George Dureau: Black

on view at Higher Pictures Gallery, New York City, May 31-July 13, 2012

In 1978, Marcuse Pfeifer organized an exhibition in her uptown New York City gallery entitled The Male Nude: A Survey in Photography. Hung salon style, overflowing from floor to ceiling with images by Imogen Cunningham, George Platt Lynes, F.H. Day, Baron von Gloeden, Minor White and many others that had been hidden “in the closet,” the show blew the lid off of American homophobia at around the same time that the Robert Samuel Gallery, devoted to a gay clientele and its interests, opened downtown. I wrote the introduction to the exhibition catalog, and because of this involvement I was privileged to spend months discovering both the hidden archive and the issues – formal, political, conceptual, aesthetic – it articulated.

The young Robert Mapplethorpe was included in The Male Nude show – it was one of his early exhibits. This was the first glimpse I had of him, and it was around the same time that I saw works by artists like Joel-Peter Witkin, Lynn Davis and George Dureau. Davis and Dureau were big influences on Mapplethorpe, whose subsequent notoriety and success have obscured the very real context from which his pictures grew. As the press release of Black, a small but stunning exhibition of black and white photographs by Dureau from 1973-1986, makes clear, the two men were friends in the early 1970s. Born in New Orleans in 1930 (where he still lives at age 81), Dureau was already known as a painter by the time he met the young photographer; he had originally picked up the camera as an extension of his primary expressive medium, but his powerful pictures soon developed a life and a following of their own. One of his admirers was Robert Mapplethorpe, and a comparison of their works is useful for understanding not only the similarities and differences of their oeuvres but also the language of the body that was current during this breakthrough historical moment.

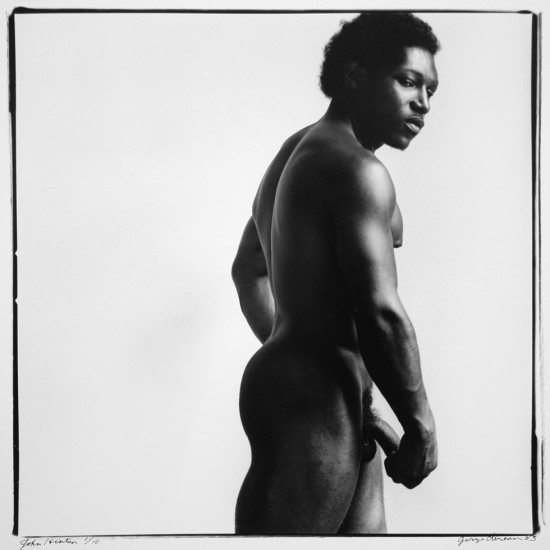

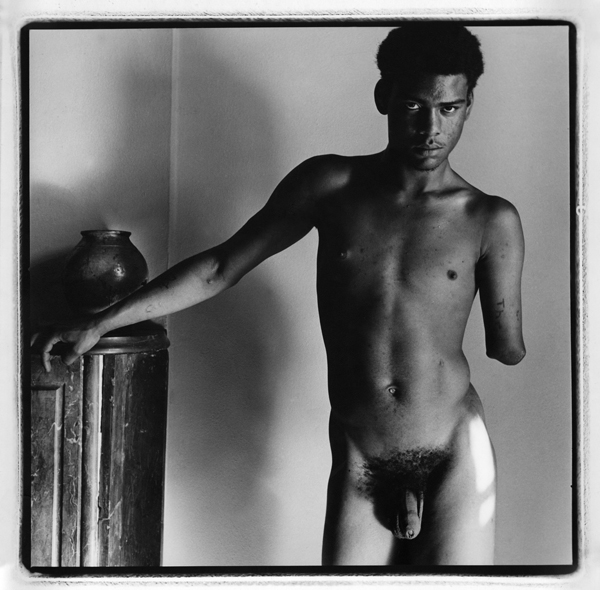

Both of these men were attracted to the black body, and the exhibition focuses mainly on this aspect of Dureau’s work. And both were obsessed with the relationship between timeless, classical beauty and the documentary particularities of photography – a relationship that also was central to the photographic aesthetics of Walker Evans, Lisette Model, Aaron Siskind and others working around this time. For Mapplethorpe, these poles were perceived through the lens of Edward Weston. Transformed into “quintessential” forms, decontextualized and monumentalized, Weston’s sitters morphed into absolutes, into formal essences that linked their limbs to the “universal rhythms” of nature, technology and the clouds. Sensual rather than sexual, focused most often on the female rather than the male body, Weston’s example provided the hurdle over which the militantly gay Mapplethorpe could jump. Stark, sexual, filled with the promise of power, his sitters wrested themselves from the natural continuum of time and space to become iconic containers of male desire, abstractions both stylized and impersonal. Real people, frozen by the camera’s click, retreated into a cool classicism implied not only by their physical perfection but also by their transcendence of particularity.

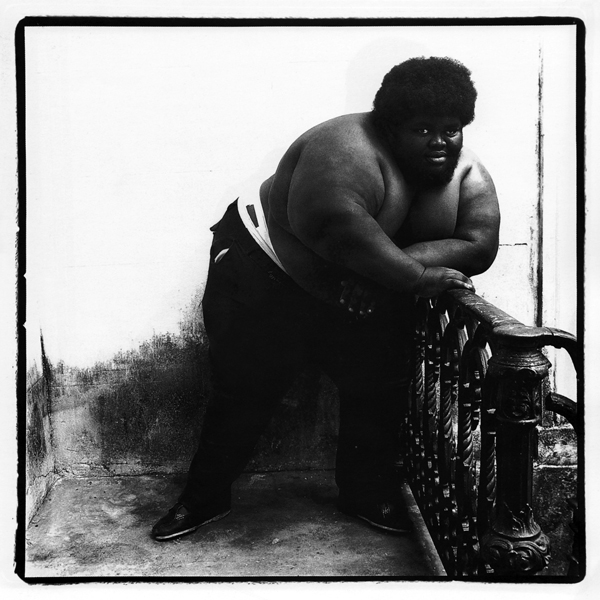

Dureau, on the other hand, was a people person, not an aesthete like either Mapplethorpe or Weston. His pictures breathe, they pulse, they are hot with the blood and sweat of the sitters who joined him in his apartment on Esplanade Street in the city where he was born, and sometimes posed with props that were part of his personal effects. Edward Lucie-Smith, who wrote a fine introduction to a book of Dureau’s photographs published in the 1980s, compared the artist’s ability to transform these autobiographical encounters into photographically classical pictures with the writing strategies of Baudelaire, most notably in the Tableaux Parisiens of Les Fleurs du Mal. Like the poet, Dureau sought out the seamy underbelly of city life, and stared at its personification through the lens of a Hasselblad camera. His subjects are often street people, dressed or nude friends, handicapped or deformed men who might inhabit the dark side of the New Orleans scene. Whereas Baudelaire could take a poor girl, a bum, an old woman or a melancholy clown and transform these figures into archetypes of the forsaken, elevating them to myth through the language of lyric poetry, Dureau’s eye stared so lovingly, with so much intimacy, respect, empathy and desire, at the people – white or black, fat or thin, beautiful or deformed – who inhabited his daily landscape that their portraits now glow with what James Agee once called “the cruel radiance of what is.” All of the intensity of psychological and emotional experience – not abstract or mythic truth but subjective, personal, particular truth – pours into the timeless formality of these poses, to spectacular effect.

Higher Pictures’ press release points out that this is the first New York solo exhibition of this extraordinary body of work by this extraordinary artist. What on earth have we been waiting for?

SR

© Shelley Rice, 2012