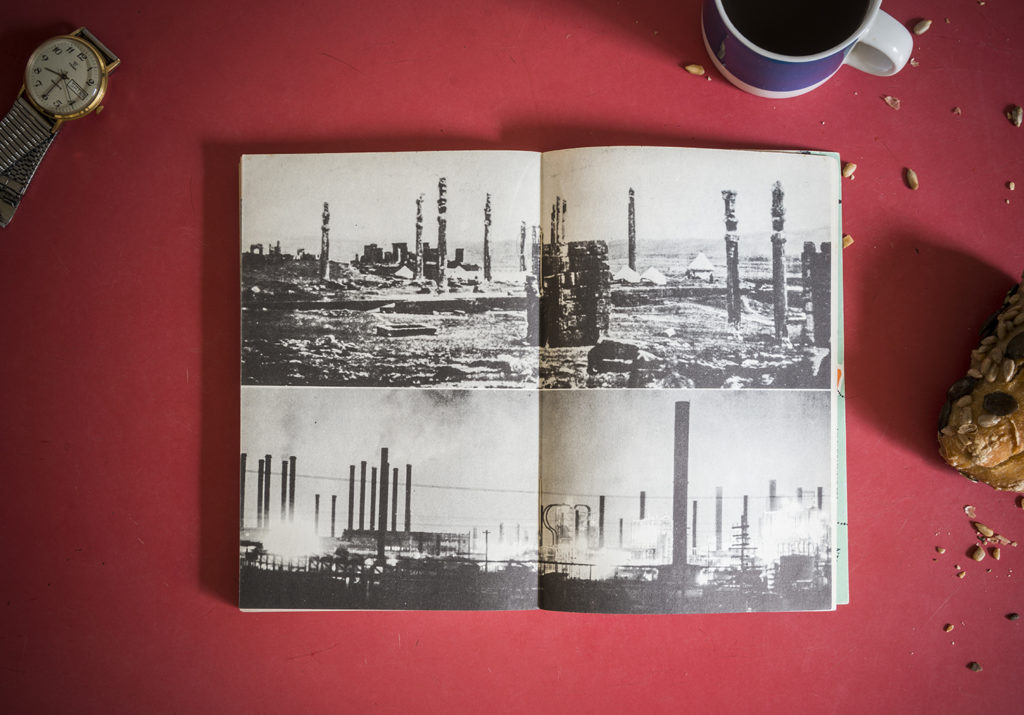

Vincent-Mansour Monteil, Iran, Chris Marker (ed.), Paris, Éditions du Seuil, series Petite Planète (“Small World”) n° 13, 1957, p. 184-185. Photos Atlas-photo. All rights reserved.

The small book Iran, appeared in 1957 under the imprint of Editions du Seuil. It was number 13 in the series Petite Planète (“Small World”), a series of travel guides edited by Chris Marker, who, though largely unknown as a filmmaker at the time, displayed a disconcerting spirit of inventiveness in the book. He handled the Iranian iconography like a film editor, tackling the layout of the book the way a film editor would approach the rushes of a film on the editing table. Marker offered his readers a plethora of dazzling analogies and elective affinities between ancient Iran and modern Iran, historical documents and street photography (including a popular iconography of drawings, advertisements, caricatures and so on), ethnographic discourse and a critique of exoticism. He had no scruples about witty comments or puns to describe the pictures, or applying his unbridled taste for anachronism, incongruity, and the astonishing.

Iran was presented from every angle, those most useful to the tourist and the student of history, as well as other, completely gratuitous, views, which at times bordered on aesthetic self-indulgence. One example, more or less emblematic of the entire guide, will plunge us effectively into this kaleidoscopic vision of Iran. At the end of the book, we are presented with a full-page juxtaposition of two panoramic photographs, placed one above the other: in the top half, a landscape of typically antique ruins on the archaeological site of Persepolis, dotted with columns and solitary stones; below it, a contemporary (to Chris Marker) landscape of an oil refinery with its smoking chimneys under an opaque, grey sky – probably Abadan which was the largest oil field at the time. A fundamental constellation seems to be in order. Given the role played by oil in the Cold War era, Marker combined capitalism and ancient conquests in the same spatio-temporal unit – modern geopolitics and the sacking of Persepolis by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE. As if to suggest that the power struggles between “Persians” and foreign powers still continued in other forms. For the Iranian people, the 1950s represented the apogee and decline of the workers’ struggles against twin forces – at home and abroad – exerted almost as a matter of course on the country’s human and energy resources. Those forces began with the signing of the D’Arcy Concession in 1901, which gave British businessman William Knox D’Arcy exclusive rights to prospect for oil in Iran, and continued with the monopoly of companies like the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, later renamed the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). Then there was the 1953 US coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, and the problems that arose from the nationalization of Iranian oil. Beyond the frontiers of Iran, there was the 1956 Suez Crisis, and the Eisenhower doctrine, which involved the United States in using its influence over the Middle East as a means of containing the communist threat. In fact the mixed history of socialism, Marxism and nationalism, with the Tudeh Party in Iran, the Ba’ath Party in Iraq and Syria, and Nasserism in Egypt, covered multifarious realities and indissoluble links in Khrushchev’s Middle East policy. In these different contexts, war often entailed a state of mutual and permanent control, and multilateral threats lurking in the recesses of internationalist utopias, and deeply felt urges for cultural renaissance resonating beyond the borders of Western Europe and the United States. The history of this period is of course non-linear. More than anything, it is multifocal. It is not strictly speaking “global”: the movements of that time, from the Teheran and Havana Biennials to the pan-Arab exhibitions in support of Palestine, were part of a rhizomatic history of the visual arts and cultural groupings. Interpreting them involves not so much a structured historical system as a principle of connectivity and superposition (the synergy between political events and artistic events). It may be that it was a period that can only be properly understood in terms of geopolitical breaks, but also by the intermediary of one particular factor, a product of both natural history and political history, a factor that was both geological and ideological, as omnipresent (omniscient even) as unconscious: namely Oil.

The US’s 1953 coup against nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh – despite the sporadic expulsion of foreign companies and more balanced wealth-sharing agreements –, was a fundamental break in a surge of popular sovereignty. In Chris Marker’s montage, the ancient ruins seem to lie in wait for modern ruins. And those ruins eventually came to pass with the destruction of the Abadan oil-refinery during the Iran-Iraq war. Anachronism projects a light over the 1950s like a Freudian psychological structure, the superego or the psychic apparatus that preserves emancipatory impulses from their own effusiveness, an apparatus of power or control in short. The superego of oil acts like a kind of after-image, a survival of the old classical landscape in the face of industrial conquest: like a swing of the historical pendulum whereby the columns of the Achaemenid temples take the place of the oil distillation columns and vice versa. Mineral fluxes versus vital fluxes. Stone and oil alike belong to the cosmogony of minerals. Notwithstanding that one is combustible and the other is not, both are still active agents of schizophrenia in which all progress towards progress and civilization – indeed any attempt to transcend matter through culture – inexorably accompanies a fantasy of destruction and a sympathy for war.

PP

#For Ervand Abrahamian, “The nationalisation of oil was the equivalent for Iran of what independence was for many of the former colonies in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean.” (Ervand Abrahamian, The Coup: 1953, The CIA and the Roots of Modern U.S.-Iranian Relations (New Press, 2013), p. 79)

Translated from French by Jeremy Harrison