Ce post présente le travail et la recherche de Bart Geerts, doctorant en art plastique à l’université de Louvain. Ses études et expérimentations se concentrent sur une réflexion approfondie : comment peut-on peindre de manière abstraite aujourd’hui ? Faisant amplement usage du cadre théorique de sa formation en littératures germaniques, l’aventure en peinture de Bart Geerts nous informe, de manière sublimatoire, sur nos relations avec les objets et l’espace dans la société contemporaine.

« J’ai commencé le Diary Project à la fin de l’année 2004. Les règles en étaient très simples et élémentaires. Plutôt que d’employer un carnet de note ou un clavier, j’ai décidé de collecter mes impressions et mes réflexions quotidiennes au sujet du projet en cours, sur des feuilles de papier A4 distinctes. À la fin de la journée, je collais le papier du jour (pour peu que j’en aie produit un) sur celui de la veille. Le papier du premier jour était utilisé comme support pour le papier du deuxième jour, et ainsi de suite. À chaque ajout d’une nouvelle page, ce qui avait été écrit dans la note précédente était définitivement occulté. Étant donné la colle utilisée pour fixer les pages l’une à l’autre, la pile de papier a commencé à se déformer, au point de donner un objet informe et en évolution permanente. Ce qui était écrit sur chaque page constituait chaque fois une sorte d’introduction temporaire au projet lui-même. Mais bien sûr personne – pas même moi – ne sera en réalité capable de relire un jour ce que j’y ai écrit. La forme sans cesse changeante du journal révélait et scellait tout à la fois son contenu. Le visible n’était pas tant en contraste avec l’invisible que dans un rapport de continuité avec lui. Ce qui pouvait être lu et vu ne pouvait être déduit que sur la base de la dernière page visible et de l’imagination du spectateur.

The Diary Project s’approche sensiblement d’une incarnation de la notion de palimpseste, laquelle n’est pas seulement utilisée pour désigner les pages manuscrites qui ont été réemployées, mais aussi pour parler des preuves matérielles de l’accumulation de répétitions dans le développement d’un modèle ou d’un site architectural. The Diary Project fonctionne ainsi comme un compte-rendu visuel de ce qui se perd à jamais dans le processus de développement de toute nouvelle chose, et qui donne lieu à quelque chose qui n’aurait pas pu être prévu au départ. Il représente par là le superflu, le redondant et les chemins négligés en cours de route. Bien que les actes d’inscription aient pu devenir invisibles au regard, ils restent très présents dans la matérialité de l’objet qui fonctionne comme un enregistrement de sa propre création. Sur un plan plus pictural, The Diary Project renvoie à l’acte de sur-peindre. En vertu de sa règle de base, il ajoute une nouvelle couche et une nouvelle dimension au point de départ. Ce qui est créé porte les inscriptions et les cicatrices du processus de création et peut mener à quelque chose d’entièrement différent. L’œuvre vidéo de Matt McCormick The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal (2001)[1] illustre à merveille comment les processus de surpeint peuvent, en réalité, mener à de nouveaux régimes esthétiques qui, à l’instar des parasites, se nourrissent des couches inférieures. La vidéo montre avec ironie comment la lutte des autorités d’une ville contre les graffitis illicites mène en fait à une sorte de revival involontaire des motifs modernistes abstraits dans le tissu urbain. L’acte d’effacement des graffitis, qui consiste à les recouvrir de peinture, mène à un langage complètement nouveau en comparaison du graffiti qui l’a déclenché et qui en a déterminé l’apparence et les dimensions.

Wrapped Painting (2006) prend pour point de départ certains traits du Diary Project. L’œuvre consiste en une bande de toile peinte, monochrome, roulée autour d’un châssis en bois d’une largeur quasi identique. Des fils décousus pendent sur les bords de la toile, où sont encore visibles les trous qui ont permis, un jour, de la fixer pour y peindre. On ne peut être certain que toute la surface de la toile soit réellement recouverte du même bleu, car une grande partie qui se trouve contre le mur et cachée sous d’autres couches de toile, en est invisible. Pour vérifier ses suppositions, le spectateur devrait donc dérouler la toile comme un parchemin. Mais en faisant cela, il détruirait l’œuvre, et commettrait presque un sacrilège en dévoilant ce qui avait été volontairement mis à l’abri du regard.

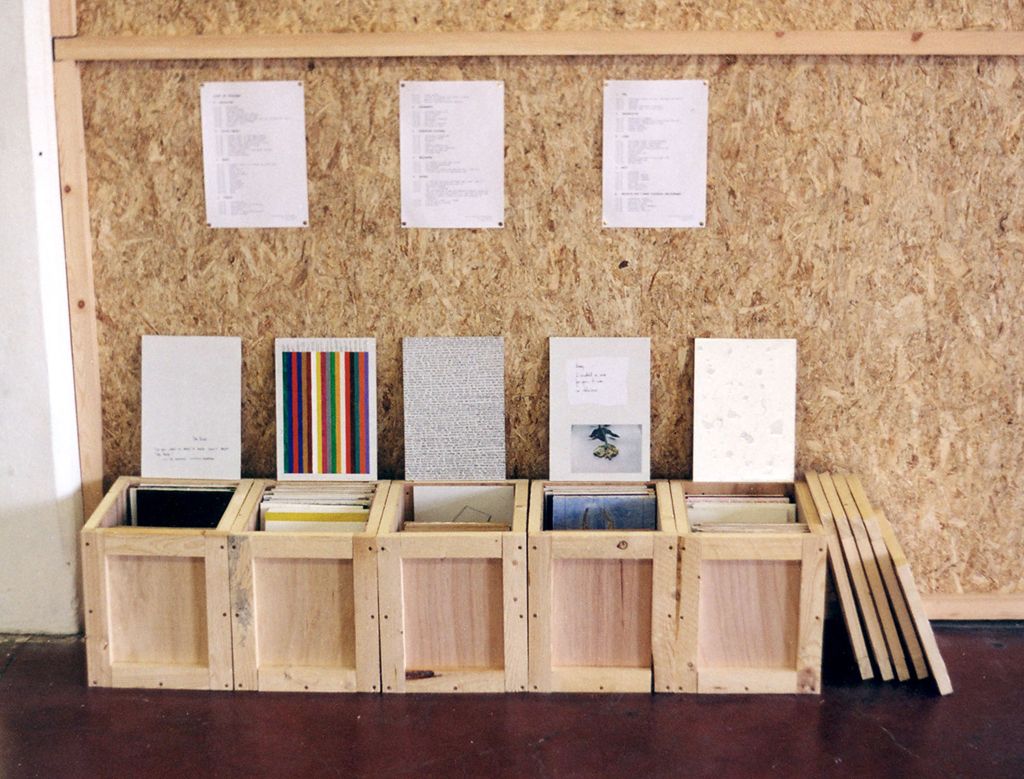

Ceci fait le lien entre ce travail et la continuité visible/invisible présente également dans The Diary Project et qui avait déjà été explorée dans Encyclopedia: Omission#1 (2004). Cette dernière œuvre consiste en 103 panneaux MDF rassemblés dans cinq caisses en bois. Un des panneaux présente un rouleau de papier peint sur lequel est peinte une route. Dans le bas est inscrit le titre du livre de Jack Kerouac On the Road [Sur la route], de même que la légende Perhaps art should be more like wallpaper [Peut-être que l’art devrait ressembler davantage à du papier peint]. Le panneau est inspiré par l’anecdote relative à la manière dont Jack Kerouac a rédigé On the Road. Il aurait écrit le manuscrit original du roman en trois semaines, sur un long rouleau de papier. L’histoire est racontée par Ann Charters dans son introduction au roman.

Dactylographe alerte, Kerouac eut l’idée de taper sans cesse à la machine pour obtenir l’élan de « l’écriture coup de poing » qu’il désirait. À l’instar du poète Hart Crane, il était convaincu que son flot verbal était contrarié lorsqu’il devait changer de feuille de papier à la fin d’une page. Kerouac colla donc ensemble des feuilles de 3,65 mètres de long, raccourcies dans la marge gauche de manière à s’adapter à la machine à écrire, et les introduisit dans celle-ci tel un rouleau ininterrompu. […] Kerouac commença son livre début avril 1951. Le 9 avril, il en avait écrit 34.000 mots. Le 20 avril, 86.000. Le 27 avril, le livre était achevé, sous la forme d’un rouleau de papier dactylographié composé d’un paragraphe en interligne simple de 36,5 mètres de long.[2]

Bien sûr, Wrapped Painting ne comprend aucun texte. Il n’y est question que d’image et de présence matérielle, montrant de quelle manière des couches de toiles peintes sont appliquées l’une sur l’autre. Mais d’une certaine façon, on pourrait dire que cela ressemble à un roman plutôt qu’à une peinture, car le potentiel de ce qui est caché sur la page ou la couche suivante est très présent. En réalité, il n’est pas nécessaire de tourner la page. Nous savons intuitivement que chaque page est couverte des mêmes mots. Peut-être à cause de son vide bleuté, Wrapped Painting semble nous présenter un écran d’incrustation pour notre imagination et nos projections. Il le fait en se référant à la tradition de la peinture, de l’application de peinture couche après couche. Cependant, les couches de peintures sont devenues des couches de toiles, et plutôt que de construire une image de manière transparente, couche après couche, elles voilent autant qu’elles dévoilent. L’objet montre comment la peinture s’est repliée sur elle-même, et comment elle peut à la fois cacher et révéler des choses. »

[1] Un extrait de la video de McCormick peut être regardé en ligne sur http://www.vimeo.com/368367.

Plus de travail par Bart Geerts peut être visualisé via ce lien:

Version anglaise:

« At the end of 2004, I started The Diary Project. The rules of The Diary Project were very simple and basic. Instead of working in a sketchbook, or using a writing pad, I decided to collect my daily impressions and thoughts about the ongoing project on separate A4 papers. At the end of the day, I glued the paper of the day (if any paper had been produced) on top of that of the previous day. Thus the paper of the first day was used as the base for the paper of the second day and so on. Every time a new page was added, the writing of the previous entry was irrevocably hidden from sight. Because of the glue used to fix the pages together, the pile of papers started to deform resulting in an amorphous and ever evolving object. The writings on the pages all functioned as temporary introductions to the project itself. But of course, no one, not even me, would ever be able to actually re-read what I had written down. The diary’s ever evolving shape both revealed and sealed its contents. The visible was not so much contrasted to the invisible, rather it was set in a continuum with it. What was there to be seen and read could only be inferred based on the last visible page on display and on the spectator’s imagination. The Diary Project came very close to embody the notion of a palimpsest, which is not only used to refer to manuscript pages that have been re-used, but also to talk about the material evidence of the accumulation of iterations in the development of a design or an architectural site. The Diary Project thus functions as a visual account of what always gets lost during the process of developing something new, resulting in something that could not be predicted from the onset. In doing so it represents the superfluous and the redundant and the roads not taken along the way. Although the acts of inscription may have become invisible to the eye, they are still very much present in the materiality of the diary object, which functions as a record of its own creation. On a more painterly level, The Diary Project refers to the act of over-painting. Following its basic rules, it adds a new layer and dimension to the starting point. What is being created carries the inscriptions and scars of the process of creation and may lead to something different altogether. Matt McCormick’s digital video work “The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal” (2001)[1] brilliantly illustrates how processes of over-painting can in fact lead to new aesthetic regimes parasitically feeding on the layers beneath. The video ironically shows how the struggle of city officials against all kinds of illicit graffiti in fact leads to a revival without conscious intentions of abstract modernist patterns in the urban fabric. The act of erasing graffiti by painting over it leads to an altogether new idiom in comparison to the graffiti that triggered it and that dictates its appearance and dimensions.

Wrapped Painting (2006) clearly builds upon some of the features of The Diary Project. The work consists of a monochromatically painted strip of canvas that is rolled around a wooden stretcher of approximately the same width. Loose threads are dangling from the sides of the canvas on which the holes, that must once have attached the canvas to a flat surface in order for it to be painted, are still visible. You cannot say for sure that the whole stretch of canvas is in fact painted in the same blue because most of it is invisible. Part of it faces the wall and most of it is hidden under other layers of canvas. In order for the spectator to verify his assumptions he would have to unroll the canvas like a roll of parchment. But in doing so, he would destroy the work, almost like a sacrilege, unveiling what has been deliberately withdrawn from sight. This links the work to the visible/invisible continuum that was also present in The Diary Project and that had already been explored in Encyclopedia: Omission#1 (2004). Encyclopedia: Omission#1 consists of 103 MDF panels collected in five wooden boxes. One of the panels displays a roll of wallpaper with a road painted on it. At the bottom the title of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road is added, complemented with the caption that Perhaps art should be more like wallpaper. The panel was inspired by the anecdote of how Jack Kerouac worked on On the Road. Kerouac is said to have written the original manuscript for the novel in just three weeks on one long roll of paper. The story is recounted by Ann Charters in her introduction to the novel.

A rapid typist, Kerouac hit on the idea of typing nonstop to get the “kickwriting” momentum he wanted. Like the poet Hart Crane, he was convinced that his verbal flow was hampered when he had to change paper at the end of a page. Kerouac taped together twelve-foot-long sheets of paper, trimmed at the left margin so they would fit into his typewriter, and fed them into his machine as a continuous roll. (…) Kerouac started his book in early April 1951. By April 9, he had written thirty-four thousand words. By April 20, eighty-six thousand. On April 27, the book was finished, a roll of paper typed as a single-space paragraph 120 feet long.[2]

Of course Wrapped Painting has no text on it. It is all image and material presence showing how layers of painted canvas are applied on top of each other. Somehow it might be said to resemble a novel rather than a painting because the potential of what is hidden on the next page or layer is very much present. But in fact there is no need to turn the page. Intuitively we know that every page is covered with the same words. Perhaps because of its bluish blankness, Wrapped Painting seems to presents us a chroma key for our imagination and projections. It does so by referring to the historical tradition of painting, of applying layer after layer of paint. The layers of paint, however, have become layers of canvas and instead of transparently building up an image, layer after layer, they hide as much as they show. The object shows how painting has become folded onto itself and how it can hide and reveal things at the same time. »

[1] An Excerpt of McCormick’s video can be found online: http://www.vimeo.com/368367.

[2] Charters, Ann. “Introduction”. in Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. Penguin Books, 1991 [1957]. pp. xix-xx.