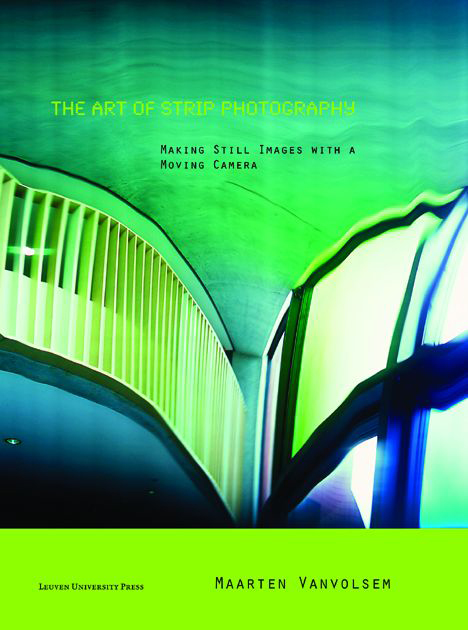

Dans la Lieven Gevaert Series vient de paraître un onzième volume, de Maarten Vanvolsem, conférencier spécialiste de la photographie à l’École Supérieure des Arts de Saint-Luc (Sint-Lukas) à Bruxelles et associé de recherche au Lieven Gevaert Research Centre for Photography à l’Université catholique de Louvain (KULeuven).

Voici un résumé du livre:

Photographic images can, apart from their capacity to show, convey an experience – a quality that has seldom been recognized. In this book the artist and photographer Maarten Vanvolsem explains how the strip technique can tell a different story of time and space in photographic images, a story that leads to new expressions and experiences of time and movement. The strip technique itself seems to be neglected in the debate on time and photography, although it has a long history. Its use is widespread and, especially in recent years, more and more artists rediscover the technique. Based on an historical overview, a knowledge and understanding of the technique, and experiments with the building of cameras, this book will propose a new use of this forgotten art: a use in which the temporal terms ‘speed’, ‘rhythm’, and ‘pace’ are of more value than terms so often associated with photography such as ‘freeze’, ‘split second’, or ‘capture’. Within the book one can find more than thirty artists using the strip technique for their artistic practice. A lot of the artwork produced goes beyond traditional photography and the standards set by the photo industry. The research also reveals the extent to which artists use the technique to rediscover the time-based possibilities of the photographic image.

The Art of Strip Photography est un livre exemplaire, qui démontre, parmi bien d’autres choses, l’utilité d’un centre de recherche qui rassemble aussi bien la réflexion théorique que pratique. Voici quelques unes de mes pensées à ce propos:

In 2004, the K.U.Leuven decided to provide impulse funding, in order to support the founding of a research centre, by Jan Baetens and myself. It was named after a pioneering figure in the Belgian photography industry. Since 2008, the centre is bi-university based (in Leuven and in Louvain-la-Neuve), and is directed by both Alexander Streitberger and myself. Within the framework, the Centre, Jan Baetens and I supervised the first practice-based PhD in the Visual Arts completed in Belgium by Maarten Vanvolsem in 2006, on The Experience of Time in Still Photographic Images.

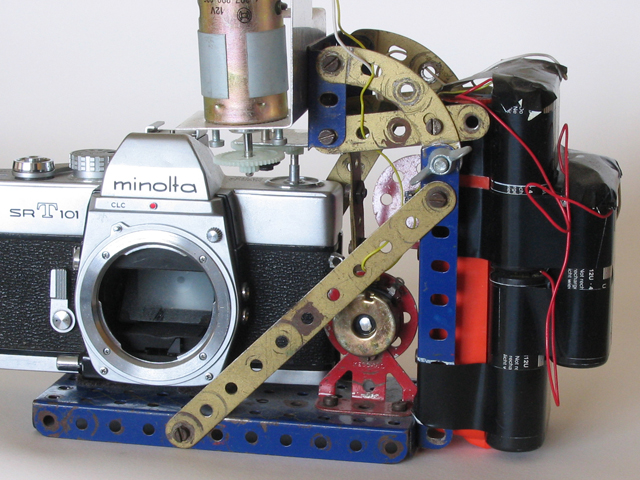

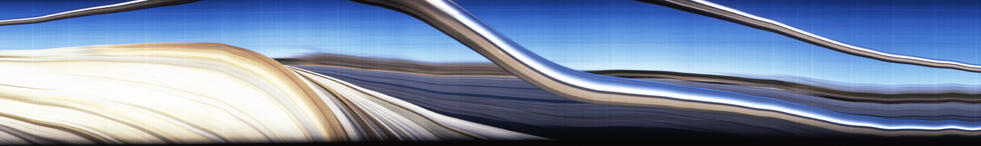

Maarten Vanvolsem’s elongated horizontal prints of large parts of photographic films or of entire photo films have gained a solid international reputation. He produces these images by means of a self-built camera in which a film moves before an open shutter at the speed that the artist turns a manual handle. More recently, he is also experimenting with a handheld, digital camera. Fundamental in the making process of these works is that their shooting involves time: it takes much longer than just a split-second moment of ‘pressing the button’ to produce them.

The spectator’s perceptive process of these works as well operates on various levels of temporality. One can decide to try to visually take them in all at once, but that is quite a confusing operation. As these images rapidly appear to be somehow internally unfolding themselves, instant comprehension is hampered. Only a carefully extended temporal apprehension allows for a full understanding of the fact that the images offer a distorted impression of a particular space, landscape or person. While the earliest 19th Century photographs were reputedly ‘slow’ in their own making – a daguerreotype took about fifteen to thirty minutes – ever since William Henry Fox Talbot was able to reduce the exposure time for paper negatives to one second in the early 1850s, the general opinion with regard to the relationship between photography and time has been that photography is an instantaneous medium.[1]

Vanvolsem’s images profoundly put in perspective this dominant, modernist logic of the photograph as being a snapshot that demonstrates how the photographer’s flashing push of the camera button immobilizes a decisive moment in time – understood as the photographic freezing of a fraction of a second. In his work, there is no instantaneous automatism. Duration becomes an integral element of the entire production process. It took him, as the photographer, more than a split-second to make the image: the final result thus reflects a temporally extended part of the artist’s own lived time.

In order for Maarten Vanvolsem to theorize this fundamental aspect of his photographic practice, he had to take recourse to art history and art theory. This is the moment when our research relationship as supervisor and doctoral student developed into a fruitful exchange in expertise. In my own doctoral dissertation in art history (KULeuven, 2000), entitled Temporality and the Experience of Time in Art of the 1960s, I had come to interpret late 1960s and early 1970s post-minimalist, material art practices such as those of Robert Morris, Hans Haacke, Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Michael Snow and Dan Graham as reflecting what Robert Smithson calls « the time of the artist. » [2] In this conception, the work of art « contains its making time. It is a trace of its making process, or an index of its own production. »[3]

This understanding of the artwork as a « container of amassed time », as I put it (2004: 85), became crucially important to Vanvolsem’s comprehension of what is at stake in his own work. Previous ideas of the artwork bearing witness of its making time and thus possessing an inherent temporal dynamic had been expressed by Etienne Souriau’s concept of the « intrinsic time » of an artwork.[4] Building on this concept, my dissertation brought forward a hypothesis as to how this intrinsic time of the artwork – as a container of the time of the artist – both determines and steers the spectator’s temporal/durational perception and understanding of the artwork.

In his dissertation chapter on the perceptual reading of his strip technique photographic images, Vanvolsem explains how crucial this notion of the intrinsic time of the work of art has been in coming to terms with what is at stake in his own photographs. He argues that, with their distortions of landscapes, changes from sharp to blurred and fleeting vanishing point, repetition of depicted objects, and size, his strip photographs disrupt all that would possibly have been left concerning the basic consensus that a photograph is a true representation of the world. The strip photograph comes out as alienated from reality, as the depicted space is only vaguely reminiscent of what the real world original looks like.[5]

This « alienation » pushes the viewer to a closer and longer inspection of the image than one would usually do for a snapshot. What becomes visible then to the viewer, is the « displacement of the photographer during the making of the image » (158), Vanvolsem writes. As an active participant, the viewer thus has to ‘remake’ the image before understanding what is depicted in it. He concludes:

« This remaking of the movement in space translated itself in an experience of time. It is the exploration of the image, its surface, its process that leads to the photographer as maker of the image, and evokes the active experience of looking (158). » Whereas an exchange with my previous research on the topic of time and the image appeared central to Vanvolsem’s doctoral research, his findings in their turn have thoroughly influenced the thoughts that Helen Westgeest and I develop in a chapter from our book, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective. We build upon Vanvolsem’s argument and assess that his images can be understood as engaging in a multiplication of temporal viewing processes, as the differences in sharpness along the image generate different reading speeds:

« Each change from sharp to blur, or, vice versa, from blur to sharp, will cause the movements of the spectator’s eyes to accelerate or decelerate (84). »

Both Maarten Vanvolsem’s research and that of Helen Westgeest and myself have substantially benefited from our longstanding, close interaction over the years. Most probably, neither of us would have come to similar conclusions if we had proceeded with our research independently from one another. We have mutually progressed in an inestimable way, to the benefit of research in the domain of art in general.

Researchers in the wider field of art today ask critical questions about our conceptions of the idea of knowledge.[6] Convinced that they can provide an inspiring tool for widening the governing scientific and academic frameworks, they also claim that the opening of the field of artistic discourse, reflection and production into a domain where, for centuries, it did not naturally belong (the university as distinct from the ‘academy’), offers artists new instruments in order to make statements about the reality surrounding us.

Art research, as this new type of research is now increasingly defined,[7] can provide an engaged alternative to commercially embedded art. Situated in the joint collaborations between universities and art colleges, art research fulfils a crucial role in offering a new way to anchor art in today’s society, and giving it the critical cultural voice that our society needs. It is exactly in this fascinating area that the LGC wishes to operate.

[1] For a more detailed exposé of this development, see H. Van Gelder and H. Westgeest, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective. Case Studies from Contemporary Art, Boston, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, 74-76 and 85-88.

[2] R. Smithson, ‘A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,’ in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. by J. Flam, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, University of California Press, 1996, 112. First published in Artforum, VII, 1 (September 1968): 44-50.

[3] H. Van Gelder, Temporality and the Experience of Time in Art of the 1960s, doct. diss., KULeuven, 2000, 208; see also my ‘The Fall from Grace. Late Minimalism’s Conception of the Intrinsic Time of the Artwork-as-Matter’, Interval(le)s—I, 1 Fall 2004: 94. – http://www.ulg.ac.be/cipa/pdf/van%20gelder.pdf

[4] Etienne Souriau, ‘Time in the Plastic Arts,’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, VII, 4 (June 1949): 294-307; see my Temporality and the Experience of Time in Art of the 1960s, 21-25.

[5] M. Vanvolsem, The Experience of Time in Still Photographic Images, doct. diss., KULeuven, 2006, 201. The passage is included in Vanvolsem’s The Art of Strip Photography: Making Still Images with a Moving Camera, Leuven, University Press Leuven, 2011, 157-158.

[6] This is expanded in H. Van Gelder and J. Baetens, ‘On the body as the subject of experience: art as a necessary element of the genesis of knowledge’, Image [&] Narrative, 9 (October 2004). Available at: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/performance/vangelder.htm.

[7] See http://www.workshop.ciac.pt/.

Pour plus de renseignements sur ce livre, voir:

La Lieven Gevaert Series est distribuée en Amérique du Nord par Cornell University Press. Voir:

Pour plus de renseignements sur la Lieven Gevaert Series, voir: