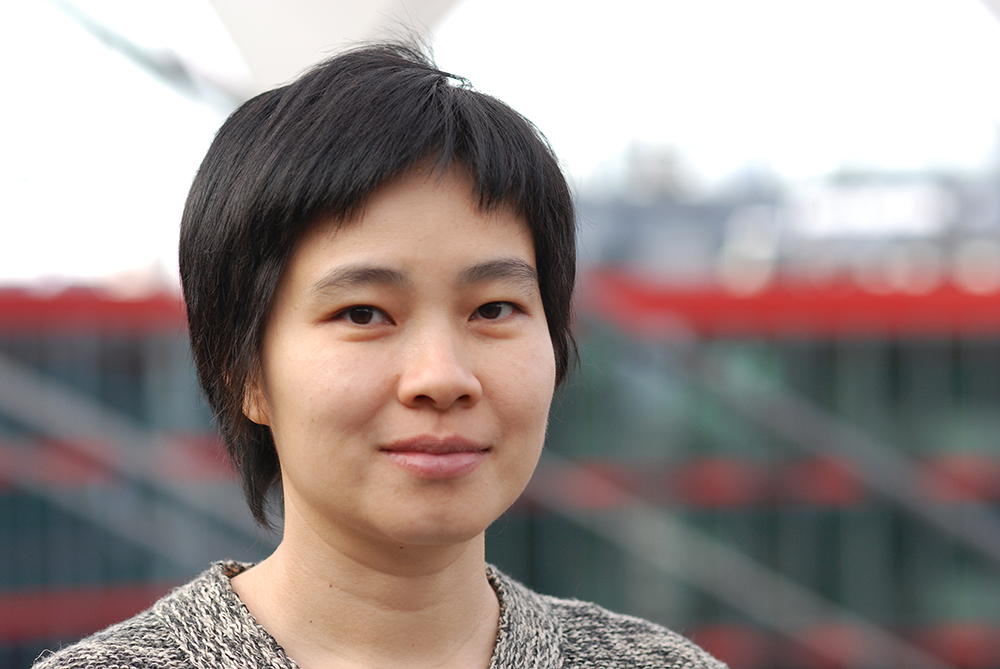

Censors Must Die, Ing K, 2013.

January 29th, 2017. Chinese New Year. In Paris, the traditional festivities which take place in the XIIIth arrondissement are suppressed “for security reason”. Since this summer, before our eyes, Turkey is turning into a dictatorship as fast as the ice cap is melting. As in the 1930s in Europe, should we again see how rapidly the achievements of culture and education can be swept away? This blog is ending as Trumpery is spreading a new storm of chaos, falsification, racism, egoism, self-satisfied ignorance and cruelty all over the world. Since the end of WWII and its promises of reconstruction, how did we regress so quickly? What has to be done, with the weapons of art?

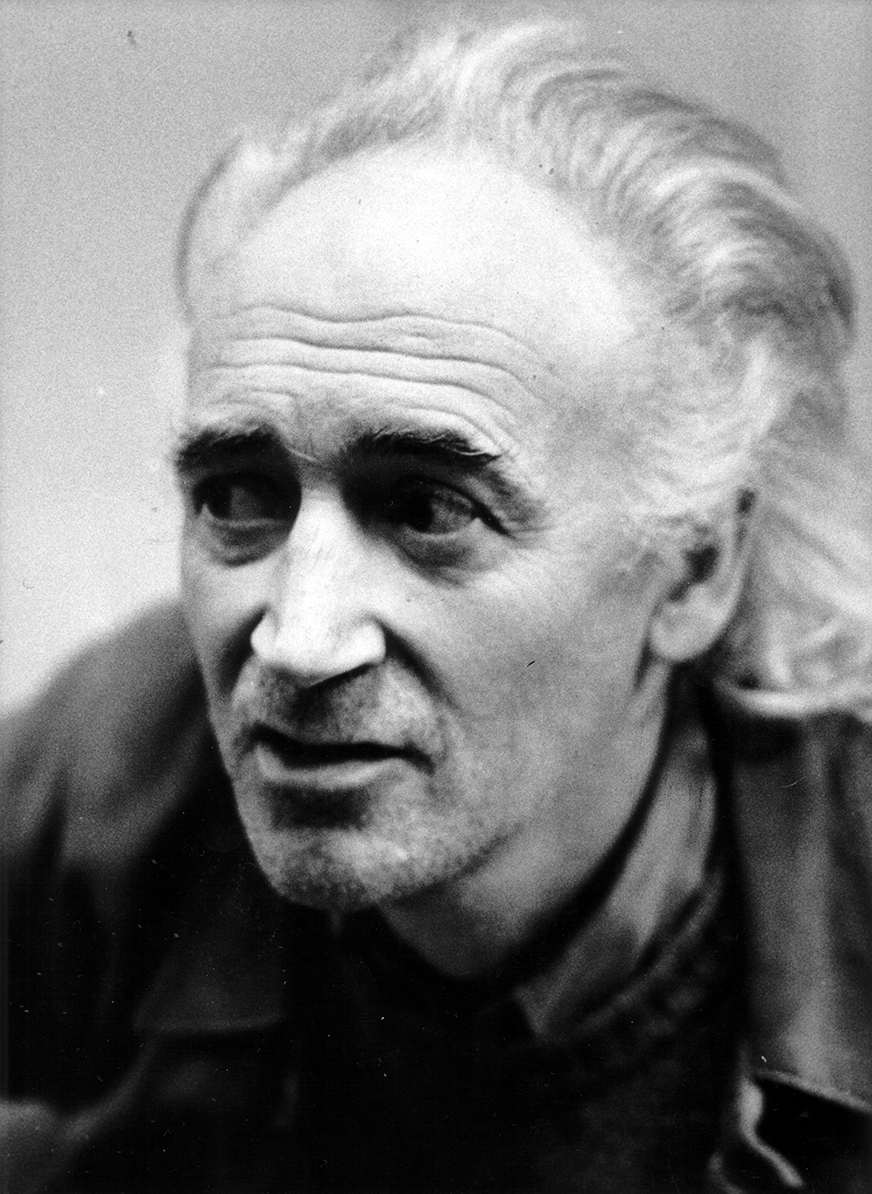

Macbeth, Satan, Death and the author, set photography of Shakespeare Must Die,

Ing K (2013). ©Ing K.

With her usual Witz and energy, the filmmaker Ing K, who for almost 40 years struggles daily against oppression in Thailand, through her blog “Bangkok Love Letter” sends some news and metaphorical principles about censorship and self-censorship.