunities, it supports artistic, intellectual, and activist endeavors that explore the social dimensions of contemporary culture. Provisions features on-site programs such as exhibitions, screenings, workshops, lectures, as well as on- and offline publications, for which it collaborates with various artistic, educational, and philanthropic organizations nation-wide.

“The more one is conscious of one’s political bias,” George Orwell once wrote, “the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.” This complex relationship between aesthetics and politics is one of the central issues in the exhibition Aesthetic Justice (Lambent Foundation, New York City, on view through June 1, 2011), hosted by the Provisions Learning Project, a not for profit research, education and production center that investigates the intersection of art and social change. Tightly squeezed in between the power base of global capitalism in the north –the Wall Street Stock Exchange is a mere block away- and the Statue of Liberty in the south, the exhibition presents works by five artists who turn to four specific contexts of socio-political dominance in an attempt to renew our understanding of the concepts of freedom and justice. Carlos Motta and Josué Euceda, Alyse Emdur, Rajkamal Kahlon and Larissa Sansour engage with the issues of police brutalities in Honduras, the US prison industrial complex, the torture of Iraqi and Afghan prisoners by the US government and the plight of the Palestinian people in order to “explore the ways in which formal and conceptual strategies enhance an understanding of responsibility and responsiveness”, as curator Niels Van Tomme puts it in a text that accompanies the exhibition.

The works are as diverse as the socio-political issues they deal with. Photographs of American prisoners posing against clumsily painted backdrops are shown side by side with a video installation of a Latin American man telling us about police violence deployed against peaceful protesters. A bit further on we find medieval torture scenes drawn in black ink over the autopsy reports of Iraqi and Afghan inmates and, facing them from the other side of the room, a video pastiche of 2001, A Space Odyssee centered around a fictitious astronaut who plants the Palestinian flag on the moon.

All five of the artists included in the exhibition share a feeling that artworks become impregnated with political relevance and social significance by virtue of specifically aesthetic elements and not despite of them. The photographs and installations are no mere visualizations of social problems that are external to them nor do they spell out a political meaning that can easily be divested from the works on show. It seems crucial to the concept of aesthetic justice, therefore, that artworks are considered to be political as artworks and that references to societal issues are perceived as the outcome of a purely artistic language. The graininess and impersonal nature of the webcam image and the detached tone in which a man presents his account of police violence in Carlos Motta and Josué Euceda’s Resistance and Repression, for instance, do not at all make the installation less legible. It is, on the contrary, precisely on account of these inherently artistic qualities that it can be said to have captured both the urgency and the difficulties that mark all attempts to narrate a traumatic event. Similarly, Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes only manage to testify to the profound desperation behind the inmates’ situation and to their heartfelt longing for human contact because they defy any clear-cut narrative. The letters shown alongside the photographs function like captions that inject fragments of stories into anonymous images and they project unclear emotions onto unfamiliar faces: they do thereby give information about the identity and situation of the sitters but never without at the same time highlighting the ambiguous and underdetermined nature of the photographic material. In this way, the strange juxtaposition of serious poses with clumsily painted backdrops does not merely convey an atmosphere of dismay but it just as much enhances the beauty of the images and it increases our feelings of proximity. It is as if only the obviously phony elements in these photos allow them to truly communicate some of the inmates’ most intimate sentiments.

Installation shot Aesthetic Justice, Rajkamal Kahlon, 5 Men from Did You Kiss the Dead Body Project, 2010-2011. Ink on Marbled U.S. Military Autopsy Reports, 35 drawings; each 8 1/2 x 11 in. Overall dimensions variable © Kelly Neal, 2011

Aesthetic Justice takes its cue from Judith Butler’s recent writings on the weakness and vulnerability of all human existence and, in exploring the ways in which aesthetics can both express and move beyond the essential fragility of the victims of social and political dominance, the six works on show are exemplary. The mutilation scenes from Rajkamal Kahlon’s Did You Kiss the Dead Body Project, for instance, are not at all pleasant to look at and the autopsy reports of the tortured prisoners over which they are drawn are never anything less than stone cold, cruel and cynical; yet, they do nevertheless maintain a deeply human and a distinctly poetic touch. For it is almost as if the drawings themselves perform a posthumous funerary ritual for the prisoners whose anonymous deaths are being so impersonally laid down in the medical and military reports. Regardless of how brutal the scenes in these drawings may be and most likely for no other reason than that they were made by a human hand, they have made sure that a blatant injustice did not pass by unwitnessed and they thus prevent official autopsy documents from closing the book on circumstances of death that are still waiting to be clarified. For similar reasons, Larissa Sansour’s video Palestinauts should not be regarded as an ironic pastiche on a situation that is so complex and unyielding that no realistic hopes for a just outcome can be maintained. Sansour’s work transposes the sensibilities of the Prison Landscapes to the geopolitical context of the Middle East for she, like Emdur, manages to capture an essential dimension of reality in images that are overtly non-realistic. Similar to Emdur’s work, the obvious exaggerations in the visual language of Palestinauts need to be read against the grain since they indicate precisely the urgency of an unjust socio-political situation and the level of desperation reached by all those who are involved in the conflict.

Aesthetic Justice, in short, is a small but important show that deals with issues that are crucial today. Motta and Euceda, Emdur, Kahlon and Sansour reveal that some forms of socio-political dominance are so extreme that it is only in art that reality can be called to order, not in order to judge over it, nor even to determine who is responsible and who is not, but to create a renewed responsiveness to demands and longings otherwise too fragile to be picked up. All five artists are committed to an ethics of the impossible and they discover, like Spinoza already did before them, the power and reality that reside in the mere human ability to imagine things and situations, however non-real and non-existing these may be.

Stéphane Symons is a Post Doctoral Research Fellow at the Research Fund- Flanders. He teaches at the Institute of Philosophy at KULeuven (Belgium). His research interests are nineteenth and twentieth century philosophy of art and aesthetics, mainly French and German. He is currently finishing a book on Walter Benjamin (forthcoming with Edwin Mellen Press) and has published on, a.o. Georg Simmel, Siegfried Kracauer, Gilles Deleuze and Jacques Lacan.

On May 14, 2011, at the Hispanic Federation, Las Americas Conference Center, a seminar on the theme of Aesthetic Justice took place. Organized by Thomas Keenan and Niels Van Tomme, it aimed to explore the intersections between artistic practices and the field of human rights, and to discuss implications for the notion and practice of justice.

For more information on this exhibition, see: