Alexander Gray Associates

April 11- May 25, 2012

Lorraine O'Grady "The Fir-Palm", 1991/2012, Silver gelatin print (Photomontage) Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, NY

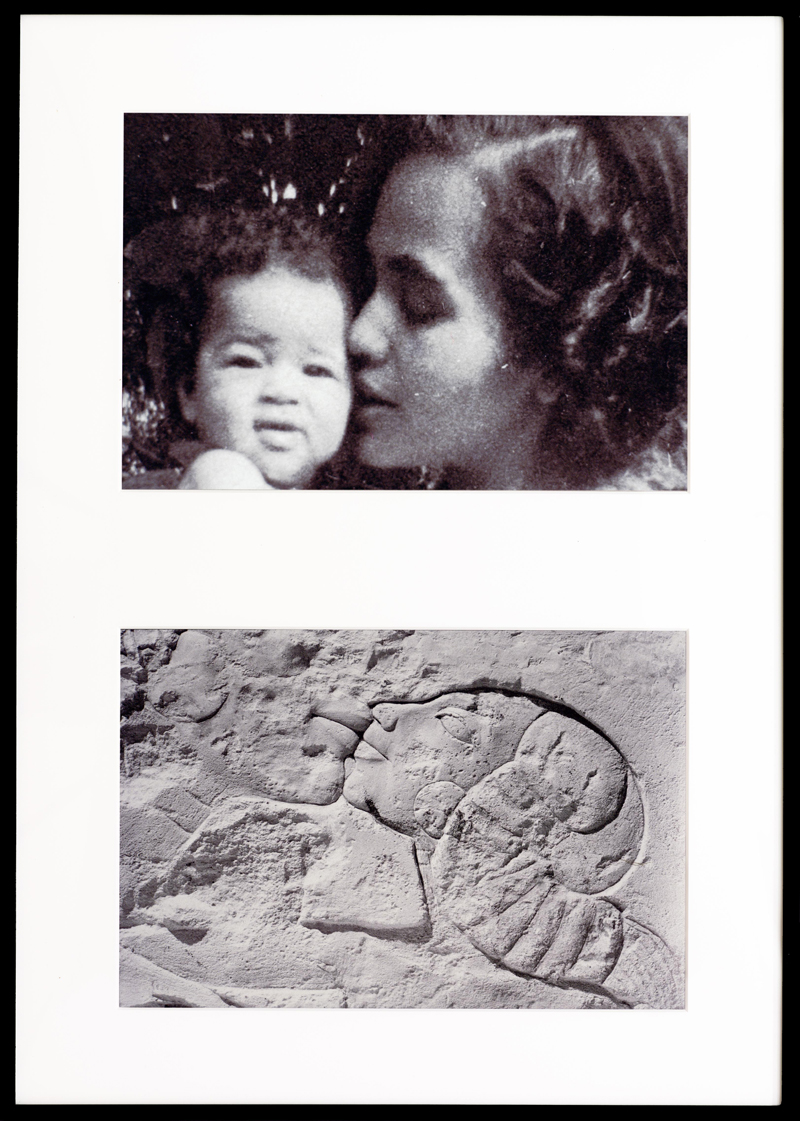

Lorraine O’Grady has been around a long time. An active and avid feminist, a conceptual artist, photographer, writer, performer and video artist, she has been at the forefront of discussions about African Americans and their relationships to the multiple pasts of our complex postcolonial society. I first came across her art in New York around 1980, when she pioneered ideas that would resonate with the groundbreaking works of women like Adrian Piper and, later, Carrie Mae Weems, Deb Willis and Lorna Simpson. Juxtaposing two black and white images, the faces of contemporary African American acquaintances next to reproductions of sculptural portraits carved in ancient Egypt, she put forth the evidence of genealogy. Like writer Martin Bernal, the author of the book Black Athena, O’Grady claimed the African heritage of that shining civilization, a pedigree written into the genetic traces of her race and made visible centuries later by the medium of photography.

This was startling work thirty years ago, and though her latest Chelsea gallery show is quite different, it is still deeply rooted in the experience of the Black female body. The Body/Ground series of photomontages, conceived in 1991 and re-formatted for this exhibition in 2012, uses that body to describe, confront and interrogate the condition of the Western landscape. Born in Boston to Jamaican parents, O’Grady was one of the first artists, along with Ana Mendieta, to articulate the complicated conditions of cultural stability, hybridity and displacement experienced by those who take root in a land not their own. The colonized body, for instance, is the “ground” out of which The Fir-Palm tree (an odd cross between a New England fir and Caribbean palm tree) grows upward against a cloudy sky. “My attitude about hybridity,” the artist has said, “is that it is essential to understanding what is happening here. People’s reluctance to acknowledge it is part of the problem… I’m really advocating for the kind of miscegenated thinking that’s needed to deal with what we’ve already created here.” The landscape which all of us inhabit today is, from her point of view, the amalgamation of the colonized body and the soil to which it has been transplanted.

Lorraine O'Grady "Miscegenated Family Album (A Mother's Kiss)", T: Candace and Devonia; B: Nefertiti and daughter, 1980/1994, Cibachrome Prints, Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, NY

Landscape (Western Hemisphere) is, in fact, the title of her most recent work, an 18-minute video that once again weaves nature and culture, Africa and the West, into an inextricable web. It is a web, of course, grown from the Black body but inscribed and circumscribed, exoticized and eroticized, by the Others. The dark video resembles a dense forest, a thick underbrush blowing in the wind, accompanied by the chirping of birds and jungle sounds. The luxurious, curvaceous foliage fills the screen, blocking our vision. For almost twenty minutes the camera doesn’t move, the viewpoint is stationery and immobilized, action is described only through the vagaries of sound. The rustle of the winds might turn into a howl; the chatter of the forest grows louder or softer, excited or serene as one stares into what seems like mysterious and impermeable darkness. It takes a long time to realize that the dense undergrowth bending and waving in the wind is, in fact, the artist’s own curly hair.

Lorraine O'Grady "Landscape (Western Hemisphere)", 2011, vidéo 19 Minutes, Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, NY

The preoccupation with kinky hair is, of course, well known in African-American circles, and has been a fertile theme for contemporary artists as diverse as Betty Saar and the comedian Chris Rock. Straight or curly? For artists concerned with identity politics, the question is hardly naïve. It has instead become the nexus point, indeed the battle ground, for opposing definitions of physical beauty: the choice is between “going natural” or to succumbing to the standards set by the genetic endowments of white Americans. But of course this is not simply a question of style, since the “natural” black woman’s hair – like her body – was constructed by colonialists as the site of the primal, the untamed, the erotic energies of the race. For Baudelaire, for instance, his mulatto mistress’s hair was “the oasis where I dream, the gourd from which I gulp the wine of memory,” a memory as wild as it was exotic:

For torpid Asia, torrid Africa

-the wilderness I thought a world away-

survive at the heart of this dark continent…

As other souls set sail to music, mine,

O my love! Embarks on your redolent hair.

Charles Baudelaire, The Head of Hair, from The Flowers of Evil

Trans. Richard Howard

Under these circumstances, of course, O’Grady’s identification of her own head, not only with the “dark continent” described by Baudelaire “a world away” but also with the landscapes of the West, becomes charged with both ironies and deep-seated cultural truths that implicate all of us living in the postcolonial environment. As Baudelaire discovered, intimacy and distance have become inseparable. For three decades, the most personal details have morphed to embody and embrace the most political realities in Lorraine O’Grady’s art. She has carved out her own hybrid territory in this Western hemisphere inhabited by strangers who have become neighbors, and who together need to recognize “what we’ve already created here.”

SR

© Shelley Rice, 2012