Paul Graham: "23rd Street, 2nd June 2011, 4.25.14 pm" Two pigment prints, each mounted to Dibond. Diptych from "The Present" © Paul Graham, 2012 Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and The Pace Gallery, New York

Paul Graham, The Present (Pace Gallery and Pace/MacGill, February 24-April 21, 2012), by Shelley Rice

From my perspective, April 2012 was a momentous photo moment, in a quietly profound sort of way. On 22nd Street in Chelsea last month, there were two exhibitions – one at Pace Gallery by Paul Graham and one at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. by Mitch Epstein – that announced the opening of what Graham (recent winner of the 2012 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography) has called “a space for photography to work in the world.” He obviously doesn’t mean this literally, since millions of amateurs walk the streets of the 21st century snapping pictures and photographs have all but dominated the art world in recent years. What he means is more subtle, and as I recall I first heard him talk about it at a MOMA Forum a few years ago. These MOMA Forums, first convened by Roxana Marcoci and her colleagues in the Photography Department in February 2010, are a valuable addition to the New York scene. Bringing together a lot of different kinds of people from the community about three times a year, the soirées encourage discussion and debate between artists old and young, curators and critics from the United States and abroad, educators and academics. The viewpoints that swirl around during the two hour Forum (and the informal receptions before and after) pinpoint the differences, similarities, goals and pet peeves of an increasingly diverse and global crowd. One division, however, has been especially clear, mainly because it was so deftly articulated during the early séances by Graham himself: the divergent approaches to the medium that define the practices of those whose formation was strictly photographic as opposed to those who came into the field through conceptual art, performance or postmodernist strategies.

There were, naturally, arguments about this division: younger curators especially seemed to think that such a divide was no longer relevant, while those of us who’ve been in the field for a while (and that does include me) are loathe to simply turn our backs on the classic history of photography in our rush to embrace more contemporary ways of working. But Graham, as I recall, was particularly eloquent that evening in his defense of tradition: the extraordinary power of what Edward Weston called “photographic seeing,” the expressive means invented and honed to perfection by image-makers like Robert Frank, Harry Callahan, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. An old fashioned artist, Paul Graham studies the work of his forebears with obvious reverence, understanding the skill and vision that underlie what might seem like a simple image. His latest exhibition, The Present, was his homage to those who have climbed what he calls the “Himalayan range” of New York street photography.

Born in the UK, Graham now lives in the Big Apple, making him one of the latest in a procession of New York photographers — Frank, Lisette Model, Andre Kertesz, Sylvia Plachy among them – who use the camera to describe their adopted rather than their native environment. In a thought provoking interview with Arthur Ou published in Artforum.com in March, the artist described the challenge he faced paying tribute to the legacy of the street photographers from the 1960s and 1970s while moving their genre into a more contemporary place. Graham’s “present” is perceived in dialogue with the past captured and preserved by predecessors like Winogrand and Friedlander. With every picture he takes, of course, his “now” slips into that past, to await the gaze of the future. This inevitable temporal flow defines what Graham describes as “the unique qualities of the medium, and its struggle to deal with time and life. I think those are our materials. Not film, not paper.”

For a critic who sat on stoops with street photographers during the 1970s, such talk sounds familiar. I recognize the grappling with time and form and technique, with the metaphoric possibilities of momentary arrest in defining the ebb and flow of the city. Such engagement is not the same as a postmodernist strategy; immersed in time and space, an image-maker like Graham speaks with a different mode of address than a Philip-Lorca diCorcia, a Gregory Crewdson or a Jeff Wall, artists who set up situations or create directorial tableaux and who dominated the scene during the 1990s. Responsive, reactive, a classic street photographer attempts, as Graham describes it, to “dance with the Brownian motion of life,” and in the process to visualize “the world as it is.”

Paul Graham: "34th Street_4th June 2010, 3.12.58 pm" Two pigment prints, each mounted to Dibond. Diptych from "The Present" © Paul Graham, 2012 Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and The Pace Gallery, New York

“I go out and try to find answers to the question ‘How is the world?’” he explained in an article in The Financial Times. The world described in his exhibition at Pace Gallery consisted of 16 diptych and 2 triptych photographic works taken on New York City streets within the past few years. Twin images separated only by the briefest fraction of time, the “sibling photographs,” as the press release calls them, allowed us to see “life and its doppelganger arrive and depart.” The power and meaning of these large-scale color works (the diptychs measure 12 feet wide and the triptychs more than 18) was reinforced by the installation. Hung a few inches off the floor, the pictures gave the startling impression of a panorama unfolding right in front of and beside the viewer, at his/her height and in his/her continuous physical space.

Drawn into the action in this way, the spectator morphs into a pictorial subject – in the same way, of course, that all flaneurs are simultaneously voyeurs and participants in the spectacle of the city. Graham emphasizes that this is not ordinary black and white, 35 mm street photography. Not only are the pictures in color, but they are deliberately made with shallow focus, which he sees as more true to the way we actually see. The viewer focuses on one pedestrian or sign or gesture, and then passes on to the next detail – or the adjacent picture, where suddenly time and change rearrange and reveal alternate readings or new events. People move out of the picture and disappear, while others remain immobile; sometimes they fall, or fall behind. Policemen appear to investigate legs mysteriously protruding from behind a pole; trucks change position and in the process reveal formerly invisible city streets. Graham said that instead of “ossifying” the world into a singular moment, he sought to “invite time into the work, making it a quality you feel and experience.” He is not the first photographer to use “sibling” images a frame or two apart. Around 1980, Eve Sonneman produced smaller color diptychs, with a range of subjects including still lives, that were a shown at Castelli Graphics. But Sonneman’s work grew out of conceptual art; her slight shifts in time focused on formal affinities and the enigma of photographic stop-time. Graham’s duos, on the other hand, are about perception, about interiority, about the experience of being enveloped by the multiplicity of events in constant motion on city streets. They reanimate the freeze frames of Winogrand, allowing pedestrian traffic to flow like Stieglitz’s clouds, never congealing into narrative form. Graham put it this way: In these pictures, he wrote, “you see how events unfold, not only externally but also internally, from the consciousness-flow as we go about our lives.”

Paul Graham: "Penn Station, 4th April 2010, 2.30.31 pm" two pigment prints, each mounted to Dibond each image and paper, 56 x 74 inches © Paul Graham, 2012 Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery and The Pace Gallery, New York

It’s probably obvious that I am bowled over not only by Graham’s images but also by his words, by the intelligence with which he enacts and then describes a creative process that quite literally updates the classic definitions of street photography – in the process allowing this hallowed form of expression to take its place with dignity among the large scale prints that have dominated museum exhibitions in the past two decades. The Present was a love song to photography, but it was also an announcement that the practitioners of this medium can now dialogue, in full awareness, with artists who use the camera in other ways. As Graham says, he has taken his knowledge of recent photographic practice and “brought it into play with life-as-it-is, and this closes the circle.” Bravo to him, and to his colleague Mitch Epstein, whose exhibition across the street (to be discussed by my colleague Rob Slifkin, an Assistant Professor at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts) added to my conviction that in fact classic photography is being born anew, right now in front of our eyes, once again.

(This work will travel to Carlier/Gebauer in Berlin in April and Le Bal in Paris in October of 2012.)

Mitch Epstein, Great Trees (Sikkema Jenkins and Co., March 16-April 14), by Rob Slifkin

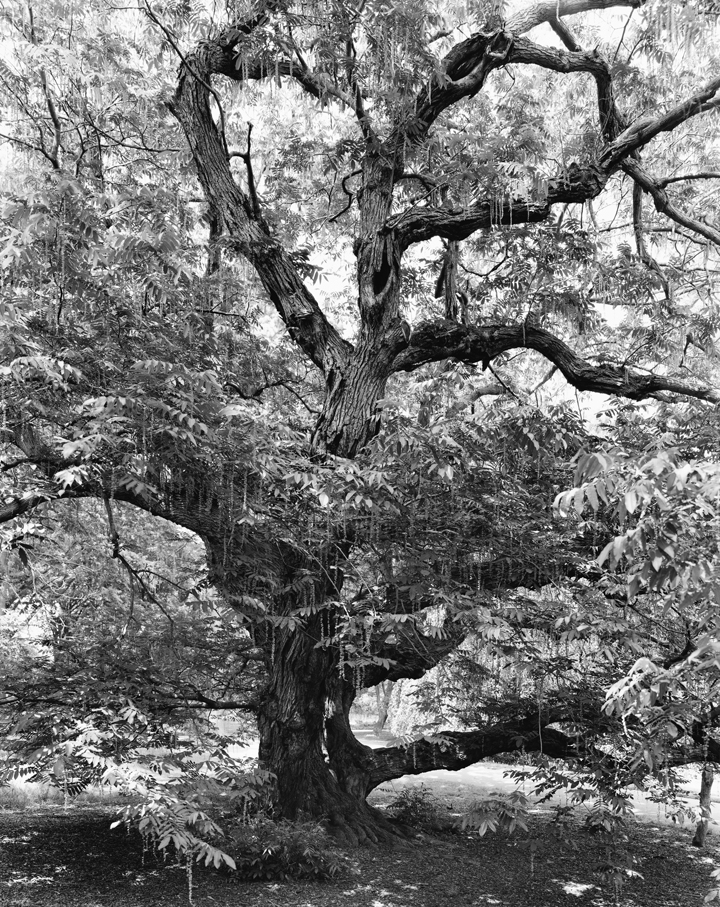

One of the most captivating capacities of a photograph is its facility in preserving a discrete moment in time. Paradoxically, this instantaneous historization becomes increasingly fascinating the further we are separated from the moment the picture was taken, the passage of time accentuating the differences between those frozen images and the continued existence of what they depict in the ever-changing world, turning every photograph, as Roland Barthes famously remarked, into a premonition of death. While I have likely walked past the towering English Elm that has grown in the northwest corner of Washington Square for over three centuries hundreds of times, and even stopped on occasion to admire its astonishingly wide trunk and wide-ranging canopy, I initially didn’t recognize its portrayal when I saw it from across the gallery in Mitch Epstein’s recent show of large black and white photographs of monumental trees in New York at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. in New York. No doubt much of this has to do with Epstein’s brilliant lens work, which is able to broaden its view to capture an isolated portrait of the tree that no human eye immersed within the typically busting pubic park could even discern. Like almost all of the trees captured by Epstein’s camera, the elm dominates the large print, its extensive and leafless branches determining where the photographer cropped his shot. Confined within one of the world’s most imposing and congested environments, the trees of New York are unfortunately all too often forgotten or ignored. Epstein’s meticulous portraits, in which the shallow patterns of recessed bark and the subtle tonal variations of different leaves are all rendered with a precise but never cold intensity, present these colossal beings as both fragile and awe-inspiring, and worth being concerned about.

Mitch Epstein: "Caucasian Wingnut, Brooklyn Botanic Garden 2011" © Mitch Epstein / Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Inspired by a list of 100 great trees assembled by the New York Parks Department, Epstein traveled throughout the five boroughs, the botanical landmarks taking him to neighborhoods and urban territories that are frequently forgotten and rarely represented. Potent symbols of both the endurance of nature and the frequent human folly that attempts to compete with it, Epstein trees extend the photographer’s longstanding interest in mankind’s disruption of our environment. This theme was perhaps most clearly addressed in the justly celebrated series of photographs Epstein took between 2003 and 2007 collected in his book American Power, which documented the way in which the energy industry has affected the landscape of rural and suburban areas throughout the United States with a body of photographs whose resplendent, colorful detail and compositional wit encourage sustained viewing and contemplation. As in the American Power photographs, Epstein in his new work typically addresses this theme of human engagement with nature without recourse to the inclusion of actual people. Instead it is the way the human environment clumsily perches itself upon and amidst the natural world that defines Epstein’s approach to landscape. In the new series, the human artifactual impositions move to the margins, letting nature take center stage. (That said, these photographs, in their human-scale proportions and discrete subjects, are closer to portraits than landscapes, an aspect enhanced by the often anthropomorphic rendering of the trees, presenting some of them empathetically leaning to one side or focusing on their contorted, flesh-like bark and knobby protuberances.) Often Epstein’s subjects, many of which ended up in the city as diplomatic gifts, are portrayed as stoic and noble prisoners, as in a White Oak in the Bronx. A complex tangle of its braches emerge out of a scrubby copse of trees whose own less brawny intertwinings find a geometrical resolution in the windows of a apartment building residing in the distance. Epstein’s uncharacteristic use of black and white further urbanizes his subjects, giving them a tone corresponding to the cement and glass that surrounds them, while at that same time diminishing the clangorous palette of the city so that the trees might be equals if not superior to their environs.

Mitch Epstein: "English Elm, Washington Square Park, New York 2012" © Mitch Epstein / Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

While the tree portraits might appear as a drastic change from Epstein’s previous output, trading in an ostensibly more overt engagement with social issues for an almost romantic appreciation of natural beauty, the social-environmental subject matter that motivated the American Power series is also present in these new works. As battered urban survivors, Epstein’s trees become monuments to the ways in which human history and natural history converge. Most of the trees Epstein chose to depict are over one hundred years old and their survival within the rough and tumble environs of the five boroughs has left its traces on them in myriad ways: gnarled and stunted branches, constricted roots buckling under the stress of pavement, and most disturbing, the scars left by the incisions of countless lovers and vandals. Epstein has noted in a recent interview that traveling abroad has sensitized him to the relative brief history of the United States. By focusing on trees planted in what has been one of the most artificial environments in the United States, many of his subjects can be seen as witnesses to the entire history of European occupation of the New World. One thinks of all the passersby who have crossed under the tree’s shadow in Washington Square (which is, in fact, known as “The Hanging Tree”); or perhaps what the now suburban neighborhood in Staten Island looked like when the giant Eastern Cottonwood tree, which stands over the white clapboard condominiums like Diane Arbus’s Jewish giant over his meek parents, was planted (a question whose historical intrigue is emphasized in the hazy light in which Epstein presents the towering behemoth). Epstein’s new body of work, full of technical mastery and visual intelligence, exemplifies the sort of art being produced today by photographers like and Rineke Dijkstra, Thomas Struth, and Jeff Wall that, while grounded in a fundamental respect and understanding of the medium, stands alongside any other form of artistic production. If Epstein’s work represents this broader apotheosis of photography within the art world these new photographs suggest an eerie premonition of a time when the medium’s hard-won acceptance into the realms of high art might be complicated by the medium’s still-vital documentary capacity. Despite their undeniable beauty and complexity (or perhaps because these qualities seem tinged with a degree of melancholy), I couldn’t help but wonder if there may come a time when these photographs might appear in natural history museums or botanical archives as documents of now extinct species? Photography, it seems, can never wholly escape its vernacular and utilitarian purposes and the best photographs, like those of Epstein, make this burden into a virtue.