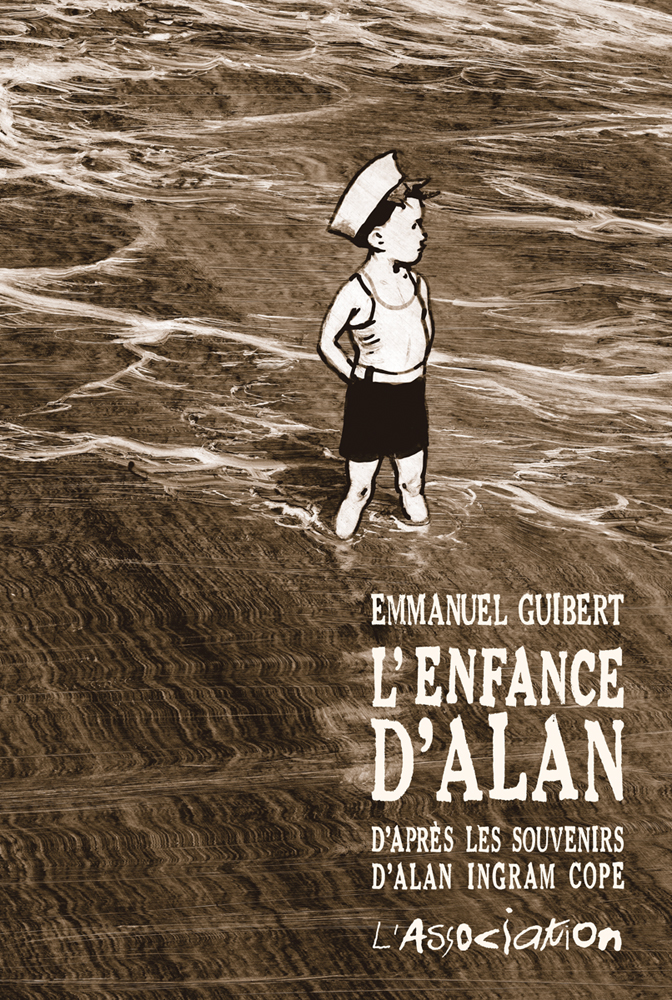

Well known for his drawings, cartoons, storytelling and animated characters like Ariol (the small gray donkey created in collaboration with Marc Boutavant in 2000), Emmanuel Guibert is the author of a number of books, among them The Photographer (with Didier Lefèvre) and Alan’s War. Emmanuel fascinates me because he explores the boundaries between photography and drawing, memoir and fiction, using elements from different sources in order to tell tales about love and war, childhood and friendship. His intense interest in the stories of others, and his uncanny capacity to highlight and empathize with universal human experiences – whether profound or mundane, traumatic or serene – are hallmarks of a body of work that might chronicle centuries and continents but that always communicates through the tiny details of everyday life. I met with Emmanuel on Sunday, July 16 in his studio in Paris, to discuss his new book La Jeunnesse d’Alan (Alan’s Childhood), which will be published in France by L’Association on September 14, 2012.

SR

Emmanuel: So, Shelley, what would you like me to talk about?

Shelley: First, can you give me an overview of this project, since this is the second book you have written about Alan Ingram Cope and we need to inform our readers about its history.

E: Alan and I met in 1994 on a tiny island off the coast of France called the Ile de Ré. I asked him for directions on the street and after that we became friends. We stayed friends for five years, from the moment we met until the moment he died. In the meantime, I taped hours and hours of conversation between the two of us to gather this patrimony, which would allow me to turn this man’s experience into biography.

S: But why him?

E: Complete chance, just because we had some sort of crush on each other. I felt he was a very interesting person and I wanted to spend time with him. It just started like this. He was retired. He invited me to his home, he introduced me to his wife, his dog, and then his life. He showed me some pictures, then some books, and very soon I found myself meeting with him in the little garden he had near his house on the Ile de Ré to talk and tape conversations. The conversations became stronger after a while as he opened his memory and his philosophy of life to me more and more. I was thirty at the time, and it is always interesting for an inexperienced man to speak with someone who can see his life in perspective — a view of life that can be both an overview and a close up, something only possible for an older person. It was fascinating for me. The main thing I can say is that he was one of the people in my life with whom I’ve spent the most memorable moments.

So I started very soon to turn his testimony into drawings, because I thought it would be interesting for him to see his memories coming back as drawings done by someone else, to see if that worked and if he would allow me to interpret his memories. They couldn’t fit exactly because I hadn’t lived what he had lived, but I listened carefully to him to catch all the words and the images linked to the words. I knew that we could go quite far together if he would accept my interpretations, and I was relieved because the first time I came with my drawings he was very enthusiastic. We both felt that this was a way for our friendship to go on. We worked together for five years, from the time he was 69 years old until his death at 74. I worked hard to make sure he could see the first book but unfortunately he died six months before it was released.

S: Can you talk about the first book and why you chose that aspect of his life – his experience as an American soldier in the Second World War — for the initial volume?

E: We had the opportunity to be pre-published in a magazine (Lapin), every three months, with no limit to the number of pages…

S: Wow, that’s like Balzac…

E: So I started to create episodes about this childhood, but after a while he said: “We have this regular appointment with readers. Maybe we should tell them something that can be like one story, like a feuilleton…”

S: Like Balzac!

E: He said the best thing to do might be to tell the story of “his war,” because it has a beginning and then it is a voyage: you are in a vehicle, you are sent abroad, you cross Europe and end up at the border of Czechoslovakia…. This is really a story to tell in a magazine. So I stopped working on his childhood and started working on the war. While he was alive of course I always had the gold mine of his memory, and the opportunity to call him up and ask him questions: “What was the weather like on this day and what kind of jacket were you wearing back then?”

S: And he remembered?!!?

E: Yes, because he was an elephant! He was incredible. Maybe, at the origin of this project, there is the decision to pay a tribute to his incredible memory, because most people are not able to answer questions about the days of their lives. After his death, I decided that was the moment for me to travel to find his traces, to follow in his footsteps and meet some people who had known him. So I went to America and to Germany, which he had occupied with Patton’s army. It turned into an inquiry. I sent shot-in-the-dark letters to people wherever and got answers or not. In 2009 I was in Ohio with an old flame of his, his girlfriend when he was 20 and she was 16. Almost every week, even now, I receive photographs from a historian in the Czech Republic, who read the book when it was translated into the Czech language. (Alan’s War has by now been translated into ten languages.) The mission that took Alan from Germany to Czechoslovakia during the war is not well documented, but it is the specialty of this historian. I went to visit him and he opened his archives to me. He wanted to help me (even though of course the war is over for me now!) to find Alan, and the fact is that we didn’t when I was with him. We found pictures of people in the book: I recognized the top sergeant, and others. But it was only a few months later, after I came home, that I received from him a picture of Alan himself.

I meet people here and there who are often moved and interested by the fact that a young person is dedicating an important part of his life to an older one. That always attracts attention because we carry within us an urge to listen to those who have more experience. A lot of doors opened to help, to provide clues and images and memories, so the fact is that this project becomes more and more interesting as time passes.

S: Since you brought up photographs: Alan talked to you for a long time but he also gave you pictures from his past. What’s the relationship between images and words in this project? How do these photos function as memory tools within the context of the books?

E: Some of them are published in the books, or interpreted, re-drawn to be presented in the books…

S: And how do you make those decisions?

E: I wanted the reader to see his face, his actual face in a photograph, at least once in the book. In the American edition, I included a photo album at the end of the book since I know Americans have all seen and owned pictures like these. But in the rest of the book there are no actual photos because the drawings refuse to be associated with them. I tried, but it doesn’t work. You have to have a graphic style that is very particular to allow a drawing to be near a photographic image: most of the time they don’t want to be side by side and they fight against each other until one of the two is dead.

S: But you know that Barthes called photographs “counter-memories.” He insisted that they stop the process of memory. As an artist, you are trying to delve into the process of memory, so these two types of images are fighting against each other not only visually but also philosophically.

E: Exactly, but the fact is that these photographs are not part of my memory. They are part of his. If you accept the fact that now I’ve been living with them for almost twenty years, you realize that they have now become part of my life too. This also is something very interesting, and it is something that I will have to explore in later years. The time has not yet come, since I am still the process of treating his testimony. I have told the story of his war and his childhood, but his teenage years are still to come. Until that is done, I’m not thinking too much about everything that is happening to ME by working so long on such a subject. After I have finished telling his story, that will be the moment to ask myself “what have I done, and why?” And when that happens I will be probably be about the age he was when I met him!

S: Yo!

E: But about the pictures: I have a few anecdotes to tell. For instance, I would go to California with Alan’s photo album in hand. In this album, there is a picture of a house on a certain street. I knew he lived in this house, I knew more or less when, but I didn’t have the number of the street address – and you know streets in California can go on from San Francisco to San Diego! So I would spend days going up and down a street looking for this house. I knew that I might not find it. There was always the risk that the building would be gone, or changed, or that trees might have grown. But I do this only for the emotion I have when (if!) I do find it. If I do find the house, that’s fabulous, and I just sit in front of it staring in amazement…

S: Have you ever gone in to meet the people who live there now?

E: No, I haven’t done that yet, because I haven’t yet drawn these houses in the books. When I do, the books are going to come back to these places in California. They will be in libraries and bookstores, there will be blogs and people in the neighborhoods will know.

S: And then the people living in the houses now will invite you to tea!

E: Yes, maybe, and then that invitation will become part of the story too. It’s like the chance meeting I had with Alan on the streets of the Ile de Ré. I prefer to wait and let things happen. Sometimes when I do find people and see places, it is precious for me because I can draw exactly what is there, and often people have closets full of documentation that they generously offer to share with me. And the story grows.

The book I have just finished, of course, is about Alan’s early years. The war book was about the experiences of a soldier who never really faced fire, who traveled through Europe seeing countries and meeting people. Alan’s Childhood, on the other hand, is about everyday, simple anecdotes, his family and the people in his young life: his uncles, grandparents, friends, his drawings etc.

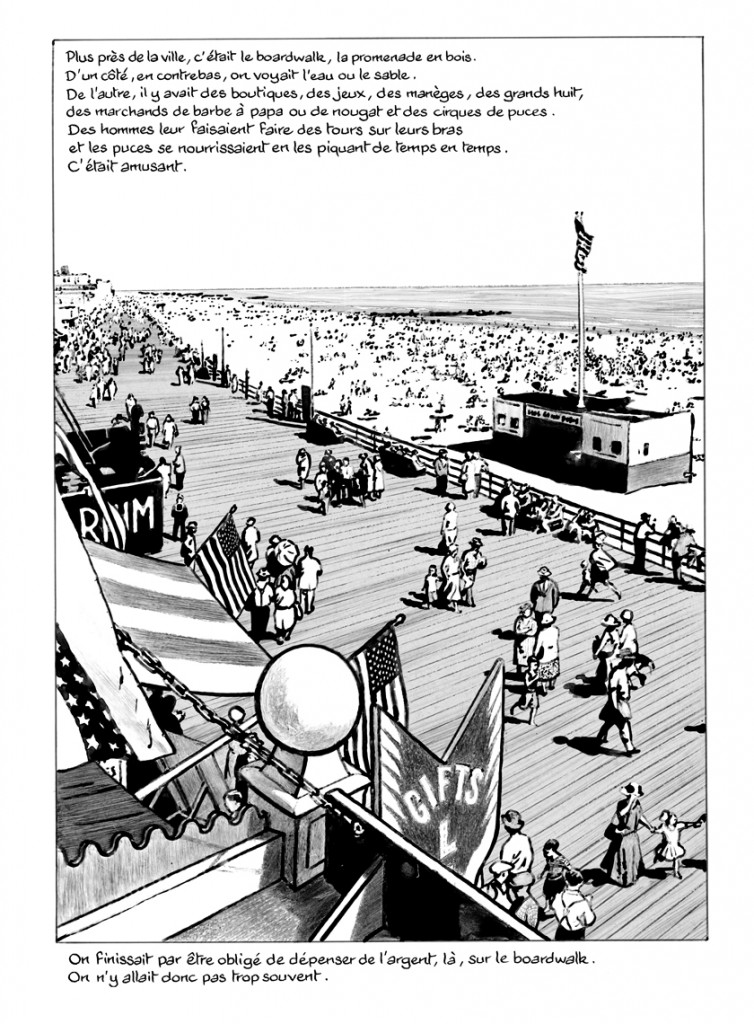

S: I have the sense that this new book is very much a look at la vie quotidienne of a young person living in California at that time.

E: Yes, but Alan’s childhood coincided with the Great Depression since he born in 1925. His father lost his job, his grandparents moved in with them because they couldn’t afford a home, there were earthquakes…

S: So there were natural disasters and human made disasters…

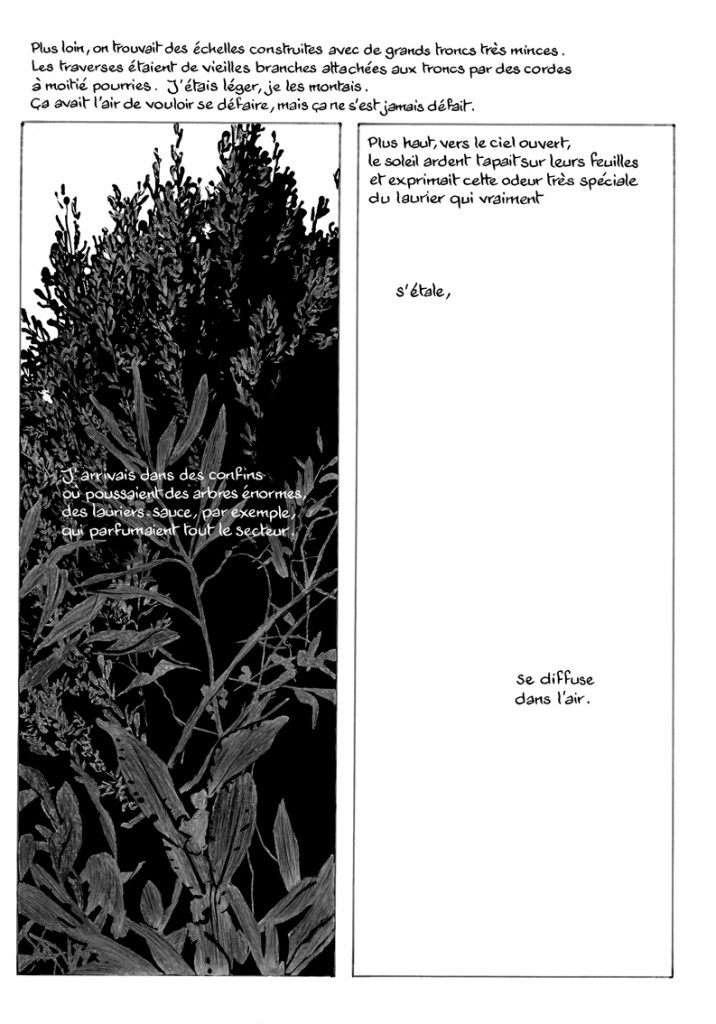

E: Yes, all mixed up with the simplest things of childhood. One thing I have learned from listening to older people, is that even though a person may have lived very dramatic moments in his adult life, the things that stay closest to the bones are the facts of childhood. What remains in a lifetime are the first memories from which all the others grow, early memories that Alan sometimes told me with a trembling voice – a voice never present when he talked about the war or other aspects of his later life, some of them very dramatic. I try to capture that intensity in the new book. I tell my readers simple stories, many of which they have already lived themselves. But when your work is very simple it is also very risky, because the frontier between art and the banal is very, very thin. But that is where I like to be: some place we have all experienced.

Alan had a particular gift for telling those stories, which is part of my admiration for him. When I was with him, sometimes I would have this hallucination that he was shining with the capacity to resurrect episodes so one could SEE what he was saying. But when you see what someone says, you build the picture only from your patrimony. The images you are able to put together to illustrate what someone is telling you are not theirs; they are those that you have created yourself by connecting deeply with another. That is the miracle, that is what I call friendship. I make books to prove that it is possible for one person to listen so carefully to another that there will be coincidences in their visions, because there is in fact a certain logic to life. All of these human experiences, we have them in us, which is the reason why stories can pass from one person to another. They all play on the same keyboard.

© Shelley Rice and Emmanuel Guibert, 2012

Many thanks to Edgar Castillo, for his technical help and support

For all images: © Emmanuel Guibert & L’Association, 2012