![Unidentified Photographer, [Part of the crowd near the Drill Hall on the opening day of the Treason Trial], December 19, 1956. Times Media Collection, Museum Africa, Johannesburg.](../../../../files/2012/10/1.-UP_Drill-Hall.jpg)

Unidentified Photographer, [Part of the crowd near the Drill Hall on the opening day of the Treason Trial], December 19, 1956. Times Media Collection, Museum Africa, Johannesburg.

We must return to the point from which we started: not a return to the longing for origins, to some immutable state of Being, but a return to the point of entanglement…

Edouard Glissant, “The Known, the Uncertain”

This Glissant quote makes an appearance in Sarah Nuttall’s superb book Entanglements, an examination of contemporary art and literature in South Africa. The blurb on the book jacket fittingly describes Nuttall’s text as an “exploration of post-apartheid South African life worlds.” Committed to illuminating the complex strands of difference and sameness, violence, victimhood and resistance entangling all of her fellow citizens in their web, the author explores a rocky terrain of communication, misunderstanding and mutuality that reveals itself even to transient visitors of this intensely creative nation. My own 2009 visit to South Africa – thanks to an invitation from the Roger Ballen Foundation – was, I must admit, one of the high points of my intellectual life. While participating in a two-day seminar at Wits University with artists, curators, critics and intellectuals from Jo’burg and Cape Town, I was privileged to enter into a profound exchange about the nature and responsibilities of culture. Engaging in an open-ended, dynamic and rich dialogue committed to “returning to the point of entanglement,” the participants were intent on forging an artistic and political future not framed by what Nuttall calls a “persistent apartheid optic.”

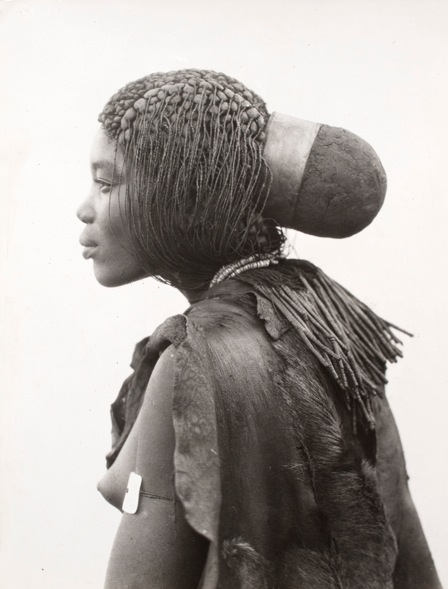

This was, and is, a tall order, and a continuing quest. I’m happy to report that another stage in the ongoing discussion is taking place right now in New York City, in the form of two major exhibitions at the Walther Collection and the International Center of Photography. As I mentioned, when visiting Johannesburg I was grateful to participate in a workshop with people who, while living in a social and political environment that continues to be impossibly difficult, try every day to confront and express their problems directly, head on, instead of relying on “persistent optics” or tired ideologies. The complexity of approach that arises from such an intense commitment is evident in both exhibits, albeit in different ways. Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, curated by Tamar Garb for the Walther Collection, will ultimately be a three part show. On view now, in Part One, are works by Santu Mofokeng and A.M. Duggan-Cronin. Garb sees the African archive as “a contested compilation and collection of artifacts and representations that have accrued over time, and that are open to scrutiny and examination by a new generation of artists and viewers for whom the colonial orthodoxies and truisms that led to its creation are no longer operative or true.” The “contested” part of this assertion becomes clear in the juxtaposition of these two projects, as well as these two exhibitions. A.M. Duggan-Cronin’s Bantu Tribes of South Africa, an 11-volume study published between 1928 and 1954, visualizes an ethnographic vision of indigenous tribes, frozen in an “immutable state of Being” in traditional costumes and ennobled poses in barren and empty landscapes. Hovering somewhere between proud African types and demeaning stereotypes of aboriginal people (depending on your point of view), these Bantu tribes were presented by Duggan-Cronin as representative of an authentic and timeless Africa even as the political struggle for and against apartheid wracked the urban centers of the nation – a struggle extensively described in The Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, curated by Okwui Enwezor with Rory Bester, on display concurrently at ICP.

In other words, two distinct South African temporalities are on view in New York: the one, the stasis of the noble black savage who exists in an eternally retrospective state and the other, the quick tempo of enraged and embattled denizens trapped in a modern bureaucratic state that systematically dismantled their human rights after 1948. But even within the Walther exhibition alone, the definition and depiction of what it means to be an African is “at stake,” as Marta Gili would say. Sharing the space with Duggan-Cronin’s project is Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album: Look at Me, created as a slide show in 1997 (and shown recently at the Jeu de Paume as part of his retrospective exhibition). The pictures (shown in 3 versions: as slides, as the silver gelatin exhibition prints Mofokeng produced from the deteriorating originals, a few of which are also in the gallery) are part of the artist’s personal collection, salvaged from the albums and drawing rooms of neighbors and acquaintances and researched to identify sitters who posed for studio photographers between 1890 and 1950. Co-extensive with Duggan-Cronin’s project (as well as the early days of apartheid), these pictures represent the original studio portraits commissioned, paid for and preserved by Africans who envisioned their ideal selves in modern European-style dress and fancy hats.

Santu Mofokeng, “The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890-1950,” 1997 (Unidentified photographer, South Africa, early twentieth century) © Santu Mofokeng / Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

My colleague Dr. Jennifer Bajorek, who has contributed to this blog and who lectured in conjunction with the exhibition, told her audience that when Mofokeng showed his personal works (black and white documentary pictures describing township life, religion and land, some of which are simultaneously on view at ICP), his subjects did not like them at all. He began collecting The Black Photo Album pictures in order to discover what types of images his neighbors in fact preferred, and thereafter only exhibited his own photographs interspersed with ones that had been commissioned by people in his community. The differences in the depictions are obvious, of course, but so are the time warps built into the project. Multiple temporalities converge when the records of the original sittings (represented by the faded original prints) jostle with the contemporary vision of an artist interrogating the meaning of his forebears’ photographic experience. Unmoored from personal albums and sequenced within the narrative of Mofokeng’s slide show, the portraits are interspersed with his queries and contestations: “Are these images evidence of mental colonization or did they serve to challenge prevailing images of “The African” in the western world?” is one of them. Of course there is no answer to this question, the pictures represent neither and both and the question floats into an existential void. This is the complexity – and irresolution – of entanglement. When the viewer understands that the photographs describe distinct, sometimes contradictory “life worlds” co-existing within the same historical time and space, he or she begins to comprehend the hall of mirrors that is South Africa today.

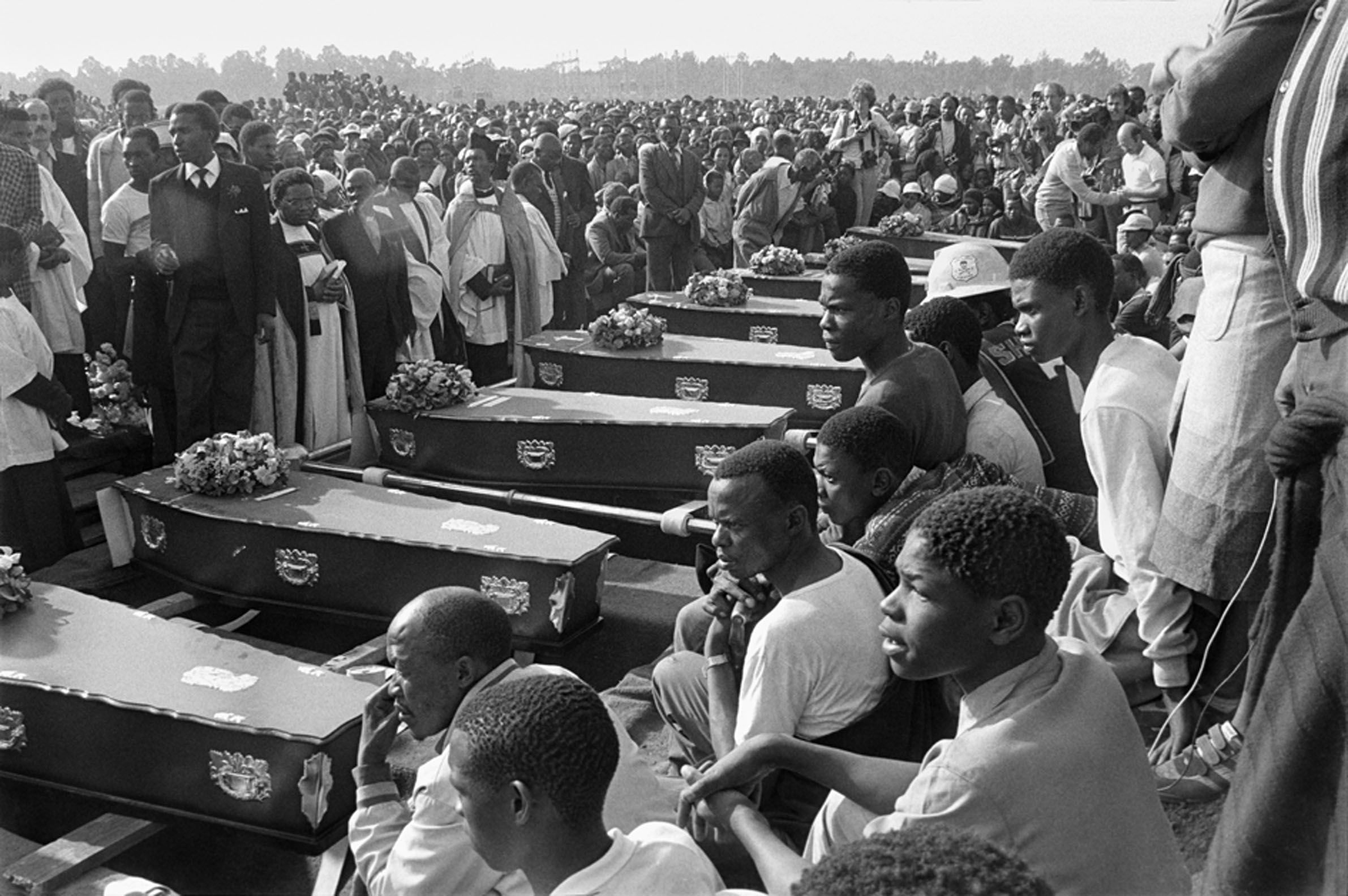

The same dense interactions are evident in The Rise and Fall of Apartheid, although that exhibition gives them a completely different spin. Whereas Distance and Desire is spare and focused on two extended projects, Enwezor and Bester have organized an enormous exhibition with a cast of thousands. Though no one agreed on the precise number of pictures on the walls at the Press Preview, there are at least 500 photographs, which are accompanied by magazines, videos and “overtime” information available on computers in the galleries. At the Preview, Enwezor explained his interest, and excess, by explaining: “We’ve all looked at enough images of D-Day, I wanted people to see something else that was going on around the same time.” Central to the organization of the show is the theme of bureaucracy: the ways in which this horrific system of government was “normalized” within the society through laws, paper trails, housing, transportation and entitlements. Photographic evidence describes how populations forced to live in this increasingly oppressive nightmare internalized (or not) their roles — and developed methods for either maintaining the status quo or fighting back.

Gille de Vlieg, Coffins at the mass funeral held in KwaThema, Gauteng, July 23, 1985. © Gille de Vlieg.

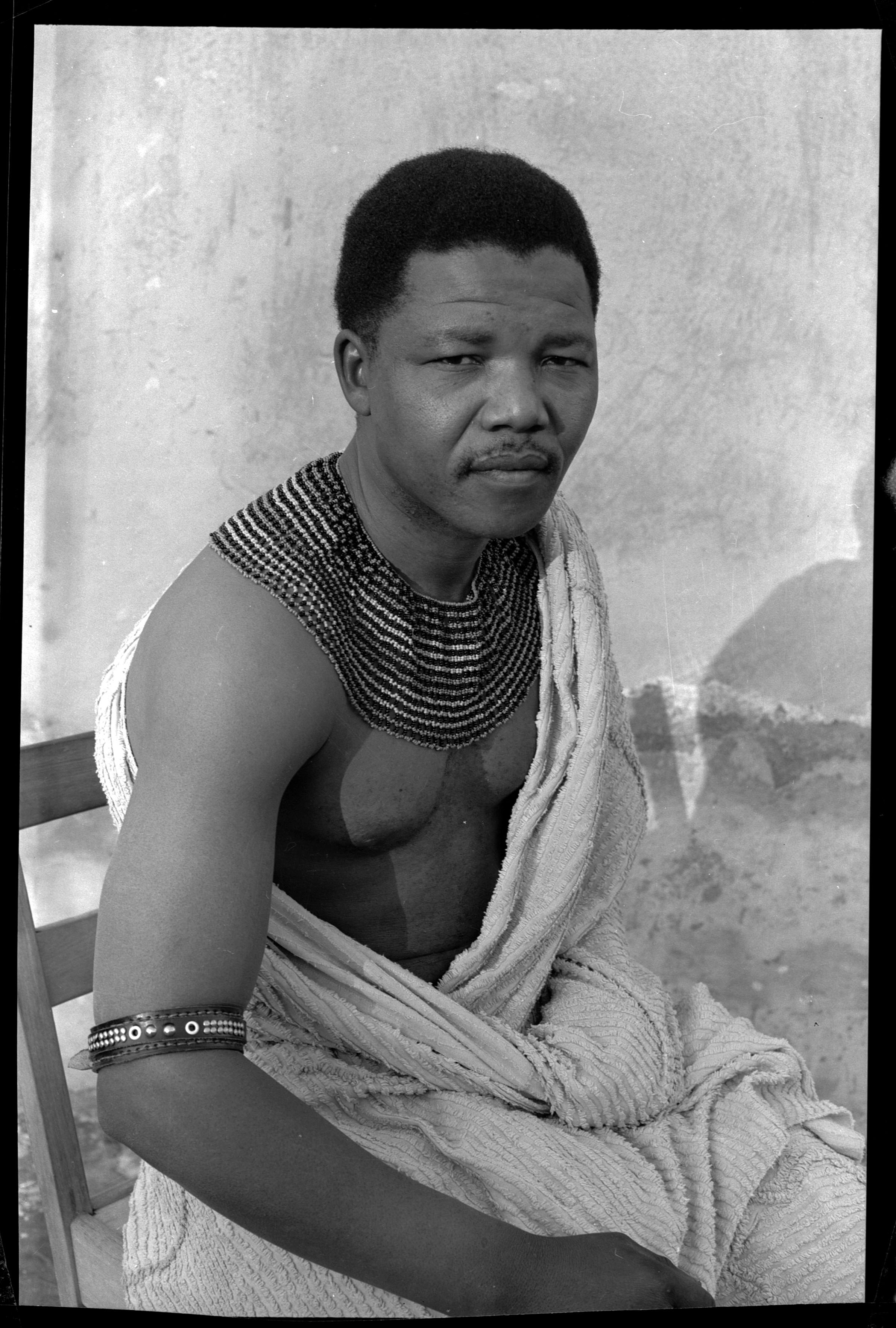

The show is divided into two parts. On the upper level of the museum, the viewer can follow the history of apartheid from 1948 (with the victory of the Afrikaner National Party) until 1994 (the rise of Nelson Mandela). Here we see many, mostly black-and-white documentary photos, accompanied by texts and time lines as well as videos and magazines. The vast majority of the pictures were taken by South African photographers like Peter Magubane, Jurgen Schadeberg and Ernest Cole, but there are also some by outsiders like Margaret Bourke-White and Dan Wiener. The downstairs space focuses mainly on artistic expression, on the responses of creative image-makers to this system of injustice. On display are works by South Africans like Sue Williamson, Jo Ractliffe, Guy Tillim, William Kentridge, David Goldblatt and the collective Afrapix, as well as contributions by foreign supporters like Adrian Piper and Hans Haacke. One of the major premises of the exhibition is that during this historical period, photography was deliberately transformed by its practitioners into an active social instrument. So the duality of the exhibition, its highlighting of both documentary description and artistic interpretation (with lots of links and overlaps between them), is designed to emphasize the multifaceted usage of visual media during an intense period of political struggle.

Eli Weinberg, Nelson Mandela portrait wearing traditional beads and a bed spread. Hiding out from the police during his period as the “black pimpernel,” 1961. Courtesy of IDAFSA.

Another level of intricacy, however, is evident in the choice of subjects covered in the show. Enwezor has made no secret over the years of his disdain for the “persistent optic” of Afro-pessimism: the media’s insistence on seeing the continent and its inhabitants as unmitigated disasters, mired only in violence, poverty and corruption. This exhibition gives a much more nuanced picture of daily life under apartheid, and both blacks and whites are visualized in multiple ways that are not exclusively political. Along with documentary records of government meetings and political figures, protests, violent encounters and hardship, there are pictures of everyday life in both the African and the Afrikaner communities: living conditions, education, religion, parties, music (Miriam Makeba!) and magazines like Drum. Though separate within the context of the show (and the apartheid system), these social manifestations have an equivalent weight here. Their presence does not allow any South African, black or white, to become “stuck” in the political stereotype of victim or aggressor. From Nelson Mandela and the thrill of victory in the 1990s, to the disappointment of the current social malaises and divides expressed by young photographers, we are left not with a fairy tale but with a complicated evolution of many intertwined histories: their triumphs and failures, their possibilities and disappointments as well as their aftershocks and legacies.

Life Worlds will be the last article in my series for the Jeu de Paume. As I said during the video interview posted in the museum’s online magazine, I accepted Marta Gili’s challenge in order to revitalize the language of my contemporary responses to global art. During my travels, I’ve met no people more committed to the complexities of this language than South Africans. As I say goodbye to the Blog and its readers, I am pleased that these artists and writers are front and center. My hat is off to them for all they’ve taught me – and all they continue to teach me in exhibitions like these, enriched with insight about every “entangled” contemporary society wrestling with difficult questions that have few, if any, easy answers.

© Shelley Rice 2012

By the way, after publishing this Post I received at least five phone calls and letters suggesting that I see the movie “Searching for Sugarman.” My friends and students were right: don’t miss it. The story — about a Mexican-American singer unknown in my country and a rock star in South Africa for decades — is incredible.