Untitled, 1987 - 1988 © Rotimi Fani-Kayode / Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Autograph ABP, London

I’m feeling like men are in need of equal time on this Blog.

They have, as usual, had more than equal time on the walls of New York galleries and museums this month. But I am less interested in numbers than in a confluence I’ve noticed recently: two of the exhibitions by accomplished photographers in Chelsea galleries this spring, one an American and one an African, one living and one dead, use male subjects to embody an edginess, a nihilism even, that tilts the idea of patriarchy wildly off center. Exploring the works of Alec Soth and Rotimi Fani-Kayode together is not a self-evident choice, but I’m thinking that the juxtaposition may yield some insights into the farther reaches of the male psyche during these early years of the 21st century.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, in fact, never made it to this new century: he died of AIDS in England in 1989 at the age of 34. Born in Nigeria to a prominent Yoruba family who fled to the U.K. as political refugees in 1966, he studied in the United States (a B.A. from Georgetown University in D.C. and an M.F.A from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn) and then returned to Britain to live and work. Active in both the Association of Black Photographers and the lively queer culture in England, he saw his photography as both a public and a political act – a suprising perspective, considering that his work consists mainly of male nudes in both black and white and color. “We aim to produce spiritual antibodies to HIV,” he wrote with his partner Alex Hirst. Transforming symbolic gestures into public acts bearing witness for a generation decimated by disease, he responded to imminent death by asserting the power of beauty.

Nothing to Lose IV, 1989 © Rotimi Fani-Kayode / Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Autograph ABP, London

While there are black and white works in this exhibition that can hold their own with Robert Mapplethorpe’s, the large color prints in the Nothing to Lose and Every Moment Counts series express his vision at its greatest intensity. Undressed (or occasionally dressed in African or Biblical robes) and adorned with feathers, fruits, leaves, masks or paints, black men adopt highly ritualized postures and gestures – though, as Kobena Mercer has pointed out, these actions only deepen the enigma of what the ritual might actually be. Christian, Yoruba (the artist’s family members, in their native country, were the keepers of the shrine for Yoruba deities) and other religious icons meet and meld in these works. Mercer calls Fani-Kayode Afro-Modern in his emphasis on the generative possibilities of cross-cultural exchanges and encounters. But the stylized language of the body is what makes these pictures so extraordinary. This is a Dance of Death, a dance to the death, a defiance of shame, fear or anger. Independent of nationality, race, religion or ideology, born of the artist’s displacement (he called himself an outsider in matters of sexuality as well as geographical and cultural dislocation), this ecstatic theatricality shatters the chains of culture to illuminate more profound and ambiguous aspects of the human condition.

Fani-Kayode, in other words, uses the expressive powers of the black male body to assert the transcendent force of the finite, the transient, the mortal. This push beyond the confines of particular civilizations is a leap of faith, an affirmation of the primacy of life beyond bounds. His sitters bite into apples, sprout feathers, cover themselves with plants and berries, uniting their flesh with nature in both its concrete and its metaphorical manifestations. Men also bedeck themselves with flora in the latest works by Alec Soth, but the meaning of the gesture in his photographs is completely different. While Fani-Kayode’s subjects are adorned with leaves, affirmation turns to negation when Soth’s are practically (and willfully) obliterated by them.

The Broken Manual exhibition at Sean Kelley Gallery this spring was a curious and hybrid affair, comprised of a number of photographs (black and white and color, most taken between 2006 and 2010), a documentary film and a site- specific installation showcasing the book by the same title. Ostensibly written by Soth’s alter ego, Lester B. Morrison, the book is a how-to survival manual designed to aid others (men, of course) anxious to withdraw from society and build a life in some remote part of the American terrain. The adjective American here is very important. Even though Soth emphasizes that he first became fascinated by hermits when he began studying the life of Trappist monk Thomas Merton, he was moved to begin this project by the story of the Olympic Park bomber Eric Rudolph, who spent years evading police by hiding in the Appalachian Mountains. Alex Soth is, from my point of view, one of the great American storytellers, with an extraordinary sensitivity to the strength and the strangeness of this young and mysterious land and its motley collection of citizens. The Broken Manual exhibition is one of the chapters in his ongoing story, the chapter about a breed of men who never quite emerged from the Wild West into what we so blithely call 21st century life.

Whereas Fani-Kayode’s men will themselves beyond specific civilizations and belief systems in order to reaffirm both the ecstatic nature of life and the archetypal rituals that sustain it, Soth’s reject human society and collectivity outright. As the press release says: “These photographs reflect (the artist’s) increasing interest in the mounting anger and frustration that some specifically male Americans feel with societal constraints and their subsequent desire to remove themselves from civilization.” “Primitive” in these pictures does not refer to traditional tribal ancestors, it means shedding the trappings of culture altogether and living in the woods with (and sometimes like) the animals. In this moral universe, one covers oneself with leaves or branches in order to hunt or evade the authorities; one declares one’s allegiance to nature as a way of turning one’s back on the alternative. Soth’s photographs sometimes show the men, and sometimes their living environments – in caves, on or inside mountains, in trucks or dilapidated sheds. It is a testament to the photographer’s extraordinary sensitivity that he was granted access to these guarded people, who maintain both a psychic and a physical distance from his camera but who are, nevertheless, in clear contact with both with him and us. Constantly lurking beneath the surface of these images are the alienation and rage that sustain the hermits’ withdrawal, their “escape.” This is, in other words, not Thoreau’s America; and the Broken Manual, teaching lonely men how to survive on the lam, makes manifest a dark side of American life that keeps threatening to erupt into the national consciousness – and political process.

Edgy men also made their appearance in The Utopia of Difference, the first American exhibition by Vibha Galhotra, a young Indian woman living in Delhi. But the edginess in this artist’s work is urban rather than natural. Whereas Soth’s hermits disappear into the camouflage of trees, Galhotra’s sculptural figures wear army-style Neo-Camouflage imprinted with the image of the city dominating the wall behind them. Impossible to visually extricate from the overcrowded geometries of their environment, the mannequins morph into cyborgs whose organic flesh lives to reflect the architectural chaos of their surroundings. Escape from society, in this case, seems impossible. Unlike the empty wilderness that still covers much of the United States, whose existence is essential for the tales Soth tells, the urban jungles of India depicted in Galhotra’s work seem to go on forever. No Exit, as Sartre would say.

Vibha Galhotra Neo Camouflage, 2008 digital print on fabric and vinyl, mannequins, shoes, and belts dimensions variable (site specific). Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Gallery Espace, New Delhi

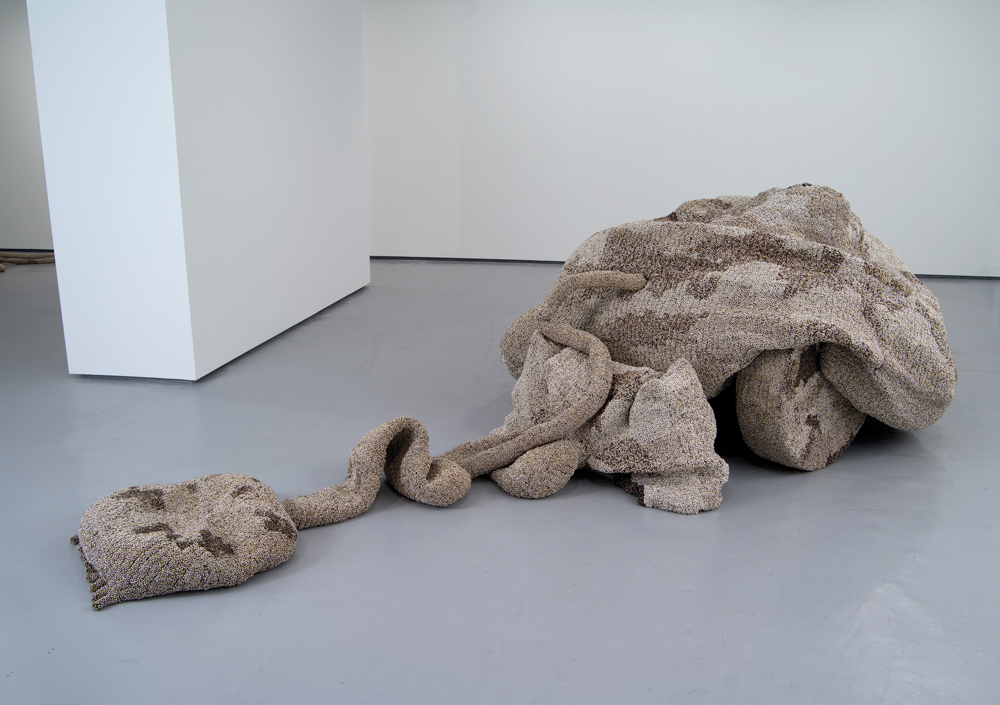

This photographic project set the stage for the exhibition, but much of the work consisted of sculptures and textural wall pieces sewn together with metals and other materials. A hammock swings the image of the world in crystals; a beehive amassed from metallic beads juts out beneath the dark and varnished wood of an old European table. Galhotra is an extremely versatile and inventive artist, practiced at using the media, symbols and metaphors of our newly globalized world in ways that disrupt their accustomed usages and meanings. Organic and inorganic, urban and natural, male and female: these are the parameters continually being tested in her visual expressions. The shimmering brass or copper surface that is a hallmark of her work, for instance, when viewed up close, is constructed of many ghungroos – the small ankle bells worn by Indian women as a musical accompaniment for traditional dance. Once these metal beads are sewn together, en masse, they are capable of morphing not only into hives and ropes or words and cityscapes drawn on fabric but also into large and monstrous animal forms that are like a cross between a Lynda Benglis and a Claes Oldenburg soft sculpture. Part dinosaur with claws, part wheeled vehicle with a crane for a neck, these “monsters” are the artist’s variations on what Gayatri Sinha calls “a collapsed and somehow humanized earth mover.”

Vibha Galhotra Dead Monster, 2011 nickel coated ghungroos, fabric, polyurethane coat, thread, and steel dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Gallery Espace, New Delhi

I stared at the Dead Monster for a long time last week, noting the folds of its “skin” flopping over the architectonic body beneath. I then walked home by way of the High Line Park, and stopped to stare down at a construction pit on Gansevoort Street in the West Village. A big, bright yellow CAT earth mover was perched precariously on a huge mound of brown dirt; its “scoop” reached into the earth at odd angles, digging and clutching and swaying with a rhythm that was as mesmerizing as it was disturbing. I knew as I watched that I was, indeed, experiencing Galhotra’s Beast – the one familiar to all of us who have chosen not to escape from the global cities of the 21st century.

SR

© Shelley Rice, 2012