Invited Blogger: Rob Perrée, Editor, Kunstbeeld Magazine, Amsterdam

Review of the 76th Whitney Biennial, The Whitney Museum of American Art, March 1 through May 27, 2012. Organized by Elisabeth Sussman and Jay Sanders, with Thomas Beard and Ed Halter.

Wu Tsang (b. 1982), Production still from WILDNESS, 2012 (in progress). High-definition video, color, sound. © Wu Tsang; courtesy the artist

I invited my friend Rob Perrée, in New York for this month’s exhibitions and fairs, to write his assessments of the Whitney Biennial for this Blog. Though he saw some good works and some positive aspects of the exhibition, in general Perrée feels that the incorporation of time-based arts – performance, film, video – into the fabric of the show weakens the curators’ statement. This opinion is not shared by our colleague Roberta Smith, whose review in the New York Times Weekend Arts section on Friday, March 2 found this aspect of the exhibition challenging and exciting. My own feelings, I must admit, are closer to Smith’s than Perrée’s; but I’m delighted that they both highlighted certain stand-out works – Werner Herzog’s, Forrest Bess’ and Wu Tsang’s – that particularly struck a chord with me. And, perhaps not surprisingly, both critics noticed that one of the strengths of this year’s exhibition is that it is not top heavy with famous, “blue chip” (most often male) artists, who have tended to steal the spotlight from younger, lesser known participants in some recent shows. Instead, famous artists are there, but discretely, integrated into the installation with no special fanfare. Marsden Hartley has a few lesser-known paintings scattered throughout the show, and Warhol has a terrific but very low-key photomontage of a bicyclist tucked away on a side wall. This allows the exhibition to be less of a circus and more of a learning experience, offering invaluable information about the intergenerational nature of artistic creation in the United States. When Garry Winogrand shares the space with a young talent like LaToya Ruby Frazier, who contributed a documentary project about economic crises in New Jersey, we learn not only about “stars” but also about those who follow in (or resist) their footsteps.

Shelley Rice (© 2012)

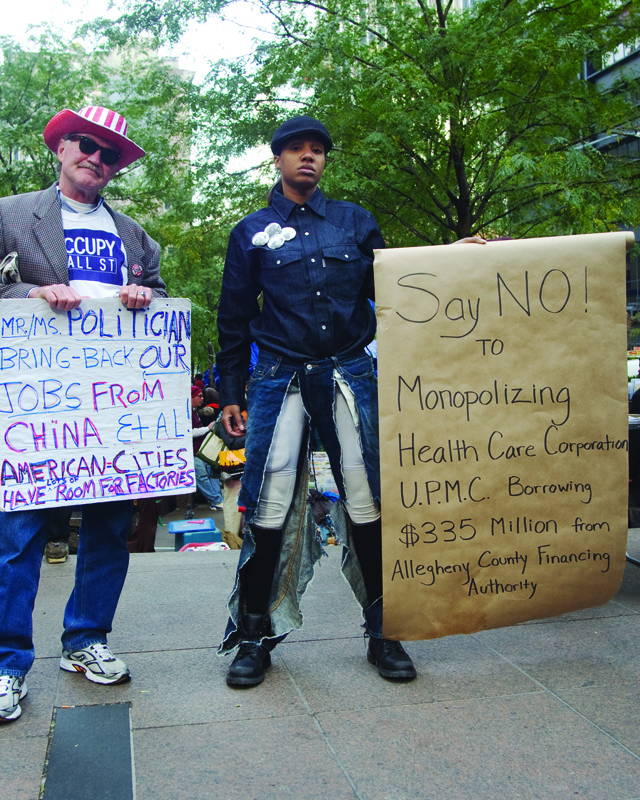

LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982), Corporate Exploitation and Economic Inequality!, 2011. Digital photograph, dimensions variable. © LaToya Ruby Frazier; courtesy the artist. Photograph by Abigail DeVille

A GOOD CONCEPT WORKS OUT BADLY

By Rob Perrée (© 2012)

The curators of the 76th Whitney Biennial have set themselves a very challenging task, to organize an exhibition based on an inspiring concept. They want to redefine what an artist can be at this moment, and they do this in two key ways within the show. In the first place they emphasize the connecting points between the visual arts, performance, dance, music and film. Secondly, they highlight the resonances between artists. Not only did they invite a few artists to curate parts of the biennial, but and they also included a number of people who use, or who quote the work of, other artists within their own expressions.

This second part of the exhibition concept works out well. Robert Gober, among others, curated an interesting small show of the rather unknown Texas artist Forrest Bess (1911-1971). His visionary abstract paintings are based on the theory that male and female can be united in one body, and the display includes notebooks, sketches and photos from his personal surgeries. Richard Hawkins uses fragments of reproductions of the work of other artists in his collages. Nicole Eisenman quotes many colleagues in her 45 expressionistic portraits on view — among them Marsden Hartley, present elsewhere in the show with a beautiful portrait from 1940.

With the exception of a stunning film installation by Werner Herzog, which combines landscape images by the 17th century Dutch artist Hercules Seghers and the music of contemporary composer Ernst Reijseger, in such a way that sound and image become one, the first part of the concept fails completely. This is due to highly underestimated practical circumstances. Film, performance, dance and music are time-based disciplines. They need to be presented at certain times and in certain locations. To make that happen, the curators earmarked the 4th floor as a theatrical setting for the various dancers and performers taking part in the show, and they organized a film/video program in a separate room. The consequence is that the 4th floor is an empty, useless space (at least as far as the more traditional, static visual arts are concerned) for 80% of the exhibition time. The film program, in itself very diverse and interesting, relates in many different ways to the artworks on view and has, for that reason, a comparable problem. The objects in the exhibition can be seen every day, but the viewer can only watch that special, related film or video one month later. However wonderful the program connections may seem on paper, the average visitor will never experience many of them.

There is another side effect. Because all the works are so connected, and need each other in a way, the exhibition itself is not strong enough to ‘live’ on its own. There are good visual images and objects presented, but also weaker ones. They depend on their relationship with the time-based works within the context of the show. When the viewer cannot see them on the same day, they lose ground. And the overall exhibition loses quality.

To end on a more positive note, it is refreshing that the curators of this year’s Whitney Biennial did not go overboard for big names and big works. Young, old, known, unknown, deceased or alive, there is no difference in the way the participants are presented or treated in the show. That is a relief. The overblown Jeff Koonses and Anish Kapoors are already everywhere to be seen.

Rob Perrée

Editor of Kunstbeeld Magazine

Amsterdam

March 1, 2012.

External Links:

Roberta Smith Article

Slide Show