This is a Post-Card from Paris. I’m sitting in an apartment rented from a friend on the Left Bank and reading yet another book purchased at La Hune. (The French publishing industry anticipates an economic upturn the minute I arrive in town.) This time the book is Anne Sinclair’s 21, rue La Boétie (Bernard Grasset, Paris, 2012), a memoir chronicling her research into the history of her family and especially her grandfather, the famous art dealer Paul Rosenberg. Interweaving family stories with political atrocities and deceptions, Sinclair describes the lives and relationships of gallery artists and the fate of their works under (and after) the Nazi occupation. Rosenberg’s fight to preserve his family, his collection and his business interests under impossible circumstances is set against personal stories of war, exile, disappointment and love. Sinclair is a clear, impassioned writer and an experienced journalist, so her cautionary tales of prejudice, cruelty and deceit keep wiggling out of the past tense and surfacing into the murky political waters of the present.

A historian of modern art first and foremost, I am of course interested in the subject of Sinclair’s book, especially since Rosenberg’s influence as an art dealer — of Picasso, Braque and Matisse, among others — spanned two continents and substantially impacted taste, the market and collections in the United States. A champion of the continuity between the past and the present, historical masters and the avant-garde, he fought to establish contemporary art in the highest precincts of American culture. His presence in New York after 1940, of course, was not simply a life style choice, but an imperative dictated by the murderous anti-Semitism of the era. This same imperative dictated that Sinclair would be born of French parents not in Paris but in the Big Apple, a few years after the end of the war and a few years before me.

My family arrived at Ellis Island from Europe — Eastern Europe, mainly Romania it seems — a long time ago (in American terms, which means the 19th century). All four of my grandparents were born in the United States, making me the Jewish equivalent of a Native American, or a Daughter of the American Revolution. By the time I was born in the Bronx, the family history beyond the Port of New York was fuzzy indeed — though ironically it was a famous Jewish art dealer who provided me with much additional information when I was in my late 20s. While I was studying art history, Leonard Hutton was revered for his collection of German Expressionist and Russian Revolutionary paintings. I spent a lot of time in his gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan during my student days, not yet aware of his personal history or our family ties. Hutton was born Leonard Hutschnecker in Germany. Like Paul Rosenberg, he too fled Hitler, and arrived in New York Harbor in the 1940s with a minimum of money, no friends and nowhere to stay. Thinking fast, he grabbed a phone book, and found only one Hutschnecker listed in the whole city. He called that number, explained his problem, and asked if perhaps the New York Hutschneckers might be willing to help him get started since the odds were that they were his relatives. The family in question agreed, and helped him get settled in America. He, in turn, swore he would construct a geneology, a family tree to honor everyone from the bloodline that had saved his life.

Which is, oddly, where I come in to this story. I was reading an article in the New York Times one day during the late 1970s; it was about Arnold Hutschnecker, a famous psychiatrist who treated, among others, Richard Nixon. My maiden name was Shelley Hutch, but my father was born Harold Hutschnecker. He changed his name to Hutch before his marriage, around the same time (and for the same reason) that Anne Sinclair’s father changed his name from Schwartz to Sinclair. Seeing the article about Richard Hutschnecker, I had exactly the same impulse as Leonard had years before. I called the psychiatrist’s office, and announced that I certainly must be his relative. To my shock, the nurse called the famous doctor to the phone and he arrived breathless, saying he had in fact been waiting to hear from me. He and his brother knew my grandfather, and knew about my father. They had been hoping that they would be able to learn more about — and meet — the latest generation of the Hutch family. But, Richard said, he wasn’t the one who kept the records of the family — I really needed to call his brother, the art dealer Leonard Hutton! He told me that Leonard would be thrilled to hear from me. My visit would allow him to fill in the gaps left in the family archive.

So in the late 1970s my family expanded to include the amazing (and now deceased) Leonard Hutton Hutschnecker (along with his wife Ingrid), who around that time had decided to re-adopt the family name shed during and after World War II. Indeed, it was true, Leonard had kept his promise: he had constructed a huge family tree, tracing Hutschneckers all over the world, as far as Russia, Switzerland and even South Africa. He was thrilled but not surprised to have found an art critic in the family. At the time I was writing columns for newspapers like the Village Voice and magazines like Artforum under the married name I still use. Considering that everyone else in my immediate family was an accountant, I seemed like a black sheep. But in the family as a whole, the global family, creative people (especially theatre people and interior designers) have predominated. What a relief!

I am recounting this story not only because it is a good one but also to make clear — yet again, and in a personal way — the tremendous impact the Nazis and the Second World War had on the circulation and the future of art, artists and intellectuals. This is precisely the general theme of Sinclair’s enlightening book, the tight lines between the personal, the cultural and the political, and the ways in which these various threads continue to surface (for better or worse) in contemporary life. She is strongest on her family history, and in describing (and sometimes questioning) her grandfather’s efforts on behalf of art, artists and social justice; she is weakest when discussing New York and its cultural history, which Rosenberg entered in mid-stream, hardly a pioneer. Picasso was shown in the city by Alfred Stieglitz before the Armory Show of 1913 and World War I; he didn’t need to wait for Paul Rosenberg to give him his first exhibition in the Big Apple around the middle of the 20th century, even though Sinclair’s grandfather certainly helped to solidify the European modernists’ acceptance and placement in major institutions and collections. This is one of the curious anomalies of the new book. As she admits, Anne Sinclair initially saw New York through the eyes of a child. In 21, rue La Boétie, she has attempted to retain her youthful enchantment with the city while telling a very grown-up story — a balancing act that doesn’t always ring true, especially since she herself mentions the ordeal of 2011, when her husband DSK had no choice but to remain in NYC while officials decided whether to pursue (eventually abandoned) criminal charges against him for the sexual assault of a hotel maid.

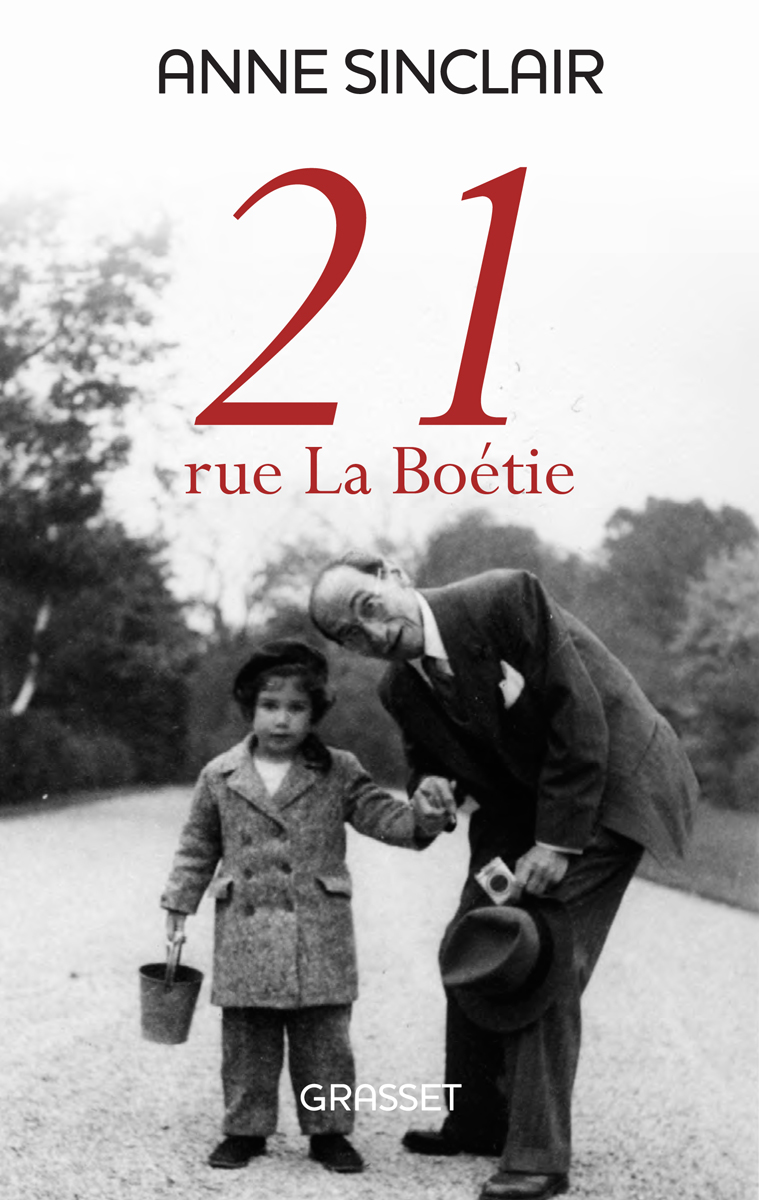

It must be said that much of my knowledge of Anne Sinclair, ironically, dates from this period, when television newscasts showed nightly images of the couple bombarded by reporters on the street when they dared to venture outside of their Tribeca townhouse. That image of her — as stoic and supportive wife — needed some fleshing out, with information about her professional accomplishments and her distinguished lineage, which is why I bought this book in the first place. But I must confess that my initial motivation for writing a Blog post was more concrete and more immediate than these intellectual concerns. I became obsessed by the black and white photograph of the young Sinclair and her grandfather printed on the cover of this memoir. In the picture, Anne is perhaps four years old. Facing the camera in what seems to be a park, she is holding the kind of bucket used in a sandbox and grasping her grandpa’s hand. And, most important for me: she is the spitting image of me in a number of family photographs retrieved from my parents’ haphazard archives and scrapbooks. A cute, chubby cheeked and dark haired girl, she is wearing the same coat and the same beret I wore as a child.

For some reason, this fashion coincidence freaked me out. It was as if I was suddenly faced with a mirror image. The repetitiveness of family snapshots, their conventional structure and style, hit home even across the Atlantic. The shock of recognition, in fact, was almost Barthesian: the photo confronted me head on with what Roland Barthes called the madness of history. There’s a section in Camera Lucida where the author talks about “history” being the time when his mother lived before he was born, without him. Whereas this “historical” time was a void for Barthes, I had the opposite reaction to Sinclair’s image. A plenitude of historical details flooded into my head when I realized the implications of this family snapshot. I don’t know this person, she is French and living a very different life from mine. So how is it that she is wearing my coat, and why do we look so much alike?

It took me a while to realize that while we inhabit different worlds today, by accidents of history Anne Sinclair and I were two well-dressed Jewish girls about the same age during the same historical moment (the early 1950s) in New York City. We surely played in the same parks, perhaps even in the same sandboxes, and obviously both of our families bought into the vogue for safeguarding family memories in snapshots made simple by new technologies. And yes, I probably am not imagining it, our mothers could easily have purchased nearly identical coats for their young (and pampered) daughters. My coat, as I recall, was slightly fuller at the bottom, but the wool tweed and the collar were absolutely the same, and I can never forget that great hat (which I must admit looks as cute on her as it did on me). In the years after this picture was taken, Sinclair would, of course, go back to Paris and make a name and a life for herself in France, while I would do the same in the Big Apple, and there this story might have ended. But the photograph grabbed my attention, and made clear connecting links buried in time, space and family archives — as well as in the annals of commerce. For my mother only bought coats at Russeks, the now defunct Fifth Avenue store owned by the Nemerovs, the family of Diane Arbus. If we did, in fact, wear similar coats, perhaps the Sinclairs shopped there too. It is, indeed, a very small world.

© Shelley Rice 2012