The Jewish Museum, November 4, 2011 through March 25, 2012

Curated by Mason Klein of the Jewish Museum and Catherine Evans of the Columbus Museum of Art, this important exhibition draws on two museum collections with rich holdings on the history of New York’s Photo League. Begun during the Depression, the brainchild of photographer and teacher Sid Grossman, this organization – which encompassed darkrooms and meeting rooms, lecture series and photography classes, exhibition spaces and a newsletter called Photo Notes — was seminal to the formation of New York’s late 20th century photography community. But despite its considerable influence, little has been known about this chapter in the city’s cultural history, in large part because the League and its founder were blacklisted by the government during the Communist Scare of the 1950s. This is the first museum exhibition in three decades to comprehensively explore its contributions in order to correct what Klein calls “a historical myopia”, and it is a terrific show well worthy of its complex subject.

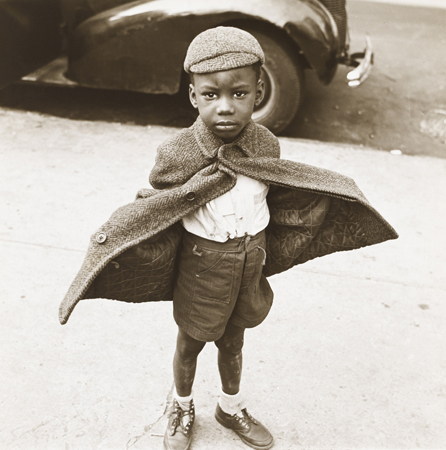

Jerome Liebling, "Butterfly Boy", New York, 1949, gelatin silver print. The Jewish Museum, New York, Purchase: Mimi and Barry J. Alperin Fund. © Estate of Jerome Liebling.

Founded to provide instruction and meeting places for photographers and artists who were often the children of immigrants, The League has been known primarily for its Socialist-oriented, left wing politics and its rejection of the artsy and elitist Salon style of the Pictorialists. Faced with the diversity and the dilemmas of urban life during the Depression, idealistic young people like Walter Rosenblum, Aaron Siskind, Max Yavno, Helen Levitt and Morris Engel chose photography and aimed to follow in the footsteps of supporters like Lewis Hine and Paul Strand. Famous artists and critics – Lisette Model, Berenice Abbott, WeeGee, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and Elizabeth McCausland for example – counted themselves among its contributors, and artists as far-flung as Edouard Boubat, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Alvarez Bravo were invited speakers. In other words, in spite of its urban emphasis and its general leftist tendencies, the League was a lively, open-ended and global center of photography open (and economically accessible) to everyone.

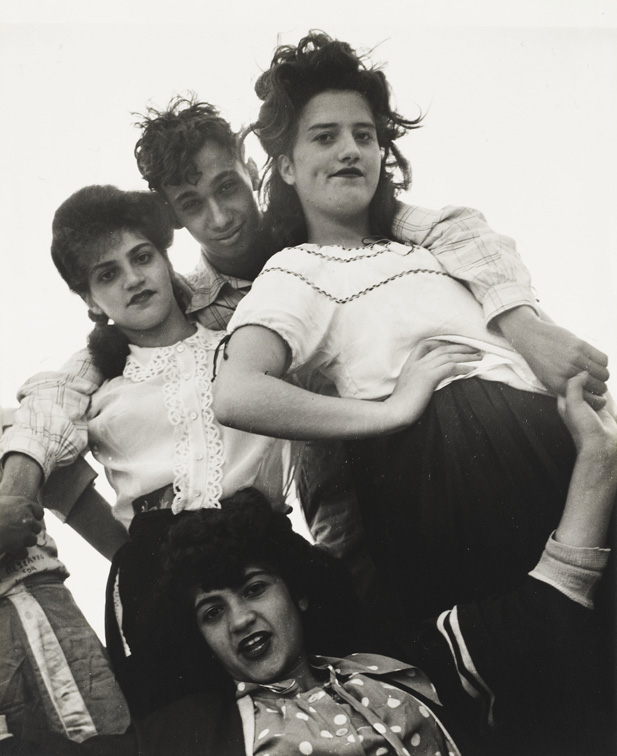

Sid Grossman, "Coney Island", c. 1947, gelatin silver print. The Jewish Museum, New York, Purchase: The Paul Strand Trust for the benefit of Virginia Stevens Gift. © Howard Greenberg Gallery.

This is significant, and it is also a central tenet of both the exhibition and the excellent book that accompanies it. Most discussions of the League in the past two decades have emphasized either its political ideologies or its “camera club” aspects, and neither of these points of view tell the full story. While many of its members were deeply engaged in documenting the social and political complexities of their surroundings, Grossman’s emphasis was always on the evolution of the photographer in relation to his or her subject – the formation, in other words, of a personal photographic vision that allowed the artist to perceive him/herself within the environment described. The demands of this vision changed over time, as the Depression gave way to World War II and then the unexpected prosperity and political hysteria of the postwar years. The Radical Camera’s greatest triumph is in its ability to trace not only the historical shifts but also the evolving definitions of photography that characterized members of this talented group. The relationship between the objective world and subjective vision, between documentation and art, was constantly being negotiated within the organization. Klein emphasizes that personal interpretation came to the fore in the later years of the League, in a poetic documentary style that was further developed in the works of the more solipsistic New York School artists – Robert Frank and Louis Faurer among them – who came to represent American photography during the 1950s. The complexity of this shifting ideology and aesthetic, the range of expressions set forth within its theoretical and pedagogical arena, are palpable on the walls of the Jewish Museum, embodied in wonderful pictures that continually interrogate the relationship between the world and the image-maker’s eye. It has taken a long time, but this remarkable group of men and women has finally vanquished the blind spot created by their prejudicial past, and taken their rightful place within the histories of both photography and the city of New York.