The British photographer Chris Killip made the decision to begin both his exhibition What Happened: Great Britain 1970-1990 at Le Bal in Paris (organized with the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany by curator Ute Eskildsen) and his book Arbeit/Work (Steidl, 2012) with the following statement:

One night in 1994 my friend John Clifford, who owned the best bar in Cambridge, took me into the middle of Boston to where the civic center and other administrative buildings now stand. These buildings were built in the 1960s on top of the tough working class district of Scully Square, where John and his brothers were born and raised. John pointed out to me streets that no longer existed, telling me who had lived where and in which house. Who had died in Vietnam, who had worked for the mob, who had gone to prison or ended up in politics. When I interrupted his narrative to tell him how great it was that he was telling me the history of this place, he spun round, gripped me by the throat and pushed me against the wall. With his raised fist clenched he said, “I don’t know nothing about no fucking history, I’m just telling you what happened.”

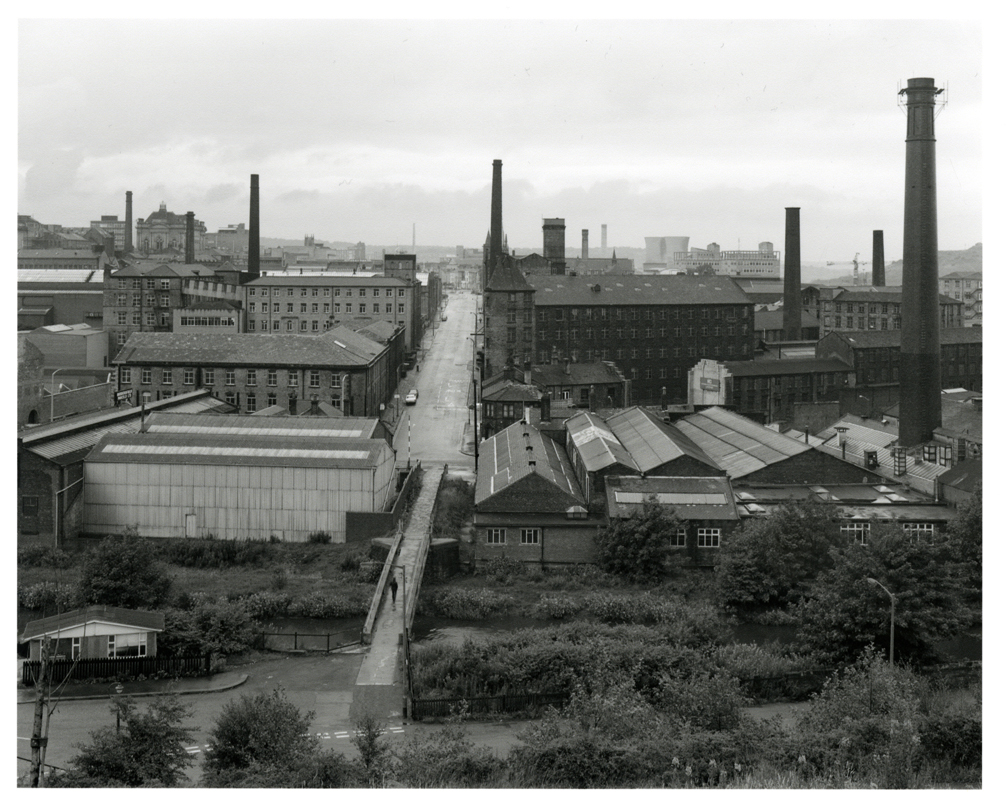

After seeing the exhibition, and watching the accompanying 12 minute film from 1976, A Girl Chewing Gum by John Smith, the viewer begins to understand the relevance of this powerful anecdote. Personally, I had the sense that the entire show was a kind of personal struggle with meaning – in both art and life. Killip’s documentary photographs, about inhabitants, workers and others in Britain on the Isle of Man, Bury St. Edmunds, Huddersfield, Lynemouth and areas of the Northwest of England, portray, as David Campany wrote, people “exiled within themselves, incapable of finding their moorings, merging into a collective drift” as they are increasingly disenfranchised by the changing economic circumstances of a rapidly de-industrializing nation. The meaning of these peoples’ lives within the national economy takes a hit right in front of our eyes, but so does the concept of photography that allows an artist to interpret the conditions and destinies of others. This show and book are as much about Killip’s attempts to define his relationship with his subjects as it is about the subjects themselves.

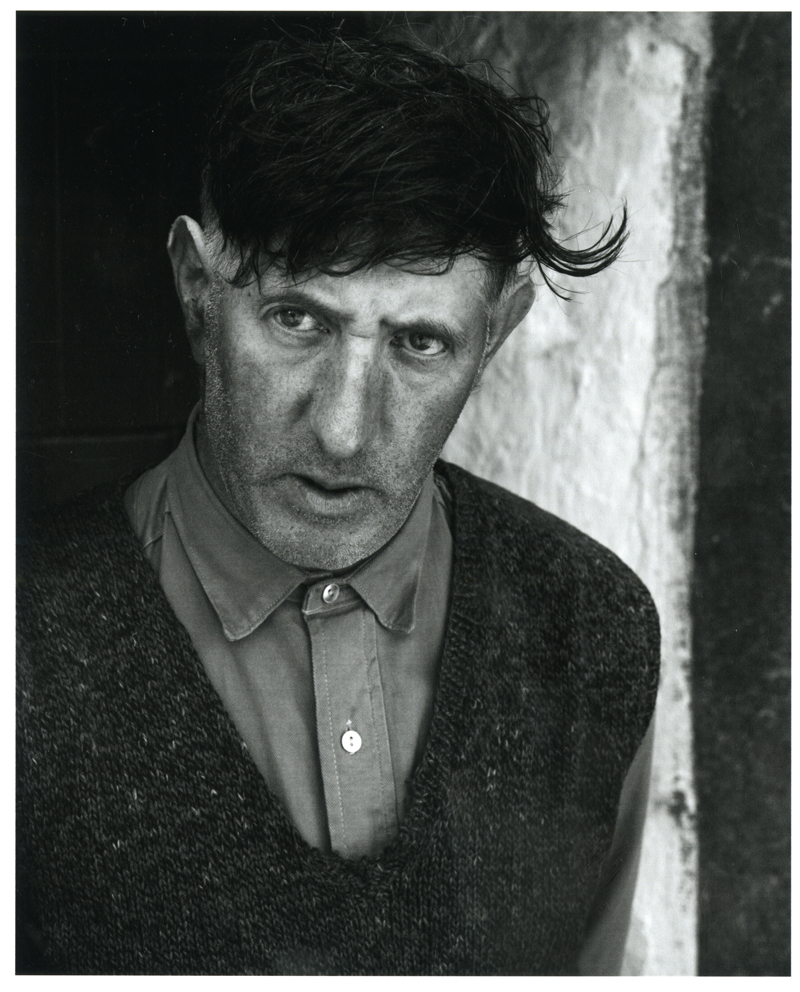

It is useful to understand that Killip’s influences include Paul Strand and August Sander, as well as Bill Brandt, Robert Frank and (especially, from my perspective) Walker Evans. Like Killip, Evans walked a thin and often tense line between the socially prescribed meanings of things and those in which he believed. Campany makes a case that Killip’s work has never been “of its time,” and in a sense this connects him deeply to his forbear. Working in America in the 1930s, where everyone “knew” how to define and pity a victim of poverty, Evans struggled to transcend the popularly accepted, simplistic and ultimately degrading definitions of those struck hard by the Depression. Committed to treating all humans, rich or poor, as complex beings and emotional equals, adamant that he would never allow political ideologies or economic hierarchies to stand between him and his subjects, he entered into continual conflict in his job at the Farm Security Administration because his superiors felt his work was “not political enough.”

Looking at the muscular black and white images in What Happened, it is easy to see Killip fighting the same fight, but this time his invisible adversaries were (are) the proponents of “Concerned Photography” in (and after) the 1970s. Those were the years when the International Center of Photography opened its doors, and the years when the liberal print media (and it was liberal sometimes in those days!) expected photographers to understand and to fight for the poor or for those disenfranchised by race, creed or religion. Nowadays, when every writer can be considered profound by adding “atrocity,” “violence” or “trauma” to the title of some academic text, and every photographer can become a politically correct activist by (once again) defining and visualizing victims, Chris Killip is trying to look clearly, respectfully and without prejudice at the lives of those who are struggling to survive a shifting and often merciless economy. “To the people in these photographs I am superfluous,” he wrote in 1988 in In Flagrante. He refuses to see himself as anyone’s savior, or anyone’s judge; the only activism he admits is his own aspiration to understand and record the life around him. Given the trendiness of political correctness in the theory and practice of photography in the USA (where Killip teaches at Harvard), it is easy to see that he too is shadow boxing the adversary of popular stereotypes and preconceptions, both human and photographic. It took a long time (around 30 years) for anyone to acknowledge that Walker Evans had anything important to say, about the Depression, America and the impact of money and machines on people’s lives.

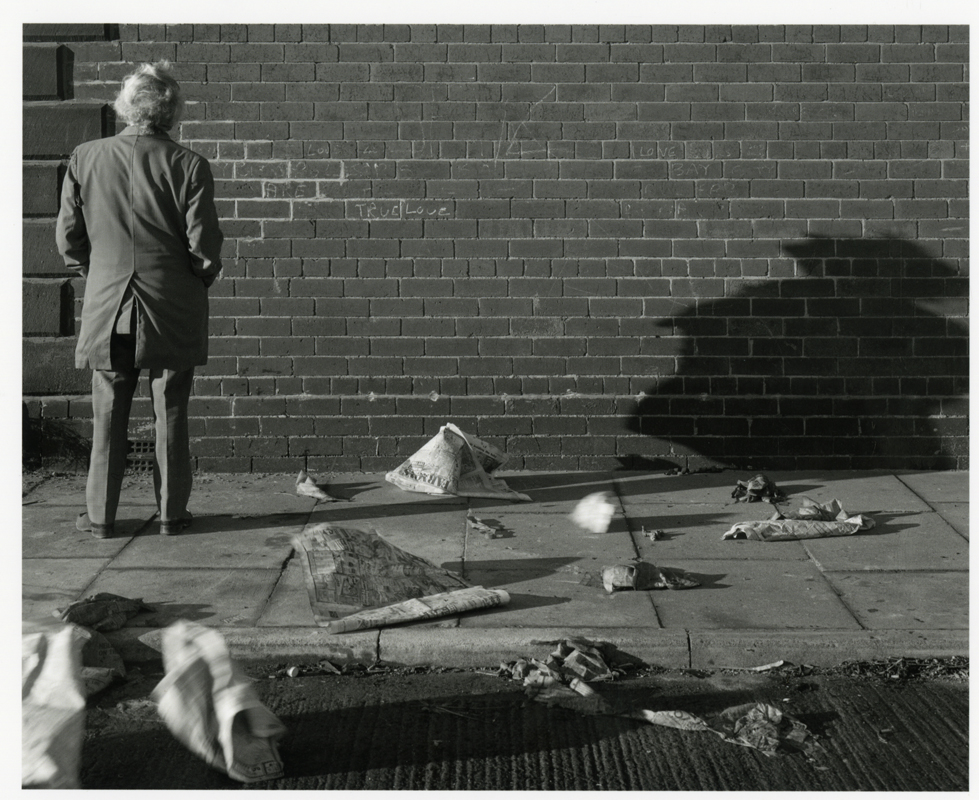

One of the first things to notice is that Killip, like Sander and Evans before him, has made the decision to shift the focus of his photographs away from the individual and toward a more socially contextual approach to human subjectivity. His early work, on the Isle of Man, consists mainly of portraits, with a strong Strand influence, of people who in the 1970s worked in traditional ways in occupations and on territories long considered to be their birthright. The instability of the economic context, the massive shifts in ways of working and economic possibilities and liabilities, begins to impact on the solidity of this long established situation, and the pictures continually emphasize the malaise of sitters trying to position themselves within a strange new environment. A man, standing to the left with his back to the camera, seems flimsy enough to blow away in the wind as he faces a brick wall; although his stance is firm, his white hair flies like the garbage surrounding him on the street, and his body has no more weight than his dark shadow mirroring him on the opposite side of the picture plane. This is an image of a tense detente, literally a stand off as this man tries to remain the still point in a turning world.

In other series, a shipyard that supports a community closes, forcing people to disperse; housing complexes filled with families and children are demolished from one photo to the next. Traditional occupations like fishing, lovingly described, suddenly become anachronisms. Demonstrators, punks and revolutionary slogans make their appearance. Killip’s insistence that people flourish or fail within a social world, that their sense of self is based on moorings that include work, place and community, makes him sensitive to the conditions that create, and degrade, human behaviors. Never perceived as arbitrary or extreme, his subjects are reactive to the times in which their lives are embedded. Their responses are neither programmed, programmatic or predictable. They just are what they are: “what happened.”

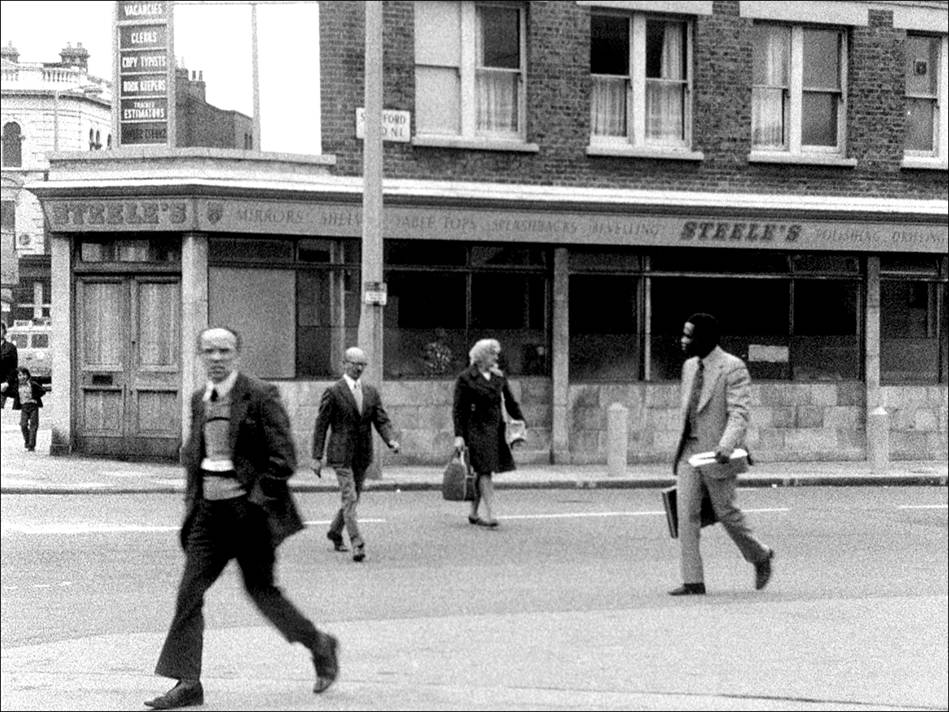

Which leads me to John Smith’s film, The Girl Chewing Gum, a hilarious and smart counterpart to Killip’s searching work. An extended look at an urban corner dominated by a store named Steele’s, this animated black and white street photograph is narrated in such a way that the questions of meaning discussed above become central to the activities of the most banal English passersby. Alternately acting like a Gregory Crewdson style directorial photographer, a choreographer, a traffic cop, a scholar analyzing the random actions or attributes of anonymous pedestrians or an increasingly bizarre interpreter of the visible (or invisible) evidence (which at the end includes descriptions of a black bird with a nine foot wing span and a man with a helicopter in his pocket), the narrator is constantly intervening in what we see and hear, embellishing documentary records in ways that sometimes establish and more often stretch credibility. The girl chewing gum is elevated to significant iconography in this context; English words when read backward transform into Greek ones, and disembodied pronouncements fly (through electrical lines, of course) between the city and a field with cows 20 kilometers away. This film is the best antidote I’ve ever seen to the pretentious certitude of aesthetic interpretation and academic analysis. Susan Sontag, eat your heart out: I want every student I teach to see John Smith’s master work at least twice before picking up a camera or an art history textbook.

SR

© Shelley Rice, 2012