Cindy Sherman

Museum of Modern Art February 26 — June 11, 2012

Curated by Eva Respini

Francesca Woodman

Guggenheim Museum March 15 — June 13, 2012

Organized by Corey Keller (SF Museum of Modern Art)

Cindy Sherman. Untitled #463. 2007-08. Chromogenic color print, 68 5/8 x 6″ (174.2 x 182.9 cm).

Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York © 2012 Cindy Sherman

I was at the Press Preview for the Francesca Woodman exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum last week, and I was watching her videos with Richard Armstrong, the Museum’s Director. We started talking – reminiscing, really. I explained that I knew Francesca Woodman – long ago, when she was alive, making art. We talked about her friends, who were often my friends; we talked about the scene then, in the late 1970s, and the influences so evident in her work as well as mine. At a certain point, Armstrong looked at me with a bemused expression on his face. “It must be strange,” he said, “to see your life flash before your eyes like this.” Yes, I said. Yes.

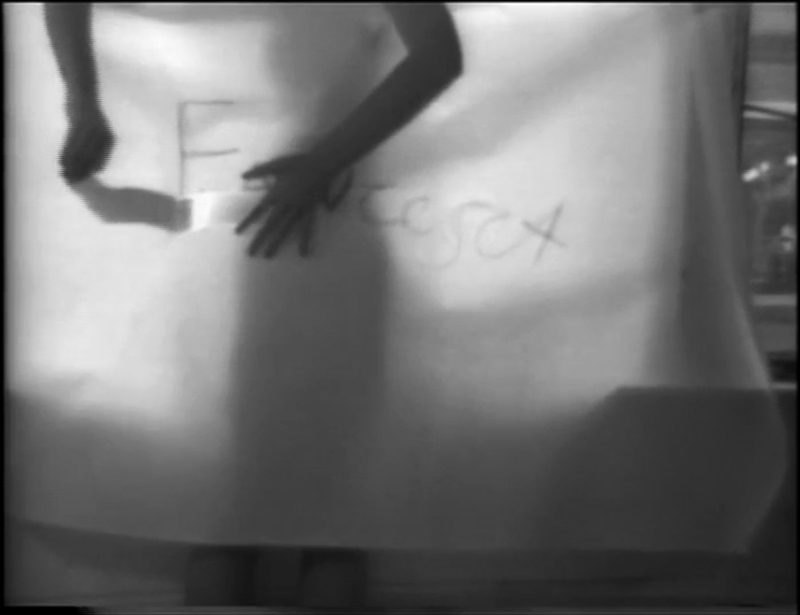

Francesca Woodman Selected Video Works, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976-78

Half-inch black-and-white open reel video transferred to DVD, with sound, 11 min., 34 sec

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

This has been a particularly odd moment, when art and life seem to be doubling back on me. It is obvious from reading some recent criticism, or listening to hushed conversations in the galleries at MOMA, that I am not alone in my current perplexed relationship to Time. Eva Respini’s Cindy Sherman exhibition is a real tour de force; it upends Sherman’s work, removing it from the chronological context of her life and career and going instead for thematic juxtapositions and visual drama. This shock unmoors the images from space and time, and forces viewers to see the work – and its principle sitter – in surprising and unexpected ways. But in spite of its cuts and curlicues, and its refusal to adhere to a master narrative of artistic evolution, the exhibition cannot hide the salient fact that Cindy – like her recent subjects, rich society matrons – has aged in front of our eyes.

Cindy Sherman. Untitled #465. 2008. Chromogenic color print, 63 3/4 x 57 1/4″ (161.9 x 145.4 cm).

Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York © 2012 Cindy Sherman

When I say this I am not speaking offhandedly, noticing wrinkles or bulges or other signs of middle age in pictures that are, of course, so heavily shaped by special effects and make-up. I am speaking instead about a life process: Cindy Sherman is, ultimately, a performance artist, and her self-images move through time as she does. They are connected to her like Peter Pan’s shadow was to him, in a way that, let’s say, Julian Schnabel’s paintings or John Chamberlain’s sculptures are not connected to them. Those rich women of a certain age, holding on to their money and their youth with every ounce of will they have, break my heart. This has nothing to do with feelings of empathy or cruelty that others might attribute to the artist, reactions discussed at length in Johanna Burton’s provocative catalog essay. Those matrons remind me of the passage of time, and so they remind me that Cindy and I have made it to this point — and that Francesca has not.

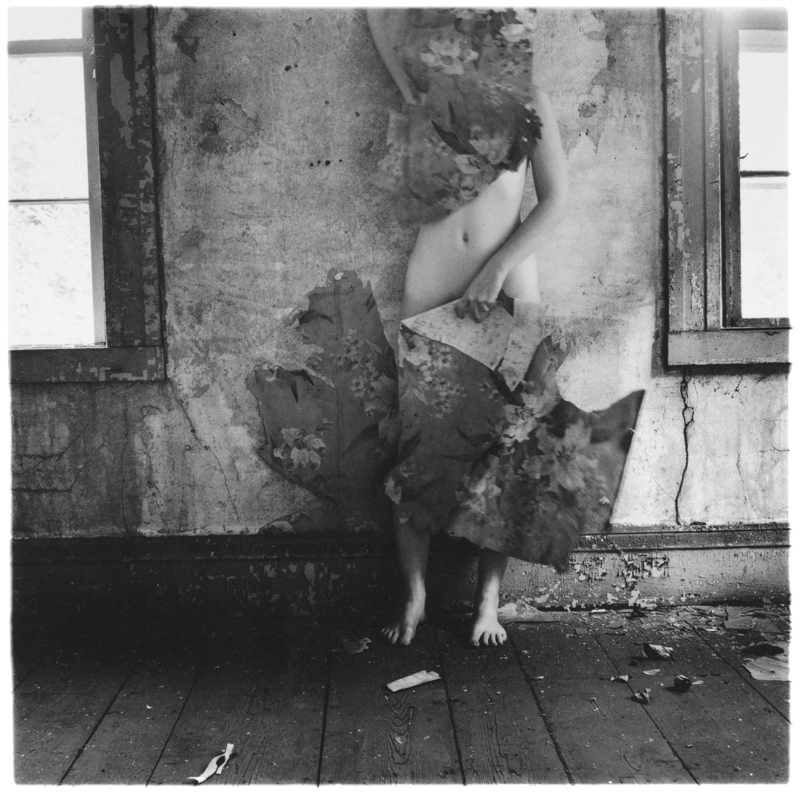

Francesca Woodman House #4, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 Gelatin silver print, 14.6 x 14.6 cm

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman © 2012 George and Betty Woodman

Very girly of me to think this way, isn’t it? This Blog Post is obviously not a high level theoretical discussion, or an objective art historical commentary, eh? No. One of the things that has to happen when we allow works like Sherman’s, like Woodman’s, like Martha Wilson’s and Sanja Ivekovic’s into the mainstream of international art is that we have to adjust the terms of its reception. And we are at the moment facing such a readjustment, now that the first waves of feminist artists lucky enough to make it to their Golden Years are beginning to express their reaction to the ravages and rewards of longevity, maturity and decay. Whether or not these are Cindy’s (or her curator’s) intentions, her retrospective has forced me to see myself in time, and to ask questions about temporality, duration and absence – and what these have to do with, in this case, women’s art.

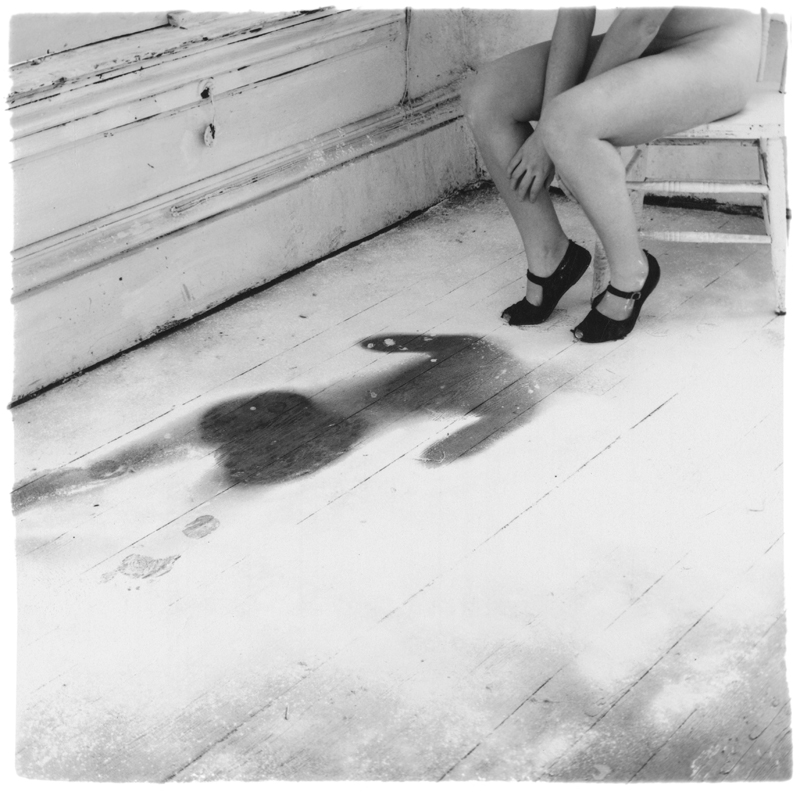

Francesca Woodman Space 2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 Gelatin silver print, 13.7 x 13.3 cm

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman © George and Betty Woodman

Let’s start with Francesca, since she had so little time. Born in 1958, the daughter of well-known and well-connected Manhattan artists, Woodman committed suicide in 1981, when she was 22 years old. What we have, in other words, are photographs she produced before, during and right after she was in college. She had very little time to go beyond that, though the scale of her exhibition makes clear that she worked obsessively and with focus during her passage on the planet. The hoopla surrounding this body of work, the canonization of this young woman as a great and tragic photographic artist, has always been deeply problematic for me – a conundrum not at all dispelled by Keller’s well-organized and informative exhibition. Francesca was very gifted, and beautiful. It’s evident in the pictures that she absorbed lessons from everywhere: from Surrealist artists, from the performance artists and feminists who were her teachers, mentors and friends, from Duane Michals, Deborah Turbeville and Aaron Siskind (whose wonderful show, Spaces, organized at the Rhode Island School of Design around the time when Woodman was a student there, was obviously an influence on her as it has been on me.) Looking at her work, frozen in time as it is, I see the urgency and excitement that marked this particular moment when American art met American photography. And I also see a young woman trying very hard to disappear into eternity.

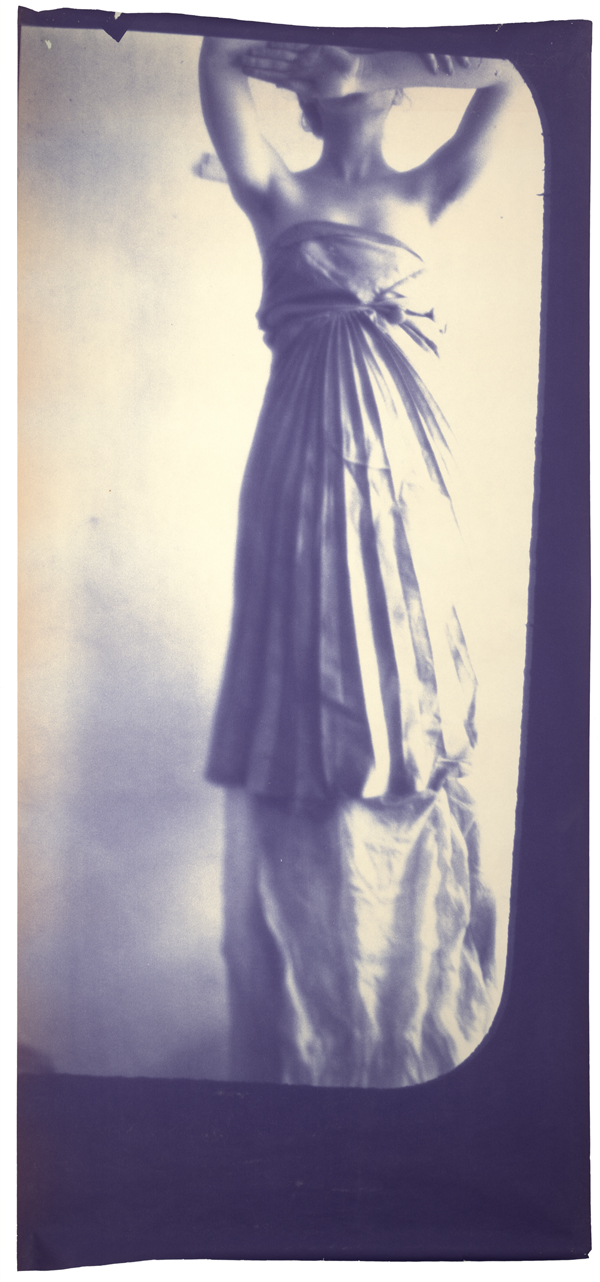

Francesca Woodman Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 Gelatin silver print, 14 x 14.1 cm

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman © George and Betty Woodman

Woodman, like Sherman, specialized in self-portraits, but hers illuminate the modernist moment right before Postmodernism came on the scene, so the comparison is instructive. Romantic, black-and-white, often blurry, Woodman’s images describe a subjectivity that never stopped wiggling – and that could never, somehow, see itself without a mirror or camera’s lens. Jumping, climbing, tracing its outline on the ground, Woodman’s beautiful and usually naked body – with breasts sometimes visualized as angel wings — is hard to grasp, since it is most often disappearing into a blur, a fireplace, a decaying wall or an armoire. There was an article in the New York Times Magazine on March 25 by a young writer named Elisabeth Donnelly, describing her eagerness to purchase a dress from the Mad Men fashion collection at her local Banana Republic store. Obsessed with the popular television show about office and boudoir politics in the 1960s, she is excited to “try on” the accoutrements of femininity that visually defined its historical moment. Donnelly is perplexed by her mother’s pained refusal to perceive these dresses as simple fashion; the older woman sees them as signifiers of her difficult youth, and she refuses to treat stories about the abuse and cruelty suffered by women during this era before the Feminist Movement as entertainment. Francesca Woodman was younger than Donnelly’s Mom, but she was alive during the years of transition between these two generations. These were years when it was hard to pin down what exactly was expected of us, and her art is of that moment. In one of her videos, she writes her name on a large sheet of paper draped between the camera and her nude body. She then proceeds to tear the letters and finally the paper, walking through its constraints and out of the picture altogether. Looking at Woodman’s photographs, seeing that nubile torso and its discontents, I think about Deborah Turbeville’s book Wallflowers and Joan Didion’s novel Play It as It Lays, created around the same time. Awash in a sea of liberated bodies and endless possibilities, all of these women made art about being lost in space.

It is important to understand that a number of Woodman’s photographs, especially those created in Providence, Rhode Island, were initially art school assignments. There is evidence, in late work with which I was unfamiliar, that she might have gotten tired of such self-absorption if she had lived, might have one day ceased to focus on the wiggly subjectivity hidden beneath the curves of her youth. Just the very act of photographing obsessively, of transforming movement into stasis, hot flesh into cool 2-dimensional silver, was this young woman’s bid to leave the world’s disorder and inhabit the looking glass realm of art. Her later, large-scale works moved further in this direction; they began transforming her body into stone. In these she became a caryatid, large and forceful, her youthful limbs no longer personal, translucent and weak. Merging with the Ancients, she left the flesh behind and passed into the immortality of Classical Greece.

Francesca Woodman "Caryatid", New York, 1980 Diazotype, 227.3 x 92.1 cm

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman © 2012 George and Betty Woodman

Premonition of death? I doubt it. But this transformation from individual to icon does in fact curiously lead us to Woodman’s artistic afterlife, and to Cindy Sherman. Francesca died in 1981. Five years later, Ann Gabhart, then director of Wellesley Art Museum, organized an exhibition that travelled to Hunter College and other University museums in the United States, and asked Rosalind Krauss and Abigail Solomon-Godeau to write essays for the slim catalog. Thus began the transmutation of Woodman from vibrant, social and engaged young woman, recently deceased, into a canonized female artist, self-made loner and tragic practitioner whose sole creative forebears were male Surrealists. Conveniently dead, unable to either evolve or talk back, Woodman was transformed into an empty stone caryatid, in this case upholding the pantheon of groundbreaking women artists. Lolita, in a high art context.

The advantage of Corey Keller’s exhibition is that it begins to breathe life back into Woodman’s oeuvre, to reconnect time and evolution and sociability into her brief and productive time on earth. But I remain fascinated by Woodman’s interest in classicism at the end of her life, and her move to create large scale works in which her body transcends rather than expresses subjective concerns. Caryatids were aspects of public art, not private expression. She was, in other words, moving (four years after the Pictures exhibition, around the time Sherman was making the Centerfolds commissioned by Artforum) in the same direction as the Postmodernists.

Installation view: Francesca Woodman, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, March 16–June 13, 2012

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

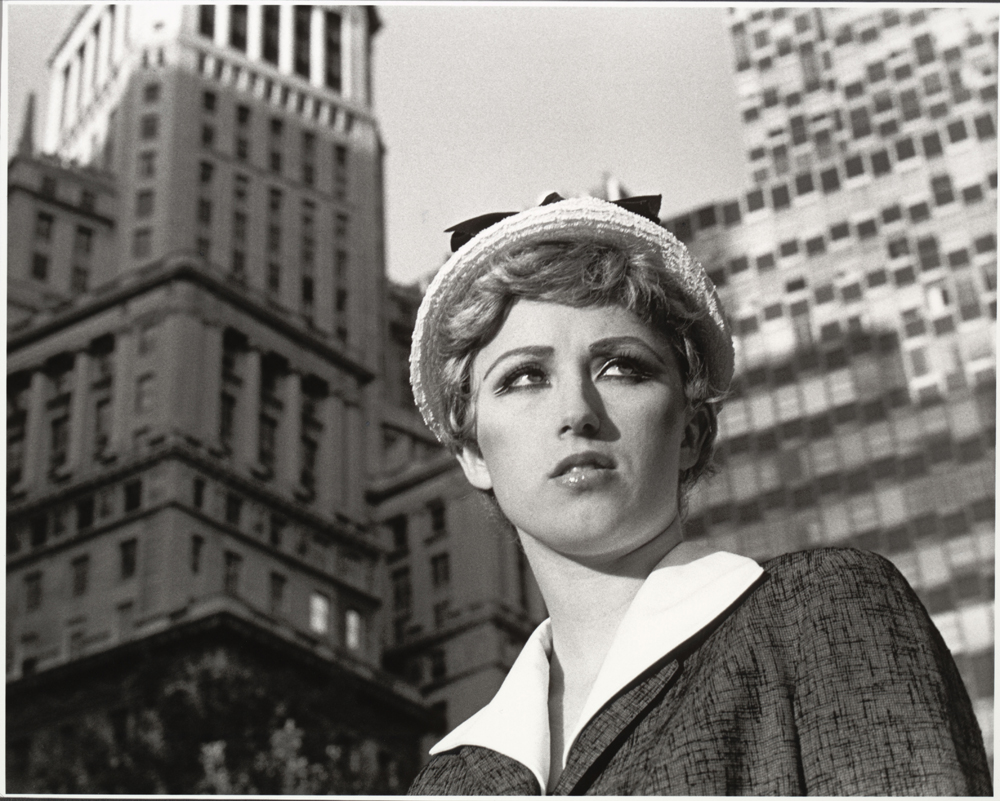

Cindy’s early work, those wonderful film stills presently on view at MOMA, were shocking at the time of their creation precisely because they completely suppressed the personal uncertainties and internal dialogues that were the currency of art in those days. They were not about Sherman’s emotions, but about her desire to transform herself into the icons in our public domain. Stereotypes of women – vulnerable, anxious, frightened, threatened – from the films of our youth, they proclaim that we are not what’s inside us but what we behold. Sherman, of course, grew up in suburban America during the early days of television, the time when mass media images breached the walls of our homes. Moving into the living room and the bedroom, they muddied the boundaries between the public and the private, the here and there, the outside and inside – in the process rewiring, perhaps replacing, those anguished internal dialogues. We are molded into the world of Mad Men, these pictures seems to say, one photo, one television show, one movie at a time.

Cindy Sherman. Untitled Film Still #21. 1978. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 x 9 1/2″ (19.1 x 24.1 cm).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Horace W. Goldsmith Fund

through Robert B. Menschel © 2012 Cindy Sherman

The film stills show Cindy creating and then walking into stage sets of cities, of bars, of domestic environments. A housewife, a nurse, a student, a hitchhiker: she tried on roles that were already there, already recognizable. Through about the year 2000, in fact, Sherman most often embodied iconic figures, male and female, omnipresent in the visual bouillabaisse of our media culture: sorcerers, fashion plates, monsters, Art History paintings, Mrs. Santa Claus. As she moved into her 50s, though, with the photographs of Los Angeles types, this focus on icons began to erode. Sherman left the silver screen and stepped down into the far murkier landscapes of living beings, where those that you behold are not archetypes but your friends and neighbors. Which of course brought both her, and now me, back into Time.

Cindy Sherman. Untitled #466. 2008. Chromogenic color print, 8′ 6″ x 70″ (259.1 x 177.8 cm).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of

Robert B. Menschel in honor of Jerry I. Speyer. © 2012 Cindy Sherman

I became aware of this while viewing the exhibition. I was staring at one of her earliest color works, where she, posing as a young urban ingénue, was smilingly lifting a glass to an unseen entourage at a bar. In those days (c. 1980), of course, Sherman worked alone in the studio; no one was there, and the environment was often a slide projected behind her on the wall. But what struck me, in fact, was her joyful youth, and the ease with which she fit into this role. This scenario was familiar, and welcoming; like Elisabeth Donnelly, she embraced the narrative of her fantasy alter ego with grace and confidence. It was, after all, only play-acting, and even the most anxious, vulnerable, heartbroken or lonely ladies were part of the dream of womanhood in those days.

Cindy Sherman. Untitled #131. 1983. Chromogenic color print, 7′ 10 3/4″ x 45 1/4″ (240.7 x 114.9 cm).

Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York © 2012 Cindy Sherman

That ease, that grace is gone from the latest works, which is one of the reasons that they are so hard to bear. Often made in Photoshop with digitized or painted backdrops, they create visages and environments for the sitters (usually, of course, Sherman herself) that are, quite simply, out of joint. Holding on desperately to their youthful faces and bodies, the only positive archetypes our youth-oriented society offers them, these life-sized women are most often seen against backgrounds that also look toward the past: cloisters, walled gardens and courtyards, ornate salons. This temporal orientation marks a very important difference between Sherman’s early and later works. Her early ingénues (like Elisabeth Donnelly) were propelling themselves into a future, inhabiting their fantasies without thinking much about the consequences. The visual models embodied by the society matrons, on the other hand, do not flow forward in life and time; retro here means more than an attraction to 50s fashion. Like Donnelly’s Mom, Sherman’s subjects cannot don styles that function as empty signifiers, ready to be filled with dreams. The choices available to them are engorged with memories, echoes of an ancien régime of flesh and spirit and culture inhabited not with grace but reluctantly, with strain. The strange disjunctions between figure and ground in these photographs makes it seem as if each of these living women is in the process of ossifying, metamorphosing from a living being into a monument – a caryatid, perhaps? Like their Classical forebears, these matrons are large, full-bodied and strong; they dominate the picture plane with their intense psychological presence. But most important, and ultimately more to the point: however poignant or complacent, desperate or arrogant they may appear, these mature women – like Cindy and me – are still here.

Shelley Rice

© Shelley Rice, 2012

Further Reading and Links

Shelley Rice (ed.), Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, Cindy Sherman (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1999)

Elisabeth Donnelly, “Mad Women,” New York Times Magazine, March 25, 2012, p.62