Wendy Morris, page et collage extraits de son livre de promenade 'Religious walks for an atheist', reflétant ses impressions de la promenade 49, 2011. Copyright Wendy Morris.

Avec cet article, la trilogie des textes de Wendy Morris sur ce blog se complète. Il s’agit du vingt-deuxième envoi dans la série de cinquante-deux lettres qu’elle continuera d’envoyer pendant l’année 2011 à un groupe de correspondants prédéterminé. Dans ce texte, elle parle de la tension entre son propre athéisme et la religiosité extrème de ses ancêtres, qui sont partis coloniser l’Afrique du Sud. Ainsi, sa méthode artistique et ce qui précède la production de ses films sortent de l’ombre.

Il y eut d’abord l’idée d’enregistrer le son dans mon studio. C’était le printemps, la porte de mon studio était ouverte et les sons du monde extérieur y pénétraient. J’allumai donc mon iPod pour enregistrer et je le laissai ainsi pendant que je travaillais plus loin. Sachant qu’il enregistrait, je devins également très attentive aux sons dans la pièce. Le bruit des touches du clavier d’ordinateur, le grincement de ma chaise, une mouche traversant la pièce.

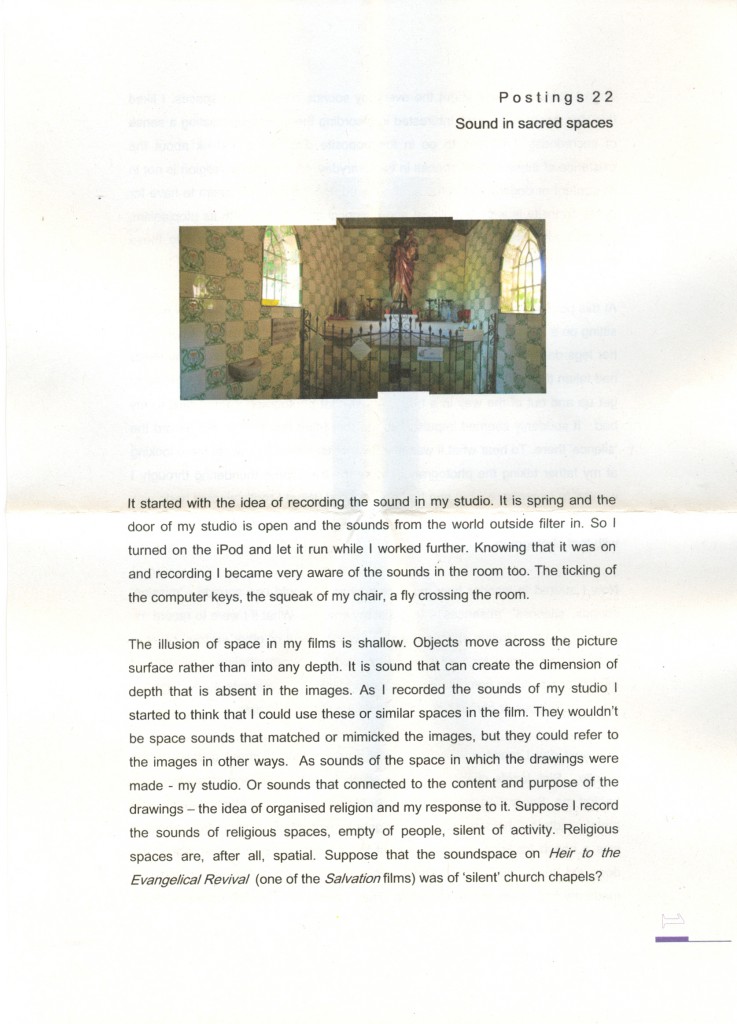

Dans mes films, l’illusion de l’espace est assez superficielle. Les objets se déplacent sur la surface de l’image plutôt que dans une quelconque profondeur. C’est le son qui peut créer la dimension de la profondeur, absente des images. Tandis que j’enregistrais les sons de mon studio, j’en vins à penser que je pourrais utiliser ces sons ou d’autres encore venant d’espaces similaires, pour un film. Ils ne s’agirait pas de sons spatiaux directement associés aux images ou les imitant, mais ils pourraient s’y référer de différentes manières. En tant que sons de l’espace dans lequel furent réalisés les dessins – mon studio. Ou en tant que sons qui étaient connectés au contenu et à l’intention présidant aux dessins – l’idée de religion organisée et ma réponse à celle-ci. Imaginons que j’enregistre les sons d’espaces religieux, vides de monde, sans activité. Après tout, les espaces religieux sont spatiaux. Imaginons que le paysage sonore de Heir to the Evangelical Revival (un des films appartenant à Salvation, le cycle de nouveaux films que je prépare pour 2012) provienne de chapelles « silencieuses » ?

Alors je commençai à penser aux sons quotidiens des espaces sacrés. J’aimais cette idée parce que je ne cherchais pas à enregistrer le sacré ni à créer un sentiment de sacré. Je voulais aller dans la direction opposée en réfléchissant à l’existence de ces espaces sacrés au quotidien. Mon intérêt pour la religion ne porte pas sur son contenu ou sur le dogme, ni sur le fait que la plupart des gens manifeste pour elle un étrange besoin. Ma curiosité concerne son importance politique et historique, avec son caractère utopique mais aussi ses aspects triviaux. Enregistrer les sons du quotidien filtrant dans ces espaces pourrait être une manière intéressante de les approcher.

Et si j’enregistrais ma voix dans des espaces religieux vides – c’est-à-dire vides de croyants ou d’autres visiteurs ? J’ai écrit un monologue pour Heir (qui fait également partie de Salvation) dans lequel j’examine mon propre athéisme à la lumière de l’engagement très fort des mes aïeux dans divers mouvements religieux. Je pourrais commencer par enregistrer des phrases ou des expressions de ce monologue dans ces espaces.

Le jour suivant, je sortais de chez moi pour me rendre dans un certain nombre de chapelles de rue, dans les environs. Je pus entrer dans la chapelle Saint-Joseph et fermer la porte derrière moi. Un portillon métallique surmontée d’une croix me séparait de la statue de Saint-Joseph, des bougies dans des bouteilles en plastique et des supports métalliques pour les cierges. En face se trouvait un banc pour s’agenouiller et, sur le côté gauche, un petit siège. Je refermai la porte, m’assis et me mis à écouter. Il y avait un son agréable dans cet espace et j’y fis donc mon premier enregistrement d’ « espace silencieux ». Ensuite, j’ouvris « Religious walks for an Atheist », mon livre de promenade dans lequel j’avais écrit la première partie du monologue. Je pris une inspiration mesurée et je commençai à réciter les paroles.

Je me suis interrogée pendant longtemps sur la manière d’aborder ce monologue. Écouter l’enregistrement de ma propre voix me rend anxieuse. Elle sonne fluette et un peu trop aiguë. Elle donne l’impression d’être à la fois prétentieusement anglaise et nettement sud-africaine. Ce monologue est essentiel au film, aux cinq films qui constituent le cycle Salvation. Je l’ai écrit un soir dans un restaurant de Clermont-Ferrand. Off the Record était programmé en 2009 dans la section « Labo » du festival et j’avais été invitée à y participer en tant qu’auteur d’un film sélectionné. La plupart des soirs, j’allais au même restaurant pour manger et travailler sur des idées pour le prochain film. Même lorsque j’étais en train d’écrire ce monologue, je me demandais comment je pourrais le réciter. Je n’avais jamais utilisé aucune voix ou dialogue dans mes films antérieurs, encore moins la mienne. Ma pratique consistait à tenter d’exprimer des idées entièrement au moyen de dessins, en n’ajoutant un mot ou une expression que pour affiner le sens d’une image ou d’une séquence. J’attachais une certaine importance à l’idée d’écrire les paroles mais je ne voulais pas que les spectateurs aient à lire le film. J’avais besoin de trouver une voix, ma propre voix, pour réciter le monologue.

Wendy Morris, Chapelle de Saint Joseph. Dessin de "Heir to the Evangelical Revival", un des films du cycle « Salvation" (2012), juillet 2011, charbon de bois. Copyright Wendy Morris.

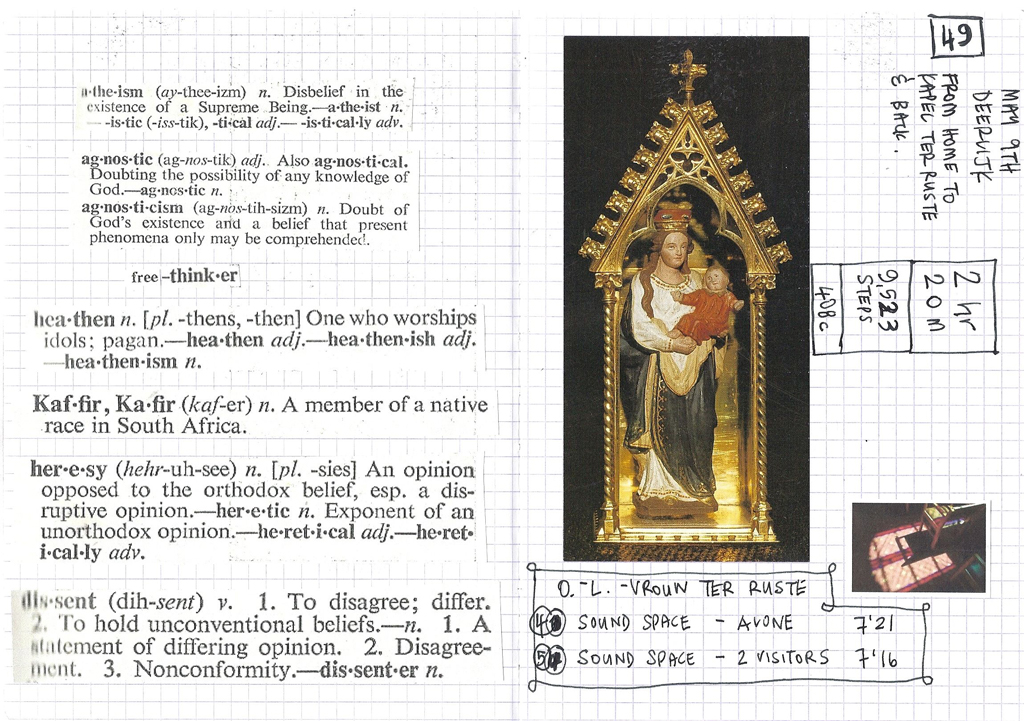

L’enregistrement dans Saint-Joseph ne devait pas être un enregistrement professionnel ; j’aurais probablement eu besoin d’un micro différent pour cela. Mais savoir qu’il ne s’agissait que d’une tentative, cela m’aidait. J’ai commencé, hésitant, tâtonnant au fil des mots : « Je suis athée…agnostique…libre-penseuse… » Cet espace me faisait quelque chose. Je ne pouvais pas prononcer le texte à haute voix ; je m’entendais le murmurer. Je butais sur des mots, que j’avais besoin de répéter. Certains d’entre eux étaient vraiment difficiles à prononcer, tel « kaffir ». Je suis « sud-africaine » : ce mot est problématique et j’entendis ma voix lâcher tandis que j’articulais, osant à peine le prononcer. Dans son sens originel, le mot signifie « païen ». C’est un mot emprunté aux Arabes, lesquels utilisaient Kaffir pour désigner quelqu’un qui n’est pas croyant, un non-musulman en l’occurrence. Les Européens l’appliquèrent ensuite aux Africains, non-croyants au regard de la foi chrétienne. Il devint un terme très dénigrant, destiné à rabaisser et à humilier.

Je me sentais un peu subversive en m’asseyant ainsi dans cet espace magnifique, rempli d’objets déposés par des croyants, et de dire ce que je n’étais pas. Je n’avais jamais eu l’intention d’adopter cet air de subversion. Et à l’instant même où j’éprouvais ce sentiment, je trouvais un peu puéril de faire face à des icônes religieuses dans un espace sacré en déclarant mon athéisme. Je ne souhaitais pas donner l’impression qu’il y avait quelque chose de déloyal dans mes mots. Cela aurait impliqué que je considère qu’il y ait une substance à la religion, à la croyance, ce qui n’est pas le cas. Mais je trouvais aussi qu’il était amusant que moi, depuis longtemps agnostique/athée/libre-penseuse, je me mette à murmurer aux statues en plâtre et aux fleurs en plastique que je ne croyais pas en elles. Et dans l’entremêlement de pensées, de promenades et de dessins qui avaient mené à cet instant, je réalisai que je commençais à trouver un moyen pour intervenir, pour réciter les mots que j’avais écrits. C’était un processus conscient, mais cela fonctionnait. Murmurer ces sentiments dans cet espace leur donnait une dynamique qui aurait tout simplement été absente si je les avais récités dans mon studio.

Visiter des espaces sacrés était devenu un projet itinérant que je commençais à rapporter dans un livre, « Religious Walks for an Atheist ». Tenir ce journal itinérant avait différents objectifs. Je m’entraînais alors pour une marche de sept jours prévue plus tard en 2011 sur la vieille route de pèlerinage menant à Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle en Espagne. J’avais besoin de m’entraîner pour cela mais l’idée de me mettre à niveau n’enflammait pas mon imagination. Cependant j’aime marcher, donc je décidai d’en faire un projet. Je commençai à tenir un journal en Novembre 2010 dans lequel je planifierais et j’enregistrerais mes marches. Il devait y avoir des règles à ce jeu. Chaque excursion devait durer plus d’une heure. Il s’agissait de parcours laïcs dans un monde religieux, incluant des églises, des mosquées, des synagogues, des loges maçonniques mais aussi des routes religieuses et des rues portant le nom de personnages religieux. Je chercherais les traces de religions marginalisées, les absences de juifs, musulmans, groupes dissidents, femmes. A l’occasion de ces marches, je m’instruirais sur l’histoire religieuse de l’Europe et de la Grande-Bretagne. Et tandis que je marcherais, je retournerais à mes propres souvenirs d’éducation chrétienne et j’essaierais de formuler les raisons pour lesquelles je n’aime pas les religions organisées, quelles qu’elles soient. J’écrirais un poème sur chaque marche en utilisant des expressions, des souvenirs ou des mots trouvés sur le chemin ou empruntés à différents livres que j’allais emporter avec moi.

Au moment où je réalisai mon premier enregistrement dans la chapelle, j’avais fait 47 marches. Le livre était devenu épais avec toutes les images et les mots qui avaient été dessinés, écrits ou collés. Les pages étaient abîmées par les nombreuses notes, observations et photocopies trouvées sur les murs des villes ou autres lieux durant les marches. J’avais marché en Belgique, en Afrique du Sud, aux Pays-Bas et en Grande-Bretagne. Il y avait des marches dans les aéroports de trois pays à l’occasion desquelles j’avais cherché les pièces « multiconfessionnelles» parfois présentes. J’avais seulement écrit deux poèmes.

Je pensais qu’écouter à nouveau le premier enregistrement de ma voix allait me paraître inconfortable, mais ça allait. Ok, au départ ça sonnait un peu dramatique, trop secret, trop murmurant, avec trop d’intonation. J’aimais le son de l’espace derrière la voix – le son qu’il peut y avoir sous une petite coupole.

La marche 53 eut lieu dans le district de Schoonhoven dans le sud de la Hollande. Dès que j’eus quitté la périphérie de la ville et que je fus sur la Grote Kerkvliet, un vieux chemin avec des canaux de part et d’autre menant à la Jacobskerk à Cabauw, j’enregistrai un plus grand morceau du monologue. Et cette fois, je ne le murmurai pas. Je le récitai à haute voix tandis que je marchais. Ma voix ne m’effrayait plus, bien qu’à un moment elle effraya un oiseau sorti de son nid. C’était une splendide matinée de printemps, une douce brise soufflait, il y avait des oiseaux partout et, tandis que je marchais, je me répétais le monologue encore et encore. Ca commençait à sonner comme un chant, comme la récitation répétitive d’une prière. Et même si je pense ne pas pouvoir employer cet enregistrement – le son de mes chaussures de marche faisant crisser les pierres sous mes pieds et le vent dans le micro seront trop dérangeants – il y avait quelque chose de libérateur dans le fait de déclarer mon absence de foi à un troupeau de vaches broutant dans les prés.

Version anglaise:

It started with the idea of recording the sound in my studio. It is spring and the door of my studio is open and the sounds from the world outside filter in. So I turned the iPod on to record and let it run while I worked further. Knowing that it was on and recording I became very aware of the sounds in the room too. The ticking of the computer keys, the squeak of my chair, a fly crossing the room.

The illusion of space in my films is shallow. Objects move across the picture surface rather than into any depth. It is sound that can create the dimension of depth that is absent in the images. As I recorded the sounds of my studio I started to think that I could use these or similar spaces in the film. They wouldn’t be space sounds that matched or mimicked the images, but they could refer to the images in other ways. As sounds of the space in which the drawings were made – my studio. Or sounds that connected to the content and purpose of the drawings – the idea of organised religion and my response to it. Suppose I record the sounds of religious spaces, empty of people, silent of activity. Religious spaces are, after all, spatial. Suppose that the soundspace on Heir to the Evangelical Revival (one of the Salvation films) was of ‘silent’ church chapels?

Then I started to think about the everyday sounds of sacralised spaces. I liked this idea because I wasn’t interested in recording the sacred or creating a sense of sacredness. I wanted to go in the opposite direction and think about the existence of these sacred spaces in the everyday. My interest in religion is not in its content or dogma, not in the strange need that most people seem to have for it. My curiosity is with its political and historical importance, with its utopianism, but also with its mundane aspects. Recording daily sounds filtering into these spaces might be an interesting way to approach them.

What if I were to record my voice in empty religious spaces – empty of worshippers or other visitors that is. I have written a monologue for Heir in which I consider my own atheism in the light of my forebears strong commitment to various religious movements. I could start to record sentences or phrases of that monologue in these spaces.

The next day I made a walk from home to a number of street chapels in the vicinity. Sint-Jozefs chapel is one in which I could enter and close the door behind me. Separating me from the statue of Saint Joseph, candles in plastic bottles, and metal candlestick holders, was a metal gate topped with a cross. In front of which was a bench for kneeling upon, and at the left side a small seat. I closed the door, sat down and listened. There was a pleasant ring to the space and so I made my first ‘silent space’ recording. Then I opened my ‘Religious walks for an Atheist’, my walking book into which I had written the first part of my monologue, took a measured breath and began to speak the words.

I have been wondering about how to approach this monologue for a long while. Hearing my recorded voice makes me edgy. It sounds thin and a little too high-pitched. It comes over as both pretentiously English and flatly South African. This monologue is central to the film, to all the five films of the cycle Salvation. I wrote it one evening in a restaurant in Clermont-Ferrand. Off the Record was showing in 2009 in the Labo section and I had been invited, as author of a selected film, to be at the festival. Most evenings I went to the same restaurant to eat and to work on ideas for the film. Even as I was writing it I wondered how I would ever be able to speak it. I haven’t used any voice or dialogue in the films before, never mind my own. My practice has been to try to convey ideas entirely through drawing, adding a word or phrase in only when I needed it to sharpen the meaning of the image or sequence. I did consider writing the words into the film but I do not want viewers to have to read the film. I needed to find a voice, my own voice, to speak the monologue.

The recording in Sint-Jozef’s wasn’t going to be a professional recording, I would probably need a different kind of mic for that. But knowing it was an attempt only, helped. I started, hesitantly feeling the words: “I am a-the-ist… ag-nos-tic… a free-think-er…”. That space did something to me. I couldn’t say the words out loudly but heard myself whispering them. Some words came out trippingly and I needed to repeat them. Some words were really hard to say, like ‘kaffir’. I am South African, this word is problematic, and I heard my voice drop as I mouthed it, hardly daring to speak it. In its original sense the word means heathen. It is a term taken from the Arabs, who had used Kaffir to mean someone who was not a believer, in their case, a non-Muslim. Europeans then applied the term to Africans, as unbelievers in terms of the Christian faith. It became a very derogative word, intended to slight and to humiliate.

It felt a little subversive to sit in that beautiful space, filled with objects placed there by believers, and to say what I was not. I had never intended this air of subversion. Even as I felt it I thought it a little childish, facing religious icons in a religious space and declaring my atheism. It wasn’t my intention to create the impression that there was something traitorous in my words. That would imply that I felt there was a substance to religion, to belief, which I don’t. But I also thought it was funny, me, long time agnostic/atheist/non-believer, whispering at plaster statues and plastic flowers that I didn’t believe in them. And in the mix of thoughts and walks and drawings that had led up to this moment I realised that I was finding a way to intervene, to speak the words I had written. It was self-conscious, but that was okay. Whispering those sentiments in that space gave them a dynamic that simply would not be there if I was saying them in my studio.

Visiting sacred spaces had become a walking project that I have been recording in a book, ‘Religious walks for an Atheist’. Keeping this walking journal had a number of purposes. I was training for a seven day walk that I would be doing later in 2011 on the old pilgrimage route of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. I needed to train for this but the idea of getting fit didn’t fire my imagination. I like walking though, so I decided to make a project of it. I started to keep a book in November 2010 in which I would plan and record walks. There were to be rules to this game. Each walk had to be more than an hour. These would be secular walks in a religious world, that would include churches, mosques, synagogues, free-mason lodges, but also religious routes and streets with names of religious people. I would be looking for traces of marginalised religions, absences of Jews, Moslems, dissenting groups, women. Through these walks I would educate myself on religious history in Europe and the UK. And as I walked I would return to my own memories of a Christian upbringing and would try to formulate why I don’t like organized or any religion. I would write a poem on each walk using phrases, memories or words found on the way or taken from the different books that I would be carrying with me.

By the time of making the first recording in the chapel I had made 47 walks. The book had become thick with images and words that had been drawn, written or pasted in. The pages were bruised by the many notes, observations, and copies of information I had found on city walls or elsewhere on the walks. I had walked in Belgium, South Africa, the Netherlands and in the UK. There were walks in airports in three countries in which I had searched out the ‘multi-faith’ rooms that are sometimes provided. I had written only two poems.

I thought listening back to the first recording of my voice was going to make me uncomfortable, but it wasn’t too bad. Ok, at first it did sound a little dramatic, too secretive, too whispery, with too much intonation. I did like the space sound behind the voice – the sound of a small domed space.

Walk 53 was in the district of Schoonhoven in South Holland. Once I had left the outskirts of the town and was on the Grote Kerkvliet, an old path with canals on both sides that leads to the Jacobskerk in Cabauw, I recorded a larger piece of the monologue. And this time I did not whisper it. I said it out loud as I walked. My voice didn’t scare me any longer, though at one point it did scare a bird out of her nest. It was a beautiful spring morning, a slight breeze blowing, birds everywhere, and as I walked I repeated the monologue again and again. It begun to sound like a chant, like the repetitious recital of a prayer. And even though I don’t think I can use this recording – the sound of my walking boots crunching stones underfoot and the wind in the mic will be too much of a distraction – there was something liberating about announcing my lack of belief to a herd of cows grazing in the fields.